Kingdom of Tungning

The Kingdom of Tungning (Chinese: 東寧王國; pinyin: Dōngníng Wángguó; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tang-lêng Ông-kok), also known as Tywan by the British at the time, was a dynastic maritime state that ruled part of southwestern Formosa (Taiwan) and the Penghu islands between 1661 and 1683. It is the first predominantly Han Chinese state in Taiwanese history. The kingdom was founded by Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) after seizing control of Taiwan, a foreign land outside China's boundaries, from Dutch rule. Zheng hoped to restore the Ming dynasty in Mainland China, when the Ming remnants' rump state in southern China was progressively conquered by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty. The Zheng dynasty used the island of Taiwan as a military base for their Ming loyalist movement which aimed to reclaim mainland China from the Qing. Under Zheng rule, Taiwan underwent a process of sinicization in an effort to consolidate the last stronghold of Han Chinese resistance against the invading Manchus. Until its annexation by the Qing dynasty in 1683, the kingdom was ruled by Koxinga's heirs, the House of Koxinga, and the period of rule is sometimes referred to as the Koxinga dynasty or the Zheng dynasty.[1][2][3]

Kingdom of Tungning | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1661–1683 | |||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||

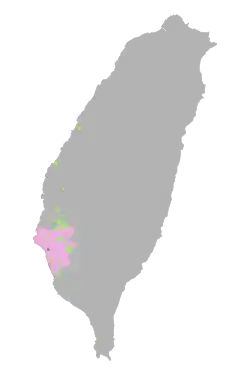

Location of the Kingdom of Tungning, and settlements

| |||||||||||

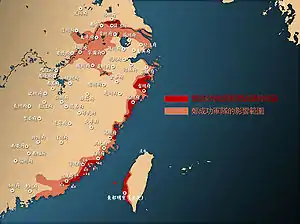

The territories ever controlled by the maritime force of Koxinga depicting in red, its historical sphere of influence shown in peach | |||||||||||

| Status | A princedom (郡王國) owing allegiance to the Southern Ming | ||||||||||

| Capital | Anping City (present-day Tainan) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Hokkien, Hakka, Formosan languages | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Prince of Yanping | |||||||||||

• 1661–1662 | Koxinga | ||||||||||

• 1662–1681 | Zheng Jing | ||||||||||

• 1681–1683 | Zheng Keshuang | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 14 June 1661 | ||||||||||

• Surrender to the Qing | 5 September 1683 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1664 | 140,000 | ||||||||||

• 1683 | 200,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Silver tael (Spanish dollar) and copper cash coin | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||

| Tungning | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 東寧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 东宁 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | East Peace | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭氏王朝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑氏王朝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng period of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 明鄭時期 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 明郑时期 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

At its peak, the kingdom's maritime power dominated varying extents of coastal regions of southeastern China, and its vast trade network stretched from Japan to Southeast Asia.

Names

In reference to its reigning house of Koxinga, the Kingdom of Tungning is sometimes known as the Zheng dynasty (Chinese: 鄭氏王朝; pinyin: Zhèngshì Wángcháo; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tēⁿ--sī Ông-tiâu), Zheng clan Kingdom (Chinese: 鄭氏王國; pinyin: Zhèngshì Wángguó; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tēⁿ--sī Ông-kok) or Yanping Kingdom (Chinese: 延平王國; pinyin: Yánpíng Wángguó; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Iân-pêng Ông-kok), named after Koxinga's hereditary title of "Prince of Yanping" (Chinese: 延平郡王; pinyin: Yánpíng jùnwáng) that bestowed by the Yongli emperor of the South Ming.[4] Taiwan was initially referred to by Koxinga as Tungtu (Chinese: 東都; pinyin: Dōngdū; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tang-to, literally "eastern capital"). In 1664, his son and successor Zheng Jing renamed it as Tungning (Chinese: 東寧; pinyin: Dōngníng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tang-lêng, literally "Eastern Pacification"), the name change imparted a switching intent by Jing to settle in Taiwan permanently instead of an unachievable expectation of being a temporary capital on the east for awaiting the Yongli emperor there, whom had been executed by the Qing forces two years ago.[5][6][7]

In Britain, it was known as Tywan (Taiwan),[8][9][10][11][4] named after the King's residence at the city of "Tywan" in present-day Tainan.[12][13] The period of rule is sometimes referred to as the Koxinga dynasty.[1]

