Westland petrel

The Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica), (Māori: tāiko), also known as the Westland black petrel, is a moderately large seabird in the petrel family Procellariidae, that is endemic to New Zealand. Described by Robert Falla in 1946, it is a stocky bird weighing approximately 1,100 grams (39 oz). It is a dark blackish-brown colour with black legs and feet. It has a pale yellow bill with a dark tip.

| Westland petrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Procellaria |

| Species: | P. westlandica |

| Binomial name | |

| Procellaria westlandica Falla, 1946 | |

| |

| Westland petrel range | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

This species spends the majority of its life at sea but returns to land to breed. When at sea, it ranges across areas of the Pacific and Tasman seas around the subtropical convergence and migrates east to South American waters during the non-breeding season. They are nocturnal and feed on fish, squid and crustaceans. This species is also known to be an opportunistic feeder, scavenging fish waste discarded by hoki fishers.

The only known breeding colonies of the Westland petrel are in forest-covered coastal foothills on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand, between Barrytown and Punakaiki. The birds nest in burrows excavated into hillsides and slopes, and exhibit natal philopatry, that is they return to their natal colony to breed. The loss of a breeding colony can therefore have severe consequences for the population. The total area of all breeding colonies combined is only about 0.16 km2 (0.062 sq mi). In 2014, the breeding colony areas suffered extensive damage from landslips and tree fall during a severe storm. Other significant potential threats to the breeding colonies are predation by feral pigs and vagrant dogs from nearby settlements.

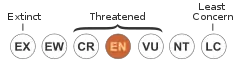

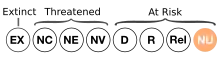

As of 2021, the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified this species as endangered, and the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified this species as "At Risk: Naturally Uncommon" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.

Taxonomy

.jpg.webp)

The Westland petrel was first described by Robert Falla in 1946 under the name Procellana parkinsoni westlandica.[4] The Westland petrel was identified in 1945 after the students of Barrytown School wrote to Falla, as he was then the Director of the Canterbury Museum.[4] They had heard in a radio broadcast about the sooty shearwater/muttonbird, but noticed that the behaviour of the 'mutton birds' in their area was quite different.[4] They also sent Falla a dead bird, and within a few weeks he visited the West Coast. Initially he considered that the West Coast birds were a subspecies of the black petrel Procellaria parkinsoni, but it was soon classified as a separate species.[5][3] The male holotype specimen, collected at Barrytown on the 29 April 1946, is held at the Canterbury Museum.[4]

The Māori name is tāiko, which also refers to the black petrel, Procellaria parkinsoni.[6]

Description

The adult Westland petrel is a stocky looking bird, weighing around 1,100 grams (39 oz). It is entirely dark blackish-brown, with black legs and feet. Some individuals may have a few white feathers. The bill is pale yellow with a dark tip.[7] Falla measured the female and male birds for his original description and pointed out that the male of the species measured slightly larger than the female.[4] However the female specimen weighted slightly more than the male.[4]

Falla described the eggs of this species as follows:

These were white, smooth, without gloss and generally similar to the eggs of most other petrels. They vary in shape from elongate pyriform to ovate. The average weight of the entire egg when fresh is about 4 oz.[4]

Moulting occurs in the Westland petrel in their non-breeding season between October and February, during migration to South America.[8] The immature birds moult prior to older individuals.[9]

Distribution and habitat

The Westland petrel is endemic to New Zealand.[1] It spends the majority of its life at sea, only returning to land to breed, and breeds only in a small region of the West Coast of the South Island.[10] The breeding range covers an 8 kilometre wide strip between Barrytown and Punakaiki on the West Coast, specifically between the Punakaiki River and Waiwhero (Lawson) Creek.[11] This area comprises forest-covered coastal foothills within the Paparoa National Park, on other conservation land, or on land belonging to Forest And Bird.[7][10] There is also a breeding colony located on private land, where guided tours of the colony are available.[12]

However, the total area of all breeding colonies combined is only about 0.16 km2 (0.062 sq mi).[9]

