MeToo movement in China

The MeToo movement (Chinese: #WoYeShi) emerged in China shortly after its origin in the United States.

In mainland China, online MeToo posts were slowed down due to censorship by the Chinese government.[1][2] Because of this, Chinese women began using the #MeToo hashtag on their social media, along with a combination of bunny, bowl, and rice emojis, a reference to the term "Rice bunny," pronounced in Chinese as "Mi-Tu". The idea of using the “rice (mi) bunny (tu)” emoji came from one of the feminist activists Xiao Qiqi.[3][4]

At universities

The #MeToo movement began in China in 2017 when Luo Qianqian (罗茜茜) accused Beihang University Professor Chen Xiaowu (陈小武) of having sexually harassed Luo in 2004 while she was a PhD candidate. While perusing Chinese question-and-answer site Zhihu, Luo saw other former students discussing Chen's improper behaviour, accusing him of sexual assault and saying he forced them to drink alcohol with him. One of the former students had recorded proof of the harassment. Luo then contacted the president of Beihang Alumni Association to accuse Chen publicly. Xiao Qiqi’s hashtag #MeToo on microblogging platform Weibo attracted more than 2.3 million views and the university removed Chen from his teaching position. China Daily praised the university's actions and encouraged students to continue exposing abusive teachers and professors.[2]

As the #MeToo movement gained more public attention, Li Tingting's partner Xiao Meili wrote an open letter denouncing the lack of proper investigation of sexual harassment on Chinese university campuses. Meili suggested universities offer education on sexual harassment to students, staff, and faculty through public lectures; that universities hire investigators; and establish hotlines for students to report sexual harassment directly to school officials.[5]

Peking University graduate Gu Huaying who wrote a joint letter to Peking University signed by 9,000 students asking the university to do more to prevent sexual harassment. The campaign faced pressure from the school authorities and social media censorship.

Professor Zhang Peng was removed from his teaching positions at Shanghai Normal University and Nanjing University when a #MeToo allegation accused him of raping one of his students while teaching at Peking University in 1998. The victim, 20-year-old sophomore Gao Yan, subsequently committed suicide.[6][7][8]

In 2022, Li Qi, a married professor at the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and doctor at the affiliated Shuguang Hospital, was fired by the university after its investigation into his affair with a master's student, who had an abortion after falling pregnant with his child. The same student also alleged that Li had affairs with other female students by promising to help them publish papers, find jobs, or study overseas.[9]

In the workplace

On the women’s labour rights website Jianjiaobuluo, an article was published by a female Foxconn assembly-line employee alleging they had experienced daily sexual harassment at the workplace, including dirty jokes about her body and unwanted physical contact. After the news of sexual harassment at Beihang University emerged, she demanded Foxconn on educating managers and employees about sexual harassment, and establish a hotline for reporting such sexual harassment, place anti-sexual harassment posters, and more. Her voice encouraged other female employees, especially those migrant workers and the undocumented rural workers.[10]

In 2017, Chinese female journalist Huang Xueqin went public with her own experience of workplace sexual harrasment. Her example encouraged similar reports to come out, and a number of university academics were punished as a result. She conducted a survey of mainland women journalists on the extent of sexual harassment in the industry and built an online platform for victims to share information, using the hashtag #WoYeShi. In August 2019, Her passport was confiscated after a six-month trip abroad. In October, she was arrested in Guangzhou on charges of "picking quarrels and provoking trouble", often used by police to detain activists. While Huang had shared photos of Hong Kong protesters, it was not clear whether her arrest was related.[11][12][13]

In religion

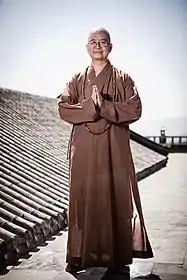

Reports emerged in 2018 of allegations of sexual misconduct by the abbot of Longquan Monastery, Shi Xuecheng. Two monks at Beijing Longhua Temple, Shi Xianxia and Shi Xianqi published a 95-page report online revealing the sexual harassment by their religious leader. According to their report, the abbot Shi Xuecheng sent sexually harassing text messages to a nun, Xianjia. Additionally, Shi Xuecheng sent sexually harassing texts to five other female disciples from Kek Lok Temple in Malaysia.[14] Two of them acted more defensively and rejected; however, four disciples ended up agreeing to the Shi Xuecheng's sexual demands after long hesitating. The report says that the female disciples were sexually harassed to become reliant on the abbot’s religious power. The Haidian district police received the alerts on this issue of sexual assault that happened at the temple in June 2018. Shi Xuecheng was also an official of the Chinese Communist Party, in charge of the government-run Buddhist Association. As a result of #MeToo, Shi Xuecheng lost his position as the abbot and is currently under investigation for sexual transgressions as a religious and political leader.[15]

In sports

On November 2, 2021, professional tennis player Peng Shuai shared allegations of sexual assault against Zhang Gaoli, former Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China and a high-ranked official of the Chinese Communist Party cadre.[16] Afterwards, Peng disappeared from public view in what was suspected to be a forced disappearance, and heavy censoring of her story by the Chinese government has not helped alleviate those apprehensions. State media appearances have led many to believe they were staged in fear of government reprisals. E-mails and publications have depicted her denying that she made the accusation of sexual assault. The incident has elicited international concern over Peng's safety, to the point the WTA suspended all events in China.[17][18]

