Jesse Lawson

Jesse Lawson (May 18, 1856 – November 8, 1927) was an African American lawyer, educator, and activist. He received a Master of Arts degree from Howard University School of Law, and served as an officer of the Afro-American Council, where he promoted racial justice and anti-Jim Crow legislation to the public and before Congress. He co-founded Frelinghuysen University with his wife, educator and activist Rosetta Lawson.

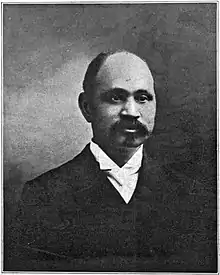

Jesse Lawson | |

|---|---|

Lawson in 1903 | |

| Born | May 18, 1856 |

| Died | November 8, 1927 |

| Education | Howard University (B.A.) Howard University School of Law (B.L.) (M.A.) |

| Occupation | Lawyer, educator, journalist |

| Known for | Political activism, co-founding Frelinghuysen University |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4 |

Family and education

Lawson was born in Nanjemoy, Maryland, on May 18, 1856, to Jesse and Charlotte Lawson.[1] At an early age, after his parents' deaths, he moved to Plainfield, New Jersey, with W. M. McGough, who took over his education.[2]

He attended Howard University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1881, and delivered the first oration at the commencement.[1][3] He went on to attend Howard University School of Law where he earned a Bachelor of Laws in 1884 and a Master of Arts the following year.[1] Later, from 1901 to 1905, he attended special lectures as a member of the American Academy of Political and Social Science at the University of Pennsylvania.[1][4]

Lawson married Rosetta Lawson (née Coakley) in Washington, D.C., in 1884. Together they had a daughter and three sons.[4] They were married until his death in 1927.[1]

Career

In 1882, after earning his B.A. from Howard University, Lawson began working as a legal examiner at the Bureau of Pensions, a position he held for 44 years, until his retirement in May, 1926.[1][2] During this time, he served as the editor of The Colored American, an African American newspaper in Washington, D.C., from 1895 until 1897.[1][5] Later, in 1889, he served as the counsel for John Mercer Langston before the United States House of Representatives, after Langston contested his loss in the 1888 United States House of Representatives elections. The challenge was eventually successful, and on September 30, 1890, Lanston assumed the House seat.[4][5][6]

Lawson's career in academics began in the Lyceum of the Second Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. where he lectured in sociology, and he became president and professor of sociology and ethics at the Bible College and Institute for Civic and Social Betterment in 1906.[1] He also gave lectures on sociology at other institutions in Washington, D.C.[5]

Lawson and his wife organized a branch of the Bible Educational Association in 1906, with Kelly Miller elected as its president. Lawson was later instrumental in the founding of the Inter-Denominational Bible College, where he was named as president. In 1917, the Bible Educational Association and the Inter-Denominational Bible College merged, forming Frelinghuysen University, with Lawson as its head.[1][7] The university was focused towards working Black adults, allowing them to further their education when unable to meet the requirements of traditional schooling. The university charged minimal tuition and classes were often taught out of homes in the area. The first classes were taught in Lawson's home.[1][7][8] Lawson remained president of the university for 21 years.[2]

Activism and politics

Lawson was a member of the Republican Party, and was a delegate to the 1884 Republican National Convention.[1]

He was an officer of the Afro-American Council (AAC), as well as a representative of its legal bureau.[9][10][5] In this capacity, he worked with Daniel Alexander Payne Murray in defining a strategy of drawing attention to the social, political, and economic issues African Americans faced, with the goal of getting congress to consider the effects of disenfranchisement on African Americans. This led, in 1902, to the House Committee on Labor writing a bill to create the Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission. The commission would be tasked with, "a comprehensive investigation of the condition" of African Americans in the United States, as well as "best means of promoting harmony between the races". The bill was sponsored by Republican congressman Harvey S. Irwin, and Lawson, with Murray, testified before Congress in support of the bill. The bill was never passed to law.[5] Lawson would go on to, in his capacity with the AAC, support other racial justice and anti-Jim Crow legislation and try to focus the attention of congress on disenfranchisement.[5]