History

Capture of Taiwan and establishment of the Kingdom

Following the defeat of the Ming dynasty in 1644, the Manchu Qing offered several high-ranking Ming officials and military leaders positions in the Qing court in exchange for cessation of resistance activities. Zheng Zhilong, a Ming admiral and father of Koxinga, accepted the Qing offer, but was later arrested and executed for not ceding control of his military forces to the Qing cause when asked to do so. After learning of this whilst pursuing studies overseas, Koxinga pledged to assume his father's position and control of his remaining forces in order to re-establish Ming control of China.[14] With most of China controlled by the Qing, Koxinga discovered the situational strategic advantages provided by a retreat and occupation of Taiwan from the translator Ho-Bin who was working for the Dutch East India Company.[15] Supplied by Ho-Bin with maps of the island, Koxinga marshalled his forces, estimated at 400 ships and 25,000 soldiers, and seized the Pescadores (also known as Penghu Islands) so as to utilize them as a strategic staging point from which to invade Taiwan, at the time a foreign land outside the boundaries of China controlled by the Dutch.[14][16][17][18][19]

In 1661, Koxinga's fleet forced an entry to Lakjemuyse and made landing around Fort Provintia. In less than a year, he captured Fort Provintia and besieged Fort Zeelandia; with no external help coming, Frederick Coyett, the Dutch governor negotiated a treaty,[20] where the Dutch surrendered the fortress and left all the goods and property of the Dutch East India Company behind. In return, most Dutch officials, soldiers and civilians were allowed to leave with their personal belongings and supplies and return to Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia), ending the 38 years of Dutch colonial rule on Taiwan. Koxinga did, however, detain some Dutch "women, children, and priests" as prisoners.[21] He then proceeded on a tour of inspection with a contingent of nearly 100,000 soldiers to "see with his own eyes the extent and condition of his new domain."[22]

Realizing that developing his forces in Taiwan into a large enough threat to unseat the Qing would not be achieved in the short term, Koxinga began transforming Taiwan into a practically proper, albeit preferably temporary, seat of power for the Southern Ming loyalist movement. Replacing the Dutch system of government previously used in Taiwan, Koxinga instituted a Ming-style administration, the first Chinese governance in Taiwan. This system of government was divided into six departments: civil service, revenue, rites, war, punishment, and public works.[14] Great care was taken to symbolise support for the Ming legitimacy, an example being the use of the term guan instead of bu to name departments, since the latter is reserved for central government, whereas Taiwan was to be a regional office of the rightful Ming rule of China.[23] Zheng Jing dutifully complied with the prescribed procedures for Ming officials by regularly presenting reports and paying tribute to the absent Ming emperor.[24] Formosa (Taiwan) was also renamed by Koxinga as Tungtu, though this name was later changed by his son, Zheng Jing, to Tungning.[25]

Development

The most immediate problem Koxinga faced after the successful invasion of Taiwan was a severe shortage of food. It is estimated that prior to Koxinga's invasion the population of Taiwan was no greater than 100,000 people, yet the initial Zheng army with family and retainers that settled in Taiwan is estimated to be 30,000 at minimum.[14] To address the food shortage, Koxinga instituted a tuntian policy in which soldiers served the dual role of farmer when not assigned active duty in a guard battalion. No effort was spared to ensure the successful implementation of this policy to develop Taiwan into a self-sufficient island, and a series of land and taxation policies were established to encourage the expansion and cultivation of fertile lands for increased food production capabilities.[23]

Lands held by the Dutch were immediately reclaimed and ownership distributed amongst Koxinga's trusted staff and relatives to be rented out to peasant farmers, whilst properly developing other farmlands in the south and the claiming, clearing, and cultivating of Aborigine lands to the east was also aggressively pursued.[14] To further encourage expansion into new farmlands, a policy of varying taxation was implemented wherein fertile land newly claimed for the Zheng regime would be taxed at a much lower rate than those reclaimed from the Dutch, considered "official land".[23]

Koxinga, at one point, declared his intention to conquer the Philippines in retaliation for the Spanish mistreatment of the Chinese settlers there.[26] His originally stated intentions for conquering Taiwan from the Dutch also included the desire to protect Chinese settlers in Taiwan from maltreatment by the Dutch.[27]

Following the death of Koxinga in 1662 due to malaria, his son Zheng Jing took over the Zheng regime, leading the remaining 7,000 Ming loyalist troops to Taiwan.[14] Zheng Jing sought to sinicize Taiwan and naturalize Han Chinese customs.[28][29]

