Siege of Bukhara

The Siege of Bukhara took place during the Mongol conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire, in March 1220. Genghis Khan, ruler of the Mongol Empire, had launched a multi-pronged assault on the Khwarazmian Empire, ruled by Shah Muhammad II. While the Shah organized plans to defend each of his major cities individually, the Mongols laid siege to the border town of Otrar and then struck further into Khwarazmia.

| Siege of Bukhara (1220) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire | |||||||

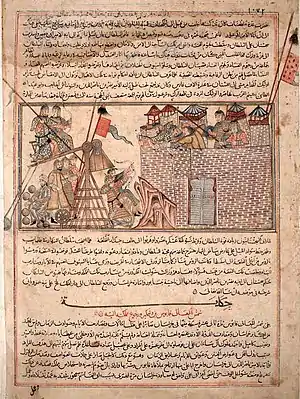

A illustration of Mongols conducting a siege, from Rashid al-Din's Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire | Khwarazmian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gür-Khan | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| City garrison | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Modern estimates range from 30,000 to 50,000 | Modern estimates range from 2,000 to 20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Most of the garrison | ||||||

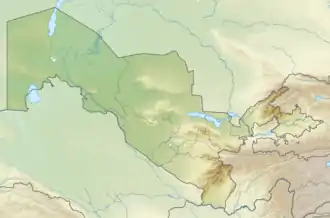

Bukhara Location of the siege on a map of modern Uzbekistan  Bukhara Bukhara (West and Central Asia) | |||||||

The city of Bukhara was a major trading and cultural centre of the Khwarazmian Empire, but was located far from the border with the Mongols, and so the Shah allocated fewer than 20,000 soldiers to defend it. However, a Mongol force, estimated to number between 30,000 and 50,000 men, managed to traverse the Kyzyl Kum desert, previously thought impassable for large armies. Bukhara was caught completely by surprise, and after a sortie was annihilated, the outer city surrendered within three days. Khwarazmian loyalists continued to garrison the citadel for less than two weeks, before it too was breached.

The Mongol army killed all in the citadel, and enslaved most of the populace. The work of skilled craftsmen and artisans was appropriated by the Mongols, while others were conscripted into the armies. Although fires burnt Bukhara to the ground, the devastation was relatively mild; within a fairly short space of time, the city was once again a centre of trade and learning, and profited greatly from the Pax Mongolica.

Background

On the eve of the Mongol invasion, Yaqut al-Hamawi's geographical survey described Bukhara as 'among the greatest cities of Central Asia'.[1][lower-alpha 1] With a population of close to 300,000 and a library of 45,000 books, the city rivalled Baghdad as a centre of learning and culture.[3][4] The Po-i-Kalyan mosque, which had originally been commissioned in 1121, was one of the largest in the world, and it contained the Kalyan minaret.[5] The city was guarded by the Ark of Bukhara, a fortress established in the fifth century which served as a citadel, while the farmlands were expertly and extensively irrigated with water from the River Zeravshan.[6]

The city had been long been under the rule of the Qarakhanids, who had historically controlled many of the richest cities in the area, such as Samarkand, Tashkent and Fergana.[7] Nominally vassals of the Qara-Khitai khanate, the Qarakhanids were allowed to operate almost autonomously, due to their large population and territory; by 1215, they had been subjugated by the Khwarazmians, also former vassals of the Qara-Khitai, who had expanded from Gurganj into the power vacuum left by the collapsing Seljuk Empire.[8][9]: 32–33 In 1218, Khwarazmshah Muhammad II was Sultan of Hamadan, Iran and Khorasan, and had established dominion over the Ghurids and the Eldiguzids.[8] The Khwarazmian Empire had usurped the Qara-Khitai, which had already been destabilized by refugees fleeing the conquests of Genghis Khan, who had begun to establish hegemony over the Mongol tribes.[10]

Following the defeat of their shared enemy, the Naiman prince Kuchlug, relations between the Mongols and the Khwarazmids were initially strong;[11]: 30–31 however, the Shah soon grew apprehensive regarding his new eastern neighbour. The chronicler al-Nasawi attributes this change in attitude to the memory of an unintended earlier encounter with Mongol troops, whose speed and mobility frightened the Shah.[12] In 1218, the Shah allowed Inalchuq, the governor of Otrar, to arrest an entire Mongol trade caravan, and to seize its goods; Genghis, seeking a diplomatic resolution, sent three envoys to Urgench, whom Muhammad humiliated, publicly executing one. Outraged, Genghis left his war against the Jin, leaving only a minimal force behind, and rode westwards with a great part of his army.[13]

