Monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule.[1] A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independent of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. Conversely, the opposition to monarchical rule is referred to as republicanism.[2][3][4]

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms of government |

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

Depending on the country, a royalist may advocate for the rule of the person who sits on the throne, a regent, a pretender, or someone who would otherwise occupy the throne but has been deposed.

History

Monarchical rule is among the oldest political institutions.[5] Monarchies have existed in some form since ancient Sumeria.[6] Monarchies often claimed legitimacy from a higher power (in early modern Europe the divine right of kings, and in China the Mandate of Heaven) and were the most common form of government until the 20th century, by which time republics had replaced many monarchies. Today forty-three sovereign nations in the world possess a monarch, including fifteen Commonwealth realms with Elizabeth II as their Queen and head of state.

Africa

In 1966, the Central African Republic was overthrown at the hands of Jean-Bédel Bokassa during the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état. He established the Central African Empire and ruled as Emperor Bokassa I until 1979, when he was subsequently deposed during Operation Caban and Central Africa returned to republican rule.

In 1974, one of the world's oldest monarchies was abolished in Ethiopia with the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie.

Asia

China possessed a monarchy from prehistoric times up until 1912, when Emperor Puyi was deposed. He was briefly restored to the throne for twelve days during the Manchu Restoration in 1917, but this was attempt was quickly undone by republican forces. The end of the Chinese monarchy ushered in the Republic of China.

Monarchism possessed an important role in the 1979 Iranian Revolution and also played a role in the modern political affairs of Nepal. Nepal was one of the last states to have had an absolute monarch, which continued until King Gyanendra was peacefully deposed in May 2008 and the country became a federal republic.

Europe

In England, royalty ceded power elsewhere in a gradual process. In 1215, a group of nobles forced King John to sign the Magna Carta, which guaranteed its barons certain liberties and established that the king's powers were not absolute. In 1687–88, the Glorious Revolution and the overthrow of King James II established the principles of constitutional monarchy, which would later be worked out by Locke and other thinkers. However, absolute monarchy, justified by Hobbes in Leviathan (1651), remained a prominent principle elsewhere. In the 18th century, Voltaire and others encouraged "enlightened absolutism", which was embraced by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II and by Catherine II of Russia.

In 1685 the Enlightenment began.[7] This would result in new anti-monarchist ideas[8] which resulted in several revolutions such as the 18th century American Revolution and the French Revolution which were both additional steps in the weakening of power of European monarchies. Each in its different way exemplified the concept of popular sovereignty upheld by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. 1848 then ushered in a wave of revolutions against the continental European monarchies.

World War I and the subsequent Interbellum

World War I and its aftermath saw the end of three major European monarchies: the Russian Romanov dynasty, the German Hohenzollern dynasty, including all other German monarchies and the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg dynasty.

Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary, the Republic of German-Austria was proclaimed. The Constitutional Assembly of German Austria passed the Habsburg Law, which permanently exiled the Habsburg family from Austria. Despite this, significant support for the Habsburg family persisted in Austria. Following the Anschluss, the Nazi Government suppressed monarchist activities. By the time Nazi rule ended in Austria, support for monarchism had largely evaporated.[9]

In Hungary, the rise of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 provoked an increase in support for monarchism; however, efforts by Hungarian monarchists failed to bring back a royal head of state, and the monarchists settled for a regent, Admiral Miklós Horthy, to represent the monarchy until it could be restored. Horthy was regent from 1920 to 1944. During Horthy's rule, attempts were made by Karl von Habsburg to return to the Hungarian throne, which ultimately failed. Following Karl's death, his claim to the Kingdom of Hungary was inherited by Otto von Habsburg, although no further attempts were made to seize the Hungarian throne.

In 1920s Germany a number of monarchists gathered around the German National People's Party which demanded the return of the Hohenzollern monarchy and an end to the Weimar Republic; the party retained a large base of support until the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, as Adolf Hitler was staunchly opposed to monarchism.

In Spain, the 1938 autocratic state of Francisco Franco claimed to have reconstituted the Spanish monarchy in absentia (and in this case ultimately yielded to a restoration, in the person of King Juan Carlos).

