Battle of Siffin

The Battle of Siffin (Arabic: يوم صفين, romanized: Yawm Ṣiffīn, lit. 'the day of Siffin') was fought between the Rashidun army of the fourth caliph Ali (r. 656–661) led by Malik ibn al-Harith and the Syrian forces of Mu'awiya commanded by Amr ibn al-As. The battle took place at the village of Siffin in Syria on the banks of the Euphrates in July 657.

| Battle of Siffin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Fitna | |||||||

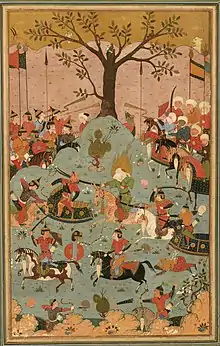

.jpg.webp) The Battle of Siffin as depicted in the 14th-century manuscript of the Tarikh-i Bal'ami | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate | Muawiya's forces of Syria | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000 men[1] | 120,000 men[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 25,000[2] | 40,000[2] | ||||||

After the third caliph Uthman (r. 644–656) was assassinated in June 656, Ali was elected caliph in Medina. His election was opposed by most of the Quraysh led by Muhammad's companions Talha ibn Ubayd Allah and Zubayr ibn al-Awwam and Muhammad's widow Aisha. After Ali defeated the rebels in the Battle of the Camel in December 656, turned his attention toward Mu'awiya, the governor of Syria. The latter refused to acknowledge Ali's rule and declared war on the caliph to avenge his Umayyad kinsman Uthman's death. Mu'awiya formed an alliance with Amr ibn al-As, the former governor of Egypt, against Ali. In the first week of June 657, both parties engaged in days of skirmishes interrupted by a month-long truce on 19 June.

The main battle between the two armies commenced on 26 July and lasted for two days. Mu'awiya initially had the upper hand but the balance moved in Ali's favor. After overwhelming odds of defeat, the Syrians called for arbitration to settle the conflict. Mu'awiya and Ali's representatives Amr and Abu Musa al-Ash'ari representatives respectively agreed to the terms of the arbitration, which ended inconclusively in April 658. In the aftermath of the battle, a group of Ali's supporters, the Kharijites, defected the caliph considering the arbitration to be un-Islamic.

Location

The battlefield was at Siffin, a ruined Byzantine-era village situated a few hundred yards from the right bank of the Euphrates in the vicinity of Raqqa in present-day Syria.[3] It has been identified with the modern village of Abu Hureyra in the Raqqa Governorate.[4]

Background

Uthman's assassination

The reign of the third caliph, Uthman, was marked by widespread nepotism and moral degradation.[5] In 656 CE, as the public dissatisfaction with despotism and corruption came to a boiling point, Uthman was assassinated by the rebels in a raid on his residence.[6]

Ali had acted as the mediator between the rebels and Uthman.[7] According to Jafri, though he condemned Uthman's murder, Ali likely regarded the resistance movement as a front for the just demands of the poor and the disenfranchised.[8] His son, Hasan, was injured by the enraged mobs while standing guard at Uthman's residence at the request of Ali.[9]

Shortly after Uthman's assassination, the crowds in Medina turned to Ali for leadership and were turned down initially.[10] Aslan attributes Ali's initial refusal to the polarization of the Muslim community after Uthman's murder.[11] On the other hand, Durant suggests that, "[Ali] shrank from drama in which religion had been displaced by politics, and devotion by intrigue."[12] Nevertheless, in the absence of any serious opposition and urged particularly by the Iraqi dissidents and the Ansar, Ali eventually assumed the role of caliph and Muslims filled the Prophet's Mosque in Medina and its courtyard to pledge their allegiance to him.[13] According to Shaban, the atmosphere of tumult after Uthman's murder might have compelled Ali into accepting the caliphate to prevent further chaos.[14]

