Reedy Creek Improvement District

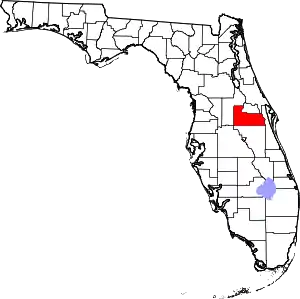

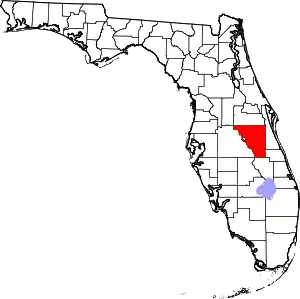

The Reedy Creek Improvement District (RCID) is the governing jurisdiction and special taxing district for the land of Walt Disney World Resort. It includes 39.06 sq mi (101.2 km2) within the outer limits of Orange and Osceola counties in Florida. It acts with the same authority and responsibility as a county government.[1] It includes the cities of Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, and unincorporated RCID land.

Reedy Creek Improvement District | |

|---|---|

| |

|

Logo | |

| Etymology: Reedy Creek, a natural waterway that flows through | |

Map showing RCID cities of Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Orange, Osceola |

| Established | May 12, 1967 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 39.06 sq mi (101.2 km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Area code(s) | 407, 689 |

| Website | www |

The district was created in 1967 after the Florida Government passed the Reedy Creek Improvement Act. The law was pushed for by Walt Disney and his namesake media company both before and after Disney's death in 1966, during the planning stages of Walt Disney World.

Because of incidents that occurred over many years, the district has been criticized for acting in the interests of Disney instead of the public. The district has the authority of a governmental body, but is not subjected to the constraints of a governmental body.[2] A major selling point in lobbying the Florida Government to establish the district was Walt Disney's proposal of the "Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow" (EPCOT), a real planned community intended to serve as a testbed for new city-living innovations. The company however eventually decided to abandon Walt Disney's concepts for the experimental city, primarily only building a resort similar to its other parks.

In April 2022, the Florida Legislature passed a law abolishing the RCID along with special districts formed prior to November 5, 1968.[3] Some members of the Florida Legislature as well as political commentators claimed the action was retaliation stemming from Disney's opposition to the controversial Parental Rights in Education Act, known as the "Don’t Say Gay” bill by its critics.[4][5] The law takes effect in June 2023, at which time the RCID would be dissolved; however, it is unclear what will happen to the $1 billion in bond liabilities held by the RCID.[6][7][8]

History

Initial steps

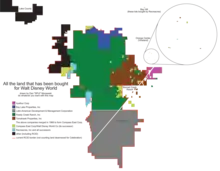

After the success of Disneyland in California, Walt Disney began planning a second park on the East Coast. He disliked the businesses that had sprung up around Disneyland, and wanted control of a much larger area of land for the new project.[9] He flew over the Orlando-area site, and many other potential sites, in November 1963.[10] Seeing the well-developed network of roads, including the planned Interstate 4 and Florida's Turnpike, with McCoy Air Force Base (later Orlando International Airport) to the east, he selected a centrally located site near Bay Lake. He used multiple shell companies to buy up land, at very low prices, that eventually became the district. These company names are listed on the upper story windows of what is now the Main Street USA section of Walt Disney World, including Compass East Corporation; Latin-American Development and Management Corporation; Ayefour Corporation (named for nearby I-4); Tomahawk Properties, Incorporated; Reedy Creek Ranch, Incorporated; and Bay Lake Properties, Incorporated.[10]

On March 11, 1966, these landowners, all fully owned subsidiaries of what is now The Walt Disney Company, petitioned the Circuit Court of the Ninth Judicial Circuit, which served Orange County, Florida, for the creation of the Reedy Creek Drainage District under Chapter 298 of the Florida Statutes. After a period during which some minor landowners within the boundaries opted out, the Drainage District was incorporated on May 13, 1966, as a public corporation. Among the powers of a Drainage District were the power to condemn and acquire property outside its boundaries "for the public use". It used this power at least once to obtain land for Canal C-1 (Bonnet Creek) through land that is now being developed as the Bonnet Creek Resort, a non-Disney resort.[11]

Improvement district and cities

Walt Disney knew that his plans for the land would be easier to carry out with more independence. Among his ideas for his Florida project was his proposed EPCOT, the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, which was to be a futuristic planned city (and which was also known as Progress City).[12] He envisioned a real working city with both commercial and residential areas, but one that also continued to showcase and test new ideas and concepts for urban living.[11] Therefore, the Disney company petitioned the Florida State Legislature for the creation of the Reedy Creek Improvement District, which would have almost total autonomy within its borders. Residents of Orange and Osceola counties did not need to pay any taxes unless they were residents of the district. Services like land use regulation and planning, building codes, surface water control, drainage, waste treatment, utilities, roads, bridges, fire protection, emergency medical services, and environmental services were overseen by the district.[11] The only areas where the district had to submit to the county and state would be property taxes and elevator inspections.[9] The planned EPCOT city was also emphasized in this lobbying effort.

