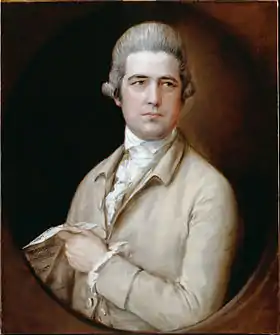

Thomas Linley the younger

Thomas Linley the younger (7 May 1756 – 5 August 1778), also known as Tom Linley, was the eldest son of the composer Thomas Linley the elder and his wife Mary Johnson. He was one of the most precocious composers and performers that have been known in England, and is sometimes referred to as the "English Mozart".[1]

Early life

Outside of London, Bath was the most fashionable city in late 18th century England and, in Bath, the Linleys were the most influential musical family.

Originally from Gloucestershire and of a modest background (Tom's grandfather was a carpenter/builder whose business later flourished thanks to Bath's urban development), the Linleys quickly became the most prominent artists among the community of musicians providing entertainment to the wealthy tenants of the elegant city.[2] Charles Burney famously described them as "a Nest of Nightingales".[3]

Tom's father, Thomas Linley the elder, who worked as a music and singing teacher, took over the management of the musical performances held at the Assembly rooms in Bath in 1766 and then became musical director of the New Bath Assembly Rooms in 1771. He soon put his children, whose musical education he supervised,[4] to work. First, in 1762, Tom and his sister Elizabeth were selling tickets to the concerts and soon after, as early as 1763, they were performing in front of full houses with their other siblings.[5] Anything earned by the children was commandeered by Linley the elder[6] and the talented youngsters quickly became a major source of income[6] allowing the family finances to prosper and raising their social standing.[7]

Tom, whose abilities were apparent from a very young age, played a violin concerto at a concert in Bristol on 29 July 1763 at the age of 7. He started to compose soon after.[2] William Boyce, Master of the King's Musick at the time, took him under his wing. From then on, their father always asking for higher fees for them, Tom and his siblings started to appear further afield, notably in charity concerts and oratorios, including in London. In 1767, Tom appeared at Covent Garden, along with his sister Elizabeth, in Thomas Hull's The Fairy Favour, a masque written for the entertainment of the Prince of Wales, in which Tom sang, danced a hornpipe and played the violin.

Italy

Between 1768 and 1771, Tom journeyed to Italy to study violin and composition with Pietro Nardini in Florence. There he met Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in April 1770 and Charles Burney in September of the same year.[1] In reference to Linley, Burney later wrote, "The Tommasino, as he is called, and the little Mozart, are talked of all over Italy as the most promising geniuses of this age."[3] Tom and Wolfgang, both of them 14 year old teenagers, formed a close friendship making and playing music together, so much so that, as is explained by Robert Gutman, their separation when Mozart left for Rome was a difficult moment for the both of them, with “a melancholy Thomas follow[ing] the Mozarts' coach as they departed […]”[8] They would never meet again.

Work

On his return to England he performed in the concerts directed by his father in Bath and at various oratorios at the Drury Lane, of which he was leader between 1773 and 1778.

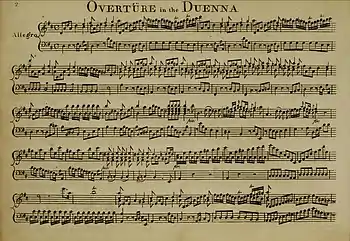

A significant number of Linley's compositions have been lost, including many in the Drury Lane Fire of 1809. Surviving works attest to his congenial mastery of melody, gift for counterpoint, and musical imagination.[1] Linley composed violin sonatas and concertos as well as choral works, and provided most of the music for his brother-in-law Richard Brinsley Sheridan's opera The Duenna (1775). Among his surviving works are Let God Arise a large-scale cantata-anthem for the Three Choirs Festival (1773)[9] an "Ode on the Spirits of Shakespeare", the Lyric Ode (1776), set to a text by his fellow-Bathonian French Laurence, an oratorio entitled The Song of Moses (1777), an afterpiece comic opera (The Cady of Bagdad) and substantial incidental music for Sheridan's 1777 production of The Tempest. Linley also assisted his father, and their works (cantatas, madrigals, glees, elegies and songs) were published together in two volumes.

Death

Tom was a host of the Duke of Ancaster with his sister Mary and "his Companion Mr. Olivarez, Italian Master" – maybe the Spanish violin virtuoso and composer Juan Oliver y Astorga – at Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire, when he drowned in a boating accident "just three months after his 22nd birthday".[10]

On Saturday, 15 August 1778, the Oxford Journal reported the circumstances of his death as follows:[11]

