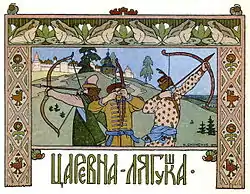

The Frog Princess

The Frog Princess is a fairy tale that has multiple versions with various origins. It is classified as type 402, the animal bride, in the Aarne–Thompson index.[1] Another tale of this type is Doll i' the Grass.[2]

Russian variants include the Frog Princess or Tsarevna Frog (Царевна Лягушка, Tsarevna Lyagushka)[3] and also Vasilisa the Wise (Василиса Премудрая, Vasilisa Premudraya); Alexander Afanasyev collected variants in his Narodnye russkie skazki.

Synopsis

The king (or an old peasant woman, in Lang's version) wants his three sons to marry. To accomplish this, he creates a test to help them find brides. The king tells each prince to shoot an arrow. According to the King's rules, each prince will find his bride where the arrow lands. The youngest son's arrow is picked up by a frog. The king assigns his three prospective daughters-in-law various tasks, such as spinning cloth and baking bread. In every task, the frog far outperforms the two other lazy brides-to-be. In some versions, the frog uses magic to accomplish the tasks, and though the other brides attempt to emulate the frog, they cannot perform the magic. Still, the young prince is ashamed of his frog bride until she is magically transformed into a human princess.

In Calvino's version, the princes use slings rather than bows and arrows. In the Greek version, the princes set out to find their brides one by one; the older two are already married by the time the youngest prince starts his quest. Another variation involves the sons chopping down trees and heading in the direction pointed by them in order to find their brides.[4]

In the Russian versions of the story, Prince Ivan and his two older brothers shoot arrows in different directions to find brides. The other brothers' arrows land in the houses of the daughters of an aristocrat and a wealthy merchant, respectively. Ivan's arrow lands in the mouth of a frog in a swamp, who turns into a princess at night. The Frog Princess, named Vasilisa the Wise, is a beautiful, intelligent, friendly, skilled young woman, who was forced to spend 3 years in a frog's skin for disobeying Koschei. Her final test may be to dance at the king's banquet. The Frog Princess sheds her skin, and the prince then burns it, to her dismay. Had the prince been patient, the Frog Princess would have been freed but instead he loses her. He then sets out to find her again and meets with Baba Yaga, whom he impresses with his spirit, asking why she has not offered him hospitality. She tells him that Koschei is holding his bride captive and explains how to find the magic needle needed to rescue his bride. In another version, the prince's bride flies into Baba Yaga's hut as a bird. The prince catches her, she turns into a lizard, and he cannot hold on. Baba Yaga rebukes him and sends him to her sister, where he fails again. However, when he is sent to the third sister, he catches her and no transformations can break her free again.

In some versions of the story, the Frog Princess' transformation is a reward for her good nature. In one version, she is transformed by witches for their amusement. In yet another version, she is revealed to have been an enchanted princess all along.

Analysis

Tale type

Russian researcher Varvara Dobrovolskaya stated that type SUS 402, "Frog Tsarevna", figures among some of the popular tales of enchanted spouses in the Russian tale corpus.[5] In some Russian variants, as soon as the hero burns the skin of his wife, the Frog Tsarevna, she says she must depart to Koschei's realm,[6] prompting a quest for her (tale type ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife").[7] Jack Haney stated that the combination of types 402, "Animal Bride", and 400, "Quest for the Lost Wife", is a common combination in Russian tales.[8]

Researcher Carole G. Silver states that, apart from bird and fish maidens, the animal bride appears as a frog in Burma, Russia, Austria and Italy; a dog in India and in North America, and a mouse in Sri Lanka.[9]

Professor Anna Angelopoulos noted that the animal wife in the Eastern Mediterranean is a turtle, which is the same animal of Greek variants.[10] In the same vein, Greek scholar Megas noted that similar aquatic beings (seals, sea urchin) and water-related entities (gorgonas, nymphs, neraidas) appear in the Greek oikotype of type 402.[11]

Yolando Pino-Saavedra located the frog, the toad and the monkey as animal brides in variants from the Iberian Peninsula, and from Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking areas in the Americas.[12]