After World War II

With the arrival of socialism in Eastern Europe by the end of 1947, the remaining Eastern European monarchies, namely the Kingdom of Romania, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Albania, the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, were all abolished and replaced by socialist republics.

The aftermath of World War II also saw the return of monarchist and republican rivalry in Italy, where a referendum was held on whether the state should remain a monarchy or become a republic. The republican side won the vote by a narrow margin, and the modern Republic of Italy was created.

Monarchism as a political force internationally has substantially diminished since the end of the Second World War in Europe.

Current monarchies

The majority of current monarchies are constitutional monarchies. In most of these, the monarch wields only symbolic power, although in some, the monarch does play a role in political affairs. In Thailand, for instance, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who reigned from 1946 to 2016, played a critical role in the nation's political agenda and in various military coups. Similarly, in Morocco, King Mohammed VI wields significant, but not absolute power.

Liechtenstein is a democratic principality whose citizens have voluntarily given more power to their monarch in recent years.

There remain a handful of countries in which the monarch is the true ruler. The majority of these countries are oil-producing Arab Islamic monarchies like Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. Other strong monarchies include Brunei and Eswatini.

Justifications for monarchism

Absolute monarchy stands as an opposition to anarchism and, additionally since the Age of Enlightenment; liberalism, communism and socialism.

Otto von Habsburg advocated a form of constitutional monarchy based on the primacy of the supreme judicial function, with hereditary succession, mediation by a tribunal is warranted if suitability is problematic.[10][11]

Nonpartisan head of state and unifying force

British political scientist Vernon Bogdanor justifies monarchy on the grounds that it provides for a nonpartisan head of state, separate from the head of government, and thus ensures that the highest representative of the country, at home and internationally, does not represent a particular political party, but all people.[12] Bogdanor also notes that monarchies can play a helpful unifying role in a multinational state, noting that "In Belgium, it is sometimes said that the king is the only Belgian, everyone else being either Fleming or Walloon" and that the British sovereign can belong to all of the United Kingdom's constituent countries (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), without belonging to any particular one of them.[12]

Safeguard for liberty

The International Monarchist League, founded in 1943, has always sought to promote monarchy on the grounds that it strengthens popular liberty, both in a democracy and in a dictatorship, because by definition the monarch is not beholden to politicians.

British-American libertarian writer Matthew Feeney argues that European constitutional monarchies "have managed for the most part to avoid extreme politics"—specifically fascism, communism, and military dictatorship—"in part because monarchies provide a check on the wills of populist politicians" by representing entrenched customs and traditions.[13] Feeny notes that

European monarchies - such as the Danish, Belgian, Swedish, Dutch, Norwegian, and British - have ruled over countries that are among the most stable, prosperous, and free in the world.[13]

Socialist writer George Orwell argued a similar point, that constitutional monarchy is effective at preventing the development of Fascism.

"The function of the King in promoting stability and acting as a sort of keystone in a non-democratic society is, of course, obvious. But he also has, or can have, the function of acting as an escape-valve for dangerous emotions. A French journalist said to me once that the monarchy was one of the things that have saved Britain from Fascism...It is at any rate possible that while this division of function exists a Hitler or a Stalin cannot come to power. On the whole the European countries which have most successfully avoided Fascism have been constitutional monarchies...I have often advocated that a Labour government, i.e. one that meant business, would abolish titles while retaining the Royal Family.’[14]

Human desire for hierarchy

In a 1943 essay in The Spectator, "Equality", British author C.S. Lewis criticized egalitarianism, and its corresponding call for the abolition of monarchy, as contrary to human nature, writing,

A man's reaction to Monarchy is a kind of test. Monarchy can easily be 'debunked'; but watch the faces, mark well the accents, of the debunkers. These are the men whose tap-root in Eden has been cut: whom no rumour of the polyphony, the dance, can reach—men to whom pebbles laid in a row are more beautiful than an arch...Where men are forbidden to honour a king they honour millionaires, athletes, or film-stars instead: even famous prostitutes or gangsters. For spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison.[15]

