Royal necropolis of Byblos

The royal necropolis of Byblos is a group of nine underground shaft and chamber tombs housing the sarcophagi of several kings of the city. Byblos, one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world, established major trade links with Egypt during the Bronze Age, leading to the latter heavily influencing local culture and funerary practices. The location of ancient Byblos was lost to history, but was rediscovered in the late 19th century by the French biblical scholar and orientalist Ernest Renan. Exploratory trenches and minor digs were undertaken by the French mandate authorities, during which Egyptian hieroglyph-inscribed reliefs were excavated. The discovery stirred the interest of western scholars, leading to systematic surveys of the site.

| Royal necropolis of Byblos | |

|---|---|

Promontory of the Byblos acropolis. The royal necropolis of Byblos lies at the base of the Roman colonnade. | |

| Location | Jbeil (ancient Gebal, Byblos) |

| Coordinates | 34°07′11″N 35°38′40″E |

| Area | Byblos, Lebanon |

| Founded | 19th century BC |

| Built for | Resting place of the Phoenician Gebalite rulers |

| Architectural style(s) | Ancient Egypt-inspired, Phoenician |

| Governing body | Lebanese Directorate General of Antiquities |

Location of Royal necropolis of Byblos in Lebanon | |

On 16 February 1922, heavy rains triggered a landslide in the seaside cliff of Jbeil, exposing an underground hypogeum containing a massive stone sarcophagus. The grave was explored by the French epigrapher and archaeologist Charles Virolleaud. Intensive digs were carried out around the site of the hypogeum by the French Egyptologist Pierre Montet, who unearthed eight additional shaft tombs. Montet categorized the graves, each of which consisted of a vertical well connected to a horizontal burial chamber at its bottom, into two groups. The tombs of the first group dated back to the Middle Bronze Age, specifically the 19th century BC; some were unspoiled, and contained a multitude of often valuable items, including gifts from Middle Kingdom pharaohs Amenemhat III and Amenemhat IV, and Egyptian-style local crafts. The graves of the second group were all robbed in antiquity making precise dating problematic, however, the artifacts indicate that some of the tombs were used into the Late Bronze Age (16th to 11th centuries BC).

In addition to grave goods, seven stone sarcophagi were discovered—the burial chambers that did not contain stone sarcophagi would have housed wooden ones which have disintegrated over time. The stone sarcophagi were undecorated, save the Ahiram sarcophagus. This sarcophagus is famed for its Phoenician inscription, one of five epigraphs known as the ‘Byblian royal inscriptions’; it is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet. Montet compared the function of the Byblos tombs to that of Egyptian mastabas, where the deceased was believed to take the form of a bird and fly from the burial chamber and the funerary well to the ground-level chapel where priests officiate.

Historical background

Byblos (modern Jubayl) is one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty Egyptian hieroglyphic records, and as Gubla (𒁺𒆷) in the Akkadian cuneiform Amarna letters of 18th-dynasty-Egypt.[1][2][3] In the second millennium BC, its name appeared in Phoenician inscriptions, such as the Ahiram sarcophagus epitaph, as Gebal (𐤂𐤁𐤋, GBL),[4][5][6] which derives from GB (𐤂𐤁, "well"), and ʾL (𐤀𐤋, "god"). The name thus seems to have meant the "Well of the God".[7] Another interpretation of the Gebal is "mountain town", derived from the Canaanite Gubal.[8]

The ancient settlement sat on a plateau immediately abutting the sea that has been inhabited, and continuously used since as early as 7000–8000 BC.[9] Simple, circular and rectangular habitation units and jar burials dating from the Chalcolithic were unearthed in Byblos. The village grew during the Bronze Age, and became a major center for trade with Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Crete, and Egypt.[10][11]

Egypt sought to keep control of Byblos because of its need for lumber, abundant in the mountains of Lebanon.[10] During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2686 BC–c. 2181 BC), Byblos came under Egyptian control. The city was destroyed by the Amorites around 2150 BC, in the aftermath of the power vacuum that ensued after the fall of the Old Kingdom.[10][11] However, with the emergence of Egypt's Middle Kingdom (c. 1991 BC–c. 1778 BC), Byblos' defensive walls and temples were rebuilt, and it came once more under Egyptian hegemony.[10][11]

In 1725 BC, The Egyptian Delta and coastal cities of Phoenicia fell to the Hyksos as the Middle Kingdom disintegrated. A century and a half later, Egypt expelled the Hyksos and returned Phoenicia under its fold, and effectively defended it against the Mitanni and Hittite invasions.[10][11] During this period, Gebalite[lower-alpha 1] trade flourished, and the first phonetic alphabet was developed in Byblos.[11] It consisted of 22 consonant graphemes that were simple enough for common traders to use.[11][14][15]

Relation with Egypt dwindled again in the mid 14th–century, as attested in the Amarna correspondence with the Gebalite king Rib-Hadda. The letters reveal the inability of Egypt to defend Byblos and its territories against Hittite incursion.[10][11][16]

During the time of Ramses II, Egyptian hegemony over Byblos was restored; nevertheless, the city was destroyed soon after by the Sea Peoples around 1195 BC. Egypt was weakened during this time, and consequently, Phoenicia experienced a period of prosperity and independence. The Story of Wenamun, which is contemporaneous to this period, shows the continued, yet tepid relations between the Gebalite ruler and the Egyptians.[10]

Longstanding relations with Egypt heavily influenced local culture and funerary practices. It is during periods of Egyptian overlordship that the practice of Egypt-inspired shaft burials appeared.[17]