Differing from Koxinga, it seems Jing attempted to reconcile peacefully with the Qing by travelling to Peking and bidding for Taiwan to become an autonomous state, but refusing to accept the conditions of compulsory Manchu hairstyle and regular tributes of currency and soldiers. In response to raids by Zheng Jing and in an effort to starve out the forces in Taiwan, the Qing decreed to relocate all of the southern coastal towns and ports that had been the targets of raids by the Zheng fleet and thus provided supplies for the resistance. This to a large extent backfired and from 1662 to 1664 six major waves of immigration occurred from these areas to Taiwan due to the severe hardships incurred from this relocation policy. In a move to take advantage of this Qing misstep, Zheng Jing promoted immigration to Taiwan by promising the opportunity for free eastern land cultivation and ownership for peasants in exchange for compulsory military service by all males in case the island should need to be defended against Qing invaders. About 1,000 previous Ming government officials moved to Taiwan fleeing Qing persecution.[23]

Zheng Jing also recruited his early tutor, Chen Yonghua, and passed to him most official government affairs. This saw the establishment of many important developmental policies for Taiwan in education, agriculture, trade, industry and finance, in addition to a tax system almost as harsh as that of the Dutch colonials.[14]

Taiwan soon saw the establishment of Chinese language schools for both the Chinese and indigenous populations and a concerted effort to break Dutch and Indigenous religious, language, and other cultural influences, and promotion of Chinese socio-cultural hegemony along with further expansion of towns and farmland into the south and east.[23] This was realised in the eventual closure of all European and therefore Christian schools and churches in Taiwan, the opening of Confucian temples and the institution of the Confucian civil service exams to coincide with the implemented Confucian education system. Chen Yong-hua is credited for the introduction of new agricultural techniques, such as water-storage for annual dry periods and the deliberate cultivation of sugar cane as a cash crop for trade with the Europeans, in addition to the cooperative unit machinery for mass refining of sugar. The island became more economically self-sufficient with Chen's introduction of mass salt drying by evaporation, creating much higher quality salt than by rock deposits which were found to be very rare in Taiwan.[23]

The Dutch had previously maintained a monopoly of trade of certain goods with the Aboriginal tribes across Taiwan, and this monopoly of trade was not only maintained under the Zheng regime, but was actively turned into a quota-tribute system of exploitation of the native tribes to aid in international trade.[23]

Trade with the British occurred from 1670 through until the end of the Zheng regime, though for the most part limited because of the Zheng monopoly on sugar cane and deer hide, as well as the inability of the British to match the price of East Asian goods for resale. Throughout its existence, Tungning was subject to the Qing sea ban (haijin), limiting its trade with mainland China to smugglers. Aside from the British, Zheng major trade occurred with the Japanese and Dutch, though evidence of trade with many Asian countries exists.[23]

Zheng Jing's navy defeated a combined Qing-Dutch fleet commanded by Han Banner general Ma Degong in 1664 and Ma was killed in the battle. The Dutch looted relics and killed monks after attacking a Buddhist complex at Putuoshan on the Zhoushan islands in 1665.[30]

Zheng Jing's navy executed thirty four Dutch sailors and drowned eight Dutch sailors after ambushing, looting and sinking the Dutch fluyt ship Cuylenburg in 1672 on northeastern Taiwan. Only twenty one Dutch sailors escaped to Japan. The ship was going from Nagasaki to Batavia on a trade mission.[31]

On a constant war footing, and denied maritime trade by the hostile Dutch-Qing alliance, the Kingdom of Tungning intensively exploited these lands to feed their vast army. This resulted in a number of brutally suppressed rebellions by the indigenous population and a gradual weakening of the competing Kingdom of Middag.[32]

A series of major conflicts between the Kingdom of Tungning and the Saisiyat people left the Saisiyat decimated and with much of their land in the hands of the Kingdom. The details of the conflicts remain mysterious however historians agree that the outcome was negative for the Saisiyat.[33]

Collapse

Following the death of Zheng Jing in 1681, the lack of an official heir meant rule of Taiwan would pass to his illegitimate son. This caused great division in the government and military powers, resulting in an exceptionally destructive struggle for the succession. Seizing the advantage presented by the infighting, the Qing dispatched their navy with Shi Lang at its head, destroying the Zheng fleet led by Liu Guoxuan at the Penghu Islands. In 1683, after the Battle of Penghu, Qing troops landed in Taiwan, Zheng Keshuang gave in to the Qing dynasty's demand for surrender after being convinced by the "surrender" faction led by Feng Xifan and Liu Guoxuan. His kingdom was incorporated into the Qing dynasty as part of Fujian province, ending more than two decades of rule by the Zheng family.[34]