Prelude

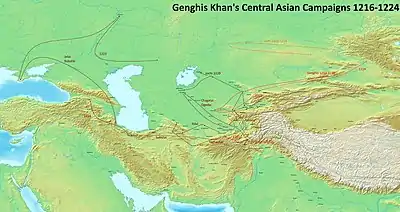

There are conflicting reports as to the size of the total Mongol invasion force — estimates have ranged from as few as 75,000 to as many as 700,000, although anything over 200,000 is considered an exaggeration by modern historians.[lower-alpha 2] The uncertainty is made worse by the high flexibility and efficiency of the Mongol force's operational structure, allowing it to separate and coalesce at will.[19] The Mongol forces arrived in Khwarazm in waves: first, a vanguard led by Jochi and Jebe crossed the treacherous Tien Shan passes, and started laying waste to the towns of the eastern Fergana Valley; then, another army led by Chagatai and Ogedai descended onto Otrar and besieged it.[20]: 269–272 Genghis soon arrived with his youngest son Tolui, and he then split the invasion force into four divisions: while Chagatai and Ogedai were to remain besieging Otrar, Jochi was to head northwest in the direction of Urgench, and a minor force was sent to take Khujand, but Genghis himself took Tolui and around half the army — between 30,000 and 50,000 men — and headed westwards.[18]: 113

The Khwarazmshah faced many problems. His empire was vast and newly formed, with a still-developing administration.[21]: 373–380 In addition, his mother Terken Khatun still wielded substantial power in the realm - one historian termed the relationship between the Shah and his mother as 'an uneasy diarchy', which often acted to Muhammad's disadvantage.[7]: 14–15 The Shah also distrusted most of his commanders, with the only exception being his eldest son and heir Jalal al-Din, whose military acumen had been critical at the Irgiz River the previous year.[11]: 31 If he had sought open battle, as many of his commanders wished, he would certainly have been greatly outmatched in quantity of troops, let alone quality.[22] The Shah thus made the decision to distribute his forces as garrison troops inside his most important towns, such as Samarkand, Merv and Nishapur.[13] Since it was supposedly far from the theatre of war, Bukhara was allotted relatively few troops.[lower-alpha 3] The inhabitants, and the Shah, were thus horrified to see the Khan's army appear in front of the city, having crossed 300 mi (480 km) of the trackless Kyzyl Kum desert, previously thought impassable by a major force; this expedition has been lauded by some historians as one of the greatest manoeuvres in history.[19][25]: 63–64 The Khan and his commanders, having deduced the Shah's strategy, had not only utilized both the innate speed and hardiness of their own horse archers and captive local guides to traverse a network of wells and waterholes across the desert.[20]: 273 One historian speculates that they had also guaranteed certain surprise through the use of scouting screens over large distances.[25]: 65

Siege

The Shah was caught completely unaware — he had anticipated that Genghis would attack Samarkand first, whereupon both his field army and the garrison at Bukhara could relieve the siege. The Khan's march through the Kyzyl Kum had left his field army impotent, unable to either engage the enemy or help his people.[24] The chronicler Juvaini records that the garrison at Bukhara was commanded by a certain Gür-Khan[23]: 103 — one historian has suggested that this may have been Jamukha, an old friend-turned-enemy of Genghis.[21]: 119–20 Most historians consider this unlikely, as Jamukha is commonly attested to have been executed in 1206.[26][24]

The major military action of the siege came on the second or third day, when the Sultan's troops, numbering between 2,000 and 20,000, sallied forth; Juvaini records that they were annihilated by the Mongols on the banks of the river:

When these forces reached the banks of the Oxus, the patrols and advance parties of the Mongol army fell upon them and left no trace ... On the following day from the reflection of the sun the plain seemed to be a tray filled with blood.

One historian notes that the sortie, which was conducted solely by the Sultan's auxiliary troops and not by the city garrison, may just have been an attempt to flee; he attributes their willingness to leave to the fact that Bukhara was a very recent Khwarazmian conquest, having been taken from the Qarakhanids less than a decade previously.[27] On the following day the town elders surrendered the city to the Khan's army; thenceforth the only resistance came from a small band of loyalists in the citadel. The citadel of the Ark was built to the highest specifications, but the Khan had brought experts in siege warfare from China; a breach was made after ten days using incendiary and gunpowder weapons, and the citadel was taken in a fortnight.[11]: 34

Aftermath

Having entered the city, Genghis Khan is recorded to have given a speech at the Friday Mosque, which later gained fame as a theological rationalization for Mongol destruction.

O People, know that you have committed great sins, and that the great ones among you have committed these sins. If you ask me what proof I have for these words, I say it is because I am the punishment of God. If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.

