Literary hostility to J. R. R. Tolkien

Between 1954 and the start of the 21st century, there was intense literary hostility to J. R. R. Tolkien, directed especially to his bestselling work The Lord of the Rings.

20th century critics such as Edmund Wilson, Edwin Muir, and Michael Moorcock attacked J. R. R. Tolkien's work as worthless and childish. Early in the 21st century, Judith Shulevitz, Jenny Turner, and Richard Jenkyns continued to find fault with The Lord of the Rings in particular.

From 1982, Tolkien scholars such as Tom Shippey and Verlyn Flieger began to roll back the hostility, defending Tolkien, rebutting the critics' attacks and analysing what they saw as good qualities in Tolkien's writing.

From 2003, scholars such as Brian Rosebury began to consider why Tolkien had attracted such hostility, noting that Tolkien avoided calling The Lord of the Rings a novel, and that in Shippey's view Tolkien had been aiming to create a medieval-style heroic romance, despite modern scepticism about that literary mode. In 2014, Patrick Curry analysed the reasons for the hostility, finding it both visceral and full of evident mistakes. Curry suggested that the issue was that the critics felt that Tolkien threatened their dominant ideology, modernism.

Context

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973) was an English Roman Catholic writer, poet, philologist, and academic, best known as the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.[1]

In 1954–55, The Lord of the Rings was published. In 1957, it was awarded the International Fantasy Award. The publication of the Ace Books and Ballantine paperbacks in the United States helped it to become immensely popular with a new generation in the 1960s. The book has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the twentieth century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[2] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the "Nation's best-loved book." In similar 2004 polls both Germany[3] and Australia[4] also found The Lord of the Rings to be their favourite book. In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium."[5] The popularity of The Lord of the Rings increased further when Peter Jackson's film trilogy came out in 2001–2003.[6]

Hostility

20th century

Some literary reviewers rejected Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings outright. In 1956, the literary critic Edmund Wilson wrote a review entitled "Oo, Those Awful Orcs!", calling Tolkien's work "juvenile trash", and saying "Dr. Tolkien has little skill at narrative and no instinct for literary form."[7]

In 1954, the Scottish poet Edwin Muir wrote in The Observer that "however one may look at it The Fellowship of the Ring is an extraordinary book",[8] but that although Tolkien "describes a tremendous conflict between good and evil ... his good people are consistently good, his evil figures immovably evil".[8] In 1955, Muir attacked The Return of the King, writing that "All the characters are boys masquerading as adult heroes ... and will never come to puberty ... Hardly one of them knows anything about women", causing Tolkien to complain angrily to his publisher.[9][10]

In 1969, the feminist scholar Catherine R. Stimpson published a book-length attack on Tolkien,[6] describing him as "an incorrigible nationalist", peopling his writing with "irritatingly, blandly, traditionally masculine" one-dimensional characters who live out a "bourgeois pastoral idyll".[11][6] This set the tone for other hostile critics.[12] Hal Colebatch[13][14] and Patrick Curry have refuted these charges.[6][12]

| Stimpson's charges | Curry's refutations |

|---|---|

| "An incorrigible nationalist", his epic "celebrates the English bourgeois pastoral idyll. Its characters, tranquil and well fed, live best in placid, philistine, provincial rural cosiness." | "Hobbits would have liked to live quiet rural lives – if they could have". Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry and Pippin chose not to do so. |

| Tolkien's characters are one-dimensional, dividing neatly into "good & evil, nice & nasty" | Frodo, Gollum, Boromir, and Denethor have "inner struggles, with widely varying results". Several major characters have a shadow; Frodo has both Sam and Gollum, and Gollum is in Sam's words both "Stinker" and "Slinker". Each race (Men, Elves, Hobbits) "is a collection of good, bad, and indifferent individuals". |

| Tolkien's language betrays "class snobbery". | In The Hobbit, maybe, but not in The Lord of the Rings. Even Orcs are of three kinds, "and none are necessarily 'working-class'". Hobbits are of varied class, and the idioms of each reflect that, as with contemporary humans. Sam, "arguably the real hero", has the accent and idiom of a rural peasant; the "major villains – Smaug, Saruman, the Lord of the Nazgûl (and presumably Sauron too) are unmistakably posh". "The Scouring of the Shire" is certainly (in Tolkien's words) "the hour of the [ordinary] Shire-folk". |

| "Behind the moral structure is a regressive emotional pattern. For Tolkien is irritatingly, blandly, traditionally masculine....He makes his women characters, no matter what their rank, the most hackneyed of stereotypes. They are either beautiful and distant, simply distant, or simply simple". | "It is tempting to reply, guilty as charged", as Tolkien is paternalistic, but Galadriel is "a powerful and wise woman" and like Éowyn is "more complex and conflicted than Stimpson allows". Tolkien "committed no crime worse than being a man of his time and place". And "countless women have enjoyed and even loved The Lord of the Rings". Scholars do not complain that Moby Dick says little on women and sex. |