Excavation history

The search for the ancient city

Ancient texts and manuscripts hinted to the location of Gebal, which was lost to history until the advent of the 19th century. In 1860, French biblical scholar and orientalist Ernest Renan carried out an archaeological mission in Lebanon and Syria during the French expedition in the area. Renan had relied on Strabo's writing in his attempt to locate the city. Strabo identified Byblos as a city situated on a hill some distance away from the sea.[lower-alpha 2][19][20] This description misled scholars, including Renan who thought that the city lay in the neighboring Qassouba (Kassouba), but he concluded that this hill was too small to have housed a grand ancient city. Renan correctly posited that the Ancient Byblos must have been located atop the circular hill dominated by the Crusader citadel of Jbeil. Starting from the citadel, he had two long trenches dug; the trenches revealed ancient artifacts unquestionably demonstrating that Jbeil is the same as the ancient city of Gebal/Byblos.[19][20]

Early archaeological works

During the period of French Mandate, High Commissioner General Henri Gouraud established the Service of Antiquities in Lebanon; he appointed French archaeologist Joseph Chamonard to head the newly created service. Chamonard was succeeded by French epigrapher and archaeologist Charles Virolleaud as of 1 October 1920. The service prioritized archaeological surveys in the town of Jbeil where Renan had found ancient remains.[21]

On 16 March 1921, Pierre Montet, the Egyptology professor at the University of Strasbourg, addressed a letter to notable French archaeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau describing Egyptian-inscribed reliefs he had discovered during a 1919 archaeological mission in Jbeil. The fascinated Clermont-Ganneau personally funded the methodological survey of the site, which he believed contained an Egyptian temple. Montet was selected to head the excavations, he arrived at Beirut on 17 October 1921.[22][23] Excavation works in Jbeil were inaugurated on 20 October 1921 by the French mandate authorities, they consisted of annual campaigns of three months each.[24]

Discovery of the royal necropolis

On 16 February 1922, heavy rains triggered a landslide in the seaside cliff of Jbeil which exposed an underground man-made cavity. The next day the administrative advisor of Mount-Lebanon informed the Service of Antiquities of the landslide and announced the discovery of an ancient hypogeum containing a large unopened sarcophagus.[25][26] To keep treasure hunters at bay, the perimeter was secured by the Mudir of Jbeil Sheikh Wadih Hobeiche.[27] Virolleaud arrived at the site to clear and make an inventory of the contents of the unearthed tomb;[26] he continued to supervise the digs and opened the discovered sarcophagus on 26 February 1922.[28] A second tomb (named Tomb II) was discovered by Montet in October 1923;[29] the discovery triggered a systematic survey of the surrounding area in autumn 1923.[30] Montet headed the excavation of Ancient Byblos until 1924; during this period, he uncovered eight other tombs, bringing the total number to nine.[10] Maurice Dunand succeeded Montet in 1925 and continued his predecessor's work on the archeological tell for another forty years.[10]

Location

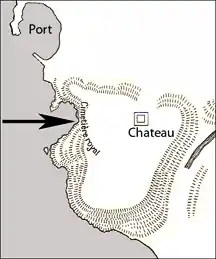

Located 42 kilometres (26 mi) north of Beirut,[31] Ancient Byblos/Gebal (modern Jbeil/Gebeil) lays south of the city's medieval center. It sits on a seaside promontory consisting of two hills separated by a dell. A 22 metres (72 ft) deep well provided the settlement with freshwater.[32][33] The highly defensible archaeological tell of Byblos is flanked by two harbors that were used for sea trade.[33] The royal necropolis of Byblos is a semicircular burial ground located on the promontory summit, on a spur overlooking both seaports of the city, within the walls of Ancient Byblos.[34][35]

Description

_LR_0115.jpg.webp)

Montet assigned numbers to the royal tombs and categorized them into two groups: the first, northern group included tombs I to IV; these were of an older construction date and were meticulously built. Tomb III and IV had been emptied from their contents by ancient looters, while the other two remained undisturbed.[36][37]

The second group of tombs is located at the southern side of the necropolis, it includes tombs V to IX. Tombs V to VIII were of inferior construction quality compared to northern ones, and were dug in clay instead of rock at a later period of time.[36][38] Only Tomb IX retained evidence of careful construction reminiscent of the earlier tombs. Earthenware fragments discovered in this tomb, bearing the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs, suggest that its construction date was closer to that the northern group. Ancient looters had broken into all the tombs of the second group.[36][39][37]

Tombs I and II

Tomb I consists of a 4 meters (13 ft) wide by 12 meters (39 ft) deep square vertical well giving access to an underground burial chamber carved partly from solid rock and partly from clay.[lower-alpha 3] The west wall, which isolated it from the exterior seaside cliff, had collapsed during the 1922 landslide.[40] The grave goods were not affected by the landslide; inside the burial chamber the excavators discovered several pottery jars floating in damp clay, and a large white limestone sarcophagus with three protruding lugs on its lid by which it could be manipulated.

The sarcophagus was placed in a north–south orientation.[41][27] A rock-cut opening is present at a height of 1 meter (3.3 ft) on Tomb I chamber's north wall, directly facing the sarcophagus. The opening leads to a 1.8 meters (5.9 ft) high and 1.2 meters (3.9 ft) to 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) wide corridor that adjoins the south side of the well of Tomb II. The same corridor is joined by a passageway emerging from the northwestern angle of Tomb I's well. Midway between Tomb I and the well of Tomb II the S-shaped corridor opens, to its north side, onto a small nondescript hole giving access to a roughly cut round cavity housing a disused archaic tomb.[41]

A coarsely built wall separated the chamber of Tomb I from its well. The well was filled to its brim with stones and mortar. The same material was used to build a platform around the well, on top of which were laid the foundations of a mastaba-like building. Little remains of the Egyptian-inspired structure because it was replaced by a Roman period bath. Unlike the well of Tomb I, the well of Tomb II was not closed off with stones and cement, but simply with earth. A thick slab of five to six rows of blocks covered the well opening and provided a foundation for a construction from which only a few masonry blocks remain.[42]

