SARS-CoV-2 in white-tailed deer

Blood samples gathered by USDA researchers in 2021 showed that 40% of sampled white-tailed deer demonstrated evidence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, with the highest percentages in Michigan, at 67%, and Pennsylvania, at 44%.[1] A later study by Penn State University and wildlife officials in Iowa showed that up to 80 percent of Iowa deer sampled from April 2020 through January 2021 had tested positive for active SARS-CoV-2 infection, rather than solely antibodies from prior infection. This data, confirmed by the National Veterinary Services Laboratory, alerted scientists to the possibility that white-tailed deer had become a natural reservoir for the coronavirus, serving as a potential "variant factory" for eventual retransmission back into humans.[2]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

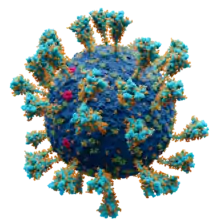

Scientifically accurate atomic model of the external structure of SARS-CoV-2. Each "ball" is an atom. |

|

|

|

In a March 2022 joint statement regarding animal monitoring, the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) specifically cited white-tailed deer as an example of a newly formed wild animal reservoir.[3]

Transmission

Infected deer can shed virus via nasal secretions and feces for 5-6 days and frequently engage in activities conductive to viral spread, such as sniffing food intermingled with waste, nuzzling noses, polygamy, and the sharing of salt licks.[4] Similar to the course of infection in humans, SARS-CoV-2 develops and replicates within the upper respiratory tract of deer, with a particular focus on nasal structures. Infection was also noted within the tonsils, lymph nodes, and central nervous system tissue of deer.[5]

Captive cervid facilities, where deer are kept in close proximity for breeding stock or for hunting, have showcased extremely high levels of transmission, with active infection levels exceeding 90% in one facility.[6]

Although white-tailed deer possess a similar ACE2 receptor to humans that are at risk from SARS-CoV-2, European deer species, such as roe deer, red deer, and fallow deer, that likewise possess this cellular-level susceptibility had not showcased any cases of current or past infection during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. European test data has suggested that the high density of white-tailed deer populations in North America and frequent human interactions are the unique factors which have led to outbreaks throughout the United States and Canada.[7]

Mutations and Variants

A 2021 Ohio State University study showed that humans had transmitted SARS-CoV-2 to white-tailed deer on at least six separate occasions and that the deer in their study possessed six mutations that were uncommon in humans at the time.[8]

Test data from Pennsylvania showed that genomes from a divergent Alpha variant strain had been found within white-tailed deer in November 2021, long after it had ceased to be the dominant strain in humans. This suggested that the Alpha variant had continued to evolve independently in deer without the need for reinfection through direct or indirect human contact.[7]

A study of New York City's white-tailed deer population on Staten Island, commencing in December 2021, found that wild deer had already contracted the Omicron variant, which had just recently become prevalent in humans. One of the actively infected deer had high preexisting levels of antibodies, suggesting that deer can continually be reinfected with SARS-CoV-2.[9]

Ontario WTD clade

In early 2022, Canadian researchers announced the discovery of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant within a November-December 2021 study of Ontario white-tailed deer, labeling it the "Ontario WTD clade". The new COVID variant had also infected a person who had close contact with local deer, potentially marking the first instance of deer-to-human transmission.[10] The last time that a relative of this viral clade had been seen was 10-12 months prior, within humans and mink, across the international border in Michigan. Researchers believe that the variant arose within an animal host during that time since the mutations of the Ontario WTD clade were highly divergent from circulating strains found within humans, evidencing 76 mutations when compared to the original virus.[11][7]

The ancestral mink-human spillover event in Michigan also showed evidence of animal-to-human transmission, resulting in four human infections that were largely kept from public view upon their discovery late 2020, and only announced by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) several months later, in March 2021. The CDC defended its decision by noting that its findings were not "surprising or unexpected", since similar mink-to-human crossover events had already been documented in Europe.[12]

Related Species

Wildlife officials in Utah announced that a November-December 2021 field study had detected the first case of SARS-CoV-2 in mule deer. Several deer possessed apparent SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, however a female deer in Morgan County had an active Delta variant infection.[13] White-tailed deer, which are able to mate and hybridize with mule deer, have migrated into Morgan County and other traditional mule deer habitats since at least the early 2000s.[14]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to White-tailed deer. |

| Wikispecies has information related to White-tailed deer. |

- Fine Maron, Dina (2 August 2021). "Wild U.S. deer found with coronavirus antibodies". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- Jacobs, Andrew (2 November 2021). "Widespread Coronavirus Infection Found in Iowa Deer, New Study Says". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- "Joint statement on the prioritization of monitoring SARS-CoV-2 infection in wildlife and preventing the formation of animal reservoirs". World Health Organization. 7 March 2022. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Anthes, Emily; Imbler, Sabrina (7 February 2022). "Is the Coronavirus in Your Backyard?". New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Ramanujan, Krishna (22 March 2022). "New study defines spread of SARS-CoV-2 in white-tailed deer". Cornell Chronicle. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- Schattenberg, Paul (25 January 2022). "Are Deer In COVID's Crosshairs?". Texas A&M Today. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Mallapaty, Smriti (26 April 2022). "COVID is spreading in deer. What does that mean for the pandemic?". Nature. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- Bush, Evan (2 January 2022). "Covid is rampant among deer, research shows". NBC News. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- Wetzel, Corryn (11 February 2022). "Discovery of Omicron in New York Deer Raises Concern Over Possible New Variants". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Miranda, Gabriela (3 March 2022). "New COVID variant found in deer shows signs of possible deer-to-human transmission". USA Today. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Goodman, Brenda (2 March 2022). "A highly changed coronavirus variant was found in deer after nearly a year in hiding, researchers suggest". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- Fine Maron, Dina (5 April 2022). "Government documents reveal CDC delayed disclosing likely COVID-19 animal spillover event". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- Harkins, Paighten (29 March 2022). "Utah mule deer is 1st in U.S. to test positive for COVID-19". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Prettyman, Brett (19 October 2008). "Hunting: Whitetail deer influx brings mixed reaction". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022.