Patriot War (Florida)

The Patriot War was an attempt in 1812 to foment a rebellion in Spanish East Florida with the intent of annexing the province to the United States. The invasion and occupation of parts of East Florida had elements of filibustering, but was also supported by units of the United States Army, Navy and Marines, and by militia from Georgia and Tennessee. The rebellion was instigated by General George Mathews, who had been commissioned by United States President James Madison to accept any offer from local authorities to deliver any part of the Floridas to the United States, and to prevent the occupation of the Floridas by Great Britain. The rebellion was supported by the Patriot Army, which consisted primarily of citizens of Georgia. The Patriot Army, with the aid of U.S. Navy gunboats, was able to occupy Fernandina and parts of northeast Florida, but never gathered enough strength to attack St. Augustine. United States Army troops and Marines were later stationed in Florida in support of the Patriots. The occupation of parts of Florida lasted over a year, but after United States military units were withdrawn and Seminoles entered the conflict, the Patriots dissolved.

Background

Before 1803

Conflict between Spain and the United States over the status of East and West Florida arose during the American Revolutionary War. Leaders of the American Revolution hoped that all of British North America, including Canada, the Floridas, and even Bermuda, would become part of the United States.[lower-alpha 1] Spain joined its ally France in the war in support of the United States against Britain in 1779, but did not officially recognize the United States or enter into a treaty with it before the end of the war. Spain wanted to recover Florida and all of Luisiana Oriental (the part of French Louisiana between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River up to the Ohio River) and have exclusive control and use of the Mississippi River. The United States wanted possession of all territory east of the Mississippi River, including the Floridas, and free navigation on the Mississippi. In the event that Spain recovered Florida, the United States wanted access to a free port on the Gulf of Mexico.[3]

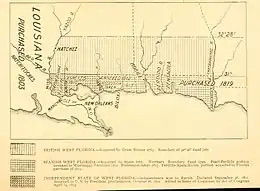

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War, returned the Floridas to Spain, awarded the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River north of the 31st parallel to the United States, and gave the United States navigation rights on the Mississippi. Spain rejected the last two provisions of the treaty, closing the Mississippi to American navigation in 1784, and claiming boundaries for West Florida that were further east (the Flint River) and further north (the mouth of the Ohio River) than specified in the Treaty of Paris. Further irritants in relations between the United States and Spain included the policies of the Florida and Louisiana colonies in welcoming American settlers, and Spanish support for Indian tribes in the United States. The United States and Spain finally negotiated a treaty in 1795. Pinckney's Treaty settled the boundary between the United States and Louisiana on the Mississippi River, and the northern boundary of West Florida on the 31st parallel between the Chattahoochee River and the Mississippi. Spain also conceded navigation on the Mississippi and the "right of deposit" (storage of goods awaiting export) in New Orleans to the United States as a "privilege" rather than a right.[4]

In 1800 France regained Louisiana from Spain through the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. The treaty ambiguously described "the Colony or Province of Louisiana with the same extent that it now has in the hands of Spain, and that it had when France possessed it; and such as it should be after the Treaties subsequently entered into between Spain and other states."[5] Prior to 1763 France had claimed all of the coast along the Gulf of Mexico from the Perdido River to the Rio Grande as part of Louisiana, i.e., from Mobile to southern Texas. France clearly specified that it wanted the area between New Orleans and Mobile Bay included in Louisiana when it was returned. France also wanted to acquire East Florida from Spain. Spain ceded control of the Isle of Orleans and of Louisiana west of the Mississippi to France, but continued to administer all of West Florida to the Mississippi River.[6]

After the Louisiana Purchase

In order to obtain a port on the Gulf of Mexico with secure access for Americans, United States diplomats in Europe were instructed to try to purchase the Isle of Orleans and West Florida from whichever country owned them. When Robert Livingston approached France in 1803 about buying the Isle of Orleans, the French government offered to sell it and all of Louisiana, as well. While the purchase of Louisiana exceeded their instructions, Livingston and James Monroe (who had been sent to help Livingston negotiate the sale) believed that the purchase would include the area east of the Mississippi to the Perdido River, and had references to the appropriate clauses in the Treaty of San Ildefonso included in the purchase treaty. President Thomas Jefferson, after extensive research, concluded that the Louisiana Purchase included West Florida to the Perdido River, and gave the United States a strong claim to Texas.[7]

The American claim that West Florida west of the Perdido River was included in the Louisiana Purchase was rejected by Spain, and American plans to establish a customs house at Mobile Bay in 1804 were dropped in the face of Spanish protests, although the United States government still considered the claims to be valid. It also hoped to acquire all of the Gulf coast east of Louisiana, and plans were made to offer to buy the remainder of West Florida (between the Perdido and Apalachicola Rivers) and all of East Florida. It was soon decided, however, that rather than paying for the colonies, the United States would offer to assume Spanish debts to American citizens in return for Spain ceding the Floridas.[lower-alpha 2] The American position was that it was placing a lien on East Florida in lieu of seizing the colony to settle the debts.[9]