The fantasy author Michael Moorcock, in his 1978 essay, "Epic Pooh", compared Tolkien's work to Winnie-the-Pooh. He asserted, citing the third chapter of The Lord of the Rings, that its "predominant tone" was "the prose of the nursery-room .. a lullaby; it is meant to soothe and console."[15][16]

21st century

The hostility continued until the start of the 21st century. In 2001, The New York Times reviewer Judith Shulevitz criticized the "pedantry" of Tolkien's literary style, saying that he "formulated a high-minded belief in the importance of his mission as a literary preservationist, which turns out to be death to literature itself."[17] The same year, in the London Review of Books, Jenny Turner wrote that The Lord of the Rings provided "a closed space, finite and self-supporting, fixated on its own nostalgia, quietly running down";[18] the books were suitable for "vulnerable people. You can feel secure inside them, no matter what is going on in the nasty world outside. The merest weakling can be the master of this cosy little universe. Even a silly furry little hobbit can see his dreams come true."[18] She cited the Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey's observation ("The hobbits ... have to be dug out ... of no fewer than five Homely Houses"[19]) that the quest repeats itself, the chase in the Shire ending with dinner at Farmer Maggot's, the trouble with Old Man Willow ending with hot baths and comfort at Tom Bombadil's, and again safety after adventures in Bree, Rivendell, and Lothlórien.[18] Turner commented that reading the book is to "find oneself gently rocked between bleakness and luxury, the sublime and the cosy. Scary, safe again. Scary, safe again. Scary, safe again."[18] In her view, this compulsive rhythm is what Sigmund Freud described in his Beyond the Pleasure Principle.[18] She asked whether, in his writing, Tolkien, whose father died when he was 3 and his mother when he was 12, was not "trying to recover his lost parents, his lost childhood, an impossibly prelapsarian sense of peace?"[18]

The critic Richard Jenkyns, writing in The New Republic in 2002, criticized a perceived lack of psychological depth. Both the characters and the work itself were, according to Jenkyns, "anemic, and lacking in fiber."[20] Also that year, the science-fiction author David Brin criticised the book in Salon as carefully crafted and seductive, but backward-looking. He wrote that he had enjoyed it as a child as escapist fantasy, but that it clearly also reflected the decades of totalitarianism in the mid-20th century. Brin saw the change from feudalism to a free middle class as progress, and in his view, Tolkien, like the Romantic poets, as opposed to that. As well as its being "a great tale", Brin saw good points in the work; Tolkien was, he wrote, self-critical, for example blaming the elves for trying to halt time by forging their Rings, while the Ringwraiths could be seen as cautionary figures of Greek hubris, men who reached too high, and fell.[21][22]

Jared Lobdell, evaluating the hostile reception of Tolkien by the mainstream literary establishment in the 2006 J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, noted that Wilson was "well known as an enemy of religion", of popular books, and "conservatism in any form".[9] Lobdell concluded that "no 'mainstream critic' appreciated The Lord of the Rings or indeed was in a position to write criticism on it – most being unsure what it was and why readers liked it."[9] He noted that Brian Aldiss was a critic of science fiction, distinguishing such "critics" from Tolkien scholarship, the study and analysis of Tolkien's themes, influences, and methods.[9]

Rebuttals

Defence

Alongside their analysis of Tolkien's work, scholars set about rebutting many of the literary critics' claims. For instance, starting with his 1982 book The Road to Middle-earth, Tom Shippey pointed out that Muir's assertion that Tolkien's writing was non-adult, as the protagonists end with no pain, is not true of Frodo, who is permanently scarred and can no longer enjoy life in the Shire. Or again, he replies to Colin Manlove's attack on Tolkien's "overworked cadences" and "monotonous pitch" and the suggestion that the Ubi sunt section of the Old English poem The Wanderer is "real elegy" unlike anything in Tolkien, with the observation that Tolkien's Lament of the Rohirrim is a paraphrase of just that section;[25] other scholars have praised Tolkien's poem.[26] As a final example, he replies to the critic Mark Roberts's 1956 statement that The Lord of the Rings "is not moulded by some vision of things which is at the same time its raison d'etre";[27] he calls this one of the least perceptive comments ever made on Tolkien, stating that on the contrary the work "fits together ... on almost every level", with complex interlacing, a consistent ambiguity about the Ring and the nature of evil, and a consistent theory of the role of "chance" or "luck", all of which he explains in detail.[28]