Role of the animal bride

The tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 402, "The Animal Bride". According to Andreas John, this tale type is considered to be a "male-centered" narrative. However, in East Slavic variants, the Frog Maiden assumes more of a protagonistic role along with her intended.[13] Likewise, scholar Maria Tatar describes the frog heroine as "resourceful, enterprising, and accomplished", whose amphibian skin is burned by her husband, and she has to depart to regions unknown. The story, then, delves into the husband's efforts to find his wife, ending with a happy reunion for the couple.[14]

On the other hand, Barbara Fass Leavy draws attention to the role of the frog wife in female tasks, like cooking and weaving. It is her exceptional domestic skills that impress her father-in-law and ensure her husband inherits the kingdom.[15]

Maxim Fomin sees "intricate meanings" in the objects the frog wife produces at her husband's request (a loaf of bread decorated with images of his father's realm; the carpet depicting the whole kingdom), which Fomin associated with "regal semantics".[16]

A totemic figure?

Analysing Armenian variants of the tale type where the frog appears as the bride, Armenian scholarship suggests that the frog bride is a totemic figure, and represents a magical disguise of mermaids and magical beings connected to rain and humidity.[17]

Likewise, Russian scholarship (e.g., Vladimir Propp and Yeleazar Meletinsky) has argued for the totemic character of the frog princess.[18] Propp, for instance, described her dance at the court as some sort of "ritual dance": she waves her arms and forests and lakes appear, and flocks of birds fly about.[19] Charles Fillingham Coxwell also associated these human-animal marriages to totem ancestry, and cited the Russian tale as one example of such.[20]

In his work about animal symbolism in Slavic culture, Russian philologist Aleksandr V. Gura stated that the frog and the toad are linked to female attributes, like magic and wisdom.[21] In addition, according to ethnologist Ljubinko Radenkovich, the frog and the toad represent liminal creatures that live between land and water realms, and are considered to be imbued with (often negative) magical properties in Slavic folklore.[22] In some variants, the Frog Princess is the daughter of Koschei, the Deathless,[23] and Baba Yaga - sorcerous characters with immense magical power who appear in Slavic folklore in adversarial position. This familial connection, then, seems to reinforce the magical, supernatural origin of the Frog Princess.[24]

Other motifs

Georgios A. Megas noted two distinctive introductory episodes: the shooting of arrows appears in Greek, Slavic, Turkish, Finnish, Arabic and Indian variants, while following the feathers is a Western European occurrence.[25]

Variants

Andrew Lang included an Italian variant of the tale, titled The Frog in The Violet Fairy Book.[26] Italo Calvino included another Italian variant from Piedmont, The Prince Who Married a Frog, in Italian Folktales,[27] where he noted that the tale was common throughout Europe.[28] Georgios A. Megas included a Greek variant, The Enchanted Lake, in Folktales of Greece.[29]

This tale is closely related to Puddocky and its variants, in which a king sets three tasks to his sons to determine which is best suited to rule the country, and a transformed frog helps the youngest prince.

In a Czech variant translated by Jeremiah Curtin, The Mouse-Hole, and the Underground Kingdom, prince Yarmil and his brothers are to seek wives and bring to the king their presents in a year and a day. Yarmil and his brothers shoot arrow to decide their fates, Yarmil's falls into a mouse-hole. The prince enters the mouse hole, finds a splendid castle and an ugly toad he must bathe for a year and a day. When the date is through, he returns to his father with the toad's magnificent present: a casket with a small mirror inside. This repeats two more times: on the second year, Yarmil brings the princess's portrait and on the third year the princess herself. She reveals she was the toad, changed into amphibian form by an evil wizard, and that Yarmil helped her break this curse, on the condition that he must never reveal her cursed state to anyone, specially to his mother. He breaks this prohibition one night and she disappears. Yarmil, then, goes on a quest for her all the way to the glass mountain (tale type ATU 400, "The Quest for the Lost Wife").[30]