Soon after assuming power, Ali moved to dismiss most of Uthman's governors whom he considered corrupt, including Muawiya, Uthman's cousin.[15] Under a lenient Uthman, according to Madelung, Muawiya had built a parallel power structure in Syria that mirrored the despotism of the Byzantine empire.[16] He had been appointed as the governor of Syria by the second caliph, Umar, and then reconfirmed by Uthman.[17] It has been noted that Muawiya was a late convert to Islam whose mother, Hind, was responsible for mutilating the body of Muhammad's uncle, Hamza.[18] Muawiya's father, Abu Sufyan, had led the Meccan armies against the Muslims during the Battle of Uhud and the Battle of Khandaq.[19]

Ali rejected the suggestion to delay the plans for deposing Muawiya until his own power had been consolidated. According to Hazleton, in response to this suggestion, Ali commented that he would not compromise his faith and confirm Muawiya, a contemptible man in Ali's view, as governor even for two days.[20]

Muawiya's declaration of war

When Muawiya refused to return to Medina, Ali wrote to him that a public pledge in Medina was binding on Muawiya, asserting that this pledge was made by the same people who had pledged their allegiance to the previous caliphs.[21] In response, Muawiya asked for time to seek the views of Syrians, in a move that has been interpreted as a delaying tactic for Muawiya to mobilize his forces against Ali.[22] According to Madelung, Muawiya also launched a propaganda campaign among Syrians which appealed to their patriotism and posing himself as Uthman's next of kin, responsible for his avenge.[23]

Through a representative, Muawiya also secretly informed Ali that he would recognize the caliphate of Ali if he was willing to concede Syria and Egypt to Muawiya.[24] This proposal was made in secret, according to Madelung, because a public proposal would have exposed the fraudulence of Muawiya's claims of revenge for Uthman.[25] Ali likely perceived this proposal as a ruse from Muawiya to take over the caliphate step by step.[26]

When his proposal was rejected, Muawiya declared war on Ali in a letter on behalf of the Syrians, with the objectives of killing the murderers of Uthman, deposing Ali, and establishing a Syrian council (shura) to appoint the next caliph, presumably Muawiya.[27] Regarding this letter, Madelung observes that[28]

Uthman had meant little to him [Muawiya], he [Muawiya] had done nothing to aid him [Uthman], and felt no personal obligation to seek revenge. Yet he [Muawiya] immediately sensed the political utility of a claim of revenge for the blood of the wronged caliph, as long as he, Muawiya, could decide on whom to pin the blame.

A number of sources further suggest that the instructions to punish the rebels had been planted by Marwan at the instigation of Muawiya, in order to precipitate the downfall of Uthman.[29] It is alleged that Muawiya deliberately withheld the reinforcements requested by the besieged Uthman shortly before his murder.[30]

In response to Muawiya's declaration of war, Ali wrote to him, pointing out that Muawiya was not Uthman's next of kin to avenge his death but that he was still welcome to bring his case to Ali's court of justice. He then challenged Muawiya to offer any evidence that would incriminate him in the murder of Uthman. Ali also challenged Muawiya to name any Syrian who would qualify for a council.[31]

Muawiya also used this window to expand his alliances.[32] Notably, with the promise of governorship of Egypt, Muawiya brought Amr ibn al-As to his camp.[33] Amr, a political strategist, was widely believed to be the illegitimate son of Muawiya's father, Abu Sufyan.[34] Amr was also a prime instigator in the murder of Uthman and had publicly taken some credit for it.[35] However, Amr later distanced himself from Uthman's murder and allied with Muawiya, both accusing Ali instead.[36]

Start of the hostilities

Following Muawiya's declaration of war, Ali called a council of Islamic ruling elite which urged him to fight Muawiya.[37] Nevertheless, Ali barred his followers from cursing Syrians, adding that it might jeopardise any remaining hopes to avoid the imminent bloodshed.[38] Early in the summer of 657 CE, Ali's army reached Siffin, west of the Euphrates, where Muawiya's forces had been waiting for them.[39] The Syrian forces were ordered to cut off the enemies' access to drinking water. Muawiya, according to Madelung, might have been carried away by his propaganda that these were the murderers of Uthman who should be made to die of thirst."[40] Ali's forces, however, were able to drive off the Syrians and seize control of the watering place. Ali allowed Syrians to freely access the water.[41]