The small amount of resistance in the citadel would prove detrimental to the rest of Bukhara; the Mongols set fires in an attempt to flush out the holdouts, but since most structures in the city were wooden, the soon-uncontrollable fire reduced most of the city, including the famed library, to cinders.[27] Most of the stone structures which were left standing were razed by the Mongols, including the first Po-i-Kalyan mosque; although the Kalyan minaret within the mosque was left standing.[28]

Although all inside the citadel were massacred, the population was not wholly exterminated, unlike other cities such as Merv and Urgench. Instead, the people were evacuated and divided up: skilled artisans and craftsmen were attached to the Mongol army; most of the women were raped and taken as concubines; and the remaining men of fighting age were conscripted into the Mongol forces.[31] These conscripts would be used as human shields in the sieges of Samarkand and Gurganj, which would follow afterwards in 1220 and 1221.[25]: 64–65 Shah Muhammad would die destitute on an island in the Caspian Sea, while the Mongols systematically besieged and took every major city in his empire;[20]: 289 his son Jalal al-Din would put up the most resistance but was eventually crushed at the Battle of the Indus.[18]: 113

Legacy

While extremely devastating in the short-term, the siege would not be the city's end; in fact, within two decades, the city was once again serving as an important centre of trans-Asian trade.[32] Proto-bureaucratic elements were put into place reasonably quickly, under the auspices of a new post called daruyaci; many of the institutions that were later put into place took inspiration from the Qara-Khitai, which one historian has called 'a prototype Mongol Empire'.[27] Records of a Taoist delegation to the area in 1221 reveal that Samarkand, and presumably Bukhara also, was beginning to be repopulated with Chinese and Khitan artisan settlers;[33] the area was still unstable, however, with a Khwarazmian bandit chief managing to assassinate a Bukharan darughachi around that time. The former cities of Khwarazm later became the main sources of income for the treasury of Ogedai, and would become the key cities of the Chagatai Khanate; Bukhara, along with Samarkand, would even later be the home cities of the great conqueror Timur.[34] It would also regain its religious importance, becoming the most important centre of Sufism in Central Asia; the shrine around the tomb of Sayf al-Din al-Bakharzi was one of the most richly endowed properties in the region.[35]

References

Notes

- This claim is corroborated by other thirteenth-century writers, such as al-Tha'alibi and al-Qazwini; the latter describes Bukhara as an 'assembly, repository of the wise, source of rational science'.[2] However, al-Hamawi gives a less flattering portrait of the densely-populated centre, citing poets who criticize the 'filth and prevalence of uncleanliness in its streets'.[1]

- The highest estimates were made by classical Muslim historians such as Juzjani and Rashid al-Din.[14][15] Rossabi indicates that the total Mongol invasion force cannot have been more than 200,000;[16] while Smith gives an approximation of around 130,000.[17] The minimum figure of 75,000 is given by Sverdrup, who hypothesizes that a tumen had often been overestimated in size.[18]: 109, 113

- As with the Mongol army, there is also debate as to the size and composition of the Shah's forces. Juvaini states that 50,000 were sent to aid Otrar, and states that there were at least 20,000 in Bukhara.[23]: 82 Sverdrup, however, claims that there were between two and five thousand men at Bukhara.[24]

References

- al-Hamawi, Yaqut (c. 1220). Mu'jam ul-Buldān معجم البلدان [Dictionary of Countries] (in Arabic). pp. 353–4.

- al-Qazwini, Zakariya (c. 1272). Āṯār al-belād wa-akhbār al-ʿibād [Monuments of the Lands and Historical Traditions about Their Peoples] (in Arabic). p. 510.

- Modelski, George (2007). "Central Asian world cities (XI – XIII century): a discussion paper". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Ahmad, S. Maqbul (2000). "8: Geodesy, Geology, and Mineralogy; Geography and Cartography". In Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, M.S. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV / #2. UNESCO Publishing. p. 217. ISBN 9231034677.

- Emin, Leon (1989). Muslims in the USSR Мусульмане в СССР [Muslims in the USSR]. Moscow: Novosti Press Agency Publishing House. pp. 8–10. OCLC 20802477.

- Nelson Frye, Richard (1965). Bukhara: The Medieval Achievement. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 1568590482.

- Golden, Peter (2009). "Inner Asia c.1200". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 12–15. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139056045.004. ISBN 9781139056045.

- Abazov, Rafis (2008). Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 43. ISBN 978-1403975423.

- Buniyatov, Z. M. (2015) [1986]. Государство Хорезмшахов-Ануштегинидов: 1097-1231 [A History of the Khorezmian State under the Anushteginids, 1097-1231]. Translated by Mustafayev, Shahin; Welsford, Thomas. Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 978-9943-357-21-1.

