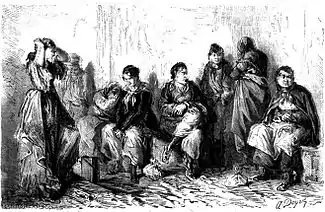

Pétroleuses

Pétroleuses were, according to popular rumours at the time, female supporters of the Paris Commune, accused of burning down much of Paris during the last days of the Commune in May 1871. During May, when Paris was being recaptured by loyalist Versaillais troops, rumours circulated that lower-class women were committing arson against private property and public buildings, using bottles full of petroleum or paraffin (similar to modern-day Molotov cocktails) which they threw into cellar windows, in a deliberate act of spite against the government. Many Parisian buildings, including the Hôtel de Ville, the Tuileries Palace, the Palais de Justice and many other government buildings were in fact set afire by the soldiers of the Commune during the last days of the Commune, prompting the press and Parisian public opinion to blame the pétroleuses.[1]

Trials and executions

Five women were put on trial for participation in the Commune, including the "Red Virgin" Louise Michel. She demanded the death penalty, but was instead deported to New Caledonia. She was pardoned in 1880 along with the other deportees and returned to France. Only a handful were convicted of any crimes, and their convictions were based on activity such as aiding the Commune soldiers. Only one woman was reported as executed by a firing squad during at the wall of Pere Lachaise cemetery, and it is not stated what her crime was. Official trial records show that no women were ever convicted of arson, and that accusations of the crime were quickly shown to have no basis. However, one pro-Commune participant and writer, Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray claimed that many working-class women were killed on site by Versaillais troops. He wrote, in his memoirs:

“Every woman who was badly dressed, or carrying a milk-can, a pail, an empty bottle, was pointed out as a pétroleuse, her clothes torn to tatters, she was pushed against the nearest wall, and killed with revolver-shots"[2]

He offered no evidence to support this claim of the mass execution of so-called Pétroleuses, and it was not supported or documented by more recent historians.

The Paris fires and the Myth of the Pétroleuse

During the Bloody Week at the end of the Commune, many Paris landmarks were set on fire by the Communards, most notably the Hotel de Ville, the Palais de Justice, the Tuileries Palace, the Palais d'Orsay, and other government building, as well as the commercial docks along the Seine and some private homes, including the residence of the writer Prosper Mérimée, who had died before the Commune, but was accused of supporting Napoleon III. Some later accounts blamed the fires on "petroleuses', or female arsonists. However, the history of the Paris Commune by Maxime Du Camp, written in the 1870s, and more recent research by historians of the Paris Commune, including Robert Tombs and Gay Gullickson, long ago debunked this myth and concluded that there were no incidents of deliberate arson by pétroleuses. The buildings destroyed at the end of the Commune were burned by the soldiers of the Commune, who proudly claimed credit for it afterwards. [3] The Commune soldiers, led by Paul Brunel, one of the original leaders of the Commune, took cans of oil and set fire to the Tuileries Palace, and buildings near the Rue Royale and the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Following the example set by Brunel, guardsmen set fire to dozens of other buildings on Rue Saint-Florentin, Rue de Rivoli, Rue de Bac, Rue de Lille, and other streets. Some buildings along the Rue de Rivoli were burned down during street-fighting between Communards and Versaillais troops. The arsonists also targeted the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris for burning. The furniture had been piled together inside the cathedral to start the fire, but the arson was cancelled when it was realised that the fire would inevitably spread to the neighbouring Hôtel-Dieu hospital, where hundreds of patients were sheltered.[4]

Regarding the Pétroleuses themselves, the negative connotation applied to the name was a prime result of the fear many men in higher ranks felt during the Paris Commune. The fear in question was that women could take advantage of the current revolution to alter gender norms and seek elevation in the societal hierarchy. As a result, news of Pétroleuses that were captured and punished was heavily publicized. It would serve as a warning to the remainder of French women that, "she would be killed as an example to other woman of what they could expect if they stepped out of the proper female role."[5]

References

- Robert Tombs, The War Against Paris: 1871, Cambridge University Press, 1981, 272 pages ISBN 978-0-521-28784-5

- Gay Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris, Cornell Univ Press, 1996, 304 pages ISBN 978-0-8014-8318-9

- Rougerie, Jacques, La Commune de 1871, (1988), Presses Universitaires de France, ISBN 978-2-13-062078-5.

- Oliver Lissagaray, The Paris Commune, (1876)

Notes and citations

- Rougerie, Jacques, La Commune de 1871, Presses Universitaires de France, (1988), p. 117.

- Oliver Lissagaray, The Paris Commune, (1876), p

- Zaretsky, Robert (2021-03-30). "The Paris Commune Lives on in French Politics: A Freighted Anniversary Becomes Talisman to Both Right and Left". Foreign Affairs.

- Lissagaray (1896) p. 338.

- Gullickson, Gay (1991). "La Pétroleuse: Representing Revolution". Feminist Studies. 17: 240–265 – via JSTOR.