During the breeding season adults may be seen in waters around New Zealand from Cape Egmont to Fiordland in the west, through the Cook Strait, and from East Cape to Banks Peninsula in the east. They also range across areas of the Pacific Ocean and Tasman Sea around the subtropical convergence.[7] In the non-breeding season, Westland petrels migrate east to South American waters and feed in the Humboldt Current. They are often found off the coast of Chile.[9][13] Individuals usually remain solitary during this time, rejoining the colony when the next breeding cycle begins.[9]

Breeding and life-cycle

The Westland petrel is one of very few petrel species that still nest on the mainland.[1] Their large size and aggressive behaviour have helped to ensure that they can resist predators that would attack smaller species.[14] Westland petrels nest in burrows dug 1 to 2 metres into the hillside, often on a steep slope.[15] There are around 29 colonies of petrel in the breeding territory. Each colony has between 50 to 1000 burrows.[10] Colonies can be located anywhere from 50 to 200 metres above sea level.[9]

Westland petrel are winter breeders, arriving at their breeding grounds annually in late March or early April to prepare their burrows for nesting. Colonies are noted to be very vocal around three weeks before nesting, during the time when courtship and mating occur.[16][17] Petrels can form life time pair-bonds.[15] The female lays a single egg between May and June that hatches two months later, between August and September. Both the male and female taking turns incubating the egg. After hatching, the parents care for the chick for about two weeks. After this time the chick is left alone, but is fed at night. If either parent dies, the breeding attempt will fail.[9] Fledging occurs between 120 and 130 days after hatching. The earliest fledging is in early November, with a peak around 20 November, and last in mid-January.[18][19] In total, chick rearing takes between two and four months.[13] After leaving the nesting sites, fledglings may not return for up to 10 years.[20]

Diet and foraging

Petrels are nocturnal and hunt at night, preying primarily on fish, some squid, and less commonly on crustaceans.[21][13][7] Westland petrels are known to opportunistically scavenge fish from waste discarded by hoki fisheries during their breeding season as it overlaps with the fishing season, switching back to natural foraging at other times.[22][21] They capture their prey by surface seizing, surface diving, and, less frequently, pursuit plunging.[9] They have been recorded diving up to 8 metres (26 ft).[21] Their strong vision allows them to spot prey, and recent studies have shown that smell is also important to petrel foraging, specific odors seeming to attract the birds to certain areas.[13]

Threats

Breeding colony hazards

Westland petrels, along with other types of seabird exhibit natal philopatry - they return to their natal colony to breed. This means that the loss of a breeding colony through landslides, predation or human interference can have severe consequences for the population.

Storm, landslide and tree fall

The breeding colonies are often on steep sites, and are vulnerable to damage resulting from landslips and tree fall. In April 2014, Cyclone Ita brought very strong winds to the West Coast along with heavy rain. The storm caused widespread damage across the area of the breeding colonies, although not all colonies were equally affected. After the storm, a survey was conducted at colony locations containing 75% of the estimated breeding population. In 4 out of the 6 colonies surveyed, over half of the breeding habitat had been lost through landslips and fallen trees.[23]

Further damage to nesting areas occurred during Cyclone Fehi and Cyclone Gita in 2018.[24]

Predation

Predation by feral pigs and vagrant dogs are amongst the top threats to Westland petrels at the beeding colonies. Pigs are a particularly serious threat because they have the potential to destroy an entire nesting colony. There have been occasional reports that hunters have deliberately released pigs in areas close to the colonies. Wandering dogs are also a significant threat, because the settlement of Punakaiki is only 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) from the colonies.[9]

Other predators such as stoats,and rats and weka may strike during the breeding season when the birds are on land, preying on chicks in burrows and on adult birds.[17] Feral cats are also infrequent predators of petrels.[9] While not predators, concerns have been raised about the threat of burrow destruction by cattle and goats.[13] They can trample burrows and allow access to predators such as weka, that wouldn't have been able to reach them otherwise.

