Le Musée français

Le Musée français is a French publication of engravings issued in fascicles in Paris between 1803 and 1824. It had three successive titles, Le Musée français, Le Musée Napoléon and Le Musée royal, and consists of a total of 504 large-format engravings of paintings and classical sculptures along with commentaries and prefaces printed in letterpress, usually bound in six volumes. In library cataloging and bibliography, it has been treated as two separate publications, e.g., the catalogue of The Royal Academy of Arts (London): Le Musée français and Le Musée royal;[1][2] also: Jacques Charles Brunet, Manuel du libraire et de l'amateur de livres, 5e éd., t. 4 (Paris, 1863), cols. 1335-36 and t. 6, col.561, no. 9370; and Georges Vicaire, Manuel de l'amateur des livres du XIXe siècle (Paris, 1894–1910), vol. 5, cols. 1229–1231.

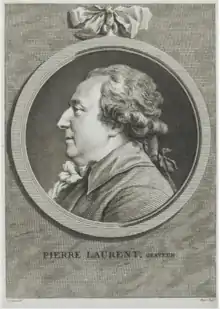

The project was initiated and directed by the engraver Pierre-François Laurent[3] with assistance and financial backing of his in-law Louis-Nicolas-Joseph Robillard de Péronville until 1809, when the two of them died and the direction passed to Laurent's son Henri, who was also an engraver.[4] Benefitting from a governmental loan signed personally by Bonaparte, the publication was restarted in 1812 in a new subscription with a second series of plates and a new title, Le Musée Napoléon.[5] Its issue was suspended at the collapse of the First French Empire; and when it resumed in 1817, this title was replaced by a third one, reflecting the new political regime, Le Musée royal; it continued to be directed by Henri Laurent, who received the official appointment "graveur du Cabinet du Roi"[6] from the new King Louis XVIII.

Le Musée français consists of four volumes issued between 1803 and 1812[7] containing 343 unnumbered plates, large in-folio; Le Musée royal consists of two volumes issued between 1812 and 1824 containing 161 unnumbered plates, large in-folio.[8] The plates were often exhibited by their engravers as individual art works at the Salons du Louvre; and they show a diversity of styles of engraving, employing burin with and without the assistance of etching and stipple,[9] as was practiced at this period in order to represent narrative painting, portraiture and landscape—and also classical sculpture—prior to the invention of photography.

Reception by contemporaries

It was one of several publications devoted to illustration of the paintings and classical sculptures seized by revolutionary governments for permanent display in the newly established Museum at the Louvre.[10] Le Musée français was specially esteemed for the large dimension of its engravings which were an occasion for display of the engraver's art; each would have required months or sometimes years to complete. Over 150 engravers from across Europe were employed in the production of the publication.[11] In official reports of the government, as well as in press reviews, its preparation was credited to have single-handedly revived the practice of burin engraving in France and become the source of "a great school" in its encouragement of the development of skills which were deemed important for the advancement of art and national commerce: the simulation of the qualities of highly regarded art works by means of print, in a manner suitable for the transmission of information, artistic inspiration and memorialisation.[12]

In the bibliographic literature it was commonly described as “collection magnifique.”[13] Brunet's repertory contains no work having a comparable quantity of large format, fully realized reproductive engravings;[14] and according to the official juries of the Exposition de 1806 and the Exposition de 1819, the quality of execution was "perfect".[15]

References

- "Le Musée Français, recueil complet des tableaux, statues et bas-reliefs, qui composent la collection nationale". Royal Academy.

- "Le Musée Royal ...ou Recueil de Gravures d'après les Plus Beaux Tableaux, Statues et Bas-reliefs de la Collection Royale". Royal Academy.

- "Pierre Francois Laurent (1739-1809)". Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 27 January 2022. See also Roger Portalis and Henri Beraldi, Les Graveurs du dix-huitième siècle, t. 2 (Paris, 1880-82), pp. 558-60.

- "Henri Laurent (1779-1844)". The British Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2022. Also Dictionnaire de biographie français, fasc. CXIV (2001), col. 1421-22.

