Lambert friction gearing disk drive transmission

The Lambert friction transmission (aka friction disk drive or friction-drive transmission) was a mechanism John W. Lambert came up with in 1904 and patented. The mechanical transmission consisted of a friction wheel pressed against the back of the automobile motor flywheel main disk by a pedal controlled by the driver's foot. It was a type of clutch by this function. When the pedal pressure was released altogether the friction wheel could be moved across the power flywheel disk to provide a different ratio to give a driving speed as high or as low as desired and even went into reverse for a brake or driving backwards. The transmission was used in all of the vehicles Lambert manufactured.

Development

The invention was a transmission for automobiles that had no toothed gears and instead was a friction disk drive that transferred the motor power to the wheels for propulsion. John W. Lambert saw the need for a smooth straightforward conveyance of automobile motor power to its drive wheels.[1] Some of Lambert's greatest difficulties encountered in attaining success for his gear-less friction disk drive transmission was the preconceived notion of the public that an automobile transmission had to have gears to operate correctly.[2] The friction disk drive (aka gearless device, traction drive) was a pivotal characteristic of the Union brand automobile and Lambert brand automobile that was manufactured through the Buckeye Manufacturing Company.[3][4][5]

Lambert is considered the father of the friction-drive transmission.[6] He started in 1900 to make the friction disk gearing drive transmission for the Union automobile. He first attempted a disk that was faced with leather and a friction wheel made out of iron. It had a diameter of eighteen-inches with a face that had a width of one and a half inches. With the first experiment the leather was burned in about 2.8 miles (4.5 km) of operating time. The disk Lambert then made was with a half inch thick wood fiber. The material had a polished lustrous surface and functioned as anticipated for awhile, but after 200 miles (320 km) of running it broke apart.[7][8]

Lambert continued with different experiments on the transmission to see if he could get better performance. One experiment involved piece of cast aluminum with a circular-shaped pointed end for a friction drive and he obtained outstanding performance as an outcome. It then occurred to him that the efficient transfer of energy was because of the aluminum. He then faced a disk with this metal and the rim of the traversing wheel that was at ninety degrees with a type of cardboard. This mechanical arrangement worked well for the vehicle engine power to get transferred to the driving wheels for propulsion. This chance discovery was good fortune for Lambert as it made his vehicles outstanding and outperformed other automobile manufactures that had similar friction type transmissions.[7][8]

Toothless gearing

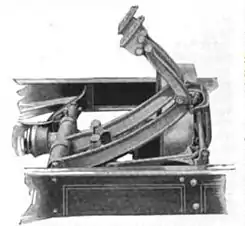

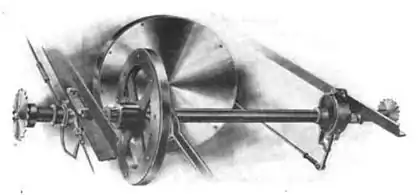

A large disk is connected directly to the automobile engine. A smaller disk of about half size was placed ninety degrees and the edge width of it rubbed up against the face of the large disk to obtain energy. The small disk was on an axle shaft that had chains at each end. Those chains went to the rear wheel axle that then propelled the vehicle.[9] The master aluminum disk was 21 inches in width and was plated with an aluminum disk facing of equal diameter and circumference size with a thickness of some five-sixteenth of an inch. The slave wheel that was at ninety degrees to the master disk was 18 inches in breadth with a working face of 1.5 inches (38 mm). This wheel had a fibrous material on it for friction grab. It was designed to slip on a sleeve and held on a steel shaft.[10]

The master flywheel disk or driving wheel from the automobile engine was overlaid with a disk facing of aluminum that could be replaced. The driven disk had a rim of elastic fiber of either paper or wood that was engaged and wore for about 3000 miles of driving before it had to be replaced.[11] Lambert found that the combination of aluminum and fibrous material bearing surfaces gave the maximum degree of traction efficiency and had a good sturdiness over time for wear on the materials. Toothed gears on the other hand had to be in very close contact with each other at all times to be efficient and not slip. That caused the friction surfaces of the teeth to be exposed to great strains and wore out the gears quicker than the friction drive transmission.[12][13]

