Shelby Gem Factory

ICT Incorporated, operating under the trade name the Shelby Gem Factory, was a Michigan company that manufactured artificial gemstones through proprietary processes. The factory made more varieties of man-made gemstones than any other in the world.[1][2] [3][4][lower-alpha 1] It grew artificial gems and gem simulants, including synthetic ruby and sapphire and simulated diamonds,[2][7] citrine, topaz, and other birthstone substitutes, and mounted them in gold or silver jewelry.

Shelby Gem Factory factory | |

| Shelby Gem Factory | |

| Type | Private |

| Founded | 1970 |

| Founders |

|

| Defunct | 2019 |

| Headquarters | , United States |

| Owners |

|

| Website | shelbygemfactory.com |

History

ICT Incorporated, trade name "Shelby Gem Factory", is sited in Shelby, on the west coast of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.[8] It was founded in 1970 by Larry Paul Kelley, Tom VanBergen, and Craig Hardy.[2][7][9] Their building was the first built in the new Shelby Industrial Park. They started with a small core team of people that worked the furnaces around the clock for three to four weeks that produced a crystal large enough to work with to produce small individual gemstones. As the business grew with increased sales, they added additional furnaces and more employees to work them. Over a span of 50 years, they employed over 100 people.[10]

Specialized equipment that was needed for the production of gemstones was handmade in a machine shop across the street by Larry's brother.[10] Larry and his wife Jo later retained full ownership making the Shelby Gem Factory a family business.[11][12][13] The Shelby Gem Factory initially produced only synthetic ruby, with ruby lasers being the principal application, primarily sold to firms in California. However, the greater profit potential of converting ruby rods into a variety of artificial gemstones of various colors led to a change in the factory's focus. In most cases the price of an artificial gemstone they produced was about 1 to 2 percent of the price of a real stone that was mined.[10]

A colorless variant crystal was developed by experimentation with different materials.[9] This was the first simulated diamond variety of manufactured gemstones.[4] The Shelby Gem Factory became the first business anywhere to mass-produce a cubic zirconia (CZ) simulated diamond. In the 1970s the Shelby Gem Factory rode the wave of popularity that CZ then enjoyed; at its peak, tons of cubic zirconia simulated diamonds were produced for the world market. Shelby opened factories in France, China, India, Thailand, and Panama to keep up with demand.[7]

Factory

Formerly, factory tours were offered.[14][15][16] However, they were discontinued due to liability concerns attendant to the "very high temperatures and extremely bright light" and the unavailability of affordable insurance to cover the risk.[4] Some of the furnaces burned at 5,040 °F (2,780 °C).[14]

The factory included a museum, showroom, and theater, and was a popular destination for schools, venture tours, and lapidary clubs. The 50-seat Art and Science theater showed visitors the differences between the processes that produce natural and man-made gems.[3] Exhibits on-site included a lapidary machine visitors can try out for themselves to learn about gem cutting and a low-temperature model of a working crucible-furnace, along with photos of the factory floor which was, by then, off-limits.[4]

The public could purchase gemstone jewelry from the factory.[9] Jo Kelley, wife of Larry Paul Kelley, attributed the factory's increase in sales between 2008 and 2010 to the weak national economy.[17] [18][19]

Gem manufacturing

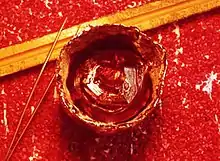

The gems were synthesized in a furnace. It used a US$85,000 heat resistant iridium[4] crucible heated by surrounding electric coils and produced temperatures ranging from 3,500 to 5,000 °F (1,930 to 2,760 °C). A crystal-producing mix was put into this furnace and melted. Then a slowly-spinning rod, the "seed", was lowered into the crucible, circulating the molten minerals, creating a homogeneous mixture and maintaining an even temperature throughout. Raised slowly over the course of weeks, the rotating rod cooled the liquid and allowed a large crystal to form. It took several weeks to grow a gem crystal that would be made into several small artificial gems.[17]

The factory did not use the Verneuil method of "pulling" crystals, using temperature differences like the process that forms an icicle. Rather, it used small fragments of mined gems, which were then used as seeds to re-crystallize liquid into larger gemstones. This is the so-called Czochralski process, which is akin to chemical vapor deposition. Larry Kelley believed that his firm was the only company in the world to use this method.[4]

Shelby Gem Factory workers then cut several dozen rough gems from each crystal using a diamond saw. A rough gemstone piece was placed onto a faceting machine, where over fifty facets were cut and polished to create a finished gemstone.[17] ICT had a master jeweler on staff to mount the finished gemstones in gold settings; Larry Kelley purchased rough gold castings from out of state, and finished these at the factory to make settings as needed.[17] The crystals made by the Shelby Gem Factory were used in jewelry and scientific industries worldwide. Unlike naturally-produced stones, these products were free of occlusions and internal and external flaws or inclusions.[20]

