Opus reticulatum

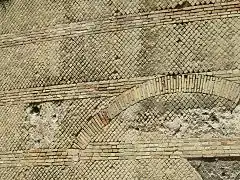

Opus reticulatum (also known as reticulated work) is a form of brickwork used in ancient Roman architecture. It consists of diamond-shaped bricks of tuff, referred to as cubilia,[1] placed around a core of opus caementicium.[2]

Opus reticulatum was generally used only in Italy with the exception of Africa because of tufa’s wider availability in Italy which made it easier to transport locally.[3] [4]There were some differences in construction overtime during the Augustan period the facing was covered with a veneer in Rome but this was rarely applied anywhere else.[5]

Name

Reticulatum is the Latin term for net-like, and opus, the term for a work of art, so the term translates to "net work". The diamond-shaped tufa blocks were placed with the pointed ends into the cement core at an angle of roughly 45 degrees, so the square bases formed a diagonal pattern, and the pattern of mortar lines resembled a net. The initial, rough form of opus reticulatum, an advancement from opus incertum, is called opus quasi reticulatum.

Uses

This construction technique was used from the beginning of the 1st century BC, and remained very common until opus latericium, a different form of brickwork, became more common.[2] Examples have even been found in Etruscan cities, such as Rusellae, wherein opus reticulatum is present around the entire perimeter of the Roman amphitheater. As worded by Michael Blömer:

The only examples of opus reticulatum known from the Near East are buildings commissioned by king Herod of Judea [in the baths of Herod's Third Winter Palace at Jericho[6]], the Tomb of Sampsigeramus, a local dynast of Emesa (Homs in Syria) in the 1st century CE and some early Roman monuments in Antioch (Antakya), which was the seat of the Roman governor of Syria.[7]

Opus reticulatum was used as a technique in the Renaissance Palazzo Rucellai in Florence, the skill having been lost with the end of the Roman Empire, and rediscovered by means of archeology by Leon Battista Alberti.

Gallery

Wall at Tivoli

Wall at Tivoli

Portion of a wall found near Hadrian's Villa

Portion of a wall found near Hadrian's Villa

See also

- Opus incertum – Ancient Roman masonry using irregular stones in a core of concrete

- Opus mixtum, also known as Opus compositum – Combination of Roman construction techniques

- Opus quadratum – Roman masonry using parallel courses of squared stone of the same height

- Roman concrete, also known as Opus caementicium – Building material used in ancient Rome

References

- "Nieuwe pagina 1". www.vitruvius.be.

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- Lancaster, Lynne C.; Ulrich, Roger B. (2013-10-11), "Materials and Techniques", A Companion to Roman Architecture, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 157–192, retrieved 2022-04-07

- Sear, Frank (2020-07-28), "Roman Architects, Building Techniques and Materials", Roman Architecture, Routledge, pp. 73–74, ISBN 978-1-351-00618-7, retrieved 2022-04-07

- Sear, Frank (2020-07-28), "Roman Architects, Building Techniques and Materials", Roman Architecture, Routledge, p. 78, ISBN 978-1-351-00618-7, retrieved 2022-04-07

- Ehud Netzer (1999). "Herodian bath-houses". In Janet DeLaine; David E. Johnston (eds.). Roman baths and bathing. p. 53. ISBN 9781887829373.

- Michael Blömer (2012). "Religious Life of Commagene in the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman Period". In Annette Merz; Teun Tieleman (eds.). The Letter of Mara bar Sarapion in Context: Proceedings of the Symposium Held at Utrecht University, 10–12 December 2009. p. 107. ISBN 9789004233010.