Speed regulation

The speed adjustment was done by a mechanical device carrying a U-shaped rod to control the chiseled etched hub rim on the active propulsive wheel at one end by engaging it.[14] The other end of the metal link was to the accelerator and reversing lever controlled by the driver. The friction slave wheel disk is operated by the driver's foot pedal and friction is applied by the pressure that the driver applies. This forces the slave wheel rim into contact with the main motor flywheel disk transferring power onto this wheel's jack-shaft. When the driver no longer applies foot pressure a heavy duty spring automatically throws the slave disk back where it no longer is in contact with the main flywheel power disk.[14]

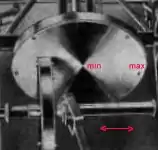

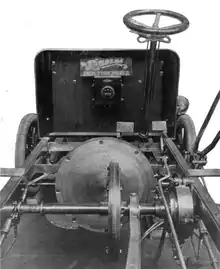

The slave wheel slids in each direction on the sleeve when disengaged from the master flywheel disk. All speeds for the vehicle, from the fastest (maximum) to the slowest (minimum), could be done in both directions, forward or backwards, depending on where the drive wheel was placed on the motor flywheel disk.[15] The Lambert friction transmission used side chains through sprockets that were on the same transverse jack-shaft as the drive disk.[14] The chains then went to the axle attached to the rear wheels that propelled the vehicle.[10] The premier characteristic of the Lambert brand automobile was the friction transmission disk drive speed controller that was a carry over feature from the manufacture of the Union brand automobile.[7]

The Buckeye Manufacturing Company had an advertising slogan of The Car With a Thousand Speeds for the Lambert automobiles it produced during the early part of the 1900s in its plant at Anderson, Indiana. It claimed the wide speed range was made possible through use of their friction transmission that Lambert designed. It also declared in one of its brochures of the time that there was no clashing of gears, no jerking and no jarring in starting the automobile moving. They further explained that there were no gears to grind or strip and no clutch to slip when the transmission was engaged.[16] It went on to say that in start up and all changes in speed were made so quietly and smoothly that the occupants of the car could not detect that the transmission had been engaged. They went on to say that any number of speeds forward or backward could be produced through the operation of a driver controller lever that moved the friction wheel across the face of the motor fly wheel that provided the vehicle propulsion.[17]

Patents

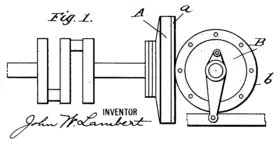

1904 invention

Lambert took out an application for a patent on his transmission apparatus which became officially No. 761,384 on May 31, 1904. The invention patent had six claims. The mechanism had a combination pair of shafts with disks that worked with each other. The main large disk that was driven off the automobile engine was faced with aluminum. The second disk was smaller and at 90 degrees to the main disk. This smaller disk had a fiber part on its rim and rubbed upon the aluminum faced driving-disk. The smaller disk was mechanically controllable as to the placement onto the radius of the powered disk. That placement controlled the speed of the automobile and could even be placed to make the car go in reverse.[18][19]

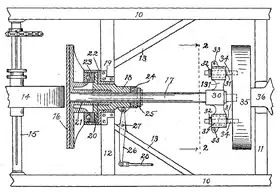

1910 invention

The 1910 modified invention No. 954,977 made further development to the 1904 patented friction driving structure and had mechanically improved features to make the transmission operate smoother. [20]

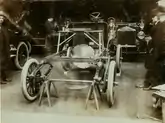

Lambert chassis showing the friction gearing transmission

Lambert chassis showing the friction gearing transmission The friction disk drive transmission in an assembly production line

The friction disk drive transmission in an assembly production line Friction disk drive transmission in Lambert automobile models 7 & 8

Friction disk drive transmission in Lambert automobile models 7 & 8

Success

Lambert first installed a gearless friction-drive transmission in an experimental 1898 gasoline driven horseless carriage automobile. He continued his experiments and had additional experimental automobiles in 1900 and 1901. He then produced the Union brand automobile with this type of transmission. He manufactured the Union automobile from 1902 through 1905 in Union City, Indiana. He manufactured the Lambert automobile from 1905 through 1916 in Anderson.[6]