Well II is shallower than Well I; a single course wall separated it from the burial chamber. Tomb II did not contain any burial receptacles upon its discovery. A number of pottery jars and other artifacts sank in a thick layer of clay, with some of the jars damaged by falling rock shards from the chamber's ceiling. The ceiling of Tomb II's burial chamber is 3.5 meters (11 ft) high at the center of the room, it slopes down to a height of only 1 meter (3.3 ft) at its northern wall.[43] Four stones were found at the center of the chamber, they supported a wooden coffin that had disintegrated, leaving rich grave goods scattered in the clay.[29]

Montet demonstrated that Tombs I and II were not broken into before their discovery in 1922–1923 contrary to what his predecessor Virolleaud reported.[44] Virolleaud had found shards of glass lodged in the Tomb I chamber wall and assumed they dated from Roman times.[lower-alpha 4][27]

Tombs III and IV

_LR_0079.jpg.webp)

Wells III and IV are located west of Tombs I and II, adjacent to the northern wall of the Roman baths. The well opening of Tomb III measures 2.5 by 3.3 meters (8.2 ft × 10.8 ft); it was covered by a heavy layer of cement covering a masonry course sealed with ash, and vertically pierced close to its south-west angle by a square 30 centimeters (12 in) conduit reminiscent in function to that of Egyptian mastabas' serdabs. Another, similarly sized and shaped conduit traversed the deeper layer of well filling, but this one flanked the northwest angle of the well, and only ran to a depth of 2 meters (6.6 ft). The two conduits did not communicate. A niche was carved in the north wall close to the bottom of the well.[45][46]

Tomb III's burial chamber extends from the southern wall of the well, it was closed off by an uncemented single course wall. It is of fine construction with paved a floor and walls carved straight up to the ceiling.[47] Tomb III did not contain a stone sarcophagus, a number of funerary goods were found laying in a 70 centimeters (28 in) layer of clay.[48]

Tomb IV is located to the east of Tomb III; at 5.75 meters (18.9 ft) it is the shallowest of all the necropolis tombs. The well measures 3.05 by 3.95 meters (10.0 ft × 13.0 ft); its southern wall was covered by a 1 meter (3.3 ft) thick masonry wall and the burial chamber seemed undisturbed, but the excavators found that the limestone sarcophagus was opened and emptied.[49] A vertical conduit, similar to the one found in Tomb III was found in Tomb IV.[48] These conduits appear to have been a distinguishing element of the Byblos funerary cult.[36] The sarcophagus of Tomb IV lay at the center of the burial chamber facing the entryway, similar to all the other sarcophagi found in the surveyed tombs of the necropolis. The builders placed two stones at the base of the sarcophagus to support and level it on the sloping floor.[49]

Tomb V (Ahiram's Tomb)

The semicircular shape of Tomb V, known as "Ahiram's tomb", is unique within the necropolis. It was found half-filled with mud, with three tombs inside; a large plain one close to the wall, the finely-carved Ahiram sarcophagus at the center, and a smaller plain sarcophagus.[51] It was also the only tomb to have an inscription within its shaft. This inscription, dubbed the Byblos Necropolis graffito is found at a depth of 3 meters (9.8 ft) on the south wall of the shaft; it warns looters from entering the grave.[52] French epigrapher René Dussaud interpreted the graffito as "Avis, voici ta perte (est) ci-dessous" [Beware, here is your loss (is) below].[53][54][55]

The well of Ahiram's tomb is located midway between the northern tombs group (Tombs I, II, III, and IV) and the southern group (Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX). It is flanked on the west by a two course wall and column bases that were part of the tomb's superstructure. The soil on top of the well was very compacted; a conduit similar to the ones found in tombs III and IV measuring 2 meters (6.6 ft) was found in the northeast corner of the well. Molded fragments and marble plates, and numerous shards of pottery, which were markedly different from the ceramic fragments collected in the other tombs, were mixed with the earth used to fill the well. Two levels of four square slots are carved at depths of 2.2 meters (7.2 ft) and 4.35 meters (14.3 ft) respectively on both of the well's east and west walls. These four rows of slots used to hold two rows of wooden vertical beams and floors spanning the width of the well.[52] According to Montet, the builders of the tomb did not consider that the king's corpse was sufficiently protected by the shaft's surface paving slabs and by the wall built at the entrance to the chamber halfway up the well, so they laid wooden beams which acted as a third obstacle. The looters however, removed the paving and dug out the wooden structures; as they emptied the well, they could not have missed seeing the warning spell on their down to the royal grave.[55]

Below the beam slots no additional pottery shards were found, but near the bottom, against the eastward entrance to the burial chamber, several fragments of alabaster vases that had been cast out of the chamber had collected.[55][56] One of these fragments bore the name of Ramses II. The excavators found that the wall that closed off the burial chamber had partly collapsed, and the content of the room was disorderly and half-filled with muddy clay. A huge block of rock, fallen from the vault, rested atop the decorated sarcophagus of Ahiram that occupied the center of the chamber. All of the three chamber sarcophagi were looted and only contained human bones.[57]

Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX

This group of tombs is located 50 meters (160 ft) east of the necropolis cliffside and 30 meters (98 ft) south of well IV; they are built in a part of the hill with a heavy sedimentary deposit. The wells of these tombs are less well-preserved than the wells of the first group. The well of Tomb VIII was still covered with a layer of pavement, while Tombs VI and VII had lost most of their surface cover. The burial chamber of wells VI, VII, VIII, and IX are completely dug in muddy soil.[59] Grave robbers were able to burrow from one tomb to the next through the soft clay.[60]