In the early 1900s, he founded the National Sociological Society, and served as its vice president.[1][11] The society was established with the goal of considering, "the race problem", and gathering information on race relations to present to the public and Congress.[5] Its membership was open to "any person of good character" and charged a fee or assessment of dues. A partial list of the membership names at least 164 members, both African American and white, and from the northern and southern states.[1] The society convened a single conference in 1903, in response to Booker T. Washington's call for a national conference on race relations.[1] The conference, which brought together African Americans and whites, resulted in substantive discourse. After the conference Lawson edited and published a volume documenting the event.[1][5] Law professor Susan Carle described the opinions discussed at the conference as "inchoate and disparate, pointing to the still substantially unsettled status of strategic choices for a racial justice campaign for the new century". The participants, however, did widely agree that "[a]s solutions of the race problem we regard colonization, expatriation and segregation as unworthy of future consideration", and "[we] have abiding faith in the principles of human rights established in the Declaration of Independence and the national Constitution".[1][5]

In 1895, he was the president of the board of commissioners of the District of Columbia for the Cotton States and International Exposition, overseeing the creation of exhibits to demonstrate the skill and advancement of African Americans since emancipation.[12] He served as the vice president of the National Emancipation Commemorative Society. Created in 1909, the society organized celebrations in honor of the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation.[1][13]

He was active in support of the temperance movement,[14] and gave public talks on the importance of enfranchisement, education, and the moral and social development of the African American community.[15][16][17] He also authored several works on political causes, including How to Solve the Race Problem, The Ethics of the Labor Problem, and The Vacant Chair in Our Educational System.[1][4]

Death

Lawson died on November 8, 1927, at Freedmen's Hospital, and was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Washington, D.C.[2][7][18] Michael R. Hill wrote in Diverse Histories of American Sociology that he and his wife "dedicated their lives to race betterment."[1]

References

- Hill, Michael R. (2005). Diverse histories of American sociology. Leiden: Brill. pp. 130–133. ISBN 978-90-04-14363-0. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- "Jesse Lawson is Dead; Served U.S. 44 Years". Evening Star. November 6, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "Howard University, Commencement of the Collegiate Department, Seven Bachelors of Arts". National Republican. June 3, 1881. p. 4. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Mather, Frank Lincoln (1915). Who's who of the colored race: a general biographical dictionary of men and women of African descent ; vol. 1. s.n. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Carle, Susan D. (October 31, 2013). "The Afro-American Council's Legal Work, 1898–1908". Defining the Struggle: National Racial Justice Organizing, 1880-1915. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199945740.003.0007. ISBN 9780199945740.

- "LANGSTON, John Mercer | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Carney, Jessie (2003). Notable Black American Women. Detroit: Gale Research. pp. 399–40. ISBN 978-0810391772.

- Cooper, Anna J. (n.d.). "Letter to Mordecai Johnson". Decennial Catalogue of Frelinghuysen University. pp. 67–69. Archived from the original on December 27, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- Adams, Cyrus Field (1902). National Afro-American Council - A HISTORY OF THE ORGANIZATION, ITS OBJECTS, SYNOPSES OF PROCEEDINGS, CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS, PLAN OF ORGANIZATION, ANNUAL TOPICS, ETC (PDF). Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "The National Afro-American Council". The Appeal. July 7, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "Race Segregation - Theme of Paper Read Before Sociological Society". Evening Star. November 10, 1903. p. 7. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "District Exhibit". Evening Star. August 13, 1895. p. 3. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "Clipped From The Uniontown News". The Uniontown News. October 15, 1915. p. 7. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "Program of Nineteenth Street Baptist Church WCTU". Evening Star. June 23, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "The Light of History - Prof. Jesse Lawson's Review of Thirty Years". The Colored American. February 8, 1902. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "Negro Young People's Christian and Educational Congress". Evening Star. July 17, 1906. p. 12. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "Colored People's Need - Prof. Lawson Favors Moral and Social Development". Evening Star. May 24, 1909. p. 18. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Fitzpatrick, Sandra; Goodwin, Maria R. (2001). The Guide to Black Washington: Places and Events of Historical and Cultural Significance in the Nation's Capital. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0781808715.