Zheng Keshuang was taken to Beijing, where he was ennobled by the Qing emperor as Duke of Hanjun (漢軍公); together with his family and leading officers, he was also inducted into the Eight Banners. Junior members of the House of Koxinga acquired the hereditary style of Sia (舍).[35] The Qing sent the 17 Ming princes still living on Taiwan back to mainland China where they spent the rest of their lives.[36]

Troops who specialized at fighting with rattan shields and swords, Tengpaiying (藤牌營), were recommended to the Kangxi Emperor. Kangxi was impressed by a demonstration of their techniques and ordered 500 of them to reinforce the siege of Albazin against the Russians, under Ho Yu, a former Koxinga follower, and Lin Hsing-chu, a former General of Wu. Attacking from the water using only the rattan shields and swords, these troops cut down Russian forces traveling by rafts on the river, without suffering a single casualty.[37][38][39][40]

Rulers

| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) | Title(s) | Reign (Lunar calendar) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) 鄭成功 Zhèng Chénggōng (Mandarin) Tēⁿ Sêng-kong (Hokkien) Chhang Sṳ̀n-kûng (Hakka) (1624–1662) |

Prince of Yanping (延平王) Prince Wu of Chao (潮武王) |

14 June 1661 Yongli 15-5-18 | 23 June 1662 Yongli 16-5-8 |

| - |  |

Zheng Xi 鄭襲 Zhèng Xí (Mandarin) Tēⁿ Sip (Hokkien) Chhang Sip (Hakka) (1625–?) |

Protector (護理) | 23 June 1662 Yongli 16-5-8 | November 1662 Yongli 17 |

| 2 |  |

Zheng Jing 鄭經 Zhèng Jīng (Mandarin) Tēⁿ Keng (Hokkien) Chhang Kîn (Hakka) (1642–1681) |

Prince of Yanping (延平王) Prince Wen of Chao (潮文王) |

November 1662 Yongli 17 | 17 March 1681 Yongli 35-1-28 |

| - |  |

Zheng Kezang 鄭克𡒉 Zhèng Kèzāng (Mandarin) Tēⁿ Khek-chong (Hokkien) Chhang Khiet-chong (Hakka) (1662–1681) |

Prince Regent (監國) | 17 March 1681 Yongli 35-1-28 | 19 March 1681 Yongli 35-1-30 |

| 3 |  |

Zheng Keshuang 鄭克塽 Zhèng Kèshuǎng (Mandarin) Tēⁿ Khek-sóng (Hokkien) Chhang Khiet-sóng (Hakka) (1670–1707) |

