Sandy Creek Expedition

The Sandy Creek Expedition, also referred to as the Sandy Expedition or sometimes the Big Sandy Expedition,[1] (not to be confused with the Big Sandy Expedition of 1851) was a 1756 campaign of Virginia soldiers and Cherokee warriors into what is now western West Virginia, against Shawnee warriors who were raiding Virginia farms and settlements. The campaign set out in mid-February, 1756, and was immediately slowed by harsh weather and inadequate provisions. With morale failing, the expedition was forced to turn back in mid-March without encountering the enemy.

| Sandy Creek Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Shawnee | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Major Andrew Lewis Outacite Ostenaco | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Virginia Regiment Cherokee | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 340 (four units Virginia infantry and 130 Cherokee warriors) | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| killed: 2 | |||||||

The expedition was the first allied military campaign between the British and the Cherokees against the French and their allied Native Americans during the French and Indian War.[2]

Background

_(NYPL_Hades-256493-EM14797).tiff.jpg.webp)

The defeat of General Edward Braddock at the Battle of the Monongahela in July, 1755, left the Colony of Virginia without a professional military force. Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie decided to form several "ranging companies" to protect settlements from attacks by Native tribes allied with the French. These volunteer ranger units, intended as a defensive force, built and garrisoned forts and reinforced areas expecting attack.[3] The only offensive action of the Virginia Rangers during the French and Indian War was the Sandy Creek Expedition.[4][5]

The campaign was initiated by Virginia's governor in response to Indian raids on settlements in the New River, Greenbrier River, and Tygart River valleys,[6]: 62 during which about 70 settlers were killed, wounded, or captured.[7] Farms and communities were abandoned as survivors retreated east into the Shenandoah Valley. In June, 1755, Shawnee warriors captured Captain Samuel Stalnaker at his homestead on the Holston River, (near present-day Chilhowie, Virginia), and killed his wife and son.[8] In July, Mary Draper Ingles and her children were captured during the Draper's Meadow Massacre, (near present-day Blacksburg, Virginia). Both later escaped captivity and walked hundreds of miles to return home.[9]: 149 After arriving home in November, 1755, Mary Draper Ingles probably informed her husband William Ingles of the general location and layout of Lower Shawneetown, where she had lived as a captive for about three weeks. William Ingles may have suggested to Governor Dinwiddie the idea for an attack on this large Native American community.[10]: 22 Stalnaker was also held at Lower Shawneetown, where Mary Ingles met him and other captives taken in settlement raids. He escaped in May, 1756.[8]

In retaliation against the Shawnee raids, Governor Dinwiddie sent a company of Virginia regulars, a company of minutemen, two companies of Volunteer Rangers (Preston refers to six companies in total), and 130 Cherokee warriors to attack Lower Shawneetown, which was the main Shawnee community at the confluence of the Ohio River and the Scioto River. Colonel George Washington (then in command of the Virginia Regiment) selected Major Andrew Lewis to lead the expedition.[6][11]: 218–223

Role of the Cherokees

Cherokee leaders had recently been trying to improve trade relations with the Virginia colonial government, and had petitioned Governor Dinwiddie for some assistance in the long-delayed construction of a fort in South Carolina, to protect Cherokee communities from raids by French-allied Shawnee and Catawba Indians.[2] Dinwiddie financed the construction of the fort, and in return the Cherokees sent 130 warriors to Fort Frederick to support the Sandy Creek Expedition.

On 14 December 1755, the governor wrote to Colonel Washington:

- "The Cherokees have taken up the Hatchet against the French & Shawnesse, & have sent 130 of their Warriors to New River, & propose to march immediately to attack, & cut off the Shawnesse, in their Towns. I design they shall be join’d with three Companies of Rangers, & Capt. Hogg’s Company, & I propose Colo. Stephens or Majr. Lewis to be the Commander of the Party on this Expedition."[12]

The Cherokee warriors were under the joint leadership of Captain Richard Pearis and Chief Outacite Ostenaco. Dinwiddie had agreed to supply them with guns and ammunition, but could only obtain older, heavier rifles for the Cherokees, writing on 15 January, 1756: "I have sent 150 Small Arms, Powder and Shott...I know they are too heavy but I have desired they may have the lightest [that] are among our people..."[13]: 324

The Cherokees offered to train Virginian soldiers in Indian-style warfare, which favored shooting from behind cover, using stealth and surprise, rather than firing in volleys from assembled ranks. Washington wanted Virginian troops to adopt these tactics,[14] and noted,

