History of Berliner FC Dynamo (1978–1989)

The history of Berliner FC Dynamo (1978–1989) comprises the events associated with Berliner FC Dynamo from 1978 to 1989.

First league title (1978–1979)

BFC Dynamo was qualified for the 1978–79 UEFA Cup. The team was drawn against Yugoslav powerhouse Red Star Belgrade in the first round. The team won the first leg 5–2 at home in front of 26,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark.[1][2] Hans-Jürgen Riediger scored the first three goals for BFC Dynamo in the match.[3] But the team lost the return leg 4–1 on stoppage time and was eliminated on goal difference.[4] The 1978-79 DDR-Oberliga marked a change in East German football. BFC Dynamo opened the season with ten consecutive wins and finally captured its first league title in 1979. The title was secured after a 3–1 win against Dynamo Dresden in the 24th match day in front of 22,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark.[5] The team had managed an astounding 21 wins, four draws and only one loss. Hans-Jürgen Riediger became second placed league top goal scorer with 20 goals.

During a shopping tour in the city of Gießen in Hesse after a friendly match against 1. FC Kaiserslautern on 20 March 1979, midfielder Lutz Eigendorf broke away from the rest of the team and defected to West Germany.[6][7] Lutz Eigendorf was one of the most promising players in East German football.[8] He was a product of the elite Children and Youth Sports School (KJS) "Werner Seelenbinder" in East Berlin and had come through the youth academy of BFC Dynamo.[7][9] He was often called "The Beckenbauer of East Germany", and was considered the figurehead and great hope of East German football.[10] Eigendorf was nicknamed "Iron Foot" by the supporters of BFC Dynamo and was said to be one of the favorite players of Mielke.[11][10] His defection was a slap in the face of the East German regime and allegedly taken personally by Mielke.[10][8][12] Owing to his talent and careful upbringing at BFC Dynamo, it was considered a personal defeat of Mielke.[9] Afterwards, his name would disappear from all statistics and annals of East German football.[11] All fan merchandise with the name or image of Eigendorf were also removed from the market.[8] Eigendorf would die in mysterious circumstances in Braunschweig in 1983.[7][13]

European Cup play and defection (1979-1983)

Winning the league title in the 1978–79 season, BFC Dynamo qualified for its first appearance in the European Cup. BFC Dynamo eliminated Ruch Chorzów and Servette FC in the first two rounds of the 1979-80 European Cup. The team reached the quarter finals, where it faced Nottingham Forest led by Brian Clough. BFC won the first leg 1–0 away, with a single goal scored by Hans-Jürgen Riediger, but was eliminated on aggregate goals, after a 1–3 loss in front ot 30,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Sportpark.[14] Nottingham Forest would later go on and become champions. The win against Nottingham Forest away, made BFC Dynamo the first German team to defeat an English team in England in the European Cup.[15]

The success continued and BFC Dynamo won the league also in the following seasons. BFC Dynamo played a friendly match against VfB Stuttgart during the winter break of the 1981–82 season. The match ended 0–0 in front of 25,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark.[16][17] BFC Dynamo was set for a prestigious encounter with the West German champions Hamburger SV in the first round of the 1982-83 European Cup. The first leg was to be played at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark and many fans were looking forward towards the match. But fearing riots, political demonstrations and spectators expressing sympathies for West German football stars such as Felix Magath, the Stasi imposed restrictions on ticket sales. Only 2,000 tickets were allowed for carefully selected fans. Most seats were instead allocated to Stasi employees, Volkspolizei officers and SED functionaries.[18][19][20] BFC Dynamo managed a draw, but was eliminated after a 0–2 loss in Hamburg. A new friendly match against Stuttgart was then arranged in the 1982–83 season. The match was played in West Germany this time. The match ended 4–3 for Stuttgart in front of 8,000 spectators at the Neckarstadion on 8 March 1983.[17]