On May 12, 1967, Governor Claude R. Kirk Jr. signed the Reedy Creek Improvement Act, adding the following Florida statutes to implement Disney's plans:[13]

- Chapter 67-764 created the Reedy Creek Improvement District;

- Chapter 67-1104 established the City of Bay Lake; and

- Chapter 67-1965 established the City of Reedy Creek (later renamed as the City of Lake Buena Vista around 1970.)

According to a press conference held in Winter Park, Florida on February 2, 1967 by Disney Vice President Donn Tatum, the Improvement District and Cities were created to serve "the needs of those residing there", because the company needed its own government to "clarify the District's authority to [provide services] within the District's limits", and because of the public nature of the planned development. The original city boundaries did not cover the whole Improvement District; they may have been intended as the areas where communities would be built for residential use.[9][11]

Further development

In 1993, the land that eventually became the Disney-controlled town of Celebration, Florida—which was built with many of Walt Disney's original ideas that had since evolved into a form of New Urbanism—was deannexed from Bay Lake and the District.[14] This was done to keep its residents from having power over Disney by providing for separate administration of the areas. Celebration lies on unincorporated land within Osceola County, with a thin strip of still-incorporated land separating it from the rest of the county. This strip of land contains canals and other land used by the District.[11]

The Reedy Creek Improvement Act was held by the Supreme Court of Florida not to violate any provision of the Constitution of Florida.[15] As the law, in part, declares that the District is exempt from all state land use regulation laws "now or hereafter enacted," the Attorney General of Florida has issued an opinion stating that this includes state requirements for developments of regional impact (DRIs).[16]

After Walt Disney died in 1966, the Disney company board decided that it did not want to be in the business of running a city, and abandoned many of his ideas for Progress City. The planned residential areas were never built.[11] Most notably, Richard Foglesong argues in his book, Married to the Mouse: Walt Disney World and Orlando, that Disney has abused its powers by remaining in complete control of the District.[9]

In January 1990, the RCID was granted a $57-million allocation of tax-free state bonds over an agency with plans for a low-income housing development and all additional government applicants in a six-county region, as the state distributed the bond proceeds on a first-come order. Disney was criticized for the move, with a Republican gubernatorial candidate filing a lawsuit to stop the RCID from using the funds. Also, one state legislator moved to limit the RCID's ability to apply for the program.[17]

Abolition

On March 30, 2022, State Representative Spencer Roach tweeted that Florida legislators had met twice within the past week to discuss the possibility of repealing the Reedy Creek Improvement Act and stripping Disney of its "special privileges" in the state. Roach and Florida governor Ron DeSantis later criticized Disney for the "special perks" the company enjoyed through use of the RCID. Roach said there had been previous attempts to eliminate the district.[18] A bill analysis and fiscal impact statement for the bill was created on April 19, 2022 by Senator Jennifer Bradley.[19]

On April 20, 2022, the Florida Senate passed Senate Bill 4C (SB 4C) with a 26–13 vote that would abolish the special taxing district. If it became law, the bill would dissolve any independent special district in Florida established prior to November 5, 1968, including the RCID; the dissolution would take effect June 1, 2023.[20][21] On April 21, 2022, the bill was passed by the Florida House by a 70–38 vote.[22] DeSantis signed the bill into law the following day.[23] Some members of the Florida Legislature as well as political commentators said the bill was likely retaliation for Disney announcing its opposition to the Parental Rights in Education Act, dubbed by critics as the "Don't Say Gay bill". Representative Dotie Joseph dubbed SB 4C "un-American" adding that it was "[p]unishing a company for daring to speak against a governor's radical-right political agenda".[24][4][5]

Potential repercussions

The bill was passed after two days of discussions and without a fiscal impact analysis. This led to debates about the bill's effects on taxes and bond debt.[25] Randy Fine, the Republican House sponsor of the bill, claimed without providing evidence that the tax revenue would instead go to local governments and that taxpayers would save money.[25]

Disney already pays property taxes to Orange and Osceola counties. The bill would not increase these counties' revenues but would force both counties to increase services within the former jurisdiction of the RCID. A tax collector for Orange County claimed the RCID's abolition would increase costs for taxpayers. Florida Senate Minority Leader Gary Farmer also highlighted concerns that the dissolution would transfer over $1 billion in bond liabilities to all Florida taxpayers.[26]

Potential legal challenges

Analysts expected legal challenges to the dissolution. One argument was that because the law targeted Disney in retaliation for a political position, it violated the company's free speech rights under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[27]

