Rurik

Rurik of Ladoga (also Ryurik or Rorik;[1] Old East Slavic: Рюрикъ Rjurikŭ, from Old Norse Hrøríkʀ; Belarusian: Рурык; Russian, Ukrainian: Рюрик; c. 824–879), according to the 12th-century Primary Chronicle, was a Varangian chieftain of the Rus' who in the year 862 was invited to reign in Novgorod. The legendary figure is considered to be the founder of the Rurikid dynasty, which ruled Ladoga, Novgorod and ultimately the Kievan Rus' and its successor states, including the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, the Principality of Tver, the Grand Duchy of Vladimir, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Novgorod Republic and the Tsardom of Russia, until the 17th century.[2]

| Rurik | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Novgorod | |

Rurik on the monument "Millennium of Russia" in Veliky Novgorod. | |

| Reign | 862–879 |

| Successor | Oleg |

| Born | c. 824 Scandinavia |

| Died | 879 (aged 54–55) Novgorod, Kievan Rus' |

| Issue | Igor |

| Dynasty | Rurik |

Life

The only surviving information about Rurik is contained in the 12th-century Primary Chronicle written by one Nestor, which states that Chuds, Eastern Slavs, Merias, Veses, and Krivichs "drove the Varangians back beyond the sea, refused to pay them tribute, and set out to govern themselves". Afterwards the tribes started fighting each other and decided to invite the Varangians, led by Rurik, to reestablish order. Rurik came in 860–862 along with his brothers Sineus and Truvor and a large retinue.

According to the Primary Chronicle, Rurik was one of the Rus', a Varangian tribe, likened by the chronicler to Scandinavians and Angles.

Sineus established himself at Beloozero and Truvor at the city of Izborsk. Truvor and Sineus died shortly after the establishment of their territories, and Rurik consolidated these lands into his own territory.

According to the entries in the Radzivil and Hypatian Chronicles[3] under the years 862–864, Rurik’s first residence was in Ladoga. He later moved his seat of power to Novgorod, a fort built not far from the source of the Volkhov River. The meaning of this place name in medieval Russian is 'new fortification', while the current meaning ('new city') developed later.

Rurik remained in power until his death in 879. On his deathbed, Rurik bequeathed his realm to Oleg, who belonged to his kin, and entrusted to Oleg's hands his son Igor, for he was very young. Oleg moved the capital to Kiev (by murdering the then-rulers and taking the city) and founded the state of Kievan Rus', which was ruled by Rurik's successors (his son Igor and Igor's descendants). The state persisted until the Mongol invasion in 1240.

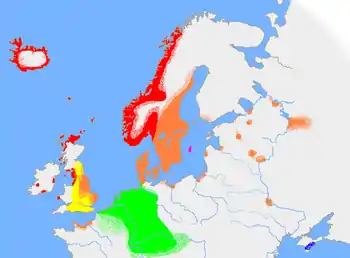

Hypothesis of identity with Rorik of Dorestad

The name Rurik is a form of the Old Norse name Hrœrekr.[4] Rorik of Dorestad was a member of one of two competing families reported by the Frankish chroniclers as having ruled the nascent Danish kingdom at Hedeby. He may have been a nephew of king Harald Klak. He is mentioned as receiving lands in Friesland from Emperor Louis I. He started to plunder neighbouring lands: he took Dorestad in 850, attacked Hedeby in 857, and looted Bremen in 859, while his own lands were ravaged in his absence. The Emperor was enraged and stripped him of all his possessions in 860. After that, Rorik disappears from western sources for a considerable period of time. In 862, according to the Russian sources, Rurik arrived in the eastern Baltic and built the fortress of Ladoga. Later he moved to Novgorod.

Rorik of Dorestad reappeared in Frankish chronicles in 870, when his Friesland demesne was returned to him by Charles the Bald. In 882 Rorik is mentioned as being dead (without a date of death specified). The Russian chronicle places the death of Rurik of Novgorod in 879, three years earlier than the Frankish chronicles. According to western sources, the ruler of Friesland was converted to Christianity by the Franks. This may have parallels with the Christianization of the Rus' reported by Patriarch Photius in 867.

The idea of identifying Rurik of Rus' with Rorik of Dorestad was revived by the anti-Normanists Boris Rybakov and Anatoly H. Kirpichnikov in the mid-20th century,[5] but Alexander Nazarenko and other scholars have objected to it.[6] The hypothesis of their identity currently lacks wide support among scholars,[7] though support for a "Normannic" (Norse rather than Slavic) origin of Rus' has increased.

Folklore

In Estonian folklore there is a tale of three brothers, who were born as sons of a peasant, but, through great bravery and courageousness, all later became rulers in foreign countries. The brothers were called Rahurikkuja (Troublemaker), Siniuss (Blue snake) and Truuvaar (Loyal man) (estonianized names for Rurik and his brothers Sineus and Truvor), names given to them by their childhood friend, a blue snake.[8]

Legacy

The Rurik dynasty (or Rurikids) went on to rule Kievan Rus', and ultimately the Tsardom of Russia, until 1598, and numerous noble families in the former lands of Kievan Rus' claim male-line descent from Rurik. The last Rurikid to rule Russia was Tsar Vasily IV (from the House of Shuysky, cadet branch of the House of Rurik), who reigned till 1612.

References

- HARRIS, ZENA; RYAN, NONNA (2004). "The Inconsistencies of History: Vikings And Rurik". New Zealand Slavonic Journal. 38: 105–130. ISSN 0028-8683.

- Christian Raffensperger and Norman W. Ingham, "Rurik and the First Rurikids", The American Genealogist, 82 (2007), 1–13, 111–119.

- Ipat’ievskaia letopis’ 1962:14; Radzivilovskaia letopis’ 1989:16

- Omeljan Pritsak, "Rus'", in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 555–56.

- Kirpichnikov, Anatoly H. "Сказание о призвании варягов. Анализ и возможности источника". Первые скандинавские чтения, СПб; 1997; ch. 7–18.

- Nazarenko, Alexander. "Rjurik и Riis Th., Rorik", Lexikon des Mittelalters, VII; Munich, 1995; pp. 880, 1026.

- Andrei Mozzhukhin (5 October 2014). «Рюрик — это легенда» ["Rurik – is a legend"]. Russian Planet (in Russian). Retrieved 12 November 2014. Interview with Igor Danilevsky.

- Kampmaa, Mihkel. Majaussi kaswandikud. Tähelepanemise wäärt Eesti muinasjutt. Sakala, no 20, 09.06.1890

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rurik. |

.svg.png.webp)