The players of BFC Dynamo had political training and were held under a strict discipline, demanding both political reliability, obedience and a moral lifestyle. No contacts with the West was allowed.[21][22][23] The players were also under surveillance by the Stasi. They would have their telephones tapped, their rooms at their training camp tapped and be accompanied by personnel from the Stasi during international trips.[24] The Ministry of the Interior and the Stasi had employees integrated in the club and it is likely that some individual players were recruited as informants, so called Unofficial collaborators (IM), with the task of collecting information about other players.[25][24] During an away trip to Belgrade for a match against Partizan Belgrade in the second round of the 1983-84 European Cup, players Falko Götz and Dirk Schlegel defected to West Germany. With help from the West German Consulate general in Zagreb, they received false passports and managed to escape to Munich.[26][27][28][29] East German state news agency ADN reported that Falko Götz and Dirk Schlegen had been "wooed by West German managers with large sums of money" and "betrayed their team".[28] Although Falko Götz and Dirk Schlegen were labeled as "sports traitors", their defection had little effect on the team. According to Christian Backs, the team only received more political training, and there were no reprisals.[21] However, the loss of two regular players before the match against Partizan Belgrade was a challenge. Coach Bogs decided to give then 18-year old Andreas Thom a chance to make his international debut, in replacement of Falko Götz. Thom would make a terrific debut.[28][27] BFC Dynamo won the match 2–0 and would eventually advance to the quarter finals.

BFC Dynamo faced Italian champions AS Roma in the quarter finals of the 1983–84 European Cup. Thom would be selected to the starting eleven in both legs. BFC Dynamo lost the first match 3–0 away at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome. The team came back and won the return leg 2–1 in front of 25,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark. Thom and Rainer Ernst scored one goal each.[30] However, BFC Dynamo lost the round on aggregate goals and was eliminated.

Dominance in the league (1983–1985)

BFC Dynamo had a run of 36 league matches without defeat in 1982–1984, including the entire 1982–83 season. The team recorded several large victories such as 4–0 home against Magdeburg on 8 May 1982, 0–4 away against F.C. Hansa Rostock on 25 August 1982, 4–0 home against HFC Chemie on 16 April 1983 and 2–9 away against BSG Chemie Böhlen on 7 May 1983. Only after one and a half years of dominance did FC Karl-Marx-Stadt manage to defeat the team in the seventh match day of the 1983–84 season. The last defeat had occurred against SG Dynamo Dresden in the 22nd match day of the 1981–82 season. Rainer Ernst became league top goalscorer in the 1983–84 and 1984-85 DDR-Oberliga seasons. BFC Dynamo managed to score 90 goals in total during the 1984–85 season, which stands as a record for the Oberliga.

Controversy (1985–1986)

BFC Dynamo had the best material conditions in the league and the best team by far.[31] But there had been controversial refereeing decisions in favor of BFC Dynamo in the league, which gave rise to speculations that the dominance of BFC Dynamo was not solely due to athletic performance, but also due to manipulation.[32] Allegations of referee bias was nothing new in East German football and was not isolated to matches involving BFC Dynamo. Alleged referee bias as a source of unrest was a thread that ran from the very first matches of the Oberliga. Alleged referee bias had caused unrest already during the first season of the DDR-Oberliga, when ZSG Horch Zwickau defeated SG Dresden-Friedrichstadt 5–1 in a match which decided the title in the 1949–50 DDR-Oberliga. Another example occurred in 1960 when ASK Vorwärts Berlin defeated SC Chemie Halle away in Halle.[33][34][35] The player bus of ASK Vorwärts Berlin was attacked and the Volkspolizei had to protect the players.[35] The home ground of Union Berlin was closed for two match days as a result of crowd trouble over the performance of referee Günther Habermann during a match between Union Berlin and FC Vorwärts Frankfurt in 1982. The police had been forced to come to the rescue of referee Günther Habermann.[36] German sports historian Hanns Leske claims that referees throughout the history of East German football had a preference for the teams sponsored by the armed and security organs.[35]