Then, for weeks, the two sides negotiated.[42] In the first week of June 657, the armies of Mu'awiya and Ali met at Siffin near Raqqa and engaged in days of skirmishes interrupted by a month-long truce on 19 June.[43] Notably, Muawiya repeated his proposition to recognize Ali in return for Syria and Egypt, which was rejected again.[44] In turn, Ali challenged Muawiya to a one-on-one duel to settle the matters and avoid the bloodshed.[45] This offer was declined by Muawiya.[46]

The negotiations failed on 18 July 657 and the two side readied for the battle.[47] Medinans, Kufans, and Basrans made up the rank and file of Ali's army.[48] A considerable number of Muhammad's companions were present in Ali's army.[49] Muawiya's army largely consisted of latecomers to Islam who had been drawn to the frontier provinces by the prospect of rich booty.[50]

The main engagement

The main battle began on Wednesday, 26 July, and continued to Friday or Saturday morning.[51] Ali fought with his men on the frontline while Muawiya led from his pavilion.[52] At the end of the first day, having pushed back Ali's right wing, Muawiya had fared better overall.[53] Mu'awiya's forces were led by Amr ibn al-As whereas Ali's troops were commanded by Malik ibn al-Harith al-Ashtar.[54] Habib ibn Maslama was in the charge of Mu'awiya's left wing.[55]

On the second day, Muawiya concentrated his assault on Ali's left wing but the tide of war turned and Syrians were pushed back.[56] Muawiya fled his pavilion and took shelter in an army tent.[57] On this day, Ubayd Allah, son of the second caliph, Umar, and a triple murderer, was killed fighting for Muawiya.[58] On the other side, Ammar ibn Yasir, an octogenarian companion of Muhammad, was killed fighting for Ali.[59] According to both Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim, a hadith attributed to Muhammad had prophesied Ammar's death, adding that, "He [Ammar] will invite them [Muawiya's army] to God and they will invite him to hellfire."[60]

On the third day, despite appeals from his army, Muawiya refused to agree to a duel with Ali to end the slaughter.[61] After another indecisive day, the battle continued throughout the night in what is remembered as the Night of Shrieking.[62]

By next morning, the balance had moved in Ali's favor.[63] Before noon, however, some of the Syrians raised copies of the Quran on their lances, shouting the same line, "Let the book of God be the judge between us." The fighting stopped.[64] Of the estimated casualties, Ali was estimated to have lost 25,000 men, while Muawiyah lost 45,000.[65][66][67] According to Theophilus of Edessa (d. 785), both sides suffered a loss of 60,000 men.[68]

Arbitration

It is believed that Muawiya adopted the above arbitration strategy when he was informed by his top general, Amr ibn al-As, that Syrians could not win the battle.[69]

Faced with an appeal to their holy book, Ali's forces stopped fighting, despite the warnings from Ali that Muyawiya was not a man of religion and raising the Quran was for deception.[70] Ash'ath ibn Qays al-Kindi, the most powerful tribal leader of Kufa, reportedly told Ali that no one from his tribe would fight for him if he did not accept the call to arbitration.[71] Ali's appeals to his army were also met with threats of mutiny, in particular, by those who would later become leading Kharijites.[72] Ali was therefore compelled to recognize these demands and recall his top commander, al-Ashtar, who had advanced far towards the Syrian camp.[73] It was agreed that representatives from both side would arbitrate in accordance with the Quran.[74]

When the details of Muawiya's proposal became clear, a considerable minority in Ali's army objected to arbitration, evidently realizing the political motivations of Muawiya.[75][76] This minority demanded that Ali resume the war.[77] Even though Ali is reported to have favored it, he declined this proposal, pointing out that this minority would be crushed by the majority and the Syrians who all demanded arbitration.[78] Some of the dissidents left for Kufa, while others stayed, hoping that Ali might later change his mind.[79] Facing strong peace sentiments in his army, Ali accepted the arbitration proposal, against his own judgement.[80]