- "...five hundred Indians have it more in their power to annoy the Inhabitants, than ten times their number of Regulars. For, besides the advantageous way they have of fighting in the Woods, their cunning and craft are not to be equalled; neither their activity and indefatigable Sufferings: They prowl about like Wolves; and like them, do their mischief by Stealth...It is in their power to be of infinite use to us; and without Indians, we shall never be able to cope with those cruel Foes to our Country..."[15]

On 13 January, 1756, Washington wrote to Dinwiddie: "I have given all necessary orders for training the Men to a proper use of their Arms, and the method of Ind'n Fighting, and hope in a little time to make them expert."[16][17]: 286 Dinwiddie approved, writing to Washington on 23 January: "You have done very right in ordering the Men to be train'd in the [Indian] Method of fighting..."[13]: 325 [18] The Virginians also needed to learn woodcraft and the art of tracking enemies through the wilderness. The son of the Cherokee chief Conocotocko I commented to Dinwiddie: "Our brothers [the Virginians] fight very strong, but can’t follow an Indian by the Foot as we can."[13]: 188

Timing and route

Major Lewis decided not to use the shorter and easier route to Lower Shawneetown, which would have been along the New River to the Kanawha River, because he was afraid the Shawnee would be more likely to learn about the expedition. Instead, he chose a less-traveled route through uninhabited mountains,[10]: 23 following a war trail along "Sandy Creek," (now known as the Dry Fork), then following the Tug Fork to the Big Sandy River that forms the West Virginia-Kentucky border today. The expedition passed through present-day McDowell County and Mingo County. The decision to launch the expedition in February was based on the assumption that the Big Sandy would be swollen by snowmelt, making it easier and faster to descend by canoe.[2]: 41 Also, Washington apparently had received intelligence indicating that many of Lower Shawneetown's warriors had "removed up the River, into the Neighbourhood of [Fort] Duquesne," leaving the town temporarily defenseless.[17]: 286

Expedition

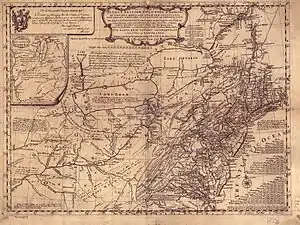

On 6 February, 1756, Dinwiddie wrote to Lewis: "The distance by Evans' map[19] is not two hundred miles to the Upper Towns of the Shawnees, however, at once begin your march."[13]: 332

On 9 February, the Virginians assembled at Fort Prince George, near Roanoke, Virginia[11] and marched to meet the Cherokees at the newly built Fort Frederick on the New River. They brought with them over two thousand pounds of dried beef, intended as provisions for the campaign. Among the troops was Lieutenant William Ingles, husband of Mary Draper Ingles, and Captain William Preston, both survivors of the Draper's Meadow Massacre. On 19 February the full contingent of 340 men and 27 pack horses set out, crossing over the north fork of the Holston River and camping on 23 February at Burke's Garden.[7]

The Cherokees, led by Outacite Ostenaco, were accustomed to the rugged terrain and the exertion necessary for wilderness warfare, unlike most of the Virginians, who never fought a winter campaign in the mountains. Cutting trails through the thickly-forested valleys, scaling steep slopes, and crossing rivers and creeks repeatedly was slow and exhausting due to harsh weather and streams swollen with snowmelt and rain. They reached the headwaters of the Big Sandy River on 28 February, where Captain William Preston wrote:

- “Saturday 28th We marched 10 oClock & passed several branches of Clinch and at length got to the head of Sandy Creek where we met with great trouble & fatigue occasioned by a very heavy rain and the driving of our baggage horses down sd Creek which we crossed 20 times that evening.”[20]

On 29 February, Captain Preston wrote in his journal: "The creek has been much frequently used by Indians both traveling and hunting on it, and...I am apprehensive that Stalnaker and the prisoners taken with him were carried this way."[11]: 210

During the first weeks the troops supplemented their rations with bear meat, deer, and buffalo.[11] They gathered potatoes from abandoned gardens. However, within a few days flour and dried beef ran short and rations were cut by half. By 3 March, the last of the corn brought to feed the horses was gone. The men hunted, but the few deer and elk they killed were insufficient to feed 340 troops. Lewis suggested that they slaughter and eat their horses, but the men refuused.[21] The weather was extremely cold and snow made progress even slower. Lieutenant Thomas Morton, who kept a diary of the expedition, wrote:

- "...In our Camps was little else but cursing, swearing, confusion and complaining...and we are now suf'ring very much for want of provision, and a great part of the men...have this day fallen on a resolution to go back, for we can see nothing before us but inevitable destruction."[22]: 143–147