BFC Dynamo and its predecessor, Dynamo Berlin, was deeply unpopular in Dresden since the relocation of Dynamo Dresden in 1954.[37] And the club came to be widely disliked and even hated around the country for its privileges, and for being a representative of the capital and the Stasi. Because of this, BFC Dynamo was viewed with more suspicion than affection.[38][32] The sense that BFC Dynamo benefited from soft refereeing decisions did not, as popularly believed, arise first after 1978. It had already existed for years, as shown by the riots among fans of SG Dynamo Schwerin during a match between the two teams in 1968. The disapproval was kept in check as long as the club was relatively unsuccessful, but complaints increased and feelings became inflamed as the club grew successful.[39][40] A turning point was the fractious encounter between BFC Dynamo and Dynamo Dresden at the Dynamo-Stadion in Dresden on 2 December 1978. The match was marked by crowd trouble, with 35 to 38 fans of both teams arrested. The match ended in a 1–1 draw after an equalizer by BFC Dynamo and then SED First Secretary in Bezirk Dresden Hans Modrow blamed the unrest on "inept officiating".[39][41][37] Inexperienced linesman Günter Supp should allegedly have missed an offside position on Hans-Jürgen Riediger in the situation leading up to the equalizer.[42][43] Fans of Dynamo Dresden complained: "We are cheated everywhere, even on the sports field".[36]

The privileges of BFC Dynamo and its overbearing success in the 1980s made fans of opposing teams easily aroused as to what they saw as manipulation by bent referees, especially in Saxon cities such as Dresden and Leipzig.[39] Petitions to authorities were written by citizens, fans of other teams and local members of the SED, claiming referee bias and outright match fixing in favor of BFC Dynamo.[39][44] Animosity towards the club had been growing since its first league titles.[45][46] The team was met at away matches with aggression and shouts such as "Bent champions!" or "Stasi swine!".[37][46] Fans of BFC Dynamo would even be taunted by fans of opposing teams with "Jews Berlin!".[45][47][11] Coach Jürgen Bogs has claimed that the hatred of opposing fans actually made the team even stronger.[48]

Complaints due to alleged referee bias accumulated.[31] High-ranking officials such as Egon Krenz and Rudolf Hellmann even felt compelled to answer petitions in person.[49] SED Functionary Karl Zimmermann from Leipzig had been appointed new general secretary of the German Football Association of the GDR (DFV) in 1983.[35] He was also vice president of the DTSB and enjoyed expanded powers compared to his predecessor Werner Lempert.[50] Zimmermann had been chosen to carry out reforms.[35] The scandal surrounding alleged referee bias in East German football had so undermined the credibility of the national competitions by the mid-1980s that Krenz, Hellman and the DFV under Zimmerman would eventually be forced to impose penalties on referees for poor performance and restructure the referee commission.[39]

The DFV under Karl Zimmermann commissioned a secret review on referee performance and behavior in relation to the matches involving BFC Dynamo, Dynamo Dresden and Lokomotive Leipzig in the 1984–85 season.[31][51][52][nb 1] The review came to the conclusion that BFC Dynamo was favored. It suggested that BFC Dynamo had gained at least 8 points due to clear referee errors during the 26 matches of the season.[53][54][55][56] The review found a direct advantage of BFC Dynamo in ten league and cup matches as well as a disadvantage of its two closest competitors, Dynamo Dresden and Lokomotive Leipzig, in eight matches together.[35][31] It showed that 45 yellow cards had been handed out to Dynamo Dresden and 36 to Lokomotive Leipzig, compared to 16 yellow cards for BFC Dynamo. Yellow cards had also been handed out to key players in Dynamo Dresden and Lokomotive Leipzig prior matches against BFC Dynamo, so that they were banned from the next match.[57][58][31] The review found six referees that were suspected of having favored BFC Dynamo, including Adolf Prokop, Klaus-Dieter Stenzel and Reinhard Purz. It also found referees that were suspected of having disadvantaged Dynamo Dresden and Lokomotive Leipzig, including Klaus-Dieter Stenzel, Wolfgang Henning and Klaus Scheurell.[52] The paper spoke of "targeted influence from other bodies".[53][54][55]