The majority in Ali's army now pressed for the reportedly neutral Abu Musa al-Ashari as their representative, despite Ali's objections about Abu Musa's political naivety.[81] Nevertheless, the arbitration agreement was written and signed by both parties on 2 August, 657 CE.[82] Abu Musa represented Ali's army while Muawiya's top general, Amr ibn al-As, represented Muawiya's forces.[83] The two representatives committed to adhere to the Quran and Sunnah, and to save the community from war and division, a clause placed evidently to appease the peace party.[84] However, it has been noted that Amr was far from neutral and acted solely for the benefit of Muawiya.[85]

Two days after this agreement the two armies left the battlefield.[86] Upon his return to Kufa, Ali largely succeeded in regaining the support of the opponents of arbitration.[87] He reminded the remaining opponents that they had opted for the arbitration despite his warnings.[88] They agreed and told Ali that they had repented for their sins and demanded that Ali do the same.[89] Ali, however, upheld the formal agreement with Muawiya and the dissidents gradually formed the Kharijites, meaning the seceders, who later took up arms against Ali in the Battle of Nahrawan.[90] Kharijites have been regarded as the forerunners of Islamic extremists.[91]

After several months of preparation, the two arbitrators met together, first at Dumat al-Jandal and then at Udhruh.[92] The proceedings lasted for weeks, likely extending to mid April 658 CE.[93][94] At Dumat al-Jandal, the arbitrators reached the verdict that Uthman had been killed wrongfully and that Muawiya had the right to seek revenge.[95] This has been viewed as a political verdict, rather than a judicial one, and a blunder of the naive Abu Musa.[96] The verdict strengthened the Syrians' support for Muawiya and weakened the position of Ali.[97]

According to Madelung, the second meeting at Udhruh broke up in disarray.[94] At its conclusion, one account is that Abu Musa, per his agreement with Amr, deposed both Ali and Muawiya and called for a council to appoint the new caliph. When Amr took the stage, he confirmed that the arbitrators had indeed agreed on deposing Ali but added that Muawiya should remain in power, thus violating his agreement with Abu Musa.[98] The Kufan delegation reacted furiously to Abu Musa's concessions.[99] He was disgraced and fled to Mecca, whereas Amr was received triumphantly by Muawiya on his return to Syria.[100]

Aftermath

After the conclusion of the arbitration, Syrians pledged their allegiance to Muawiya as the next caliph in 659 CE.[101] Ali denounced the conduct of the two arbitrators as contrary to the Quran and began to organize a new expedition to Syria.[102] However, with the news of their violence against civilians, Ali had to postpone his campaign for Syria to subdue Kharijites in the Battle of Nahrawan in 658 CE.[103] Upon learning that Muawiya had declared himself caliph, Ali broke off all communications with him and introduced a curse on him, following the precedent of Muhammad.[104] Muawiya reciprocated by introducing a curse on Ali, his sons, and his top general.[105] Just before embarking on his second campaign to Syria in 661 CE, when praying at the Mosque of Kufa, Ali was assassinated by a Kharijite fanatic.[106]

References

Citations

- Ibn Yaqubi, Ahmad (872). Tarikh Al Yaqubi. Armenia: Ahmad Ibn Yaqubi. p. 188. ISBN 9786136166070.

- Muir, William (1891). The Caliphate, its Rise and Fall. London: William Muir. p. 261.

- Aslan (2011, p. 136)

- Lecker (2021)

- Hazleton (2009, p. 86). Bodley (1946, p. 349). Madelung (1997, p. 81). Momen (1985, p. 21). Abbas (2021, p. 117). Glassé (2001, p. 423)

- Abbas (2021, p. 119). Glassé (2001, p. 423)

- Poonawala (1982). Hazleton (2009, pp. 93, 95). Abbas (2021, pp. 122, 123)

- Jafri (1979, pp. 63, 64)

- Veccia Vaglieri (2021b). Abbas (2021, p. 125). Hazleton (2009, p. 95). Jafri (1979, p. 62). Nasr & Afsaruddin (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 142). Momen (1985, p. 22). Abbas (2021, p. 129). Gleave (2021)