In 1808 Napoleon invaded Spain, forced Ferdinand VII, King of Spain, to abdicate, and installed his bother Joseph Bonaparte as King. Resistance to the French invasion coalesced in a national government, the Cádiz Cortes. This government then entered into an alliance with Great Britain against France. This alliance raised fears in the United States that Britain would establish bases in or occupy Spanish colonies, including the Floridas, gravely compromising the security of the southern frontiers of the United States.[10]

West Florida

By 1810, during the Peninsular War, Spain was largely overrun by the French army. Rebellions against the Spanish authorities broke out in many of its American colonies. Residents of westernmost West Florida (between the Mississippi and Pearl Rivers) organized a convention at Baton Rouge in the summer of 1810. The convention was concerned about maintaining public order and preventing control of the district from falling into French hands, and at first tried to establish a government under local control that was nominally loyal to Ferdinand VII. After discovering that the Spanish governor of the district had appealed for military aid to put down an "insurrection", militia seized the Spanish fort in Baton Rouge, and on September 26, the convention declared West Florida to be independent.[11]

The authorities of the newly proclaimed Republic appealed to the United States to annex the area, and to provide financial aid. On October 27, 1810 President James Madison proclaimed that the area had become a part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase, although the United States had refrained from expelling Spanish authorities pending peaceful arrangements for their withdrawal. At the same time, Governor William C. C. Claiborne of the Territory of Orleans was instructed to occupy the area and administer it as part of the Territory.[12][lower-alpha 3]

Settlers in West Florida and in the adjacent Mississippi Territory started organizing in the summer of 1810 to seize Mobile and Pensacola, the last of which was outside the part of West Florida claimed by the United States. United States authorities acted to suppress this filibustering. Juan Vicente Folch y Jaun, governor of West Florida, hoping to avoid fighting, abolished customs duties on American goods at Mobile, and offered to surrender all of West Florida to the United States if he had not received help or instructions from Havana or Veracruz by the end of the year.[13]

Special Agents

United States officials feared that France would overrun all of Spain, with the result that Spanish colonies would either fall under French control, or be seized by Great Britain. On June 20, 1810, Secretary of State Robert Smith wrote to Georgia Senator William H. Crawford and asked that he find someone who could travel to East Florida and gather information and spread word that if any settlers were to rebel against the Spanish, they would be welcome into the United States.[14] Crawford would eventually identify and recruit General George Mathews.[15] In January 1811 President Madison requested Congress to pass legislation authorizing the United States to take "temporary possession" of any territory adjacent to the United States east of the Perdido River, i.e., the balance of West Florida and all of East Florida. The United States would be authorized to either accept transfer of territory from "local authorities", or occupy territory to prevent it falling into the hands of a foreign power other than Spain. The resolution also appropriated $100,000 for "expenses as the President shall deem necessary."[16] Congress debated and passed, on January 15, 1811, the requested resolution in closed session, and provided that the resolution could be kept secret until as late as March 1812.[17]

Under the resolution, General Mathews, as well as Colonel John McKee, were given commissions and asked to help fulfill the purpose of the act; to bring Florida into United States control. George Mathews was a veteran of the Revolutionary War and had served as the Governor of Georgia. Colonel John McKee had served as a militiaman and as a Federal Indian Agent to the Choctaw.[18] He also served to carry letters between governor Folch and the federal government.[19]

During Mathews' reconnaissance in East Florida, he had tried to judge the willingness of settlers to break away from Spain. In particular, he initiated clandestine meetings with five leading East Florida settlers, men with military and financial influence in the state. These meetings led Mathews to believe that the settlers in East Florida would prefer to join the United States rather than be vassals of the British Crown or Napoleon Bonaparte, if he did in fact depose the Spanish regency.[20] Of those five men, one was John Houston McIntosh, an affluent land owner and eventual leader of the rebel Patriot group.[21] McIntosh, and other southerners, disliked and very much feared that Spanish Florida was a safe zone for escaped slaves. He said of Florida: “the whole province will be the refuge of fugitive slaves; and from thence emissaries can, and no doubt will be detached, to ring about a revolt of the black population in the United States.”[22] In order to stop slaves from having a southern escape route, McIntosh believed, like many other U.S. citizens, that Florida needed to be taken over.[23]

At some point in March or April of 1811, Mathews and McKee conducted an interviews with governor Folch, who had previously shown interest in ceding West Florida to the United States. However, by then, Folch had changed his mind for a number of reasons. For one, his situation was not so desperate as before, he had received both funds and political powers to reinforce his position in West Florida. He also believed that the occupation of Baton Rouge was an insult to Spain and turning over any more lands to the United States would only add to that insult. And finally, by this point, the French advances during the Peninsular War had largely been stopped and the British forces were now on the offensive.[24] With the Spanish regency no longer in such a dire situation, Folch felt more confident in his position in Florida. Believing there was nothing to be done, McKee left the area and went back over the border to Fort Stoddert.[25][26]