Another argument is that the dissolution violates the contract the state of Florida made with bondholders not to alter or limit the powers of the district until all bonds were paid off, making the dissolution unconstitutional under the Contract Clause.[6][7][8] Under Florida law, when a special district government, like the Reedy Creek Improvement District, is dissolved, the dissolution transfers "title to all property owned by the preexisting special district government to the local general-purpose government, which shall also assume all indebtedness of the preexisting special district."[28] In 1866, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that "once a local government issues a bond based on an authorized taxing power, the state is contract-bound and cannot eliminate the taxing power supporting the bond".[6]

Naming

Reedy Creek is a natural waterway whose flow, drainage, and destination have been altered over the years by human development. It begins west of the Bay Lake city limits and the Magic Kingdom, and then meanders south through Disney property, passing between Disney's Animal Kingdom and Blizzard Beach. It crosses Interstate 4 and exits Disney property west of Celebration and runs mostly through undeveloped territory east of Haines City. It empties into Lake Russell, and continues flowing southward into Cypress Lake, which is connected to the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes.[29]

Governance

A five-member Board of Supervisors governs the District, elected by the landowners of the District. These members, senior employees of The Walt Disney Company, each own undeveloped five-acre (2.0 ha) lots of land within the District, the only land in the District not technically controlled by Disney or used for public road purposes. The only residents of the District, also Disney employees or their immediate family members, live in two small communities, one in each city. In the 2000 U.S. Census, Bay Lake had 23 residents, all in the community on the north shore of Bay Lake, and Lake Buena Vista had 16 residents, all in the community about a mile north of Disney Springs. These residents elect the officials of the cities, but since they do not actually own any land, they do not have any power in electing the District Board of Supervisors.

The District headquarters are in a building in Lake Buena Vista, east of Disney Springs.[30] The District runs the following services, primarily serving Disney:

- Law enforcement – Officers from Orange County, Osceola County and the Florida Highway Patrol are contracted to police the district. In addition, the Walt Disney Company employs about 800 security staff in their Disney Safety and Security division. While Disney security maintains a fleet of private security Chevrolet Equinoxes equipped with flashing amber and green lights, flares, traffic cones, and chalk commonly used by police officers, arrests and citations are issued by the Florida Highway Patrol along with the Orange County and Osceola County sheriffs deputies.Disney security personnel are involved with traffic control and may only issue personnel violation notices to Disney and RCID employees, not the general public.[9] Security vans previously had red lightbars, but after public scrutiny following the death of Robb Sipkema,[2] were changed to amber to fall in line with Florida State Statutes.[31]

- Environmental protection: Many pieces of land have been donated to the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation and the South Florida Water Management District as conservation easements, and the District collects data and ensures that large portions remain in their natural wetland state.[30]

- Building codes and land-use planning – The "EPCOT Building Codes" were implemented to provide the sort of flexibility that the innovative community of EPCOT would require. The provisions contained therein, although rumored to be exceptionally stringent, have in fact never been far and above those of the Standard Building Code or the Florida Building Code (FBC) that is currently in force in the rest of Florida. In fact, since the inception of the International Building Code (IBC) in 2000, the EPCOT Building Code defers much of its design parameters to the IBC-based FBC, and many of the reference standards contained therein. Particularly with regard to wind design, today's standards are better than the ones that previously existed, and today's RCID buildings are built to withstand 110 mph (180 km/h) winds. Hurricane Charley (2004) reached maximum sustained winds estimated 85 mph (137 km/h) at the nearby Orlando International Airport but winds were lower on RCID property. Although the codes are ostensibly updated on a three-year cycle, the most recent and currently used version of the EPCOT Building Codes is the 2018 version.[32][30]

- Utilities – wastewater treatment and collection, water reclamation, electric generation and distribution, solid waste disposal, potable water, natural gas distribution, and hot and chilled water distribution are managed through Reedy Creek Energy Services, which has been merged with the Walt Disney World Company[30]

- Roads – Many of the main roads in the District are public roads maintained by the District, while minor roads and roads dead-ending at attractions are private roads maintained by Disney; in addition, state-maintained Interstate 4 and U.S. Highway 192 pass through the District, as does part of the right-of-way of County Road 535 (formerly State Road 535).[30]

Disney provides transportation for guests and employees in the form of buses, ferries, and monorails, under the name Disney Transport. In addition, several Lynx public bus routes enter the District, with half-hour service between the Transportation and Ticket Center (and backstage areas at the Magic Kingdom) and Downtown Orlando and Kissimmee, and once-a-day service to more points, intended mainly for cleaning staff. Half-hourly service is provided, via Lynx, to Orlando International Airport (MCO).[30]

Fire department

The Reedy Creek Fire Department (RCFD) was created in 1968 to provide fire suppression for RCID. Today, RCFD provides fire suppression, emergency medical services, 911 communications, fire inspections, technical rescue services, and hazardous materials mitigation. EMS makes up approximately 85 percent of the call volume, with RCFD providing both Advanced Life Support and Basic Life Support.[33]

RCFD currently staffs four fire stations located throughout the district with 138 personnel across three shifts. They also maintain a staff of 86 administrative and support personnel including EMS team members (primarily located in each of the four Walt Disney World theme parks), 911 communicators, and fire inspectors among others.[34] There are four engines, two-tower trucks, one squad unit, eight rescue ambulances and several special units.