- Aslan (2011, pp. 131, 132)

- Abbas (2021, p. 128)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 141, 142). Hazleton (2009, p. 99). Jafri (1979, p. 63). Rogerson (2006, pp. 286, 287). Gleave (2021)

- Shaban (1971, p. 71)

- Rogerson (2006, p. 310). Aslan (2011, p. 136). Bowering et al. (2013, p. 31)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 148, 197). Abbas (2021, p. 134). Hazleton (2009, p. 183)

- Hazleton (2009, p. 127). Hinds (2021)

- Hinds (2021). Abbas (2021, p. 60). Rogerson (2006, pp. 302, 303)

- Hazleton (2013, pp. 127, 197, 227). Momen (1985, p. 21). Cooperson (2000, p. 25). Rogerson (2006, pp. 302, 303). Hinds (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 148). Hazleton (2009, p. 129). Abbas (2021, pp. 134, reaffirming his as governor)

- Madelung (1997, p. 194). Hazleton (2009, p. 129). Abbas (2021, p. was binding on him in Syria). Rogerson (2006, p. 302). Veccia Vaglieri (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 195). Abbas (2021, p. a delaying tactic)

- Madelung (1997, p. 195). Hazleton (2009, p. 133). Abbas (2021, p. 144). Rogerson (2006, pp. 301, 302)

- Madelung (1997, p. 203). Gleave (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 203)

- Abbas (2021, p. a mere ruse from Muawiya). Madelung (1997, p. 204)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 204, 205). Hazleton (2009, pp. 130, 136). Hinds (2021)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 186, 205, 228)

- Hazleton (2021, p. 183). Abbas (2021, p. having advised Marwan)

- Hazleton (2021, p. 183). Abbas (2021, p. having advised Marwan)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 205, 206)

- Hinds (2021). Abbas (2021, p. expand his alliances)

- Hinds (2021). Abbas (2021, p. devious power play). Rogerson (2006, pp. 304, 305)

- Madelung (1997, p. 185). Abbas (2021, p. the illegitimate son). Rogerson (2006, p. 305)

- Madelung (1997, p. 187). Rogerson (2006, pp. 304, 305)

- Madelung (1997, p. 187). Rogerson (2006, pp. 304, 305). Hinds (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 215). Rogerson (2006, pp. 303, 304)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 218, 219)

- Madelung (1997, p. 226). Abbas (2021, p. Ali reached Siffin). Donner (2010, pp. 161)

- Madelung (1997, p. 226)

- Madelung (1997, p. 227). Abbas (2021, p. access to the water). Rogerson (2006, pp. 306)

- Lecker (2021)

- Madelung 1977, p. 225–226, 229.

- Hazleton (2009, p. 196). Abbas (2021, p. splitting the Muslim empire)

- Madelung (1997, p. 238). Abbas (2021, p. on the verge of a decisive victory). Hazleton (2009, pp. 198, 199). Rogerson (2006, pp. 307, 308). Bowering et al. (2013, p. 31)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 198, 235). Hazleton (2009, p. 197). Abbas (2021, p. Muawiya obviously declined the offer). Rogerson (2006, p. 306)

- Madelung (1997, p. 231). Bowering et al., p. 31). Donner (2010, pp. 161)

- Rogerson (2006, p. 307)

- Momen (1985, p. 25)

- Momen (1985, p. 25)

- Madelung (1997, p. 232). Rogerson (2006, p. 307). Donner (2010, pp. 161)

- Hazleton (2009, p. 198). Madelung (1997, p. 234)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 232, 233)

- Lakhani, Kazemi & Lewisohn 2006, p. 110.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 232–233.