Notable works

Notable works arguing in favor of monarchy include

|

|

Support for monarchy

Current monarchies

| Country | Polling firm/source | Sample size | Percentage of supporters | Date conducted | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government constitutional referendum | 17,782 | 52% | November 2018 | ||

| Newspoll | 1,639 | 41% | April 2018 | [16] | |

| IVOX | 1,000 | 58% | September 2017 | [17] | |

| Research Co. | 1,000 | 24% | February 2021 | [18] | |

| Gallup | 82% | 2014 | [19] | ||

| Jamaica Observer | 1,200 | 30% | 2020 | [20] | |

| Kyodo News | 83% | May 2019 | [21] | ||

| Afrobarometer | 75% | June 2018 | [22] | ||

| Le Monde | 1,108 | 91% | March 2009 | [23] | |

| EenVandaag | 26,000 | 56% | April 2022 | [24] | |

| Newshub-Reid | 48% | July 2022 | [25] | ||

| NRK | 81% | February 2017 | [26] | ||

| Government constitutional referendum | 52,262 | 56.3% | November 2009 | ||

| Platform for Independent Media | 3,000 | 34.9% | October 2020 | [27] | |

| Sifo | 65% | April 2016 | [28] | ||

| Suan Dusit Rajabhat University | 5,700 | 60% | October 2020 | [29] | |

| Government constitutional referendum | 1,939 | 64.9% | April 2008 | [30] | |

| YouGov | 4,870 | 61% | May 2021 | [31] |

Former monarchies

The following is a list of former monarchies and their percentage of public support for monarchism.

| Country | Polling firm/source | Sample size | Percentage of supporters | Date conducted | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [note 2] | [note 2] | 20%[note 2] | [note 2] | [32] | |

| University of the West Indies | 500 | 12% | November 2021 | [33] | |

| Círculo Monárquico Brasileiro | 188 | 32% | September 2019 | [34] | |

| Consilium Regium Croaticum | 1,759 | 41% | 2019 | [35] | |

| SC&C Market Research | 13% | 2018 | [36] | ||

| BVA Group | 953 | 17% | March 2007 | [37] | |

| Doctrina | 560 | 30% | July 2015 | [38] | |

| YouGov | 1,041 | 16% | April 2016 | [39] | |

| Kappa Research | 2,040 | 11.6% | April 2007 | [40] | |

| Azonnali | 3,541 | 46% | May 2021 | [41] | |

| GAMAAN | 14.6% | 2018 | [42] | ||

| Piepoli institute | 15% | 2018 | [43] | ||

| Parametría | 7.6% | July 2014 | [44] | ||

| Interdisciplinary Analysts | 3,000 | 49% | January 2008 | [45] | |

| Catholic University of Portugal/Diário de Notícias | 1,148 | 11% | March 2010 | [46] | |

| Institutul Român pentru Evaluare și Strategie | 1,073 | 21% | March 2016 | [47] | |

| Russian Public Opinion Research Center | ~1,800 | 28%[note 3] | March 2017 | [48] | |

| SAS Intelligence | 1,615 | 39.7% | April 2013 | [49] | |

| YouGov | 1,493 | 5% | April 2021 | [50] |

Notable Monarchists

Several notable public figures who advocated for monarchy or are monarchists include:

Thomas Aquinas, Italian Catholic priest & theologian[51]

Thomas Aquinas, Italian Catholic priest & theologian[51] Dante Alighieri, Italian poet & philosopher[52]

Dante Alighieri, Italian poet & philosopher[52]_-_MPM_V_IV_110_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Robert Filmer, English political theorist[54]

Robert Filmer, English political theorist[54].jpg.webp) Thomas Hobbes, English philosopher[55]

Thomas Hobbes, English philosopher[55]

.jpg.webp)

Joseph de Maistre, Savoyard philosopher & writer[59]

Joseph de Maistre, Savoyard philosopher & writer[59]

_Detail.jpg.webp) Honoré de Balzac, French novelist & playwright[61]

Honoré de Balzac, French novelist & playwright[61] Juan Donoso Cortés, Spanish politician and political theologian

Juan Donoso Cortés, Spanish politician and political theologian_-_(cropped).jpg.webp) Søren Kierkegaard, Danish philosopher & theologian[62]

