Slovo Building

Slovo Building (Ukrainian: Будинок «Слово») is a residential multi-story building located in the Shevchenkivskyi District of Kharkiv. The shape of the building reflects the letter C in the Ukrainian word слово ("slovo") which means "word". Therefore, the shape of the building symbolized that it was constructed specially for prominent Ukrainian writers, who lived there in a total of 66 apartments. Built in the late 1920s, it housed many Ukrainian writers and poets, some of whom, known as the Executed Renaissance, were later executed by the Soviet Union in Sandarmokh.

| Slovo Building | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Shevchenkivskyi District, Kharkiv, Ukraine |

| Coordinates | 50°00′42″N 36°14′03″E |

Construction

As Kharkiv was the capital of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 19 December 1919 to 24 June 1934,[1] the town became the center of the Ukrainian economy, causing population growth. The population increased 285,000 in 1920 to 423,000 in 1927, thus making housing shortages one of its main problems.[2] This also affected the literary community, who had come to Kharkiv from Kyiv because of the Ukrainization policy.[3] Writers who couldn't afford the higher housing prices lived in their offices or improvised homes, with some poorly-housed writers storing their manuscripts in a pot to keep mice from nibbling at the paper.[1] One writer who lived in his office was Pavlo Tychyna when he became the chief executive of the Chervony Shliakh magazine in 1923.[4]

So, in the mid-1920s, Ostap Vyshnya, at that time part of a writers' organization called плуг, meaning plow, asked the Soviet government to build an apartment complex that could accommodate the most important Ukrainian intellectuals. The idea was almost immediately approved by the Soviets, who saw it as a means to keep tabs on the Ukrainian intellectuals, who would all be within the same building.[4] The new complex was designed in September 1927 by architect Mytrophan Dashkevych, who designed the building in the shape of the letter C in the Cyrillic alphabet to stand for the first letter of слово, meaning word, and the building was named Слово (Slovo).[5] As the building still lacked funds to complete its construction, Vyshnya went to Moscow in February 1929 and asked Joseph Stalin to fund the construction.[6] Stalin agreed and gave the money the same day (on the condition that the residents paid it back within 15 years).[4] Slovo was completed on 25 December 1929.[7]

The building was built in what was considered a lavish fashion, each apartment having 3 or 5 rooms, quite a luxury in the interwar Soviet Union. The Slovo Building is five stories high, with 66 apartments, made with the best materials available at the time. A solarium and a shower were built on the roof,[2] with a preschool in the basement. At the end of 1929, the residents moved in, though central heating was not installed until after New Year's Day 1930. The residents were called Slovyans.[5] Each apartment was equipped with a bathroom, central heating, and telephones. The artists were also given their own studios.[8] After World War II, an elevator was installed, although it only provided access to the ground and fifth floors.[6]

Executed Renaissance

Through the use of tapping telephone, occupant was spied and being reported to be arrested by their neighbor in the age of Executed Renaissance. Actress Halyna Mnevska was the first to be arrested on 20 January 1931 cause she doesn't want to denounce her husband, Klym Polishchuk who was executed by gunfire in Karelia. She was arrested and sentenced to 5 years imprisonment and would never be allowed to return to Ukraine.[1] The second person who was arrested is Pavlo Khrystiuk on 2 March 1931 and Ivan Bahrianyi on 16 March 1932 cause of his counter-revolutionary movement.[6]