- Madelung (1997, p. 234)

- Madelung (1997, p. 234). Abbas (2021, p. flee from his pavilion)

- Madelung (1997, p. 233)

- Madelung (1997, p. 234). Abbas (2021, p. faithful friend Ammar)

- Abbas (2021, p. invite him to hellfire). Lecker (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 235). Abbas (2021, p. Ali was offering a fair proposal). Hazleton (2009, p. 196)

- Hazleton (2009, p. 197). Madelung (1997, p. 237)

- Madelung (1997, p. 238). Abbas (2021, p. on the verge of a decisive victory). Hazleton (2009, p. 198). Rogerson (2006, pp. 307, 308)

- Madelung (1997, p. 238). Hazleton (2009, pp. 198, 199). Abbas (2021, pp. this was a call for arbitration). Rogerson (2006, p. 308). Bowering et al. (2013, p. 31)

- William Muir, The Caliphate, its Rise and Fall (London, 1924) page 261

- Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Ch. L, Pgs. 98-99. New York: Fred de Fau and Co. Publishers (1906).

- Edward Gibbon, The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire (London, 1848) volume 3, p.522

- Hoyland 2011, p. 147.

- Madelung (1997, p. 238). Abbas (2021, p. on Amr's cunning advice). Hazleton (2009, p. 198). Rogerson (2006, p. 308). Mavani (2013, pp. 98). Aslan (2011, p. 137). Bowering et al. (2013b, p. 43). Glassé (2001, p. 40). Nasr & Afsaruddin (2021). Veccia Vaglieri (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 238). Abbas (2021, pp. you have been cheated). Rogerson (2006, pp. 308). Hazleton (2009, pp. 199–201)

- Poonawala (1982). Shaban (1971, p. 75)

- Madelung (1997, p. 238)

- Madelung (1997, p. 238). Abbas (2021, p. agree to arbitration). Hazleton (2009, p. 199)

- Madelung (1997, p. 239). Abbas (2021, p. nominated their representatives). Hazleton (2009, p. 200). Bowering et al. (2013b, p. 43)

- Madelung (1997, p. 239). Abbas (2021, pp. were rethinking their actions). Hazleton (2009, p. 202)

- Britannica (2016)

- Madelung (1997, p. 239)

- Madelung (1997, p. 239)

- Madelung (1997, p. 239)

- Madelung (1997, p. 241). Donner (2010, pp. 161)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 241, 242). Hazleton (2009, p. 211). Rogerson (2006, p. 308). Bowering et al. (2013b, p. 43). Donner (2010, pp. 161). Poonawala (1982). Veccia Vaglieri (2021c)

- Madelung (1997, p. 243)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 241, 242). Abbas (2021, p. politically ambitious Kufan). Hazleton (2009, pp. 210, 211). Rogerson (2006, p. 308). Bowering et al. (2013b, p. 43)

- Madelung (1997, p. 243). Abbas (2021, p. the mandate of the arbitration). Rogerson (2006, p. 309)

- Madelung (1997, p. 245). Rogerson (2006, p. 309). Bowering et al. (2013b, p. 43)

- Madelung (1997, p. 247)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 248, 249). Abbas (2021, pp. brought many of them out). Rogerson (2006, pp. 311, 313). Donner (2010, p. 163). Veccia Vaglieri (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 248). Abbas (2021, pp. never approved of this cessation, blinded by Muawiya's strategy). Hazleton (2009, p. 204). Jafri (1979, p. 87). Rogerson (2006, p. 310)

- Madelung (1997, p. 249). Donner (2010, p. 162). Hazleton (2009, pp. 204). Poonawala (1982)

- Madelung (1997, p. 249). Abbas (2021, p. came to be known as the battle of nahrawan). Jafri (1979, p. 87). Rogerson (2006, p. 310). Hazleton (2009, pp. 204). Bowering et al. (2013, p. 31). Levi Della Vida (2021). Donner (2010, p. 162). Poonawala (1982). Veccia Vaglieri (2021)

- Hazleton (2009, p. 144). Abbas (2021, p. 152)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 254, 255). Hazleton (2009, p. 210). Poonawala (1982)

- Donner (2010, p. 162). Madelung (1997, pp. 254, 255). Hazleton (2009, p. 210)

- Rogerson (2006, p. 312). Madelung (1997, p. 257)