The shaft of Tomb VI is the deepest of the all the necropolis' wells. An ashlar wall supported the shaft down to a depth of 6 meters (20 ft); beyond this depth the well continues through the muddy soil, without any masonry retaining walls.[60] Like the rest of this tomb group, Tomb VI was robbed of its content except for a few artifacts that lay in, and at the entrance of the chamber. There were no stone sarcophagi in this tomb.[59]

Tomb VII has the largest of the burial shafts, with sides measuring 5 meters (16 ft) each. The chamber of Tomb VII was dug like that of Tomb VI through hard rock and the underlying clay, and was found two-thirds filled with clay and pebbles. At the time of its excavation, the cambered lid of a stone sarcophagus rose through the layer of clay. The stone sarcophagus laid on a layer of stone pavement, and courses of stone that were in a relatively good state of conservation supported the walls of the chamber. The body of the sarcophagus of Tomb VII is roughly cut and is of simple rectangular shape. Two large lugs jut from each of the extremities of the concave lid that, like those of the sarcophagus of Tomb I, were used to manipulate the heavy cover. This tomb contained a good number of precious artifacts and jewels that appear to have been missed by looters.[61]

Tomb VIII is characterized by a lozenge shaped opening, which evens into a square at the bottom. The thin wall separating Tomb VIII from Tomb VI is perforated in its center, and Montet assumed that it was due to a quarrying accident. The well also reaches the layer of clay underlying the hard rock upper layer, and the tomb chamber was found filled with clay and gravel. The chamber had retaining walls, most of which had collapsed, and small pebbles covered the floor. A simple stone sarcophagus, a few fragments of alabaster vases, and other earthenware items were found in the tomb. No precious artifacts were recovered, except for gold foils that were mixed with the tomb's muddy soil.[62]

The well of Tomb IX cuts through 8 meters (26 ft) of rock. The wall closing off the chamber was not broken into, the looters had burrowed instead through the clay layer to access the chambers of Tomb V, VIII, and IX. The roof of Tomb IX had collapsed, and it was found filled to its brim with mud and ceiling rock shards. The chamber floor was covered by paving stones, and its walls were sturdy and in good condition. The looters almost completely emptied the contents of the tomb except for alabaster, malachite, and pottery receptacle fragments. Among the finds were terracotta artifacts bearing the names of two Gebalite kings, Abi (possibly a name contraction) and Abishemu.[63]

- Montet's sketches of the royal tombs

_LR_0117.jpg.webp) Context plan of tombs I and II

Context plan of tombs I and II_LR_0118.jpg.webp) Section view of tombs I and II

Section view of tombs I and II_LR_0119.jpg.webp) Plan and section of Tomb III

Plan and section of Tomb III_LR_0116.jpg.webp) Section views of tombs I, III and IV

Section views of tombs I, III and IV_LR_0168_(cropped).jpg.webp) Plan of Ahiram's tomb and shaft section view

Plan of Ahiram's tomb and shaft section view_LR_0120.jpg.webp) Plan and section view of tombs IV, VII, and VIII

Plan and section view of tombs IV, VII, and VIII

Finds

Sarcophagi

In total, seven stone sarcophagi were discovered in the royal necropolis of Byblos; a single sarcophagus in each of tombs I, IV, VII, VIII and three in Ahiram's tomb (Tomb V).[64][65] The other burial chambers are believed to have housed wooden caskets that have disintegrated over time.[64][65] Tomb II housed a wooden casket that has rotted away, leaving a wealth of objects laying on the burial chamber floor.[66]

The stone sarcophagi found in tombs I and IV are of fine white limestone sourced from the nearby Lebanese mountains; the walls of both sarcophagi are thick, well polished, and undecorated.[28] Moreover, the sarcophagi found in tombs I, IV, V, and VII share the same morphology which resembles the common stone sarcophagi of Egypt. One difference however, is that the lids of said Gebalite sarcophagi retain the lid lugs which allowed workmen to maneuver them.[67][41][27] These features, along with a number of tomb contents including similarly shaped alabaster containers, suggests that the entire group can be attributed to a restricted time period.[36]

The sarcophagus of Tomb I measures 1.48 by 2.82 meters (4.9 ft × 9.3 ft), and is 1.68 meters (5.5 ft) tall.[lower-alpha 5][28] The side walls of the sarcophagus are 35 centimeters (14 in) thick; the bottom of the sarcophagus body is 44 centimeters (17 in) thick.[27] The rim of the Sarcophagus I lid is beveled; it is cut from below as to enter a few centimeters into the sarcophagus body. The back of the lid is rounded and striated with lengthwise irregularly sized flutes. The central flute is the widest; it is flanked by five, decreasingly smaller flutes from each side.[68] Three lugs protrude obliquely from the lid's exterior close to its corners; the lug at the northwestern corner and an entire corner section of the lid have broken off at the foot of the sarcophagus. The sarcophagus was opened on 26 February 1922.[28][69]

The sarcophagus of Tomb IV measures 1.41 by 3 meters (4.6 ft × 9.8 ft) and is 1.49 meters (4.9 ft) tall. The body of the sarcophagus IV is slightly more sophisticated as both of its long sides are beveled at the top and bottom. The small sides have a bench-like protrusion at the base. Montet ascertains that the sarcophagus never had a stone lid; he found blackish traces on the rim of the sarcophagus body that prove that it was covered by a curved wooden lid.[70]

The sarcophagi of tombs IV, V, VII and VII were extracted during the fifth campaign, which lasted from 8 March 1926 until 26 June 1926.[71]

The Ahiram sarcophagus

The sandstone sarcophagus of Ahiram was found in Tomb V and is so called for its bas-relief carvings, and its Phoenician inscription that attributes it to King Ahiram. The inscription is one of five known Byblian royal inscriptions, it is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet. For some scholars, it represents the terminus post quem of the transmission of the alphabet to the west.[72] The sarcophagus measures 2.97 meters (9.7 ft) long by 1,115 meters (3,658 ft) wide and is 1.4 meters (4.6 ft) tall, lid included.[73]