Zimmerman was ultimately worried about the reputation of BFC Dynamo. He warned that the hatred against BFC Dynamo was growing and that the team's performance was being "discredited".[52] He called for a suspension of referee Prokop for two international matches and recommended that several referees, including Prokop, Stenzel and Gehard Demme, should no longer be used in matches involving BFC Dynamo, Dynamo Dresden and Lokomotive Leipzig. Zimmerman later also spoke out against the head of the referee commission Heinz Einbeck, who was a native of Berlin and a sponsoring member of BFC Dynamo.[52][49] The paper ended end up with Egon Krenz, who was a member of the SED Politbüro and the Secretary for Security, Youth and Sport in the SED Central Committee.[52] Several referees would come to receive sanctions for their performance in the following months. The DFV conducted as special review of the final between BFC Dynamo and Dynamo Dresden in the 1984–85 FDGB-Pokal on 8 June 1985.[54] The review found that referee Manfred Roßner and his two assistants had committed an above-average number of errors during the final. The majority of the errors had favored BFC Dynamo.[59] The SED now demanded further actions.[49] The DFV sanctioned referee Roßner with a one-year ban on matches above second tier as well as international matches. Assistant Klaus Scheurell was in turn de-selected from the first round of the next European cup.[49][60][54][59] However, nothing had emerged that indicated that Roßner had been bought by the Stasi. On the countrary, Roßner had been approached by the incensed DFV Vice President Franz Rydz after the match, who took him to task for his performance with the words "You can't always go by the book, but have to officiate in a way that placates the Dresden public".[49] Other officials that were sanctioned by the DFV in the following months were referee Purz and linesman Günter Supp. Purz and Sepp were questioned for their performance during a controversial match between BFC Dynamo and FC Rot-Weiß Erfurt on 26 October 1985 .[61] Purz had allegedly given BFC Dynamo an irregular goal and denied Rot-Weiß Erfurt a clear penalty. BFC Dynamo had won the match 2–3. Also BFC Dynamo coach Jürgen Bogs said after the match that his team did not need such "nature protection".[52] Purz received a suspension for the rest of 1985 and Supp received a suspension for three match days for their performance during the match.[52][54]

The general disillusionment about BFC Dynamo stood at its peak during the 1985–86 season.[62] The DFV hade come under intense pressure to take action against referees that allegedly favored BFC Dynamo, notably from the Department for Sports of the SED Central Committee under Rudolf Hellmann.[63] One of the most controversial situations occurred during a match between Lokomotive Leipzig and BFC Dynamo on 22 March 1986. Lokomotive Leipzig led the match 1-0 into extra time, when BFC Dynamo was awarded a penalty by referee Bernd Stumpf in the 94th minute. Frank Pastor converted the penalty and equalized. The episode, which was later known as "The shameful penalty of Leipzig", caused a wave of protests.[51][32] The DFV presidium and its General Secretary Zimmermann seized the opportunity to take action. Stumpf received a lifetime ban from refereeing. Two SV Dynamo representatives in the referee commission, Einbeck and Gerhard Kunze, were also replaced. The sanctions against Bernd Stumpf were approved by Egon Krenz and Erich Honecker in the SED Central Committee.[64][31][51][35] However, Stumpf managed to send a new video recording of the match to Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) in 2000. The video recording had originally been filmed by BFC Dynamo for training purposes and showed the situation from a different angle. The video recording showed that the decision by Stumpf was correct and that the sanctions against him were unjustified.[65][11]

It was later known that Prokop had been a Stasi officer, employed as an officer in special service (OibE), and that several referees, including Stumpf, had been Stasi informants.[54][66][67][39] But there is no proof that referees stood under direct instructions from the Stasi and no document has been found in the archives that gave the Stasi a mandate to bribe referees.[67][68][69][41] The benefit of controlling important matches in Western Europe, gift to wives and other forms of patronage, might have put indirect pressure on referees to take preventative action, in so called preemptive obedience.[69][68][38][70][71] In order to pursue an international career, a referee would need a travel permit, confirmed by the Stasi.[35][52][72] The German Football Association (DFB) has concluded that "it emerged after the political transition that Dynamo, as the favorite club of Stasi chief Erich Mielke, received many benefits and in case of doubt, mild pressure was applied in its favor".[73] Prokop protests against having manipulated matches.[52] He was never banned from refereeing.[74] He points out that top teams are viewed with skepticism and claims to have never received threatening letters from angry fans.[52] Prokop was still invited to nostalgia matches for the East German national football team in the 2010s.[52]

"I can imagine there was referee manipulation due to the immense pressure from the government and Ministry for State Security. That could have made some referees nervous and influenced their decisions. But we were the strongest team at the time. We didn't need their help."