Mathews, with diplomacy off the table, decided to turn his attentions more towards a military takeover. By March of 1812, he had put together a force of 125 men, made up of volunteers and militia from Tennessee and Georgia as well as a few Spanish deserters. This group would call themselves the Patriots.[27][28]

Fomenting the Rebellion and the Capture of Fernandina

Even before Mathews managed to band together his group of Patriots, there was evidence of unrest in East Florida. In early January of 1811, a letter from George J. F. Clarke, deputy surveyor general of East Florida and a loyal subject of Spain, described a group of “invaders” from Georgia who had crossed over the border and camped out near Fernandina with the intent to destabilize or otherwise create havoc in the region. Two men were sent into their camp to confront the group and it was discovered that they were under the orders of Major James Seagrove, commanding U.S. officer at Point Peter, Georgia, a military post about five miles from Amelia Island, Florida. When questioned about the situation, Seagrove openly admitted that his work with the Patriots was a part of Mathews' plans for Florida.[29] This direct tie between the U.S. military and the Patriots group was an early indication of U.S. designs in the region.

By mid-March of 1812, the Patriots, along with five U.S. gunboats, had managed to capture the town of Fernandina.[30]

Notes

- Spain received that part of Louisiana west of the Mississippi and the Isle of Orleans from France by the Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762.[1] Spanish Florida, along with that part of French Louisiana east of the Mississippi River (except for the Isle of Orleans) was transferred to Great Britain by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Britain organized the Florida territory into two colonies, East Florida and West Florida, adding the southern part of Louisiana east of the Mississippi to West Florida.[2]

- American claims against Spain arose from the use of Spanish ports by French warships and privateers that had attacked American vessels during the Quasi-War of 1798-1800.[8]

- The area has since been known as the Florida Parishes.

Citations

- Pugliese 2002, pp. 112–113.

- Borneman 2006, pp. 276–77.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 14–17.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 27–28, 31, 37.

- Stagg 2009, p. 39.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 39–41.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 40–41.

- Stagg 2009, p. 43.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 42–43.

- Cusick 2003, p. 14.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 58–67.

- Patrick 1954, pp. 11–12.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 80–86.

- Stagg 2007, p. 70.

- "Jackson, H. Mathews, George (1739-1812), soldier, frontiersman, and governor of Georgia". American National Biography. 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Phinney, A.H. (January 1926). "The First Spanish-American War". The Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 4 (3): 115. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- Stagg 2009, pp. 89–91.

- Lewis, Herbert J. "Jim". "John McKee". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Stagg 2007, p. 273.

- Cusick 2003, pp. 31–33.

- Cusick 2003, pp. 75.

- United States. Department of State., Wait, T. B. (Boston)., United States. President. (1819). State papers and publick documents of the United States, from the accession of George Washington to the presidency: exhibiting a complete view of our foreign relations since that time ... 3d ed. Boston: Printed and published by Thomas B. Wait. Retrieved from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081773586&view=1up&seq=11&skin=2021, pp 144-145

- Wasserman, Adam (2009). A People's History of Florida 1513-1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State (4th ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-1442167094.

- Southey, Robert (1828f). History of the Peninsular War. Vol. VI (New, in 6 volumes ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 2 May 2021, pp. 203-204

- Stagg 2007, p. 278.

- Pratt, J.W. (1925). Expansionists of 1812. Macmillan. p. 75.

- Kruse 1952, pp. 194–200.

- Cusick 2003, p. 83.

- Kruse 1952, pp. 200–203.

- Cusick 2003, pp. 107–111.

References

- Borneman, Walter R. (2006). The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-076184-4.

- Cusick, James G. (2003). The Other War of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of Spanish East Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8203-2921-5.

- Kruse, Paul (May 1952). "A Secret Agent in East Florida: General George Matthews and the Patriot War". The Journal of Southern History. 18 (2): 193–217. doi:10.2307/2954272. JSTOR 2954272.

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence Jr.; Smith, Gene A. (1997). Filibusters and Expansionists: Jeffersonian Manifest Destiny, 1800-1821. Tuscaloosa, Alabama and London: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5117-5.

- Patrick, Rembert W. (1954). Florida Fiasco: Rampant Rebels on the Georgia-Florida Border 1810-1815. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- Phinney, A.H. (January 1926). "The First Spanish-American War". The Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 4 (3): 115. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- Pratt, J.W. (1925). Expansionists of 1812. Macmillan.

- Pugliese, Elizabeth (2002). "Fontainebleau, Treaty of". In Junius P. Rodriguez (ed.). The Louisiana Purchase: a Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 1-57607-188-X.

- Smith, Joseph Burkholder (1983). The Plot to Steal Florida: James Madison's Phony War. New York: Arbor House.

- Southey, Robert (1828). History of the Peninsular War (Vol. V (New, in 6 volumes ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- Stagg, J. C. A. (Winter 2007). "George Mathews and John McKee: Revolutionizing East Florida, Mobile, and Pensacola in 1812". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 85 (3): 269–296. JSTOR 30150062.

- Stagg, J. C. A. (2009). Borderlines in Borderlands: James Madison and the Spanish-America Frontier, 1776-1821. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13905-1.