- George McKee, "Une Mesure napoléonienne d'aide à la gravure", Nouvelles de l'estampe, no. 120 (déc. 1991), pp. 6-17.

- Dictionnaire du biographie français, fasc. CXIV (2001), col. 1421-22.

- The dates of publication of the fascicles are noted in the record of legal deposit of prints until 1811, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Est., Rés. Ye10 pet. in-fol. -- see the website Image of France. After 1811, the publication of fascicles was recorded in the Bibliographie de la France.

- For details about the history of the publication of these works, the catalogue of the Royal Academy of Arts, as noted above, refers to G. McKee, “The Musée français and the Musée royal: a history of the publication of an album of fine engravings, with a catalogue of plates and discussion of similar ventures,” MLS thesis, University of Chicago, 1981. The Musée français has also been studied by Caecilie Weissert, Ein Kunstbuch? le Musée français (Stuttgart: Engel, 1994) and Robert Verhoogt, “Art reproduction and the nation,” in Art crossing borders (Leiden, 2019), pp. 311-12; Italian contributors are discussed by Vittorio Sgarbi, et al., Felice Giani : maître du néoclassicisme italien à la cour de Napoléon (Alessandria, 2010); on contributions by the artist J.A.D. Ingres, see Sarah Betzer, “Ingres Shadows,” Art Bulletin, vol. 95 (2013), pp. 78-101. A good bibliography of other scholarship on the subject is provided by Peter Fuhring, at the Fondation Custodia website of Fritz Lugt, Les Marques des collections de dessins et d’estampes... L. 5021.

- E.g. Paul Chassard, Pausanais français, ou Description du Salon de 1806 (Paris, 1808), pp. 504-505 ; altogether 107 plates were exhibited at the Salons between 1804 and 1824 – see McKee, 1981, Appendice 4, pp. 141-43. Individual plates were often singled out for praise, as well, in press notices of the appearance of fascicles, e.g. Le Moniteur, 11 juin 1805 (p. 1084). A generous selection of examples treated as individual artworks may be examined with detailed catalogue information at the British Museum online catalogue.

- G. McKee, "The Publication of Bonaparte's Louvre", Gazette des Beaux-Arts, s. 6, t. 104 (nov. 1984), pp. 165-172. On the museum and its collections in this era, see Andrew McClellan, Inventing the Louvre: art, politics, and the origin of the modern museum in 18th centruy Paris (Berkeley: 2009) and Cecil Gould, Trophy of conquest: the Musee Napoleon and the creation of the Louvre (London, 1965).

- McKee, 1981, Appendix 6 and Appendix 7 contain a catalogue of the engravings and indexes of the artists who produced them.

- See official reports of the section des Beaux-Arts of the Institut by J. LeBreton, ”Notice des travaux de la Classe des Beaux-Arts, ” Nouvelles des arts, t. 4 (1804), p. 44 and C.C. Bervic, ”La Gravure, ” edited by U. van de Sandt, Rapports à l’Empereur sur le progrès des sciences, des lettres et des arts depuis 1789 [Paris: Belin, 1989], pp. 240-45 and ; the popular success is evident from journalism: Le Moniteur, 5 juin 1803 and 19 mars 1804; Journal de débats, 30 mai 1804 (p. 4); Mercure de France, 11 oct. 1806 (p. 88); Journal de Paris, 1 mars 1808 (p. 413); Journal de l’Empire, 30 août 1813. On the revival of “la gravure historique” in the early 19th century attributed to the influence of plates in this publication, see Georges Duplessis, Les Merveilles de la gravure (Paris, 1869), pp. 372-78.

- Brunet and Vicaire, as cited; also, Henri Cohen, Guide de l’amateur de livres à gravures du XVIIIe siècle, 6e éd. (Paris, 1912), cols. 743-45, ”magnifique ouvrage.”

- Cf. the bibliography of this kind of publication in Brunet, t. 6, “Table Méthodique,” cols. 561-64.

- McKee, 1991, p. 8, note 9; a judgement reiterated by the jury at the Exposition de 1819, paraphrased in Le Moniteur, 17 fév. 1824: “the most perfect to have occurred since the existence of the art of engraving.”