The top of the sarcophagus body is ringed by a frieze of inverted lotus flowers. The flowers alternate between closed buds and open flowers. A motif of thick rope frames the top of the main sarcophagus bas-relief scenery, and corner pillars decorate all four sides of the sarcophagus.[74] The sarcophagus rests on four lions on each of its sides. The heads and front legs of the lions protrude outside the sarcophagus tank, while the rest of the lions' bodies appears in bas-relief on the long sides.[74]

The main scene on the body of the sarcophagus depicts the king on a throne holding a wilted lotus flower. A table full of offerings stands in front of the throne, followed by a procession of seven male figures.[75] Two scene of a funerary procession of four mourning women occupies the two small sides of the sarcophagus. Two of the women on each of the sides bare their chests, and the two others are depicted hitting their heads with their hands.[75] The scene on the back side of the sarcophagus shows a procession of men and women bearing offerings.[76]

The lid of the sarcophagus is slightly convex, like those of the neighboring sarcophagi. It has only one lug at each end, which are shaped like lion heads. The bodies of the lions are carved in bas-relief on the flat part of the lid. Two bearded effigies measuring 171 centimeters (5.61 ft) each are carved on either side of the lions; one of the figures bears a wilted lotus flower, the other a live one. Montet posited that they both represent the deceased king.[74] Lebanese archaeologist and museum curator Maurice Chehab, who later demonstrated the presence of traces of red paint on the sarcophagus, interpreted the two figures as the deceased king and his son.[77]

The Phoenician inscriptions are composed of two parts, the shortest of which is found on the sarcophagus body, in the space of the narrow band above the row of lotus flowers.[78] The longer inscription is carved on the font, long edge of the lid.[79]

Grave goods

More than 260 items were recovered from the royal necropolis of Byblos.[lower-alpha 6][81]

Egyptian royal gifts

Tomb I contained a 12 centimeters (4.7 in) obsidian vase and lid set with gold, engraved with the enthronement name of Amenemhat III in hieroglyphic characters.[82] This type of vase is known from representations of Egyptian sarcophagi of the Middle Kingdom.[83] The same grave also produced two alabaster vases [84]

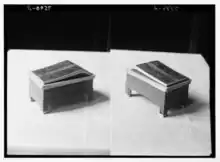

Tomb II had two royal Egyptian gifts, 45 centimeters (18 in) long obsidian box and lid set with gold; the rectangular box rests on four legs; it has at the center of the lid a perfectly preserved Egyptian hieroglyphic cartouche containing the enthronement name and epithets of Amenemhat IV.[lower-alpha 7][85] It is not clear what the contents of the box may have been; similarly shaped receptacles were often depicted on Egyptian tomb friezes and called "pr 'nti" which translate to "house of incense".[84] A stone vase carved with the name of Amenemhat IV was also found in Tomb II; the cartouche reads: "Long live The Good God, son of Ra, Amenemhat, living forever".[84]

Jewelry and precious objects

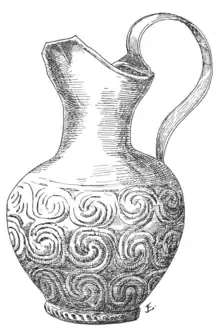

The tombs contained a wealth of royal jewelry made from gold, silver and gemstones, some of which bear a heavy Egyptian influence. Each of tombs I, II and III contained chiseled gold Egyptian-influenced pectorals. Tomb II contained an Egyptian-style, locally produced gem-encrusted gold pectoral with its chain and a shell-shaped cloisonné pendant bearing the name of King Ip-Shemu-Abi. Two grand silver hand mirrors, were recovered in tombs I and II; all of the three tombs contained bracelets and rings in gold and amethyst, silver sandals and intricately decorated and inscribed khopesh arms made from bronze and gold. The khopesh of tomb II bears the name of its owner, King Ip-Shemu-Abi and his father Abishemu. Other grave goods include a silver knife decorated with niello and gold, several bronze tridents, finely decorated teapot-shaped silver vases and various other vessels made of gold, silver, bronze, alabaster and terracotta.[86][87]

Tomb I contained a rare find of particular interest consisting of a fragment of a silver vase which French art history expert Edmond Pottier likened its spiral decorative patterns to that of the gold oenochoe from Tomb IV of Mycenae.[88] This silver vase demonstrates either Aegean artistic influence on local Gebalite art or could be proof of trade with Mycenae.[87][88]

Dating

French priest and archaeologist Father Louis-Hugues Vincent, Pierre Montet, and other early scholars believed the tombs belonged to the Kings of Byblos of the Middle and Late Bronze Age, based on the characteristics of the painted pottery shards.[89]

Tomb I, II, and III

According to Virolleaud and Montet, the lavish Tombs I, II and III date back to the Middle Bronze Age, specifically the Twelfth Dynasty of Middle Kingdom Egypt (19th century BC). Montet based his dating on grave goods and royal Egyptian gifts found in the three tombs. Tomb I housed an ointment jar etched with the cartouche of Amenemhet III, and Tomb II contained an obsidian box bearing the name of his son and successor Amenemhet IV.[90][91]

Tomb V to IX

Montet matched the style of the pottery shards that he uncovered in the shaft of Tomb V to the vases found by English Egyptologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie in the ruins of the palace of Amenophis IV at Tell-el-Amarna. Both featured large brown or black painted bands, which divide the body of the receptacles in into several parts, each of which contained vertical lines and circular motifs. Furthermore, the small vase handles are of identical shape. These similarities lead Montet to conclude that the Gebalite pottery shards were contemporary of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1550 BC –c. 1077 BC).[92][93]