Police intervention and government censorship

In 2015, a group of five Chinese feminists (Da Tu, Li Tingting, Wei Tingting, Wu Rongrong, and Wang Man) planned to distribute flyers on International Women’s Day to protest sexual harassment on public transportation. On March 7, the day before the planned protest, they were arrested and held in custody for the next 37 days for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”. The group became known as The Feminist Five. Da Tu mentioned that her feminist organization was reported to the police and forced to close, and that feminist performance art and public protest had almost impossible. She had been fighting sexual harassment in China since 2012; however, the public space for such activism drastically reduced since 2014 due to Chinese government censorship and police intervention. While in prison, Li Tingting was mocked for her lesbianism.[19]

References

- Hernandez, Javier C.; Mou, Zoe (January 23, 2018). "'Me Too,' Chinese Women Say. Not So Fast, Say the Censors". Archived from the original on February 1, 2018.

- Leta, Hong Fincher (2018). Betraying Big Brother: the feminist awakening in China, 1-32.

- Zeng, Meg Jing. "From #MeToo to #RiceBunny: how social media users are campaigning in China". The Conversation. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- "From #MeToo to #RiceBunny: Skirting social media censorship in China". ABC News. 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- Xiao Meili. "China Must Combat On-Campus Sexual Harassment: An Open Letter". SupChina, 8 January 2018. https://supchina.com/2018/01/08/china-must-combat-on-campus-sexual-harassment-an-open-letter.

- Xiao Meili, "Who Are the Young Women behind the '#MeToo in China' Campaign? An Organizer Explains", China Change, 27 March 2018, https://chinachange.org/2018/03/27/who-are-the-young-women-behind-the-metoo-in-china-campaign-an-organizer-explains.

- Mini Lau, "As #MeToo Movement Gains Traction in China, Professor is sacked 20 Years After Alleged Rape", South China Morning Post, 7 April 2018, www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2140724/chinese-professor-sacked-friends-suicide-victim-demand-apology-20.

- Javier C. Hernandez, "China's #MeToo: How a 20-Year-Old Rape Case Became a Rallying Cry", The New York Times, 9 April 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/09/world/asia/china-metoo-gao-yan.html

- Zuo, Mandy (25 February 2022). "#MeToo in China: academic fired after affair with student who fell pregnant". South China Morning Post.

- [I Am a Female Worker at Foxconn. I Am Asking for a System of Anti-Sexual Harassment] Jianjiaobuluo, 23 January 2018, www.jianjiaobuluo.com/content/11481

- Lau, "Police Detain Chinese #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin".

- "Police detain Chinese #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin". South China Morning Post. 24 October 2019.

- "Police detain Chinese #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin on public order charge". sg.news.yahoo.com.

- Shi Xianxia and Shi Xianqi, [A Report on a significant Situation], 4 -10

- "Chinese Monk Xuecheng Removed as Head of Beijing's Longquan Monastery Amid Sex Probe", Straits Times, 30 August 2018,https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/chinese-monk-xuecheng-removed-as-head-of-beijings-longquan-monastery-amid-sex-probe

- Myers, Steven Lee (3 November 2021). "A Chinese Tennis Star Accuses a Former Top Leader of Sexual Assault". The New York Times.

- "Peng 'must be heard' on sex abuse claim". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- Burgess, Annika. "Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai is the latest high-profile figure to disappear. She is unlikely to be the last". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- Zheng Churan (Da Tu), "Direct Activism".

Bibliography

- Fincher, Leta Hong. Betraying Big Brother, The Feminist Awakening in China. London: Verso, 2018.

- Javier C. Hernandez, "China's #MeToo: How a 20-Year-Old Rape Case Became a Rallying Cry", The New York Times, 9 April 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/09/world/asia/china-metoo-gao-yan.html

- Mimi Lau, "As #MeToo Movement Gains Traction in China, Professor is sacked 20 Years After Alleged Rape", South China Morning Post, 7 April 2018, www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2140724/chinese-professor-sacked-friends-suicide-victim-demand-apology-20.

- Mimi Lau, "Police detain Chinese #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin on public order charge",South China Morning Post, 24 October 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3034389/police-detain-chinese-metoo-activist-sophia-huang-xueqin-public

- Shi Xianxia and Shi Xianqi. [A Report on a Significant Situation].

- Straits Times. "Chinese Monk Xuecheng Removed as Head of Beijing's Longquan Monastery Amid Sex Probe". 30 August 2018. www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/chinese-monk-xuecheng-removed-as-head-of-beijings-longquan-monastery-amid-sex-probe.

- Xiao Meili. "China Must Combat On-Campus Sexual Harassment: An Open Letter". SupChina, 8 January 2018. https://supchina.com/2018/01/08/china-must-combat-on-campus-sexual-harassment-an-open-letter.

- Xiao Meili. "Who Are the Young Women Behind the '#MeToo in China' Campaign? An Organizer Explains". China Change, 27 March 2018, https://chinachange.org/2018/03/27/who-are-the-young-women-behind-the-metoo-in-china-campaign-an-organizer-explains.