Threats from artificial lighting

Many types of seabirds are vulnerable to injury and death as a result of being attracted to artificial lights at night. This is a particular threat for petrels and shearwaters.[25] Burrow-nesting seabirds like the Westland petrel returning to their burrows at night can become disoriented by artificial lights and crash land on roads. They are often unable to take-off again. The birds can then be eaten by predators or struck by vehicles. In 2009, the Department of Conservation asked residents of Punakaiki to help reduce the occurrences od fledgling birds crash landing in the town by turning off outside lights and closing blinds at night, particularly during misty or stormy weather.[26] In 2020, the NZ Transport Agency (Waka Kotahi), in what was reported as a nationwide-first, turned off streetlights in Punakaiki between November and January, the period when the fledgling birds leave their burrows and take their first flight.[27] Shortly after the start of this conservation initiative, Westland petrels were found crash-landed in Greymouth, in larger numbers than reported in previous years. A recent switch to LED streetlights in Greymouth was suggested as a possible cause of the increase.[28] In 2021, it was reported that the number of birds crashing in Punakaiki had reduced significantly in response to the reduced lighting in the town, and the streetlights were again switched off during the next petrel fledging season.[29]

Parasites and diseases

Little research has been done on disease and parasites in New Zealand seabirds, and there are no diseases recorded to have significance with Westland petrels so far. Avian pox may potentially pose a threat to the petrels, as it has killed a number of black petrel chicks.[9] Other diseases affecting seabirds have been found such as avian cholera in rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes filholi), and avian diphtheria and avian malaria in yellow-eyed penguins (Megadyptes antipodes), none of which have been associated with Westland petrels.

Other threats

Power lines have caused the deaths of adult petrels from collision during flight. They are dangerous because they attract the birds and cause disorientation, largely in young petrels. This leads to petrels being grounded, which is a significant issue due to the way that Westland petrels must take flight. When the time comes to leave their breeding sites high in the foothills, Westland petrels climb up the tall trees and throw themselves off to fly. With early grounding, oftentimes the birds will perish from starvation, dehydration, predation, or collision with manmade structures.[9]

Commercial fishing produces competition for food, and sometimes petrels are accidentally captured in fishing nets. This is a prominent risk for Westland petrels due to their tendency to forage from commercial fishery waste, so they are known to interact closely with these vessels.[9]

Conservation

As of 2021, this species is regarded as being endangered under the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species.[1] The Department of Conservation assessed its conservation status in 2021 as "At Risk: Naturally Uncommon" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[2]

Relationship with humans

Tāiko festival

Every year, a festival is held in Punakaiki to celebrate the return of the petrel to its only known breeding sites, close to the town. It is a weekend-long festival in April that includes live music, various entertainment activities, and a local market. The festival begins with a viewing of the birds as they fly overhead and make their way to their nests in the mountains at dusk.[30]

Harvesting of chicks

Westland petrel chicks have historically been harvested for food in a practice known as muttonbirding, although this is not thought to be part of traditional Māori food gathering practice in this area.[18]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Procellaria westlandica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22698155A132629809. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22698155A132629809.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "Procellaria westlandica Falla, 1946". nztcs.org.nz. 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Norman, Geoff. Birdstories : a history of the birds of New Zealand. Nelson, New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-947503-92-5. OCLC 1045734859. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Robert Alexander Falla (1946). "An undescribed form of the black petrel". Records of the Canterbury Museum. 5: 111–113. ISSN 0370-3878. Wikidata Q110817358.

- Park, Geoff. (1995). Ngā uruora = The groves of life : ecology and history in a New Zealand landscape. Wellington, N.Z.: Victoria University Press. ISBN 0-86473-291-0. OCLC 34798269. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "tāikoPlay". Māori Dictionary. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Heather, Barrie; Robertson, Hugh (2015). The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-143-57092-9.

- Warham, John (1990). The petrels : their ecology and breeding systems. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-735420-4. OCLC 21976122.

- Susan M. Waugh; Kerry-Jayne Wilson (15 October 2017). "Threats and threat status of the Westland Petrel Procellaria westlandica" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 45: 195–203. ISSN 1018-3337. Wikidata Q110816456. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2020.