References

- "About". Reedy Creek Improvement District. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- Fritz, Mark (November 3, 1996). "Disney's Wild World of Lawyers: The Scrappiest Place on Earth?". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- "SB 4-C". Florida Senate. April 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- Woodward, Alex (April 20, 2022). "How Florida residents could end up paying for the GOP's war with Disney over 'Don't Say Gay'". The Independent.

- "Florida Senate Votes To End Walt Disney World's Reedy Creek Improvement District". CBS Miami. April 21, 2022.

- "Florida's Contractual Obligations to Bond Holders Block Repeal of Disney's Special Taxing District, Says Reedy Creek in New Statement". Law & Crime. April 26, 2022. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022.

- "The Contractual Impossibility of Unwinding Disney's Reedy Creek". Bloomberg Tax. April 26, 2022.

- "Disney's special district tells investors state can't dissolve it without paying debt". Miami Herald. April 27, 2022. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022.

- Fogleson, Richard E. (2003). Married to the Mouse. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09828-0.

- Mannheim, Steve (2002). Walt Disney and the Quest for Community. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 68–70. ISBN 0-7546-1974-5.

- "History". Reedy Creek Improvement District. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- Fickley-Baker, Jennifer (August 11, 2011). "A Closer Look at the Progress City Model at Magic Kingdom Park". Disney Parks Blog. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- "Laws of Florida, Chapter 67-764, House Bill No. 486" (PDF). May 12, 1967. pp. 266–368. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- "Existing Land Use" (PDF). Reedy Creek Improvement District Comprehensive Plan 2020. October 7, 2010. p. 2B-11. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- State v. Reedy Creek Improvement District, 216 So.2d. 202 (Fla. 1968).

- "Advisory Legal Opinion – AGO 77-44: Developments of Regional Impact – Applicability of Ch. 380 to Disney World". Florida Office of the Attorney General. May 16, 1977.

- Richter, Paul (July 8, 1990). "Disney's Tough Tactics". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- "Magic no more? DeSantis questions Disney's special operating city in Florida". NBC News. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Bradley, Jennifer (April 19, 2022). "The Florida Senate Bill Analysis and Fiscal Impact Statement; SB 4-C" (PDF). Florida Senate. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- "Senate Bill 4C (2022C)". Florida Senate. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- "Florida Senate passes bill to dissolve Disney's 'independent special district' in special session". April 20, 2022.

- Whitten, Sarah (April 21, 2022). "Florida Republicans vote to dissolve Disney's special district, eliminating privileges and setting up a legal battle". CNBC. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "DeSantis signs bill eliminating Walt Disney World's Reedy Creek district; Fitch warns of bond downgrade". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Barnes, Brooks (April 21, 2022). "Disney to Lose Special Tax Status in Florida Amid 'Don't Say Gay' Clash". New York Times.

- Swisher, Skyler; Gillespie, Ryan (April 22, 2022). "Disney World's Reedy Creek: What happens after the special district is abolished?". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Frias, Lauren (April 21, 2022). "Florida Gov. DeSantis may repeal Disney's special tax status. But tax officials and legislators say the move could leave local taxpayers to cover more than $1 billion in bond debt". Business Insider. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Ron DeSantis May Be Set Up for Courtroom Loss Against Disney

- Florida Statutes section 189.076(2)

- "Upper Reedy Creek: Intercession City, Reedy Creek and Lake Russell". South Florida Water Management District. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- "Reedy Creek Improvement District". Disney Park History. June 26, 2008. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- Bell, Maya (May 4, 1997). "Mickey's Identity Crisis – Courts Deciding If Disney World Is A Government, Business Or Both". Orlando Sentinel. p. G1. Archived from the original on March 10, 2019.

- "Reedy Creek Improvement District – Lake Buena Vista, Florida". Rcid.org. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- "Reedy Creek Fire Rescue". reedycreek.unionactive.com. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- "Reedy Creek Professional Firefighters | Operations Suppression". reedycreek.unionactive.com. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

Further reading

- Richard Foglesong (2001), Married to the Mouse: Walt Disney World and Orlando, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08707-1, ISBN 0-300-09828-6

- Sam Gennawey (2011), Walt Disney and the Promise of Progress City, Theme Park Press, ISBN 978-0-615-54024-5