- Madelung (1997, p. 255). Abbas (2021, p. Uthman had indeed been wrongfully killed). Aslan (2011, p. 137). Poonawala (1982). Veccia Vaglieri (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 256). Rogerson (2006, p. 312)

- Madelung (1997, p. 255). Jafri (1979, p. 65). Momen (1985, p. 25). Bowering et al. (2013, p. 31). Donner (2010, pp. 162, 163). Poonawala (1982)

- Abbas (2021, p. it was all staged-managed). Rogerson (2006, pp. 311, 312). Glassé (2001, p. 40). Donner (2010, p. 165). Poonawala (1982)

- Madelung (1997, p. 257). Hazleton (2009, p. 212)

- Madelung (1997, p. 257). Hazleton (2009, pp. 212). Rogerson (2006, p. 312)

- Madelung (1997, p. 257). Hazleton (2009, pp. 212). Rogerson (2006, p. 312). Bowering et al., p. 31). Donner (2010, p. 163). Hinds (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 257). Glassé (2001, p. 40). Poonawala (1982). Veccia Vaglieri (2021)

- Madelung (1997, p. 259). Abbas (2021, pp. `Ali knows far more of God than you do', came to be known as the battle of nahrawan). Momen (1985, p. 25). Rogerson (2006, p. 313). Donner (2010, p. 163)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 257, 258). Rogerson (2006, p. 312)

- Madelung (1997, p. 258)

- Jafri (1979, p. 65). Momen (1985, p. 25). Aslan (2011, p. 137). Bowering et al. (2013, p. 31). Meri (2006, p. 37). Glassé (2001, p. 40). Donner (2010, p. 166)

Sources

- Abbas, Hassan (2021). The Prophet's Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300252057.

- Aslan, Reza (2011). No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam. Random House. ISBN 9780812982442.

- Bowering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Kadi, Wadad; Mirza, Mahan; Stewart, Devin J.; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim, eds. (2013). "Ali b. Abi Talib (ca. 599–661)". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691134840.

- Bowering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Kadi, Wadad; Mirza, Mahan; Stewart, Devin J.; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim, eds. (2013b). "Arbitration". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691134840.

- "Battle of Siffin". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2016.

- Donner, Fred M. (2010). Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674064140.

- Glassé, Cyril (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. AltaMira Press. ISBN 9780759101890.

- Gleave, Robert M. (2021). "Ali b. Abi Talib". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Third ed.). Brill Reference Online.

- Hazleton, Lesley (2009). After the Prophet: The Epic Story of the Shia-Sunni Split in Islam. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780385532099.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2011). Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781846316982.

- Hinds, M. (2021). "Muawiya I". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Reference Online.

- Jafri, S.H.M (1979). Origins and Early Development of Shia Islam. London: Longman.

- Lakhani, M. Ali; Kazemi, Reza Shah; Lewisohn, Leonard (2006). The Sacred Foundations of Justice in Islam: The Teachings of ʻAlī Ibn Abī Ṭālib. World Wisdom Inc. ISBN 9781933316260.

- Lecker, M. (2021). "Siffin". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Reference Online.

- Levi Della Vida (2021). "Kharidjites". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Reference Online.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64696-3.

- Mavani, Hamid (2013). Religious Authority and Political Thought in Twelver Shi'ism: From Ali to Post-Khomeini. Routledge. ISBN 9780415624404.

- Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415966900.

- Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780853982005.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Afsaruddin, Asma (2021). "Ali". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Poonawala, I.K. (1982). "Ali b. Abi Taleb I. Life". Encyclopaedia Iranica (Online ed.).

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2006). The Heirs of the Prophet Muhammad: And the Roots of the Sunni-Shia Schism. Abacus. ISBN 9780349117577.

- Shaban, Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Ḥayy (1971). Islamic History: A New Interpretation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29131-6.

- Veccia Vaglieri, L. (2021). "Ali b. Abi Talib". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Reference Online.

- Veccia Vaglieri, L. (2021b). "(Al-)Ḥasan B. Ali B. Abi Talib". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Reference Online.

- Veccia Vaglieri, L. (2021c). "Al-Ashari, Abu Musa". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Reference Online.