The Shelby Gem Factory's simulated diamonds were diamond simulants, which are not to be confused with lab-grown synthetic diamonds. However, they can be difficult to distinguish from real diamonds.[9] They have a D color rating, the highest rating for diamonds (as determined by the Gemological Institute of America).[lower-alpha 2] Although some of the company's products were "simulants", their synthetic ruby and sapphire stones were not imitations; they had the same chemical and crystalline structure that is found in natural stones. The Shelby Gem Factory also manufactured simulated citrine and topaz, along with other birthstone substitutes.[4]

As per the company website's FAQ section in 2017,[21] these were the Mohs scale hardness values for some well-known gems along with Shelby gem products:

- Genuine diamond, 10

- Shelby simulated diamond ("Diamond Encore"), 8-7/8

- Genuine emerald and aquamarine, 7.5-8.0

- Shelby simulated emerald and aquamarine, 8.6

- Genuine garnet, 6.0

- Shelby-made garnet, 8.6

The company's policy was to maintain the confidentiality of celebrity clients, of whom there were many.[1]

Demise

The factory closed in 2019, after 50 years of manufacturing. Larry Kelley, the founder and main engineer, was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 2017; this made him unable to continue running the business of manufacturing and selling artificial gemstones. Other issues that contributed to the closing were worldwide competition and online markets.[22]

See also

Notes

- The company website says "We...are the only company in the world that...makes uncut gems, facets them, [and] mounts them in gold..."[5][6]

- Larry Kelley also makes the claim that it is impossible to distinguish a Shelby simulated diamond from a natural one using only the naked eye. See Crystallographic defects in diamond.[2]

References

- Burcar, Colleen (October 2, 2012). Michigan Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff (3rd ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, Globe Pequot Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7627-9067-8. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- Zoladz, Chris (February 14, 2013). "Made in Michigan: The Shelby Gem Factory". Lakeshore News Top Headlines. WZZM television station. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

The company makes a wider variety of gem stones than any other company in the world.

- "Shelby Man-Made Gemstone Factory". Pure Michigan. Michigan Economic Development Corporation. 2015. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

The factory...in operation since 1970...makes more varieties of Man-Made Gemstones than any other company in the World.

- Kates, Kristi (December 31, 2012). "A Flaming Success at the Shelby Gem Factory". Northern Express. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- "Shelby Gem Factory Home page". Shelby Gem Factory. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "West Michigan Works: A visit with Shelby Gem Factory" (Video). Mason County Press. June 19, 2015. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "Shelby Gem Factory celebrates 40 years". Oceana's Herald-Journal. December 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- Albrecht, Julie (March 31, 2007). Traveling Michigan's Sunset Coast (Paperback). Dog Ear Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-59858-321-2. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- Rohan, Barry (September 18, 1992). "Success glitters: Firm shines at producing gem substitutes". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. p. 1E, 2E. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hallack, Sharon (December 9, 2019). "Getting their sparkle on for 50 years". Oceana's Herald-Journal. Shelby, Michigan. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- Keefer, Melissa (February 7, 2015). "Shelby Gem owners love using science to create beauty". Ludington Daily News.

- Pohlen, Jerome (May 1, 2014). Oddball Michigan: A Guide to 450 Really Strange Places (Paperback). Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-61374-896-1. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "A Flaming Success at the Shelby Gem Factory". Northern Express. December 30, 2012. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- DeZutter, Hank; DeZutter, Pamela Little (June 3, 1993). "Idlewild, Michigan: These Parts". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- Bonstell, Christy L. (August 2, 2008). "Factory tours take you behind the scenes and satisfy your curiousity [sic]". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Michigan Living, AAA Michigan". 75. Automobile Club of Michigan. 1993: 20. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tableman, Jan (2011). "Jewel of West Michigan: Shelby Gem Factory". Michigan Country Lines. Okemos, Michigan: Michigan Electric Cooperative Association: 1, 3, 10–11.

- Burcar, Colleen; Taylor, Gene (2003). Michigan: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities and Other Offbeat Stuff (Paperback). Globe Pequot Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7627-0601-3.

- "Jewelers' Circular/keystone '77 Directory". 150 (1–5). Chilton Company. 1979: 92. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Heim, Michael (January 1, 2004). Exploring America's Highways: Michigan Trip Trivia (Paperback). Wabasha, Minnesota: Travel Organization Network Exchange (T.O.N.E. Publications). p. 170. ISBN 978-0-9744358-2-4.

- "FAQs". Shelby Gem Factory. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "Shelby Gem Factory to close". Oceana County Press. December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shelby Gem Factory. |