The picture that the success of BFC Dynamo relied upon referee bias has been challenged by ex-coach Bogs, ex-goalkeeper Bodo Rudwaleit, ex-forward Thom and others associated with the club. Some of them admit that there might have been cases of referee bias. But they insist that it was the thoroughness of their youth work and the quality of their play that earned them their titles.[59][32][76][77] Jürgen Bogs said in an interview with Frankfurter Rundschau: "You cannot postpone 26 matches in one season in the DDR-Oberliga. At that time we had the best football team."[78] Bogs cites a team with strong footballers and modern training methods as the main reasons for the winning streak. The club performed things such as heart rate and lactate measurements during training, which only came to the Bundesliga many years later.[79] Jörn Lenz said in an interview with CNN: "Maybe we had a small bonus in the back of referees' minds, in terms of them taking decisions in a more relaxed way in some situations than if they'd been somewhere else, but one can't say it was all manipulated. You can't manipulate 10 league titles. We had the best team in terms of skill, fitness and mentality. We had exceptional players".[75] Also former referee Bernd Heynemann, who has testified that he was once greeted in person by Mielke in the locker room at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Stadion, said in an interview with the Leipziger Volkszeitung in 2017: "The BFC is not ten times champions because the referees only whistled for Dynamo. They were already strong as a bear".[80][81][82]

Although speculations on manipulation in favor of BFC Dynamo could never be eliminated, it is a fact that BFC Dynamo achieved its sporting success much on the basis of its successful youth work.[83][41][84][85][86] Its youth work during the East German era is still recognized today.[86] The club was able to filter the best talent through nationwide screening and train them in its youth academy.[87] Its top performers of the 1980s came mainly through its own youth teams, such as Thom, Frank Rohde, Rainer Ernst, Bernd Schulz, Christian Backs, Bodo Rudwaleit and Artur Ullrich. These players would influence the team for years. BFC Dynamo recruited fewer established players from the other teams in the Oberliga than what other clubs did, such as Dynamo Dresden and FC Carl Zeiss Jena.[88] Only a fifth of the players who won the ten championships with BFC Dynamo were older than 18 years when they joined the club and those players came from teams that had been relegated from the DDR-Oberliga or the DDR-Liga.[89] The only major transfers to BFC Dynamo from other clubs during its most successful period in the 1980s, were Frank Pastor from then relegated HFC Chemie in 1984 and Thomas Doll from then relegated FC Hansa Rostock in 1986.[90][91][92] These transfers would often be labeled delegations by fans of other teams, but Doll left Hansa Rostock to ensure a chance to play for the national team, and had the opportunity to choose between BFC Dynamo and Dynamo Dresden, but wanted to go to Berlin to be able to stay close to his family and because he already knew players in BFC Dynamo from the national youth teams.[93]

Last titles (1986–1988)

BFC Dynamo was eliminated in the first round of the 1987-88 European Cup after a double loss against FC Girondins de Bordeaux. Defender Norbert Trieloff was transferred to Union Berlin in November 1987. BFC Dynamo won its tenth league title in a row in the 1987–88 season. The league title was narrowly won on goal difference, ahead of runners-up 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig. The team also reached the final of the 1987–88 FDGB-Pokal and defeated Carl Zeiss Jena 2–0 in front of 40,000 spectators at the Stadion der Weltjugend on 4 June 1988. BFC Dynamo secured its first double and won its first cup title since Dynamo Berlin captured the title in 1959. The duo of Thom and Doll, paired with sweeper Rohde, were one of the most effective goal scorers in the late 1980s of East German football. Thom became league top goalscorer during the 1987–88 season and received the East German Footballer of the Year award in 1988.

The long-time club president Kirste was replaced as club president by Herbert Krafft before the 1988–89 season. Kirste had served as president since the club's founding.[94] The club was drawn against West German champions Werder Bremen in the first round of 1988–89 European Cup. BFC Dynamo surprisingly won the first leg 3–0 home in front of 21, 000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark in the first leg. But the team was eliminated after an equally surprising 5–0 defeat in Bremen in the return leg. The return leg would be known in West Germany as the "Second miracle at the Weser".