Brian Rosebury, a scholar of the humanities, considered why The Lord of the Rings has attracted so much literary hostility, and re-evaluated it as a literary work. He noted that many critics have stated that it is not a novel and that some have proposed a medieval genre like "romance" or "epic". He cited Shippey's "more subtl[e]" suggestion that "Tolkien set himself to write a romance for an audience brought up on novels", noting that Tolkien did occasionally call the work a romance but usually called it a tale, a story, or a history.[29] Shippey argued that the work aims at Northrop Frye's "heroic romance" mode, only one level below "myth", but descending to "low mimesis" with the much less serious hobbits, who serve to deflect the modern reader's scepticism of the higher reaches of medieval-style romance.[30]

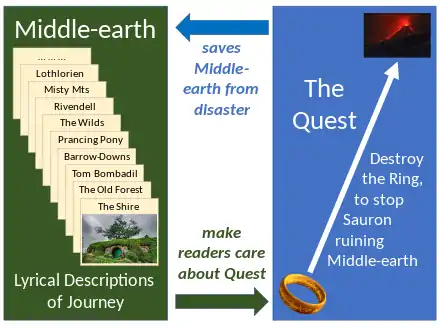

Rosebury noted that much of the work, especially Book 1, is largely descriptive rather than plot-based; it focuses mainly on Middle-earth itself, taking a journey through a series of tableaux – in the Shire, in the Old Forest, with Tom Bombadil, and so on. He states that "The circumstantial expansiveness of Middle-earth itself is central to the work's aesthetic power". Alongside this slow descriptiveness is the quest to destroy the Ring, a unifying plotline. The Ring needs to be destroyed to save Middle-earth itself from destruction or domination by Sauron. Hence, Rosebury argued, the book does have a single focus: Middle-earth itself. The work builds up Middle-earth as a place that readers come to love, shows that it is under dire threat, and – with the destruction of the Ring – provides the "eucatastrophe" for a happy ending. That makes the work "comedic" rather than tragic, in classical terms; but it also embodies the inevitability of loss, like the elves, hobbits, and the rest decline and fade. Even the least novelistic parts of the work, the chronicles, narratives, and essays of the appendices, help to build a consistent image of Middle-earth. The work is thus, Rosebury asserted, very tightly constructed, the expansiveness and plot fitting together exactly.[29]

Counter-attack

Patrick Curry, writing in A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien, stated that attempts at a balanced response, finding a positive critic for each negative one, as Daniel Timmons had done,[31] was "admirably irenic [peaceful] but misleading"[6] as this failed to address the reasons for the hostility. Curry noted that the attacks on Tolkien began when The Lord of the Rings appeared; increased when the work became "spectacular[ly] successful"[6] from 1965; and revived when readers' polls by Waterstones and BBC Radio 4 acclaimed the work in 1996–1998, and then again when Peter Jackson's film trilogy came out in 2001–2003. He noted Shippey's remark that the hostile critics Philip Toynbee and Edmund Wilson revealed "gross inconsistency between their self-professed critical ideals and their practice when they encounter Tolkien",[6] adding that Fred Inglis had called Tolkien a fascist and a practitioner of "'country-based fantasy' that is 'suburban' and 'half-educated".[6] Curry states that these criticisms are not simply demonstrably mistaken, but "rather how very (his emphasis) mistaken they are, and how consistently. That suggests that there is (as Marxists like to say) a structural or systematic bias at work".[6] He noted that Shippey's 1982 The Road to Middle-earth and then Verlyn Flieger's 1983 Splintered Light had slowly begun to reduce the hostility.[6] That did not prevent Jenny Turner from repeating "some of her predecessors' elementary mistakes"; Curry wrote that she seemed to fail to grasp "two of the most important things about art, literary or otherwise: that reality is (also) ineluctably fictional, and that fiction and its referents are (also) unavoidably real",[6] pointing out that metaphor is unavoidable in language.[6]