- GC Wood; HM Otley (September 2013). "An assessment of the breeding range, colony sizes and population of the Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 40 (3): 186–195. doi:10.1080/03014223.2012.736394. ISSN 0301-4223. Wikidata Q110816570. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022.

- "Westland petrel/tāiko". www.doc.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Steenhart, Josie (18 December 2016). "Weekender: Wild luxury in Punakaiki". Stuff. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Landers, T. (2012). The behavioural ecology of the threatened Westland Petrel (Procellaria westlandica): from colonial behaviours to their migratory and foraging ecology. Masters thesis. The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

- "Westland petrel". West Coast Penguin Trust. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Waugh, S. M.; Bartle, J.A. (2013). "Westland petrel". nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Allan J. Baker; J. D. Coleman (December 1977). "The breeding cycle of the Westland Black Petrel (Procellaria westlandica)" (PDF). Notornis. 24: 211–231. ISSN 0029-4470. Wikidata Q110816542. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2021.

- J.R. Jackson (1958). "The Westland Petrel" (PDF). Notornis. 7: 230–233. ISSN 0029-4470. Wikidata Q110816802. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2021.

- Wilson, Kerry-Jayne (June 2016). "A review of the biology and ecology and an evaluation of threats to the Westland petrel Procellaria westlandica" (PDF). West Coast Penguin Trust. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- H. A. Best; K. L. Owen (1976). "Distribution of breeding sites of the Westland black petrel (Procellaria westlandica)" (PDF). Notornis. 23: 233–242. ISSN 0029-4470. Wikidata Q110816999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2021.

- Brinkley, ES; Howell, SNG; Force, MP; Spear, LB; Ainley, DC (2000). "Status of the Westland Petrel (Procellaria westlandica) off South America" (PDF). Notornis. 47: 179–183. ISSN 0029-4470. Wikidata Q110816692. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2021.

- Freeman, Amanda N. D. (1998). "Diet of Westland Petrels Procellaria westlandica: the Importance of Fisheries Waste During Chick-rearing". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 98:1: 36–43. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020 – via tandfonline.

- Amanda N. D. Freeman; Kerry-Jayne Wilson (2002). "Westland petrels and hoki fishery waste: opportunistic use of a readily available resource?" (PDF). Notornis. 49: 139–144. ISSN 0029-4470. Wikidata Q110816822. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2021.

- S.M. Waugh, T, Poutart, K-J Wilson. "Storm damage to Westland petrel colonies in 2014 from cyclone Ita" (PDF). Notornis. 2015, Vol. 62: 165–168. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - S.A. Waugh; C. Barbraud; K. Delord; K. Simister; G.B. Baker; G.K. Hedley; K-J Wilson; D.R.D. Rands (10 October 2020). "Trends in density, abundance, and response to storm damage for Westland Petrels Procellaria westlandica, 2007-2019" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 48: 273–281. ISSN 1018-3337. Wikidata Q110823653. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2022.

- Airam Rodríguez; Nick D Holmes; Peter G Ryan; et al. (17 May 2017). "Seabird mortality induced by land-based artificial lights". Conservation Biology. 31 (5): 986–1001. doi:10.1111/COBI.12900. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 28151557. Wikidata Q38984539.

- "DOC asks for help with petrels". The West Coast Messenger. 9 December 2009.

- Joanne Naish, Joanne Naish (3 November 2020). "West Coast village going dark to save baby seabirds blinded by street lights". Stuff. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Naish, Joanne (21 December 2020). "Westland Petrels crashing in Greymouth after lights go out in Punakaiki". Stuff. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Mills, Laura (27 October 2021). "Darkness planned to help birds". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- "Taiko festival 7-8 May: something wonderful for everyone". West Coast Penguin Trust. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Procellaria westlandica. |

- Westland petrel – tāiko at Department of Conservation

- Westland petrel – tāiko at West Coast Penguin Trust

- Westland petrel – tāiko at Paparoa Nature Tours

- Photos and fact file – ARKive

- Tāiko Festival information