- Biran, Michal (2009). "The Mongols in Central Asia from Chinggis Khan's invasion to the rise of Temür". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 47. ISBN 9781139056045.

- Jackson, Peter (2009). "The Mongol Age in Eastern Inner Asia". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 26–45. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139056045.005. ISBN 9781139056045.

- al-Nasawi, Shihab al-Din Muhammad (1241). Sirah al-Sultan Jalal al-Din Mankubirti [Biography of Sultan Jalal al-Din Mankubirti] (in Arabic). p. 13. OCLC 21732074.

- May, Timothy (2018). "The Mongols outside Mongolia". The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9780748642373. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctv1kz4g68.11.

- Juzjani, Minhaj-i Siraj (1260). Tabaqat-i Nasiri طبقات ناصری (in Persian). Vol. XXIII. Translated by Raverty, H. G. p. 968.

- al-Din, Rashid (c. 1300). Thackston, W. M. (ed.). Jami' al-tawarikh جامع التواريخ [Compendium of Chronicles] (in Arabic and Persian). Vol. 2. p. 346.

- Rossabi, Morris (October 1994). "All the Khan's Horses" (PDF). Natural History: 49–50. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Smith, John Masson (1975). "Mongol Manpower and Persian Population". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 18 (3): 273–4, 280–4. doi:10.2307/3632138.

- Sverdrup, Carl (2010). France, John; J. Rogers, Clifford; DeVries, Kelly (eds.). "Numbers in Mongol Warfare". Journal of Medieval Military History. Boydell and Brewer. VIII: 109–117. ISBN 9781843835967. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt7zstnd.6. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Owen, David (2009). The Little Book of Warfare: 50 Key Battles That Trace The Evolution Of Conflict. Fall River Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9781741109139.

- McLynn, Frank (2015). Genghis Khan: His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy. Hachette Books. OCLC 1285130526.

- Barthold, Vasily (1968) [1900]. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion (Third ed.). Gibb Memorial Trust. OCLC 4523164.

- Sverdrup, Carl (2013). "Sübe'etei Ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist". Journal of Asian History. Harrassowitz Verlag. 47 (1): 37. doi:10.13173/jasiahist.47.1.0033. JSTOR 10.13173/jasiahist.47.1.0033.

- Juvaini, Ata-Malik (c. 1260). Tarikh-i Jahangushay تاریخ جهانگشای [History of the World Conqueror] (in Persian). Vol. 1. Translated by Andrew Boyle, John.

- Sverdrup, Carl (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Campaigns of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. Helion & Company. pp. 151–3. ISBN 978-1913336059.

- Martin, H. Desmond (1943). "The Mongol Army". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 75 (1–2): 46–85. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00098166.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). "The Career of the Great Khan Chinggis". Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. p. 422. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1cbn3m5.21. ISBN 9780674445154. JSTOR j.ctv1cbn3m5.21.

- D. Buell, Paul (1979). "Sino-Khitan Administration in Mongol Bukhara". Journal of Asian History (2 ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. 13 (2): 130–131. JSTOR 41930343.

- Hill, D.R. (2000). "10: Physics and Mechanics; Civil and Hydraulic Engineering; Industrial Processes and Manufacturing; and Craft Activities". In Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, M.S. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV / #2. UNESCO Publishing. p. 262. ISBN 9231034677.

- Starr, S. Frederick (2013). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-691-15773-3.

- Uysal, Muzaffer; Kantarci, Kemal; Magnini, Vincent P. (September 2014). "Bukhara: The Princess of Cities". Tourism in Central Asia. Apple Academic. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-1774633663.

- Chalind, Gérard; Mangin-Woods, Michèle; Woods, David (2014). "Chapter 7: The Mongol Empire". A Global History of War: From Assyria to the Twenty-First Century (First ed.). University of California Press. pp. 144–145. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt7zw1cg.13.

- Foltz, Richard (2019). A History of the Tajiks: The Iranians of the East. I.B. Tauris. p. 94. ISBN 978-1784539559. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Chih'ch'ang, Li (1935). Kuo-Wei, Wang (ed.). Hsi-yu chi [Record of a Pilgrimage to the West]. p. 327.

- May, Timothy (2019). "The Rise of Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Empire". The Mongols. Amsterdam University Press. p. 39. doi:10.1017/9781641890953.002. ISBN 9781641890953. S2CID 240850353.

- Blair, S. (2000). "13: Language Situation and Scripts (Arabic)". In Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, M.S. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV / #2. UNESCO Publishing. p. 347. ISBN 9231034677.