On Wedneſday the 5th Inſtant, Mr. Thomas Linley, eldeſt Son of Mr. Linley, one of the Proprietors of Drury-lane Theatre, fell out of a Boat into a Lake belonging to his Grace the Duke Ancaſter, at Grimſthorpe in Lincolnſhire, and was unfortunately drowned. The Circumſtances of his Death are thus related by a Perſon just arrived from Grimſthorpe: Mr. Linley and Mr. Olivarez, Italian Maſter, and another Perſon, agreed to go on the Lake in a Sailing Boat, which Mr. Linley ſaid he could manage; but no ſooner had they ſailed into the Middle of the Lake, than a ſudden Gale of Wind ſprang up, and overſet the Boat; however, they all hung by the Maſt and Rigging for ſome Time, till Mr. Linley ſaid he found it was in vain to wait for Aſsiſtance, and therefore, though he had his Boots and Great Coat on, was determined to ſwim to Shore, for which Purpoſe he quitted his Hold, but had not ſwam above a hundred Yards before he ſunk. Her Grace the Ducheſs of Ancaſter ſaw the whole from her Dreſsing-room Window, and immediately ordered ſeveral Servants to take another Boat, and go to their Aſsiſtance, but they unfortunately only came early enough to take up Mr. Olivarez, his Companion, not being able to find the Body of Mr. Linley for more than forty Minutes.— Miſs M. Linley came up to Town with the melancholy Tidings of the Diſaster, and now lies dangerously ill at the Duke of Ancaſter's in Berkeley-ſquare; Mrs Sheridan is likewiſe inconfortable [sic.] for the Loſs of ſo valuable a Brother; and Yeſterday Mr. Linley his father whoſe Sufferings on the Occaſion no Language can expreſs, went down to pay the laſt Tribute to a beloved Son.

Tom's funeral was held at Edenham parish church but parish records indicate that he was not buried there (local rumour has it that his body was taken to Bath to be interred). Linley's early death was immediately recognised as a tragedy for English music.

In his memoirs the Irish tenor Michael Kelly remembers how, in about 1786 after a concert in Vienna, he happened to be sitting at supper between Mozart and Constance Weber, and how Mozart, to whom he was being introduced for the first time, "conversed with [him] a good deal about Thomas Linley ... with whom he was intimate at Florence, and [how Mozart] spoke of him with great affection... [saying] that Linley was a true genius; and [that] he felt that, had he lived, he would have been one of the greatest ornaments of the musical world."[12]

Discography

Despite its remarkable quality and idiosyncrasies, the music of Tom Linley is not widely known. There are however a few commercial recordings in existence, most of them published by the independent British classical label Hyperion and its subsidiary label Helios.

- A Lyric Ode on the Fairies, Aerial Beings and Witches of Shakespeare, The Parley of Instruments, Paul Nicholson (Helios, CDA66613, 2005)

- Cantatas & Theatre Music (Music for The Tempest, Overture to The Duenna and the three cantatas: In Yonder Grove, Ye Nymphs of Albion's beauty-blooming isle and Daughter of Heav'n fair art though) Julia Gooding, The Parley of Instruments, Paul Nicholson (Helios, CDA66767, 2006)

- The Song of Moses & Let God arise, The Parley of Instruments, Peter Holman (Helios, CDA67038, 2008)

- The song "To heal the wound a bee had made" is available on Enchanting Harmonist – A soirée with the Linleys of Bath, Rufus Müller, Invocation (Hyperion, CDA66698, 1993)

- A Violin Sonata in A major is available on English 18th-century Violin Sonatas, The Locatelli Trio (Hyperion, CDA66583, 1992)

- His only surviving violin concerto (Violin Concerto in F major) is available on English Classical Violin Concertos, Elizabeth Wallfisch, The Parley of Instruments, Peter Holman (Helios, CDH55260, 2008)

On the label Philips Classics:

- A Shakespeare Ode on the Witches and Fairies, Musicians of the Globe, Philip Pickett (Philips Classics, 446-689-2, 1998)

On the label Oehms Classics,

- Another recording of Linley's only surviving violin concerto (Violin Concerto in F major) is available on Mozart in Italien, Mirjam Contzen, Bayerische Kammerphilharmonie, Reinhard Goebel (Oehms Classics, OC 753, 2010)

See also

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Gwilym Beechey; Linda Troost (2001). "Linley family". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.16713. (subscription required)

- Holman, Peter (1996). English Classical Violin Concertos. London: Hyperion Records. p. 2. CDA66865.

- Charles Burney: An Eighteenth-century Musical Tour in France and Italy, p. 184; ed. by P. A. Scholes; Oxford University Press, 1959

- Chedzoy (1998), p. 10.

- Chedzoy (1998), p. 7.

- Black (1911), p. 21.

- Chedzoy (1998), p. 17.

- Gutman, Robert (1999). Mozart: A Cultural Biography. San Diego, USA: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-601171-9.

- "Thomas Linley". www.music18.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- "Thomas Linley: how the 'English Mozart' died aged 22 in a boating tragedy". BBC Music Magazine. 15 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Oxford Journal – Saturday 15 August 1778 – Thursday's Post. from The London Gazette. Dresden, July 19". The Oxford Journal. 1778.(subscription required)

- Kelly, Michael. Reminiscences of Michael Kelly of the King's Theatre and Theatre Royal Drury Lane, Including a Period of Nearly Half a Century with Original Anecdotes of Many Distinguished Persons, Political, Literary, and Musical, Volume 1. London: Henry Colburn, New Burlington Street (1826). p. 222.

Sources

- Black, Clementina (1911). The Linleys of Bath. Martin Secker.

- Chedzoy, Alan (1998). Sheridan's Nightingale. Allison & Busby. ISBN 0-7490-0341-3.