Søren Kierkegaard, Danish philosopher & theologian[62].jpg.webp) Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor

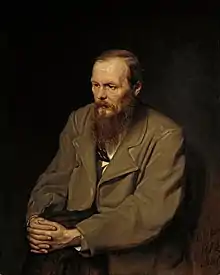

Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor Fyodor Dostoevsky, Russian novelist & essayist

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Russian novelist & essayist Miguel Miramón, Mexican President & military general

Miguel Miramón, Mexican President & military general Charles Maurras, French author & philosopher[63]

Charles Maurras, French author & philosopher[63] Kang Youwei, Chinese political thinker & reformer

Kang Youwei, Chinese political thinker & reformer Ralph Adams Cram, American architect & writer[64]

Ralph Adams Cram, American architect & writer[64]

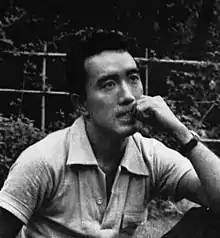

Yukio Mishima, Japanese author

Yukio Mishima, Japanese author.jpg.webp) Vernon Bogdanor, British political scientist & historian[67]

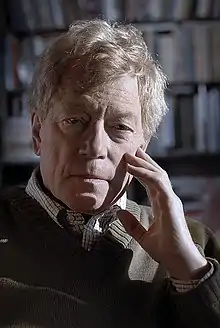

Vernon Bogdanor, British political scientist & historian[67] Roger Scruton, English philosopher & writer[68]

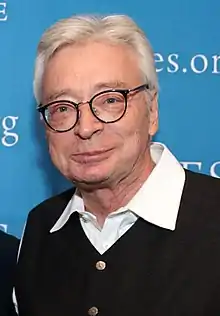

Roger Scruton, English philosopher & writer[68] Hans Hermann-Hoppe German-American political theorist[69]

Hans Hermann-Hoppe German-American political theorist[69]_(15621866127)_(cropped_2).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Stephen Fry, English actor & writer[72]

Stephen Fry, English actor & writer[72]

.jpg.webp) Carla Zambelli, Brazilian politician[75]

Carla Zambelli, Brazilian politician[75]

Antimonarchism

Criticism of monarchy can be targeted against the general form of government—monarchy—or more specifically, to particular monarchical governments as controlled by hereditary royal families. In some cases, this criticism can be curtailed by legal restrictions and be considered criminal speech, as in lèse-majesté. Monarchies in Europe and their underlying concepts, such as the Divine Right of Kings, were often criticized during the Age of Enlightenment, which notably paved the way to the French Revolution and the proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy in France. Earlier, the American Revolution had seen the Patriots suppress the Loyalists and expel all royal officials. In this century, monarchies are present in the world in many forms with different degrees of royal power and involvement in civil affairs:

- Absolute monarchies in Brunei, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Swaziland, the United Arab Emirates, and the Vatican City;

- Constitutional monarchies in the United Kingdom and its sovereign's Commonwealth Realms, and in Belgium, Denmark, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Monaco, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, and others.

The twentieth century, beginning with the 1917 February Revolution in Russia and accelerated by two world wars, saw many European countries replace their monarchies with republics, while others replaced their absolute monarchies with constitutional monarchies. Reverse movements have also occurred, with brief returns of the monarchy in France under the Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy, and the Second French Empire, the Stuarts after the English Civil War and the Bourbons in Spain after the Franco dictatorship.

See also

Notes

- Chapters LVIII-LXIV

- Figures for Austria is the average percentage of supporters from several opinion polls taken prior to November 2018; as reported by EFE.

- Among respondents, 22 per cent answered that they were not opposed to a monarchy in principle, but could not think of a person "worthy of the Russian throne", whereas 6 per cent believed there was.

References

- Webster's Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language, 1989 edition, p. 924.

- Bohn, H. G. (1849). The Standard Library Cyclopedia of Political, Constitutional, Statistical and Forensic Knowledge. p. 640.

A republic, according to the modern usage of the word, signifies a political community which is not under monarchical government ... in which one person does not possess the entire sovereign power.