Prince of Yanping (延平王) Duke Hanjun (漢軍公) |

19 March 1681 Yongli 35-1-30 | 5 September 1683 Yongli 37-8-13 |

Reigning family

| Adoption | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Zhilong | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prince of Yanping | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Chenggong (KOXINGA) | Tagawa Shichizaemon | Zheng Du | Zheng En | Zheng Yin | Zheng Xi | Zheng Mo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Jing | Zheng Cong | Zheng Ming | Zheng Rui | Zheng Zhi | Zheng Kuan | Zheng Yu | Zheng Wen | Zheng Rou | Zheng Fa | Zheng Gang | Zheng Shou | Zheng Wei | Zheng Fu | Zheng Yan | Zheng Zuanwu | Zheng Zuanwei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Niru | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Kezang | Zheng Keshuang | Zheng Kexue | Zheng Kejun | Zheng Keba | Zheng Kemu | Zheng Keqi | Zheng Keqiao | Zheng Ketan | Zheng Kezhang | Zheng Kepei | Zheng Kechong | Zheng Kezhuang | Zheng Bingmo | Zheng Kegui | Zheng Bingcheng | Zheng Bingxun | Zheng Kexi | Zheng Wen | Zheng Bao | Zheng Yu | Zheng Kun | Zheng Ji | Zheng Zhong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Anfu | Zheng Anlu | Zheng Ankang | Zheng Anji | Zheng Andian | Zheng Ande | Zheng Yan | Zheng Yi | Zheng Qi | Zheng Anxi | Zheng Anqing | Zheng Anxiang | Zheng Anguo | Zheng Anrong | Zheng Anhua | Xialing | Bailing | Shunling | Yongling | Changling | Qingling | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Shijun | Zheng Xianji | Zheng Xiansheng | Zheng Fu | Zheng Beng | Zheng Ai | Zheng Xian | Zheng Pin | Zheng Weng | Zheng Ming | Zheng Rui | Zheng Xing | Zheng Sheng | Zheng Jia | Zheng Guan | Zheng Pin | Zheng Qi | Zheng Tu | Zheng Dian | Zheng Lin | Zheng Qi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Bin | Zheng Min | Zheng Chang | Zheng Jin | Zheng Gui | Zheng Song | Zheng Bo | Zheng Ji | Zheng Bangxun | Zheng Bangrui | Zheng Bangning | Zheng Wenkui | Zheng Wenbi | Zheng Wen'ying | Zheng Wenfang | Zheng Wenguang | Zheng Wenzhong | Zheng Wenquan | Zheng Wen'wu | Zheng Wenlian | Zheng Wenmin | Zheng Wenhan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Jizong | Zheng Chengzong | Zheng Cheng'en | Zheng Cheng'yao | Zheng Chenggang | Zheng Chengxu | Liubu | Qinglu | Qingfu | Qing'yu | Qingxiang | Shuangding | Qingpu | Qingmao | Yingpu | Shanpu | Qingxi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruishan | Tushan | Deshan | Rongshan | Deyin | Deyu | Songhai | Deshou | Chang'en | Shi'en | Fu'en | Songtai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yufang | Yuhai | Yuchen | Enrong | Enfu | Enlu | Enhou | Enbao | Enlian | Xingsheng | Yulin | Yucheng | Yushan | Yufu | Yuhai | Yusheng | Yuliang | Runquan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Yi | Zheng Ze | Chongxu | Erkang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zheng Jichang | Shuzeng | Shuyue | Shuwang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

Citations

- "Historical and Legal Aspects of the International Status of Taiwan (Formosa)" by Ng Yuzin Chiautong, published on August 28, 1971, WUFI

- Hang, Xing (2016). "Contradictory Contingencies: The Seventeenth-Century Zheng Family and Contested Cross-Strait Legacies". American Journal of Chinese Studies. American Journal of Chinese Studies 23. 23: 173–182. JSTOR 44289147. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

Despite vast political differences, scholars in mainland China and Taiwan position the two men (Zheng Chenggong and Zheng Jing) along a continuum ranging from loyalists of the ethnically Han Ming dynasty (1368–1662) determined to recover the mainland from the Manchu Qing (1644–1911) to founders of an independent maritime state.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Kerr, George H. (11 April 1945). "Formosa: Island Frontier". Far Eastern Survey. 14 (7): 80–85. doi:10.2307/3023088. JSTOR 3023088.

- Kang, Peter (2016), "Koxinga and his maritime regime in the popular historical writings of post-Cold War Taiwan", in Andrade, Tonio; Hang, Xing (eds.), Sea Rovers, Silver, and Samurai: Maritime East Asia in Global History, 1550–1700, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 335–352, ISBN 978-0-8248-5276-4. pp. 347–348.

- Xing Hang (2010). The Zheng "state" on Taiwan. Between Trade and Legitimacy, Maritime and Continent: The Zheng Organization in Seventeenth-Century East Asia (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. p. 209.

The first major shift in direction was symbolic and seemingly harmless, involving a mere question of names. In 1664, soon after he and his soldiers fled back to Taiwan, Zheng (Jing) changed the official title of the island from Dongdu to Dongning, or “Eastern Pacification.” The move was a subtle statement of the goals he intended to achieve for his organization. Dongdu, coined by his father, implied a new seat of Ming government, of making Taiwan “China,” but still hinted at future efforts at restoration of the Mainland. "Dongning" imparted the additional feeling of settled permanency, of creating a new “China” outside of a corrupted, “barbarianized” one, and involving a long-term commitment to Taiwan, rather than as the focal point of a broader movement. Moreover, the change signaled a desire to end hostilities with the Qing and arrive at some kind of political settlement.