As the years progressed, more and more arrests were made, 1933 having the largest number of arrests. Ukrainian writer, Mykhailo Yalovy was arrested on 12 May 1933 for the accusation of espionage and assassination of Pavel Postyshev and later to be executed on 11 March 1937.[6] The next day after Yalovy's arrest, Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Kulish and Oles' Dosvitniy came together to discuss how they could resolve the situation.[4] At the time of the conversation, Khvylovy returned to his room and shot himself on 13 May 1933,[9] highlighting the despair the occupants of Slovo house felt. Not only were the occupants living under constant threat of arrest or death, they were also living through Holodomor.[4] Holodomor is a Stalin made famine which killed four million Ukrainians, mostly peasants.[10] Serhiy Pylypenko was executed without trial on 23 February 1934. Other than them, there were Les Kurbas, Vyshnya, Kulish and Hryhorii Epik who was arrested and executed in Sandarmorkh. Vyshnya was saved cause he was ill[6] All in all, 40 out of 66 apartments in Slovo house were effected. The number executed was 33, with 5 sentenced to long term imprisonment, one committing suicide and another killed under unclear circumstances. Many were sentenced as spies, terrorists and conspirators against the regime.[4]

In 1934, the capital city of Ukraine were moved from Kharkiv to Kyiv, partly due to Holodomor and repression. Subsequently, the surviving writers were moved to RoLit house based in the new capital. During World War II when the Germans started to bomb Kyiv in 1941, the people said with bitter irony that "One bomb on RoLit is enough, and Ukrainian literature will cease to exist."[11]

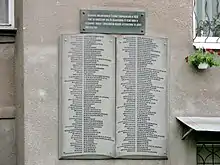

Remembrance

The building was registered in State Register of Immovable Landmarks of Ukraine on 21 August 2019.[12] A memorial plaque which consist the name of famous people who lived in the building was placed on 24 August 2003. The plaque was replacing the old plaque which was already destroyed.[13]