It has been rumoured that doping might explain the surprising results in the meeting. Researcher Giselher Spitzer claims that players of BFC Dynamo had been given amphetamines before the first leg.[95][84] The Stasi allegedly did not want to take this risk in the return leg in Bremen for fear of controls.[84] However, a more likely explanation for the surprising loss in Bremen is that the players of BFC Dynamo could not cope with the tremendous media pressure following their home win.[95] Roles had changed during the five weeks long break before the return leg. BFC Dynamo was pushed into the role of favorites, while Werder Bremen was given enough time to build motivation.[24][96] The match had high political significance: Mielke had made it clear to the team before the return leg that "this was about beating the class enemy".[97] Players of BFC Dynamo had also been distracted from their match-day preparations by shopping opportunities.[95]

Bogs wanted to travel to Bremen two days in advance. This was denied by the Stasi and the player bus was only allowed to leave East Berlin on Monday morning.[96][97] The player bus then got stuck in West German morning traffic.[97][96] Instead of arriving at around 12:00 PM, the bus arrived at 3:00 PM in Bremen. The schedule of Bogs could no longer be held, so the planned shopping tour was cancelled.[96][97] Werder Bremen manager Willi Lemke stopped by the hotel and instead offered a shopping tour for the next day, where players of BFC Dynamo were given the opportunity to buy West German consumer goods at a "Werder discount".[96][98][99][100][101][102] Some sources suggest that he actually organized a sale at the player hotel were all kinds of goods were sold.[95][97] According to Bogs, the player bus was completely stocked up with home appliances, televisions and consumer electronics when it arrived at the Weser-Stadion 90 minutes before kick-off.[96][97] There are allegations that this was purposely done by Lemke for players of BFC Dynamo to lose their concentration.[98][101] Bogs was forced to justify himself to the DFV the day after the defeat and would receive a reprimand. BFC Dynamo won the next match 5–1 against FC Karl-Marx-Stadt.[96] Bogs has described the defeat in Bremen as the most spectacular defeat in his career, but not his most bitter. He claims that his most bitter defeat was the 4–1 defeat to Red Star Belgrade on stoppage time in the first round of the 1978–79 UEFA Cup.[4]

Decline (1988–1989)

Average home attendance fell from 15,000 to 9,000 during the 1980s.[31] Many fans grew disillusioned by the alleged Stasi involvement. Notably aggravating were the restrictions on tickets sales imposed by the Stasi at international matches, were only a small number of tickets were allowed for ordinary fans, with the vast majority instead allocated to a politically handpicked audience.[103] BFC Dynamo saw the emergence of a well organized hooligan scene during the 1980s, which came to be increasingly associated with skinheads and far-right tendencies in the middle of the 1980s.[45][32][11]

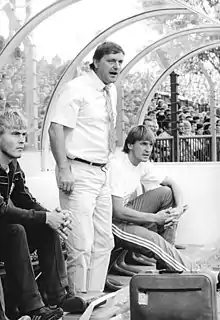

The performance of the team declined during the 1988-89 DDR-Oberliga season. The Central Auditing Commission of the Central Management Office (German: Büro der Zentralen Leitung) (BdZL) of SV Dynamo was authorised by Mielke to investigate the club. The Central Management Office had been aggrieved that the special position of the club had enabled it to escape its control. The commission now used the inquiry as an opportunity to cut the overmighty organization down to size.[104] The commission was critical of inefficient use of resources, materialism, low motivation and lack of political-ideological education of players. As a solution, the Central Management Office assumed full responsibility over the material, political and financial management of the club in mid-1989.[104] Bogs was removed as coach at the end of the 1988–89 season and replaced by Helmut Jäschke.[104][105] Jäschke had previously served as coach of the reserve team. Bogs would later take on the role as "head coach" (German: Cheftrainer) in the club, which was a sort of manager role.[105] Former player Michael Noack would later complain that the BFC Dynamo had suffered from a triple management: the DFV, the Central Management Office of SV Dynamo and the Stasi, whereby a minority had ruled over the club.[106]

BFC Dynamo finished the 1988–89 DDR Oberliga as runners-up behind Dynamo Dresden. The team reached the final of the 1988-89 FDGB-Pokal, after eliminating Union Berlin in the quarter-finals and FC Rot-Weiß Erfurt in the semi-finals. The team defeated FC Karl-Marx-Stadt 1–0 in front of 35,000 spectators at the Stadion der Weltjugend and secured its third cup title. As cup winners, BFC Dynamo was set to play the DFV-Supercup against league champions Dynamo Dresden. The DFV-Supercup was played on 5 August 1989 at the Stadion der Freundschaft in Cottbus. BFC Dynamo defeated Dynamo Dresden 4–1, with two goals scored by Doll, and won the title.