- 《東山國語》Dongshan Guoyu by Zha Jizuo:「會延平王成功薨,長子經嗣立,臺灣初稱東都,改明京以候桂王之蹕。已不克至,乃改東寧國,複築奉天城於對渡以居官。」

- 《清一統志臺灣府》:「本朝順治十八年,海寇鄭成功逐荷蘭夷據之,偽置承天府,名曰東都;設二縣,曰天興、萬年.其子鄭經(按府志,鄭經一名錦)改東都曰東寧省,升二縣為州。」

- "Invitation from the "King of Tywan"". nmth.gov.tw. National Museum of Taiwan History. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - The select committee of the house of Lords (5 June 1829), "Tywan on Formosa", Report relative to the trade with the East Indies and China, The Bavarian State Library, pp. 392–396.

- "The British-Zheng trading agreement". nmth.gov.tw. National Museum of Taiwan History. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Young-tsu Wong (2017), "The Antagonism Across the Taiwan Strait", China's Conquest of Taiwan in the Seventeenth Century: Victory at Full Moon, Springer, p. 116, ISBN 978-9811022487,

On 10 September 1670 the British East India Company and Zheng Jing (the second monarch of the kingdom), whom the Englishmen addressed as "King of Tywan," concluded a trade agreement, which went into effect in the following year. Thereafter, the company sent Simon Delboe to Taiwan as its chief representative and John Dacus as his reputy. The commercial tie lasted until the fall of Taiwan in 1684... Ellis Crisp, who had commanded the first English fleet to visit Taiwan, reported that Zheng Jing had endeavored "to make Tywan [Taiwan] a place of great trade".

- The select committee of the house of Lords (5 June 1829), "Tywan on Formosa", Report relative to the trade with the East Indies and China, The Bavarian State Library, pp. 392–396,

The letter written from the Court to the King of Formosa, dated London, 6th September 1671, "May it please your Majesty, By advice from our agents and Council of Bantam, we understand that, upon your Majesty's Encouragement, they had made a Beginning of Trade in your City of Tywan, and had been kindly received by your Majesty there... To that purpose we have now sent out several ships, with cargoes in part from hence, cloths, stuffs, lead, and other commodities, and have appointed to be ladened at Bantam, calicoes and other Indian goods, severally for sale at your City of Tywan, with orders to take in exchange sugars,skins, and other commodities.

- Kerr, George H. (11 April 1945). "Formosa: Island Frontier". Far Eastern Survey. 14 (7): 81. doi:10.2307/3023088. JSTOR 3023088.

- Lin, A.; Keating, J. (2008). Island in the Stream : A Quick Case Study of Taiwan's Complex History (4th ed.). Taipei: SMC Pub. ISBN 9789576387050. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- Andrade, Tonio (2005). "Chapter 11: The Fall of Dutch Taiwan". How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.

- Xing Hang (2010). "The grand stage of maritime history". Between Trade and Legitimacy, Maritime and Continent: The Zheng Organization in Seventeenth-Century East Asia. University of California, Berkeley: 56.

After becoming an official, Zhilong, too, tacitly acknowledged this separation by permitting junks to trade on the island but forbidding the VOC from coming to Fujian, because “our country’s emperor has issued an edict prohibiting foreigners from entering China. Taiwan thus clearly lay outside the territorial scope of the Ming.

- Xing Hang (2010). "Brave New World". Between Trade and Legitimacy, Maritime and Continent: The Zheng Organization in Seventeenth-Century East Asia. University of California, Berkeley: 167.

In the winter of 1661, as his troops remained deadlocked in front of Fort Zeelandia, Luo Zimu arrived in Taiwan with a letter from Zhang Huangyan (張煌言) urging Zheng (Koxinga) to abandon his fruitless siege and return to the cause of Ming restoration... Zhang accused Zheng of using his soldiers of righteousness as sacrificial lambs on the altar of his personal interests. Due to his selfish decision to seek continued survival and refuge for his own organization on a wild foreign island outside of “China”, they now led a precarious existence of homesickness and deprivation.

- Xing Hang (2010). "Brave New World". Between Trade and Legitimacy, Maritime and Continent: The Zheng Organization in Seventeenth-Century East Asia. University of California, Berkeley: 190.

Zheng (Koxinga) claimed that “my father Iquan [Zhilong] had designated this land out of friendship” to the VOC during a time when its “ships first came to seek trade but did not have the least piece of land in these parts.” However, Chenggong went on to emphasize, both in his letter and a placard issued to all residents of Taiwan, that Zhilong had only “lent [the island] to the Company... The Dutch envoys issued a skillful rebuttal of his narrative by bringing up the formal agreement struck between the VOC and Ming authorities that exchanged Penghu for Taiwan, an occupation that Zheng Zhilong himself had recognized. They concluded from the weight of evidence that Taiwan did not come “under the Empire of China, but belonged to the Company,” and Chenggong had “no rights or pretenses” to this territory.