The Lambert brand automobile developed from the Union automobile and was started to be manufactured in 1905. It also had the gearless friction-drive transmission. The transmission was used in all the vehicles that Lambert manufactured.[21] That included Lambert trucks,[22] fire engine vehicles, and agricultural farm tractors,[23] besides the various models of automobiles he produced. All of Lambert vehicles were produced through 1916. Their demise came about because of World War I and the manufacturing facilities converted to making military items. Lambert no longer made vehicles nor the friction transmission after the war.[3][24]

See also

| Automotive transmissions |

|---|

| Manual |

| Automatic / Semi-automatic |

Footnotes

- Forkner 2008, p. 383.

- "Lambert's work brings success". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. 22 March 1914. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Naldrett 2016, p. 73.

- Donald Sackheim and Robert Rosenberg (1968). Historic American Engineering Report / Buckeye Manufacturing Company / HAER IN-35 (Report). National Park Service. p. 2. Historic American Engineering record.

...a form of transmission which used friction plates in place of gears.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Loewenthal 1985, p. 4.

- "John W. Lambert". The Antique Automobile. 24: 344–346. 1960. ISSN 0003-5831. OCLC 1481611.

- Dolnar 1906, pp. 226–227.

- Fischer 1983, p. 83.

- "Each Model a Leader in Its Class". Cycle and Automobile Journal. 13: 106–107. 1909.

- Dolnar 1906, pp. 228–229.

- "The Lambert original friction drive". The San Francisco Call. San Francisco, California. 23 July 1911. p. 40 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Patents / 261, 384 Friction Gearing". The Horseless Age. 14: 48. 1904.

- "Lambert's friction transmission explained". Car & Parts. 18: 86. 1974.

- "Changing Lambert Name to Buckeye". Motor Age. 22: 40. 1912. OCLC 1776328.

- Trask, Charles A. (1918). "Friction Transmissions". The Journal of the Society of Automotive Engineers. Society of Automotive Engineers. 2 (6): 440–447.

- Larson 2008, p. 195.

- "Lambert Auto Labeled 'Car With 1,000 Speeds'". Anderson Daily Bulletin. Anderson, Indiana. 21 December 1967. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "761,384 Friction Gearing, John W. Lambert, Anderson - assignor to the Buckeye Manufacturing Company, Anderson Filed July 19 1902 Serial No 116,168". Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. 110: 1314. 1904.

- Dolnar 1906, pp. 226a.

- "954,977 Friction Driving Mechanism, John W. Lambert, Anderson, Indiana. Filed Jan 7 1909 No 471,055". Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. 153: 475. 1910.

- "Antique Truck 1912-ish Rare Unrestored Americana". TOPClassiccarsforsale.com. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- "Lambert Auto Truck". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. 20 May 1906. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Auto Tractor for Orchards will be made in this City". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. Los Angeles, California. April 20, 1912. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Scharchburg 1993, p. 25.

Sources

- Dolnar, Hugh (1906). "The Lambert, 1906 Line of Automobiles". Cycle & Automobile Trade Journal. 10 (7): 225–229.

- Forkner, John La Rue (2008). History of Madison County, Indiana. Bridgeport National Bindery. OCLC 712176620.

- Fischer, George K. (1983). Advanced Power Transmission Technology. NASA - AVRACOM TR-C-16 CP-2210. OCLC 1109595548.

- Larson, Len (2008). Dreams to Automobiles. McGraw Hill. ISBN 9781469101040.

- Loewenthal, Stuart H. (1985). Design of Traction Drives. NASA - Scientific and Technical Information Branch. OCLC 13590781.

- Naldrett, Alan (2016). Lost Car Companies of Detroit. Arcadia. ISBN 9781625856494.

- Scharchburg, Richard P. (1993). Carriages Without Horses. Society of Automotives Engineers. ISBN 1-56091-380-0.