See also

Explanatory notes

References

- "Spielinfo, BFC Dynamo - Roter Stern Belgrade 5:2, 1. Runde-Cup UEFA-Cup 1978/79". Kicker (in German). Nuremberg: Olympia Verlag GmbH. n.d. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- Binkowski, Manfred (19 September 1978). "BFC schwang sich zu großer Form aus" (PDF). Neue Fußballwoche (FuWo) (De) (in German). Vol. 1978, no. 38. Berlin: DFV der DDR. p. 10. ISSN 0323-8407. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- "BFC Dynamo - FK Rotern Stern Belgrade, 5:2, UEFA-Pokal, 1978/1979, 1. Runde". dfb.de (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Fußball-Bund e.V. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- Zwahr, Stefan (11 October 2018). "Albtraum an der Weser: "Unvergessen"". Märkische Oderzeitung (in German). Frankfurt an der Oder: Märkisches Medienhaus GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- "GDR » Oberliga 1978/1979 » 24. Round » BFC Dynamo – Dynamo Dresden 3:1". worldfootball.net (in German). Münster: HEIM:SPIEL Medien GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Der Mann, der den 'Ballack der DDR' ausforschte". Gießener Allgemeine. Gießen: Mittelhessische Druck- und Verlagshaus GmbH & Co. KG. 12 March 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Es bleibt ein Rätsel – wieso starb Ex-FCK Profi Lutz Eigendorf?". srw.de (in German). Stuttgart: Südwestrundfunk. 4 November 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Amshove, Ralf (7 March 2018). "Der rätselhafte Tod des "Beckenbauer des Ostens"". sport.de (in German). Munster: HEIM:SPIEL Medien GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Gareth, Joswig (7 March 2018). "'Eventuell vergiftet'". 11 Freunde (in German). Berlin: 11FREUNDE Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Willmann, Frank (18 June 2014). ""Die Mauer muss weg!"". bpb.de (in German). Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Lutz Eigendorf: Tod eines "Republikflüchtlings"". ndr.de (in German). Hamburg: Norddeutscher Rundfunk. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Weber, Joscha (15 July 2013). "Bundesliga murder mystery, the death of Lutz Eigendorf". dw.com. Bonn: Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "BFC Dynamo – Nottinghamn Forest, 3:1, Europapokal der Landesmeister, 1979/1980, Viertelfinale". dfb.de (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Fußball-Bund e.V. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "15. Januar 1966 – "Stasi-Klub" BFC Dynamo gegründet". wdr.de (in German). Cologne: Westdeutscher Rundfunk. 15 January 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- Schlegel, Klaus (22 December 1981). "Im Schlußspurt vergab der BFC möglichen Sieg" (PDF). Neue Fußballwoche (FuWo) (De) (in German). Vol. 1981, no. 51. Berlin: DFV der DDR. p. 12.

- Braun, Jutta; Wiese, René (3 August 2013). "Die Bombe platzte vorzeitig". 11 Freunde (in German). Berlin: 11FREUNDE Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Ludwig, Udo (18 September 2000). "Betriebsausflug ins Stadion". Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg: SPIEGEL-Verlag Rudolf Augstein GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Braun, Jutta (2015). Münkel, Daniela (ed.). State Security: A reader on the GDR secret police (PDF). Berlin: Stasi Records Agency. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-3-942130-97-4. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Wojtaszyn, Dariusz (5 August 2018). "Der Fußballfan in der DDR – zwischen staatlicher Regulierung und gesellschaftlichem Widerstand". bpb.de (in German). Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Thomas, Frank (8 June 2012). ""Mielkes Spielzeug": Neue Dokumente zu Stasi-Verquickungen des BFC". Leipziger Volkszeitung (in German). Leipzig: Leipziger Verlags- und Druckereigesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Mett (11 June 2014). "Der stasi-Klub: Hinter den Kulissen von Dynamo Berlin". Schweriner Volkszeitung (in German). Schwerin: Zeitungsverlag Schwerin GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ""Fußball für die Stasi": BStU blickt in die Geschichte des BFC Dynamo". Leipziger Volkszeitung (in German). Leipzig: Leipziger Verlags- und Druckereigesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. 16 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Raack, Alex (9 November 2014). "Frank Rohde über seine Karriere zwischen Mielke und Mauer: "Jetzt kannste dir einen brennen!"". 11 Freunde (in German). Berlin: 11FREUNDE Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Mielkes liebstes Hobby". Die Welt (in German). Berlin: WeltN24 GmbH. 7 June 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Gartenschläger, Lars (31 October 2013). "Mit Mielkes Flugzeug reiste Götz Richtung Freiheit". Die Welt (in German). Berlin: WeltN24 GmbH. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Goldmann, Sven (2 November 2008). "Ein neues Leben in sechs Minuten". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin: Verlag Der Tagesspiegel GmbH. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Mit falschen Pässen in den Westen". mdr.de (in German). Leipzig: Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. 3 September 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Dirk Schlegel and Falko Götz: The East Berlin footballers who fled from the Stasi, BBC Sport, 5 November 2019