- "Definition of Republic". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

a government having a chief of state who is not a monarch ... a government in which supreme power resides in a body of citizens entitled to vote and is exercised by elected officers and representatives responsible to them and governing according to law

- "The definition of republic". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

a state in which the supreme power rests in the body of citizens entitled to vote and is exercised by representatives chosen directly or indirectly by them. ... a state in which the head of government is not a monarch or other hereditary head of state.

- "Sumerian King List" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- "The Sumerian king list: translation". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- "Enlightenment". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- "A beginner's guide to the Age of Enlightenment (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- Wasserman, Janek (2014). "Östeneichische Aktion: Monarchism, Authoritarianism, and the Unity of the Austrian Conservative Ideological Field during the First Republic". Central European History. 47 (1): 76–104. doi:10.1017/S0008938914000636. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 43280409. S2CID 145335762.

- "Archived copy". home1.gte.net. Archived from the original on 10 February 2001. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Otto von Habsburg "Monarchy or Republic?". ("Excerpted from The Conservative Tradition in European Thought, Copyright 1970 by Educational Resources Corporation.")

- Bogdanor, Vernon (6 December 2000). "The Guardian has got it wrong". The Guardian.

- Feeney, Matthew (July 25, 2013). "The Benefits of Monarchy". Reason magazine.

- Orwell, George. Spring 1944 Partisan Review

- C.S. Lewis (26 August 1943). "Equality". The Spectator.

- The Australian. April 2018 https://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/prince-charles-aside-republic-opposition-rises-newspoll/news-story/87d0f10a77e601c2f028750af77aaefd.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Kwart van de Belgen wil republiek in plaats van monarchie". HLN.be. 17 September 2017.

- Canseco, Mario (1 March 2021). "Canadian Desire to Drop Monarchy Reaches Historic Level". ResearchCo.

- "What do the Danes think of their Royal Family and what role does the Danish Monarchy have?". YourDanishLife. 7 January 2022.

- "Queen's Commonwealth crumbling? Jamaica could be next country to ditch monarchy". Express. 19 March 2022.

- "Japan's New Emperor Naruhito Starts Reign at 83% Approval Rating". Bloomberg. 2 May 2019.

- "'We need the king!' Lesotho fed up with politicians' mistakes". TimesLive. 11 June 2018.

- "Government bans Le Monde opinion poll on royalty". 8 March 2009.

- "Support for Dutch royals slides, just 56% still support the monarchy". DutchNews.nl. 23 April 2022.

- Wade, Amelia (2 July 2022). "Newshub-Reid Research poll: Almost half of Kiwis want New Zealand to remain a monarchy after the Queen dies". Newshub.

- "80% of Norwegians support the monarchy". RoyalCentral.uk. 19 February 2017.

- Keely, Graham (12 October 2020). "Poll finds over 40% of Spaniards back republic in wake of royal scandals". Reuters.

- "Swedes want to retain the monarchy". Norway Today. 30 April 2016.

- Morris, James; Nyugen, Son (25 October 2020). "Strength of support for the monarchy being seen this week as political unrest deepens into standoff". Thai Examiner.

- "Tuvaluans vote against Republic". 30 April 2008.

- "Young British people want to ditch the monarchy, poll suggests". Reuters. 20 May 2021.

- "A century after Austrian-Hungarian Empire's fall, some nostalgic for monarchy". www.efe.com. EFE, S.A. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Survey shows support for republic". Barbados Today. 21 December 2021.

- "CMB Pesquisa de conhecimento e opinião pública" (in Portuguese). 27 September 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Thomas, Mark. "Two-fifths of Croatians want a return to the monarchy". www.thedubrovniktimes.com. The Dubrovnik Times. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Průzkum ke 100 rokům od vzniku Československa: kdyby se monarchie nerozpadla, měli bychom se lépe nebo stejně". iROZHLAS (in Czech). Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "BVA Group - Société d'études et conseil" (PDF). BVA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Kikacheishvili, Tamar (17 April 2017). "Georgia: Five-Year-Old Prince Prepares to Reign". eurasianet.org. Eurasianet. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Schmidt, Matthias (13 April 2016). "König(in) von Deutschland: Jeder Sechste wäre dafür". yougov.de (in German). YouGov. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Το ΒΗΜΑ onLine - ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΑ" (in Greek). 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 25 April 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "GYŐZTEK A HABSBURGOK: AZ AZONNALI OLVASÓINAK 46 SZÁZALÉKA ÚJRA KIRÁLYSÁGOT SZERETNE". azonnali.hu. 17 May 2021.