The expedition paused on 7 March to build canoes, with the hope that traveling by water would be less tiresome. Captain Preston estimated that by 8 March they had traveled 186 miles.[10]: 29 On 12 March, an accident led to the loss of guns and tents. Captain Preston wrote in his diary for that day:

- "Capt. Woodson now arrived with some of his company, with the intelligence that his canoe overset, and he had lost his tents, and every thing valuable in it; that Major Lewis' canoe was sunk in the river, and that the Major, Capt. Overton, Lieut. Gun, and one other man had to swim for their lives, and that several things of value were lost, particularly five or six fine guns."[7]

Rations were by now nearly exhausted and men began to desert, trying to make their way home in small groups, most of whom did not survive. On 13 March, Lewis asked which of his troops were willing to continue, but only a small number voted to proceed. Two companies had already decided to turn back, and Lewis himself was finally forced to make the decision to abandon the campaign and return home. Preston's diary ends with:

- "Then Major Lewis stepped off some yards, and desired all who were willing to serve their country and share his fate, to go with him. All the officers, and some of the privates, not above twenty or thirty, joined him; upon which Montgomery's volunteers marched off, and were immediately followed by Capt. Preston's company, except the Captain, his two Lieutenants, and four privates...Major Lewis spoke to old Outacité, who appeared much grieved to see the men desert in such a manner, and said he was willing to proceed; but some of the warriors and young men were yet behind, and he was doubtful of them...The old chief added, that the white men could not bear abstinence like the Indians who would not complain of hunger."[7]

Aftermath

Alexander Scott Withers (using material from Hugh Paul Taylor) says that on the way home, the troops were attacked by Shawnee warriors on 15 March and two soldiers were killed. Lieutenant McNutt then proposed that they proceed to Lower Shawneetown and complete their mission, in hopes of capturing the town and getting food there, but Major Lewis decided to continue home. They had to kill their pack horses for food and at one point were forced to eat boiled leather and buffalo hide.[6]

The troops arrived in Winchester, Virginia, on 7 April[7] and later returned to Fort Frederick. On 7 April George Washington wrote to Dinwiddie:

- "I doubt not but your honor has had a particular account of Maj. Lewis's unsuccessful attempt to get to the Shawanese town. It was an expedition from which, on account of the length of the march, I always had little hope, and often expressed my apprehensions."[15]

Lieutenant Thomas Morton noted:

- "Major Lewis's party suffered greatly on this expedition. The rivers were so much swoln by rains and melting snow that they were unable to reach the Shawanese town, and after six weeks in the woods, having lost several Canoes with provisions and ammunition, they were reduced nearly to a state of starvation, and obliged to kill their horses for food."[22]

Major Lewis was subsequently cleared of any fault in the expedition's failure.[23] A second Sandy expedition seems to have been contemplated, but for some reason abandoned.[10]: 30

Lower Shawneetown was moved upriver to the Pickaway Plains in 1758 because the Shawnees were, in George Croghan's words, in "fear of the Virginians."[24] It remains unclear whether the Shawnees learned of the expedition and feared that eventually the town would be attacked, or whether recurrent floods threatened the community.

The Sandy Creek Expedition was clearly a failure, but it served as valuable experience for Andrew Lewis, William Preston, and others who would defend Virginia during the French and Indian War and in the American Revolution. Preston's Rangers would continue to serve until May, 1759.[4][5] The campaign forged closer ties between the Cherokee people and the Virginia colonial government.[2][16][25]

Sources

Only two primary sources describing the expedition exist, the diary of Captain William Preston, published in 1906,[10]: 24–29 and a fragment of Lieutenant Thomas Morton's diary, published in 1851.[22] There are some references to the expedition in the correspondence of Governor Dinwiddie and George Washington, but no final report to the Virginia House of Burgesses by Major Andrew Lewis exists.[10]: 30 Alexander Scott Withers states that "a journal of this campaign was kept by Lieut. Alexander McNutt...On his return to Williamsburg he presented it to Lieutenant-Governor Francis Fauquier by whom it was deposited in the executive archives," but it appears to have been lost.[6] Withers' account of the expedition seems to have been partly based on Taylor's Historical Sketches of the Internal Improvements of Virginia (1825, now lost) and on an article Taylor published under the pseudonym "Son of Cornstalk" in the Fincastle Mirror in 1829, and has a number of significant errors.[26]