Summing up the attacks, Curry identified two consistent features: "a visceral hostility and emotional animus, and a plethora of mistakes showing that the books had not been read closely".[6] In his view, these derived from the critics' feeling that Tolkien threatened their "dominant ideology", modernism. Tolkien is, he wrote, modern but not modernist, at least as well-educated as the critics (another thing that made them feel threatened), and not ironic (especially about his writing). The Lord of the Rings is equally "a story told by a master story-teller; a story inspired by philology; a story suffused with Catholic values; and a mythic (or mythopoeic) story with a North European pagan inflection". In other words, Tolkien was about as anti-modernist as possible. Curry concluded by noting that newer authors including China Miéville, Junot Diaz, and Michael Chabon, and the critics Anthony Lane in The New Yorker and Andrew O'Hehir in Salon were taking a more open attitude, and cited the work's first publisher, Rayner Unwin's "pithy and accurate" assessment of it: "a very great book in its own curious way".[6]

References

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1978) [1977]. J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. Unwin Paperbacks. pp. 111, 200, 266 and throughout. ISBN 978-0-04928-039-7.

- Seiler, Andy (December 16, 2003). "'Rings' comes full circle". USA Today. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Diver, Krysia (5 October 2004). "A lord for Germany". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Cooper, Callista (5 December 2005). "Epic trilogy tops favourite film poll". ABC News Online. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- O'Hehir, Andrew (4 June 2001). "The book of the century". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2001. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Curry, Patrick (2020) [2014]. "The Critical Response to Tolkien's Fiction". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien (PDF). Wiley Blackwell. pp. 369–388. ISBN 978-1-11965-602-9.

- Wilson, Edmund (14 April 1956). "Oo, Those Awful Orcs! A review of The Fellowship of the Ring". The Nation. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Muir, Edwin (22 August 1954). "Review: The Fellowship of the Ring". The Observer.

- Lobdell, Jared (2013) [2007]. "Criticism of Tolkien, Twentieth Century". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Letters, #177 to Rayner Unwin, 8 December 1955

- Stimpson, Catharine (1969). J. R. R. Tolkien. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-03207-0. OCLC 24122.

- Curry, Patrick (2005). "Tolkien and the Critics: A Critique". In Honegger, Thomas (ed.). Root and Branch: Approaches Toward Understanding Tolkien (PDF) (2nd ed.). Walking Tree Publishers. pp. 83–85. Bibliography

- Colebatch, Hal (2003). Return of the Heroes: The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and Social Conflict (2nd ed.). Cybereditions. Chapter 6.

- Colebatch, Hal (2013) [2007]. "Communism". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Moorcock, Michael (1987). "RevolutionSF – Epic Pooh". RevolutionSF. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Moorcock, Michael (1987). "5. "Epic Pooh"". Wizardry and Wild Romance: A study of epic fantasy. Victor Gollancz. p. 181. ISBN 0-575-04324-5.

- Shulevitz, Judith (22 April 2001). "Hobbits in Hollywood". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Turner, Jenny (15 November 2001). "Reasons for Liking Tolkien". London Review of Books. 23 (22).

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. p. 65. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Jenkyns, Richard (28 January 2002). "Bored of the Rings". The New Republic. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Brin, David (17 December 2002). "J.R.R. Tolkien -- enemy of progress". Salon.com. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Brin, David (2008). The Lord of the Rings: J.R.R. Tolkien vs the Modern Age. Through Stranger Eyes: Reviews, Introductions, Tributes & Iconoclastic Essays. Nimble Books. part 1, "Dreading Tomorrow: Exploring our nightmares through literature", essay 3. ISBN 978-1-934840-39-9.

- Schürer, Norbert (13 November 2015). "Tolkien Criticism Today". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Baugher, Luke; Hillman, Tom; Nardi, Dominic J. "Tolkien Criticism Unbound". Mythgard Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 175, 201–203, 363–364. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Higgins, Andrew (2014). "Tolkien's Poetry (2013), edited by Julian Eilmann and Allan Turner". Journal of Tolkien Research. 1 (1). Article 4.

- Roberts, Mark (1 October 1956). "Essays in Criticism". 6 (4): 450–459. doi:10.1093/eic/VI.4.450.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. pp. 156–157 and passim. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Rosebury, Brian (2003) [1992]. Tolkien : A Cultural Phenomenon. Palgrave. pp. 1–3, 12–13, 25–34, 41, 57. ISBN 978-1403-91263-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 237–249. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Timmons, Daniel (1998). "J.R.R. Tolkien: The "Monstrous" in the Mirror". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 9 (3 (35) The Tolkien Issue): 229–246. JSTOR 43308359.

.jpg.webp)