- Maleki, Ammar (August 2018). "The Findings of a Survey on Political Attitudes of Iranians by GAMAAN (The Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in IRAN)". doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.19332.37765. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Emanule Filiberto: "Politici? Sono dei parac***"". Occhio, il Savoia vuole fare il re" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "¿Qué opinan los mexicanos de la Monarquía?". Parametría (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- "In Nepal, Long-Lived Monarchy Fades From View". NY Times. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "Portugueses optam com clareza pela república" [Portuguese opt clearly for the Republic]. Diário de Notícias (in Portuguese). Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Victor, Lupu (25 April 2016). "Only 21 pc of Romanians want monarchy". www.romaniajournal.com. Romania Journal. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Galanina, Angelina (23 March 2017). "Россияне против монархии". Izvestia (in Russian). National Media Group. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Danas. "39 percent of Serbians in favor of monarchy, poll shows". b92. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "American Monarchy a Good Thing" (PDF). YouGov. 10 April 2021.

- Aquinas, Thomas. De Regno, to the King of Cyprus

- Alighieri, Dante. De Monarchia

- Bellarmine, Robert. On the Roman Pontiff.

- Filmer, Robert (1680). Patriarcha.

- Sommerville, J.P. (1992). Thomas Hobbes: Political Ideas in Historical Context. MacMillan. pp. 256–324. ISBN 978-0-333-49599-5.

- Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne. Politics Drawn from the Very Words of Holy Scripture

- Pius VI, Pourquoi Notre Voix

- Coulombe, Charles A. (2003). A History of the Popes: Vicars of Christ. MJF Books. p. 392.

- Beum, Robert (1997). "Ultra-Royalism Revisited," Modern Age, Vol. 39, No. 3, p. 305.

- Chateubriand. Of Buonaparte, and the Bourbons, and of the Necessity of Rallying Round Our Legitimate Princes

- "Balzac: A Fight Against Decandence and Materialism". Mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Garff, Joachim. Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography. p. 487.

- "Charles Maurras on the French Revolution · Liberty, Equality, Fraternity". Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Cram, Ralph Adams (1936). "Invitation to Monarchy".

- White, Steven F. (2020). Modern Italy's Founding Fathers: The Making of a Postwar Republic. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 108–109.

- Mammarealla, Giuseppe (1966). Italy After Fascism A Political History 1943–1965. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 114.

- Bogdanor, Vernon (6 December 2000). "The Guardian has got it wrong". The Guardian.

- "'A Focus of Loyalty Higher Than the State : The monarchy created peace in Central Europe, and its loss precipitated 70 years of conflict.' by Roger Scruton". Los Angeles Times. 1991-06-16.

- Hermann-Hoppe, Hans. Democracy: The God that Failed.

- "Monarhia salvează PSD. Tăriceanu şi Bădălău susţin un referendum pe tema monarhiei. Când ar avea loc acesta".

- Civil Georgia (2007-10-08). "Civil.Ge - Politicians Comment on Constitutional Monarchy Proposal". www.civil.ge.

- Stephen, Fry (30 June 2017). "Happy Birthday, America. One Small Suggestion". The New York Times.

- Pearlman, Johnathan (7 September 2013). "Ten things you didn't know about Tony Abbott". telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 19 Nov 2013.

- Johnson, Carol; Wanna, John; Lee, Hsu-Ann (2015). Abbott's Gambit: The 2013 Australian Federal Election. ANU Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-9250-2209-4.

- Viegas, Nonato (November 16, 2017). "Líder de movimento que pediu impeachment de Dilma agora é monarquista". ÉPOCA.

External links

- The Monarchist League

- IMC, official site of the International Monarchist Conference.

- SYLM, Support Your Local Monarch, the independent monarchist community.