Memorialization

In 2015 a driving tour following the route of the Sandy Creek Expedition was developed by Trails, Inc.[20] The route starts on the Virginia-West Virginia border and passes through Vallscreek to Canebrake, Berwind, and into the Berwind Wildlife Management Area to Excelsior, Raysal, and Wyoming City, finishing at Wharncliffe. The tour includes ten points of interest as well as campsites.[27]

See also

External links

- Douglas McClure Wood, “I Have Now Made a Path to Virginia”: Outacite Ostenaco and the Cherokee-Virginia Alliance in the French and Indian War"

- "March 13, 1756: Sandy Creek Expedition Comes to a Halt," West Virginia Public Broadcasting, West Virginia Encyclopedia, March 13, 2019 at 7:00 AM EDT

- "Sandy Creek Expedition," West Virginia Encyclopedia

- Preston's Rangers, the Ranger company organized by William Preston

- Sandy Creek Expedition Driving Tour Map

References

- Andrew Cayton, Fredrika J. Teute, eds. Contact Points: American Frontiers from the Mohawk Valley to the Mississippi, 1750-1830. Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Douglas McClure Wood, "I Have Now Made a Path to Virginia": Outacite Ostenaco and the Cherokee-Virginia Alliance in the French and Indian War," West Virginia History, New Series, Vol. 2, No. 2 (FALL 2008), pp. 31-60. West Virginia University Press

- Virginia Regiments in the Continental Army, American Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783

- Preston's Rangers

- "The Virginia Ranger Companies, 1755-1763," History Reconsidered

- Alexander Scott Withers, Chronicles of Border Warfare, A History of the Settlement by the Whites, of North-Western Virginia, and of the Indian Wars and Massacres in that section of the State, Cincinnati: The Robert Clarke Company, 1895

- Lyman C. Draper, "The expedition of the Virginians against the Shawanoe Indians, 1756," Virginia Historical Register and Literary Companion, Vol. V, Number II. Richmond: McFarlane & Fergusson, April 1852

- "Captain Samuel Stalnaker, Colonial Soldier and Early Pioneer," excerpted from Leo Stalnaker, Captain Samuel Stalnaker, Colonial Soldier and Early Pioneer and Some of His Descendants, 1938.

- William Henry Foote, Sketches of Virginia: Historical and Biographical, Vol. 2; William S. Martien, 1855.

- Johnston, David Emmons. A History of Middle New River Settlements And Contiguous Territory, chapter 2. Huntington: Standard Printing & Publishing Co., 1906

- Pendleton, William Cecil, "Chapter V: The Sandy Expedition," in History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia: 1748-1920. W. C. Hill printing Company, 1920.

- "To George Washington from Robert Dinwiddie, 14 December 1755," Founders Online, National Archives. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 2, 14 August 1755 – 15 April 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 213–216.

- Brock, R. A., Dinwiddie, R. The official records of Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1751-1758. Richmond, Va.: The Society.

- George Washington, “Remarks, 1787–1788,” Founders Online, National Archives. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 5, 1 February 1787 – 31 December 1787, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997, pp. 515–526.

- “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 7 April 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 2, 14 August 1755 – 15 April 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 332–336.

- Doug Wood, "Cherokees At The Potomac Forts," The Fort Edwards Web Page, The Fort Edwards Foundation of Capon Bridge, West Virginia, 2008

- George Washington, David Maydole Matteson, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931

- “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 13 January 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 2, 14 August 1755 – 15 April 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 278–281.

- The "Evans-Pownall" map of eastern North America, circa 1755

- How the Sandy Creek Expedition changed history

- "Sandy Creek Expedition," West Virginia Encyclopedia

- "Morton's Diary," in William Maxwell, ed. The Virginia Historical Register, and Literary Note Book. Vol. 3, Richmond: McFarlane & Fergusson, 1850.

- "March 13, 1756: Sandy Creek Expedition Comes to a Halt," West Virginia Public Broadcasting, West Virginia Encyclopedia, March 13, 2019 at 7:00 AM EDT

- Wheeler-Voegelin, Erminie (1974). "An Ethnohistorical Report on the Indian Use and Occupancy of Royce Area 11, Ohio and Indiana". Indians of Ohio and Indiana Prior to 1795. By Wheeler-Voegelin, Erminie; Tanner, Helen Hornbeck. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 378–80. ISBN 0-8240-0798-0.

- Lasting impact of the Sandy Creek Expedition

- David Scott Turk, "Hugh Paul Taylor, Historian and Mapmaker," West Virginia History, Volume 56 (1997), pp. 43-55

- Sandy Creek Expedition Driving Tour Map