The other graves of the second group (tombs VI to IX) were all robbed in antiquity, making precise dating problematic. Some signs point to a range spanning from the end of the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age for others.[94][93]

Attribution

_LR_0154.png.webp)

The names of the some of the sarcophagi occupants are known to us from archaeological finds. Tombs I belonged to King Abishemu (also romanized as "Abishemou" and "Abichemou") who received gifts from Pharaoh Amenemhat III, and Tomb II belonged to his son Ip-Shemu-Abi (also romanized as "Ypchemouabi") who received similar gifts from the son of Amenemhat IV. These gifts suggest that the reigns of Abishemu and Ip-Shemu-Abi were contemporaneous with those of late Twelfth Dynasty rulers.[29][96][97] The names of both Gebalite kings were inscribed on the khopesh staff found in Tomb II.[98] A passageway linked the chamber of Tomb I to the well of Tomb II. Montet posited that that Ip-Shemu-Abi had this tunnel dug to remain in constant communication with his father.[99]

Montet proposed that Tomb IV was made for a vassal king of Egyptian origin, whom he believes was appointed by Egypt, thus interrupting the Gebalite dynastic suite. This theory was put forward based on Montet's discovery of an Egyptian scarab inscribed with the Egyptian name Medjed-Tebit-Atef.[96][100]

The sarcophagus of Tomb V belongs to Ahiram;[67] it stands apart from the other sarcophagi for its rich decoration and reliefs. Ahiram's sarcophagus was found in the chamber of Tomb V with two other plain sarcophagi. The lid of the sarcophagus features the effigies of the deceased, and that of his successor. A funerary inscription written in Phoenician identify the names of the deceased king, and his son and successor Pilsibaal.[lower-alpha 8][77][103]

Earthenware fragements discovered in Tomb IX bore the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs.[37] This led scholars to attribute the sarcophagus to Abishemu, the second of that name, who could be the grandson of the elder. This assumption is based on the Phoenician custom of naming a prince after his grandfather.[104]

Function

Montet likened the Byblos tombs to mastabas and explained that in ancient Egyptian funerary texts, the deceased is believed to take the form of a bird and fly from the burial vault and the funerary well to the ground-level chapel where priests officiate.[105] He likened the tunnel connecting Tombs I and II to the tomb of Aba the son of Zau, a high official contemporaneous of Pharaoh Pepi II, who was buried in Deir el-Gabrawi in the same tomb as his father. Aba left an inscription detailing how he chose to share the tomb of his father to "be with him in the same place".[lower-alpha 9][105]

See also

Notes, references, and bibliography

Notes

- The demonyms Gebalite or Giblite are used in ancient sources to designate the general population of Gebal, the Phoenician name, and the origin of the modern name of the city (Jbeil).[12][13] Byblos is a much later Greek exonym, possibly a corruption of Gebal.[8] In the context of this article, the demonym Gebalite was used since the site in question dates back to Phoenician times, and predates the exonym of Byblos.

- Now Byblus, the royal residence of Cinyras, is sacred to Adonis; but Pompey freed it from tyranny by beheading its tyrant with an axe; and it is situated on a height only a slight distance from the sea.[18]

- The rock bank found in this part of the peninsula, 4 meters (13 ft) or 5 meters (16 ft) from the current ground, is only 6 meters thick. The workers who dug the well, therefore, crossed it from the side and, not considering the depth sufficient, continued to dig in the clay.[40]

- "II semble bien que personne n'ait tenté de soulever le couvercle du sarcophage. Cependant quelqu'un est entré dans la grotte, à l'époque romaine sans doute, puis qu'on a trouvé mêlés aux pierres du mur de soutènement des fragments de verre qui datent sûrement de ce temps-là." [It seems that no one has tried to lift the lid of the sarcophagus. However, someone entered the cave, probably in Roman times, and glass fragments were found mixed with the stones of the retaining wall, which surely date from that time.] [27]

- 2.32 meters (7.6 ft) including the lid [27]

- Objects recovered from the royal tombs are numbered from 610 to 872 in Montet's Atlas.[80]

- "Vive le dieu bon, maître des Deux Terres, roi de la Haute et Basse Égypte, Ma'a-kherou-rê, aimé de Tourn, seigneur d'Héliopolis (On), à qui est donnée la vie éternelle comme Râ." ["Long Live The Good God, Master of both lands, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ma'a-kherou-re, beloved of Tourn, Lord of Heliopolis (On), to whom eternal life is given as Ra."] [84]

- The reconstruction of the name of Ahiram's son from the sarcophagus inscription was a point of contention due to the presence of a lacuna at the beginning of the prince's name. Since the Ahiram sarcophagus inscription was originally published in 1924, the name Ittobaal had prevailed. New epigraphic analyses reveal that this long-held interpretation is impossible, and a new reconstruction was presented using modern palaeographic and calligraphic methods. These have demonstrated that Ahiram's son's name must have been Pulsibaal or Pilsibaal.[101][102]

- "I therefore made sure to be buried in the same tomb, with this Zau, in order to be with him in the same place, not that I did not have the means to make a second tomb, but I did this in order to see this Zau every day, in order to be with him in the same place."[105]

References

- Cooper 2020, p. 298.

- Wilkinson 2011, p. 66.

- Moran 1992, p. 143.

- Head et al. 1911, p. 763.

- Huss 1985, p. 561.

- Lehmann 2008, p. 120, 121, 154, 163–164.

- Salameh 2017, p. 353.

- Harper 2000.

- DeVries 2006, p. 135.

- DeVries 1990, p. 124.

- Awada Jalu 1995, p. 37.

- Head et al. 1911, p. 791.

- Barry 2016, headword: Gebal.

- Fischer 2003, p. 90.

- Segert 1997, p. 58.

- Moran 1992, p. 197.

- Charaf 2014, p. 442.