- Jeremiah Eisenstock

- Ivan Bagmut

- Ivan Bahrianyi

- Mykola Bazhan

- Pavlo Baidebura

- Jacob Bash

- Dmitro Bedzyk

- Boris the homeless

- Mykhailo Bykovets

- Sergey Borzenko

- Gennady Brezhnev

- Dmitry Buzko

- Raphael Brusylovsky

- Alexey Petrovich

- Ivan Virhan

- David Vyshnevsky

- Ostap Cherry

- Vasily Vrazhlivy

- Yuriy Vukhnalʹ

- Lev Galkin

- Yukhym Gedz

- Gregory Gelfandbein

- Yuri Gerasimenko

- Vladimir Gzhitsky

- Andriy Golovko

- Ilya Gonimov

- Kost Hordiyenko

- Yaroslav Grimailo

- Oles Gromiv

- Mykola Dashkiev

- Oleksa Desnyak

- Antin Dykyy

- Ivan Dniprovsky

- Mykhailo Dolengo

- Oles Dosvitniy

- Oles Donchenko

- Mykola Dukin

- Hryhorii Epik

- Natalya Zabila

- Mike Johansen

- Ivan Kalyannik

- Jacob Kalnytsky

- Eugene Kasyanenko

- Zelman Katz

- Leib Kvitko

- Іvan Kirilenko

- Pylyp Kozytskiy

- Alexander Kopylenko

- Aaron Kopstein

- Vladimir Koryak

- Hryhoriy Kostyuk

- Boris Kotlyarov

- Gordiy Kotsyuba

- Stepan Kryzhanivsky

- Antin Krushelnytsky

- Ivan Kulyk

- Mykola Kulish

- Oleksa Kundzich

- Les Kurbas

- Ivan Lakiza

- Khan Levin

- Alexander Leites

- Mykola Ledyanko

- Petro Lisovyy

- Arkadiy Lyubchenko

- Іvan Malovichko

- Yakiv Mamontiv

- Teren Masenko

- Varvara Maslyuchenko

- Vadym Meller

- Іvan Miroshnikov

- Ivan Mykytenko

- Igor Muratov

- Mykola Nagnybida

- Halyna Orlivna

- Ivan Padalka

- Andriy Paniv

- Petro Panch

- Leonid Pervomayskiy

- Anatol Petrytsky

- Maria Pylynska

- Sergey Pylypenko

- Valerian Pidmohylny

- Mykhailo Pinchevsky

- Luciana Piontek

- Ivan Plakhtin

- Valerian Polishchuk

- Alexey Poltoratsky

- Andriy Richytsky

- Maria Romanivska

- Vasily Sedlyar

- Mikhail Semenko

- Ivan Senchenko

- Mykola Skazbush

- Oleksa Slisarenko

- Yuriy Smolych

- Heliy Snyehirʹov

- Vasily Sokil

- Volodymyr Sosiura

- Sumnyy Semen Makarovych

- Pavlo Tychyna

- Robert Tretyakov

- Mykola Trublaini

- Natalia Uzhviy

- Pavlo Usenko

- Mykola Fuklev

- Alexander Khazin

- Mykola Khvylovy

- Pavlo Khrystiuk

- Leonid Chernov

- Маrk Chernyakov

- Valentina Chistyakova

- Mykola Shapoval

- Antin Shmygelsky

- Yuri Shovkoplias

- Nikita Shumilo

- Ivan Shutov

- Samylo Shchupak

- Vladimir Yurezansky

- Leonid Yukhvid

- Mykhailo Yalovy

- Yuri Yanovsky

Memorial project

In March 2017, the ProSlovo Project was launched across Ukraine. The research project is dedicated to Slovo House and its past residents. All results, memoirs and images are being published on a web page in interactive form. In English or Ukrainian the audience can observe the timeline of the building, 3D visualization of each apartment, photographs of each resident, maps, and memoirs.[1] During 2017, a documentary film about this building was also released. It was written by Liubov Yakymchuk and Taras Tomenko; it was directed by Tomenko. The film "Slovo House" included a walkthrough of each apartment accompanied by memoirs and eyewitness accounts.[4]

Sources

- http://proslovo.com/kulish-slovoproslovo

- https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Ukraine/Ukraine-Slovo-from-house-of-the-word-to-nightmare-201601

- https://warsawinstitute.org/slovo-house/

- http://euromaidanpress.com/2020/03/12/slovo-house-how-a-special-soviet-apartment-block-for-writers-became-their-prison/

References

- Kiev, Claudia Bettiol (26 May 2020). "Ukraine: Slovo, from "house of the word" to nightmare". balcanicaucaso.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Didenko, Kateryna. "The Slovo Building". constructivism-kharkiv.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Bertelsen, Olga (2013). "The House of Writers in Ukraine, the 1930s: Conceived, Lived, Perceived". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies (2302): 14. doi:10.5195/cbp.2013.170. ISSN 2163-839X. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Bilalov, Rashid; Garrood, Michael, eds. (12 March 2020). "Slovo House — how a special Soviet apartment block for writers became their prison". Euromaidan Press. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "Writer's house "slovo"". ProSlovo. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "Story of Slovo House : From 1923 to nowadays". ProSlovo. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- Bertelsen, Olga (15 February 2016). "Regional Nationalism and Soviet Anxieties during the Great Terror in Ukraine: The Case of Mykhailo Bykovets'". East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 3 (1): 39–74. doi:10.21226/T2H01C. ISSN 2292-7956. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "'Slovo House'". Warsaw Institute. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- Zhadan, Serhiy; Holman, Bob (2019). What We Live For, What We Die For. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-300-22336-1. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- Applebaum, Anne. "Holodomor | Facts, Definition, & Death Toll | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "ProSlovo.com / Володимир Куліш. Слово про слово". ProSlovo (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- Ministry of Culture of Ukraine (21 August 2019). "Кабінет Міністрів України - До Державного реєстру нерухомих пам'яток України внесено 12 об'єктів культурної спадщини національного значення". www.kmu.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "Дом "Слово": историческая память без речей и оваций". www.mediaport.ua (in Ukrainian). 26 August 2003. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

External links

- Pro Slovo.

- Salimonovych, L. Unread "Slovo" (Непрочитане «Слово»). Ukrayina Moloda. 12 August 2005