In a Ukrainian variant collected by M. Dragomanov, titled "Жена-жаба" ("The Frog Wife" or "The Frog Woman"), a king shoots three bullets to three different locations, the youngest son follows and finds a frog. He marries it and discovers it is a beautiful princess. After he burns the frog skin, she disappears, and the prince must seek her.[31]

In another Ukrainian variant, the Frog Princess is a maiden named Maria, daughter of the Sea Tsar and cursed into frog form. The tale begins much the same: the three arrows, the marriage between human prince and frog and the three tasks. When the human tsar announces a grand ball to which his sons and his wives are invited, Maria takes off her frog skin to appear as human. While she is in the tsar's ballroom, her husband hurries back home and burns the frog skin. When she comes home, she reveals the prince her cursed state would soon be over, says he needs to find Baba Yaga in a remote kingdom, and vanishes from sight in the form of a cuckoo. The tale continues as tale type ATU 313, "The Magical Flight", like the Russian tale of The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise.[32]

Researchers Nora Marks Dauenhauer and Richard L. Dauenhauer found a variant titled Yuwaan Gagéets, heard during Nora's childhood from a Tlingit storyteller. They identified the tale as belonging to the tale type ATU 402 (and a second part as ATU 400, "The Quest for the Lost Wife") and noted its resemblance to the Russian story, trying to trace its appearance in the teller's repertoire.[33]

In a variant from northern Moldavia collected and published by Romanian author Elena Niculiță-Voronca, the bride selection contest replaces the feather and arrow for shooting bullets, and the frog bride commands the elements (the wind, the rain and the frost) to fulfill the three bridal tasks.[34]

Adaptations

- A literary treatment of the tale was published as The Wise Princess (A Russian Tale) in The Blue Rose Fairy Book (1911), by Maurice Baring.[35]

- A translation of the story by illustrator Katherine Pyle was published with the title The Frog Princess (A Russian Story).[36]

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1939 Soviet film directed by Aleksandr Rou, is based on this plot. It was the first large-budget feature in the Soviet Union to use fantasy elements, as opposed to the realistic style long favored politically.[37]

- In 1953 the director Mikhail Tsekhanovsky had the idea of animating this popular national fairy tale. Production took two years, and the premiere took place in December, 1954. At present the film is included in the gold classics of "Soyuzmultfilm".

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1977 Soviet animated film is also based on this fairy tale.

- In 1996, an animated Russian version based on an in-depth version of the tale in the film "Classic Fairy Tales From Around the World" on VHS. This version tells of how the beautiful Princess Vasilisa was kidnapped and cursed by the evil wizard Kashay to make her his bride and only the love of the handsome Prince Ivan can free her.

- Taking inspiration from the Russian story, Vasilisa appears to assist Hellboy against Koschei in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls.

- The Frog Princess was featured in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, where it was depicted in a country setting. The episode features the voice talents of Jasmine Guy as Frog Princess Lylah, Greg Kinnear as Prince Gavin, Wallace Langham as Prince Bobby, Mary Gross as Elise, and Beau Bridges as King Big Daddy.

- A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék ("Hungarian Folk Tales") (hu), with the title Marci és az elátkozott királylány ("Martin and the Cursed Princess").

Culture

Music

The Divine Comedy's 1997 single The Frog Princess is loosely based on the theme of the original Frog Princess story, interwoven with the narrator's personal experiences.

References

- Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 224, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- D. L. Ashliman, "Animal Brides: folktales of Aarne–Thompson type 402 and related stories"

-

Works related to The Frog-Tzarevna at Wikisource

Works related to The Frog-Tzarevna at Wikisource - Out of the Everywhere: New Tales for Canada, Jan Andrews

- Dobrovolskaya, Varvara. "PLOT No. 425A OF COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS (“CUPID AND PSYCHE”) IN RUSSIAN FOLK-TALE TRADITION". In: Traditional culture. 2017. Vol. 18. № 3 (67). p. 139.

- Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA - Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- Kobayashi, Fumihiko (2007). "The Forbidden Love in Nature. Analysis of the "Animal Wife" Folktale in Terms of Content Level, Structural Level, and Semantic Level". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore. 36: 144–145. doi:10.7592/FEJF2007.36.kobayashi.

- Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 548. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- Silver, Carole G. "Animal Brides and Grooms: Marriage of Person to Animal Motif B600, and Animal Paramour, Motif B610". In: Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (eds.). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. A Handbook. Armonk / London: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. p. 94.

- Angelopoulos, Anna. "La fille de Thalassa". In: ELO N. 11/12 (2005): 17 (footnote nr. 5), 29 (footnote nr. 47). http://hdl.handle.net/10400.1/1607

- Angelopoulou, Anna; Broskou, Aigle. "ΕΠΕΞΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ ΠΑΡΑΜΥΘΙΑΚΩΝ ΤΥΠΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΡΑΛΛΑΓΩΝ AT 300-499". Tome B: AT 400-499. Athens, Greece: ΚΕΝΤΡΟ ΝΕΟΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ Ε.Ι.Ε. 1999. p. 540.

- Pino Saavedra, Yolando. Folktales of Chile. [Chicago:] University of Chicago Press, 1967. p. 258.

- Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, Criticism. Norton Critical Edition. Norton, 1999. p. 31. ISBN 9780393972771

- Leavy, Barbara Fass. In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender. NYU Press, 1994. pp. 204, 207, 212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.9.

- Fomin, Maxim. "The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions". In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 259-268. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- Hayrapetyan Tamar. "Combinaisons archétipales dans les epopees orales et les contes merveilleux armeniens". Traduction par Léon Ketcheyan. In: Revue des etudes Arméniennes tome 39 (2020). pp. 499-500 and footnote nr. 141.

- Fomin, Maxim. "The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions". In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 259 (footnote nr. 9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- Propp, V. Theory and history of folklore. Theory and history of literature v. 5. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. p. 143. ISBN 0-8166-1180-7.

- Coxwell, C. F. Siberian And Other Folk Tales. London: The C. W. Daniel Company, 1925. p. 252.

- Гура, Александр Викторович. "Символика животных в славянской народной традиции" [Animal Symbolism in Slavic folk traditions]. М: Индрик, 1997. pp. 380-382. ISBN 5-85759-056-6.

- Radenkovic, Ljubinko. "Митолошки елементи у словенским народним представама о жаби" [Mythological Elements in Slavic Notions of Frogs]. In: Заједничко у словенском фолклору: зборник радова [Common Elements in Slavic Folklore: Collected Papers, 2012]. Београд: Балканолошки институт САНУ, 2012. pp. 379-397. ISBN 978–86–7179-074–1 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: Invalid ISBN..

- Fomin, Maxim. "The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions". In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 260. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- Kovalchuk Lidia Petrovna (2015). "Comparative research of blends frog-woman and toad-woman in Russian and English folktales". In: Russian Linguistic Bulletin, (3 (3)), 14-15. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/comparative-research-of-blends-frog-woman-and-toad-woman-in-russian-and-english-folktales (дата обращения: 17.11.2021).

- Megas, Geōrgios A. Folktales of Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970. p. 224.

- Andrew Lang, The Violet Fairy Book, "The Frog"

- Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 438 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 718 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 49, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1890. pp. 331–355.

- Драгоманов, М (M. Dragomanov)."Малорусские народные предания и рассказы". 1876. pp. 313-317.

- Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 179-181. ISBN 9781576070635.

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Dauenhauer, Richard L. "Tracking “Yuwaan Gagéets”: A Russian Fairy Tale in Tlingit Oral Tradition". In: Oral Tradition, 13/1 (1998): 58-91.

- Ciubotaru, Silvia. "Elena Niculiţă-Voronca şi basmele fantastice" [Elena Niculiţă-Voronca and the Fantastic Fairy Tales]. In: Anuarul Muzeului Etnografic al Moldovei [The Yearly Review of the Ethnographic Museum of Moldavia] 18/2018. p. 158. ISSN 1583-6819.

- Baring, Maurice. The Blue Rose Fairy Book. New York: Maude, Dodd and Company. 1911. pp. 247-260.

- Pyle, Katherine. Tales of folk and fairies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1919. pp. 137-158.

- James Graham, Baba Yaga in Film[Usurped!]