- Xing Hang (2010). "A question of hairdos and fashion". Between Trade and Legitimacy, Maritime and Continent: The Zheng Organization in Seventeenth-Century East Asia. University of California, Berkeley: 240.

Zheng Jing told the Qing negotiators that he could not abandon Taiwan for the sake of land and ranks on the Mainland. According to his letter:

“Today, I have opened up another universe at Tungning, outside of the domain. Its area is thousands of li, and its grain can last decades. The barbarians from the four directions submit, myriad products circulate, and the living masses gather and receive education. These are enough to be strong on its own. What do I have to desire from a feudatory title (of Qing)? What have I to envy about the Central Land (Zhongtu)?” (今日東寧,版圖之外另闢乾坤,幅員數千里,糧食數十年。四夷效順,百貨流通,生聚教訓,足以自強,又何慕於藩封?何羨於中土哉?) Similarly, he announced to Kong (Kong Yuanzhang, a Qing representative) his creation of an entirely new kingdom abroad: “Today, Tungning is far away overseas, and does not form part of the domain (非屬版圖之中). - "Koxinga-Dutch Treaty (1662)" Appendix 1 to Bullard, Monte R. (unpub.) Strait Talk: Avoiding a Nuclear War Between the U.S. and China over Taiwan. Monterey Institute of International Studies Archived 2007-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Davidson (1903), p. 49.

- Davidson (1903), p. 50.

- Wills, John E., Jr. (2006). "The Seventeenth-century Transformation: Taiwan under the Dutch and the Cheng Regime". In Rubinstein, Murray A. (ed.). Taiwan: A New History. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 84–106. ISBN 9780765614957.

- John Robert Shepherd (1993). Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press. pp. 469–470. ISBN 0804720665.

- Lin & Keating (2008), p. 13.

- Foccardi, Gabriele (1986). The last warrior: the life of Cheng Chʻeng-kung, the lord of the "Terrace Bay" : a study on the Tʻai-wan wai-chih by Chiang Jih-sheng (1704). O. Harrassowitz. p. 97.

- Huang Dianquan (1957). "Yongli 15.3". Haiji jiyao. Taipei: Haidong shufang. pp. 22–49.

- Xing Hang (2010). "The Zheng "state" on Taiwan". Between Trade and Legitimacy, Maritime and Continent: The Zheng Organization in Seventeenth-Century East Asia. University of California, Berkeley: 195.

The sources we have available and some newly discovered records reveal that Zheng Jing proved to be a highly capable leader in his own right who successfully met the challenge of survival on a new frontier and established the foundations for a new state on Taiwan... He tried to naturalize Han customs, especially hair and clothing, to a “foreign” and peripheral island, while relegating physical “China” to abstract historical memory... Taiwan, then, did not merely serve as an economic base to prepare for an inevitable future restoration campaign, but the focus for development and settlement in its own right.

- Young-tsu Wong (2017), "The Antagonism Across the Taiwan Strait", China's Conquest of Taiwan in the Seventeenth Century: Victory at Full Moon, Springer, pp. 114–115, ISBN 978-9811022487.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c. 1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1316453841.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-1316453841.

- Wang, Hsing'an (2009). "Quataong". Encyclopedia of Taiwan.

- Cheung, Han (22 November 2020). "Taiwan in Time: The ceremony that endured the times". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Copper, John F. (2000). Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China) (2nd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780810836655. OL 39088M.

- "Min Hakka Language Archives". Min Hakka Language Archives. Academic Sinica. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Jonathan Manthorpe (15 December 2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan. St. Martin's Press. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-230-61424-6.

- Jonathan D. Spence (1991). The Search for Modern China. Norton. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1.

- R. G. Grant (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK Pub. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Louise Lux (1998). The Unsullied Dynasty & the Kʻang-hsi Emperor. Mark One Printing. p. 270.

- Mark Mancall (1971). Russia and China: their diplomatic relations to 1728. Harvard University Press. p. 338. ISBN 9780674781153.

Sources

- Davidson, James W. (1903). "Chapter IV: The Kingdom of Koxinga: 1662–1683". The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1887893. OL 6931635M.