- Strabo, §16.2.18.

- Montet 1928, p. 2–3.

- Renan 1864, p. 173.

- Dussaud 1956, p. 9.

- D. 1921, pp. 333–334.

- Montet 1921, pp. 158–168.

- Vincent 1925, p. 163.

- Virolleaud 1922, p. 1.

- Dussaud 1956, p. 10.

- Virolleaud 1922, p. 275.

- Montet 1928, pp. 153–154.

- Montet 1928, pp. 145–147.

- Vincent 1925, p. 178.

- Sparks 2017, p. 249.

- Moore 1978, p. 330.

- Lendering 2020.

- Montet 1928, p. 22–23, 143.

- Nigro 2020, p. 67.

- Porada 1973, p. 356.

- Montet 1928, p. 212.

- Montet 1928, p. 214.

- Montet 1928, p. 155.

- Montet 1928, p. 143.

- Montet 1928, p. 144.

- Montet 1928, pp. 144–145.

- Montet 1928, pp. 145–146.

- Montet 1928, p. 146.

- Montet 1928, p. 148–150.

- Montet 1929, p. Pl. LXXVI (illustration).

- Montet 1928, p. 150.

- Montet 1928, p. 151.

- Montet 1928, pp. 152–153.

- Vincent 1925, PLANCHE VIII.

- Porada 1973, p. 356–357.

- Montet 1928, pp. 215–216.

- Dussaud 1924, p. 143.

- Vincent 1925, p. 189.

- Montet 1928, p. 217.

- Porada 1973, p. 357.

- Montet 1928, p. 217, 225.

- Dunand 1937, XXVIII.

- Montet 1928, p. 205–206.

- Montet 1928, p. 205.

- Montet 1928, p. 207–210.

- Montet 1928, p. 210.

- Montet 1928, p. 210–213.

- Montet 1929, p. 118–120.

- Montet 1928, p. 144, 146, 151–153 ,205–220, 229.

- Montet 1928, p. 146–147.

- Porada 1973, p. 355.

- Virolleaud 1922, p. 276.

- Virolleaud 1922, pp. 275–276.

- Montet 1928, p. 154.

- Dunand 1939, p. 2.

- Cook 1994, p. 1.

- Babey.

- Montet 1928, p. 229.

- Montet 1928, p. 230.

- Montet 1928, p. 231.

- Porada 1973, p. 359.

- Montet 1928, p. 236.

- Montet 1928, p. 237.

- Montet 1929, pp. 4–6.

- Montet 1928, p. 202.

- Montet 1928, pp. 155–156.

- Jéquier 1921, p. 142.

- Montet 1928, p. 159.

- Montet 1928, pp. 157–159.

- Montet 1928, pp. 155–204.

- Dussaud 1930, pp. 176–178.

- Pottier 1922, pp. 298–299.

- Montet 1928, pp. 129, 219.

- Virolleaud 1922, pp. 273–290.

- Montet 1928, pp. 16–17, 25, 219.

- Montet 1928, p. 220.

- Kilani 2019, p. 97.

- Montet 1928, pp. 213–214.

- Montet 1929, PLANCHE CXI.

- Dussaud 1930, p. 176.

- Montet 1927, p. 86.

- Montet 1928, p. 174.

- Montet 1928, p. 147.

- Montet 1928, p. 203.

- Lehmann 2005, p. 38.

- Lehmann 2015, p. 178.

- Lehmann 2008, p. 164.

- Helck 1971, p. 67.

- Montet 1928, pp. 147–148.

Bibliography

- Awada Jalu, Sawsan (1995). "The stones of Byblos". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- Babey, Maurice. "Ahiram Sarcophagus / Byblos / 13th Century". akg-images. Archived from the original on 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- Barry, John D. (2016). The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

- Charaf, Hanan (2014). "The northern Levant (Lebanon) during the Middle Bronze Age". In Steiner, Margreet L.; Killebrew, Ann E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000-332 BCE. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978019166255-3.

- Cook, Edward M. (1994). "On the Linguistic Dating of the Phoenician Ahiram Inscription (KAI 1)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 53 (1): 33–36. doi:10.1086/373654. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 545356. S2CID 162039939.

- Cooper, Julien (2020). Toponymy on the Periphery: Placenames of the Eastern Desert, Red Sea, and South Sinai in Egyptian Documents from the Early Dynastic until the End of the New Kingdom. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9789004422216.

- D., R. (1921). "Mission Pierre Montet à Byblos" [Pierre Montet's mission in Byblos]. Syria (in French). 2 (4): 333–334. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4389726 – via JSTOR.

- Dever, William Gwinn (1976). "The Beginning of the Middle Bronze Age in Syria-Palestine". In Cross, Frank Moore; Lemke, Werner E.; Wright, George Ernest; Miller, Patrick D., Jr. (eds.). Magnalia Dei : the mighty acts of God : essays on the Bible and archaeology in memory of G. Ernest Wright. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385052573.

- DeVries, LaMoine F. (1990). Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey; McKnight, Edgar V. (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- DeVries, LaMoine F. (2006). Cities of the Biblical World: An Introduction to the Archaeology, Geography, and History of Biblical Sites. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781556351204.

- Dunand, Maurice (1939). Fouilles de Byblos: Tome 1er, 1926-1932 [The Byblos excavations, Tome 1, 1926–1932]. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique (in French). Vol. 24. Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner.

- Dunand, Maurice (1937). Fouilles de Byblos, Tome 1er, 1926–1932 (Atlas) [The Byblos excavations, Tome 1, 1926–1932 (Atlas)]. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique (in French). Vol. 24. Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner – via gallica.bnf.fr.

- Dussaud, René (1924). "Les inscriptions phéniciennes du tombeau d'Ahiram, roi de Byblos" [Phoenician inscriptions from the Tomb of Ahiram, King of Byblos]. Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire (in French). 5 (2): 135–157. doi:10.3406/syria.1924.3038 – via Persée.

- Dussaud, René (1930). "Les quatre campagnes de fouilles de M. Pierre Montet a Byblos" [The four excavation campaigns of Mr. Pierre Montet at Byblos]. Syria (in French). 11 (2): 164–187. doi:10.3406/syria.1930.3470. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4237002 – via JSTOR.

- Dussaud, René (1956). "L'oeuvre scientifique syrienne de M.Charles Virolleaud". Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire. 33 (1): 8–12. doi:10.3406/syria.1956.5186.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (2003). History of Writing. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861891679.

- Harper, Douglas (2000). "Etymology of Byblos". Online Etymology Dictionary. Tupalo, MS: Douglas Harper. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2022-03-15.

- Head, Barclay Vincent; Hill, Sir George Francis; MacDonald, George; Wroth, Warwick William (1911). Historia Numorum: A Manual of Greek Numismatics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780722221877.

- Helck, Wolfgang (1971). Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v.Chr.: 2., verbesserte Auflage [Relations between Egypt and the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC]. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen (in German). Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447012980.

- Huss, Werner (1985). Geschichte der Karthager (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. p. 561. ISBN 9783406306549.

- Jéquier, Gustave (1921). "Les frises d'objets des sarcophages du Moyen Empire" [Friezes of objects of sarcophagi of the Middle Kingdom]. Mémoires de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire (in French). Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. 47 – via archive.org.

- Kilani, Marwan (2019-10-07). Byblos in the Late Bronze Age: Interactions between the Levantine and Egyptian Worlds. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-41660-4.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2005). Die Inschrift(en) des Ahirom-Sarkophags und die Schachtinschrift des Grabes V in Jbeil (Byblos) [The inscription(s) of the Ahirom sarcophagus and the shaft inscription of Tomb V in Jbeil (Byblos)] (in German). Mainz am Rhein von Zabern. ISBN 9783805335089. OCLC 76773474.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2008). "Calligraphy and Craftsmanship in the Ahirom inscription. Considerations on skilled linear flat writing in early first millennium Byblos". MAARAV. Santa Monica (Calif.): Western Academic Press. 15 (2): 119–164.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (February 2015). Wer war Aḥīrōms Sohn (KAI 1:1)? Eine kalligraphisch-prosopographische Annäherung an eine epigraphisch offene Frage [Who was Aḥīrōm's son (KAI 1:1)? A calligraphic-prosopographic approach to an epigraphically open question]. Fünftes Treffen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Semitistik in der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, University of Basel. Alter Orient und Altes Testament. Vol. 425. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 163–180.

- Lendering, Jona (2020). "Byblos". Livius. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- Montet, Pierre (1921). "Lettre à M. Clermont-Ganneau" [Letter to Mr. Clermont-Ganneau]. Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 65 (2): 158–168. doi:10.3406/crai.1921.74450.

- Montet, Pierre (1927). "Un Egyptien, roi de Byblos, sous la XIIe dynastíe Étude sur deux scarabées de la collection de Clercq" [An Egyptian king of Byblos under the Twelfth Dynasty, study on two scarabs from the Clercq collection]. Syria (in French). 8 (2): 85–92. doi:10.3406/syria.1927.3277. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4195343 – via JSTOR.

- Montet, Pierre (1928). Byblos et l'Egypte: Quatre Campagnes de Fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 (Texte) [Byblos and Egypt: four excavation campaigns in Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 (Text)]. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique (in French). Vol. 11. Paris: Geuthner – via archive.org.

- Montet, Pierre (1929). Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre Campagnes de Fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 (Atlas) [Byblos and Egypt: four excavation campaigns in Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 (Atlas)]. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique (in French). Vol. 11. Paris: Geuthner – via archive.org.

- Moore, Andrew Michael Tangye (1978). The neolithic of the Levant (Thesis). Ann Arbor: University of Oxford.

- Moran, William L. (1992). The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4251-1.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (2020). "Byblos, an ancient capital of the Levant". Revue Phénicienne. 10.

- Porada, Edith (1973). "Notes on the Sarcophagus of Ahiram". Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society. 5 (1): 2166.

- Pottier, Edmond (1922). "Observations sur quelques objets trouvés dans le sarcophage de Byblos. Lettre à M. René Dussaud, Directeur de la revue Syria". Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire. 3 (4): 298–306. doi:10.3406/syria.1922.8854.

- Renan, Ernest (1864). Mission de Phénicie Dirigée par M. Ernest Renan [Mission to Phénicia, directted by Mr. Ernest Renan] (in French). Paris: Imprimerie impériale.

- Salameh, Franck (2017). The other Middle East: An anthology of modern Levantine literature. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300204445.

- Segert, Stanislav (1997). Kaye, Alan S.; Daniels, Peter T (eds.). Phonologies of Asia and Africa - including the Caucasus. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-019-4.

- Sparks, Rachael Thyrza (2017-07-05). Stone Vessels in the Levant. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-54778-9.

- Strabo. Geographica. Vol. 2. p. 755. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- Vincent, L. H. (1925). "Les fouilles de Byblos" [The excavations of Byblos]. Revue Biblique (1892-1940) (in French). 34 (2): 161–193. ISSN 1240-3032. JSTOR 44102762.

- Virolleaud, Charles (1922). "Découverte a Byblos d'un hypogée de la douziéme dynastie égyptienne" [Discovery in Byblos of a Hypogeum of the Egyptian Twelfth Dynasty]. Syria (in French). 3 (4): 273–290. doi:10.3406/syria.1922.8851. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4195157 – via JSTOR.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2011). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York, NY: A&C Black. ISBN 9780553384901.

_LR_0170_(cropped).jpg.webp)