- "BFC Dynamo – AS Rom, 2:1, Europapokal der Landesmeister, 1983/1984, Viertelfinale". dfb.de (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Fußball-Bund e.V. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Voss, Oliver (29 June 2004). "Der Schiri, der hat immer Recht". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Berlin: taz Verlags u. Vertriebs GmbH. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Kleiner, John Paul (19 April 2013). "The Darth Vaders of East German Soccer: BFC Dynamo". The GDR Objectified (gdrobjectified.wordpress.com). Toronto: John Paul Kleiner. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- Dennis, Mike; LaPorte, Norman (2011). State and Minorities in Communist East Germany (1st ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-85745-195-8.

- Horeni, Michael; Reinsch, Michael (8 November 2009). "Fußballautor Leske im Gespräch: "Von Manipulationen die Schnauze voll"". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- Dennis, Mike (2007). "Behind the Wall: East German football between state and society" (PDF). German as a Foreign Language (GFL). 2007 (2): 65. ISSN 1470-9570. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Simon, Günter (5 December 1978). "BFC konterte mit besseren Chancen" (PDF). Neue Fußballwoche (FuWo) (de) (in German). Vol. 1978, no. 49. Berlin: DFV der DDR. p. 4. ISSN 0323-8407. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–341. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 57. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- Ehrmann, Johannes (3 October 2011). "Bodo Rudwaleit über die Wendezeit: "Sie riefen: Stasi-Schweine"". 11 Freunde (in German). Berlin: 11FREUNDE Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Bartz, Dietmar (8 December 2003). ""Die Stasi war nichts Spezielles"". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Berlin: taz Verlags u. Vertriebs GmbH. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- Müller, Ronny (17 January 2016). ""Der Hass hat uns stärker gemacht"". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Berlin: taz Verlags u. Vertriebs GmbH. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- "DDR-Fußball: Aus der Chronik des Deutschen Fußballverbandes der DDR (DFV)". nofv-online.de (in German). Berlin: Nordostdeutscher Fußballverband e. V. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Leske, Hanns (22 March 2006). "Foul von höchster Stelle". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin: Verlag Der Tagesspiegel GmbH. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Völker, Markus (18 July 2015). "Geschichte des BFC Dynamo: Weinrote Welt ohne gelbe Karten". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Berlin: taz Verlags u. Vertriebs GmbH. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Weinreich, Jens (24 March 2005). "Büttel an der Pfeife". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Berlin: Berliner Verlag GmbH. Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Weinreich, Jens (24 March 2005). "Der BFC Dynamo will sich seine zehn DDR-Meistertitel mit Sternen dekorieren lassen – ein historisch fragwürdiges Ansinnen: Büttel an der Pfeife". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Berlin: Berliner Verlag GmbH. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Wolf, Matthias (5 April 2005). "Der dreiste Griff nach den drei Sternen". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Geisler, Sven (9 August 2013). "Verpfiffen". Sächsische Zeitung (in German). Dresden: DDV Mediengruppe GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

Laut einer internen Analyse der Saison 1984/85 gab es in acht von 26 Spielen klare Fehlentscheidungen, die den Berlinern mindestens acht Punkte brachten. So gewinnen sie mit sechs Zählern Vorsprung auf Dynamo Dresden und Lok Leipzig zum siebenten Mal in Folge den Titel.

- Pleil, Ingolf (2013). Mielke, Macht und Meisterschaft: Dynamo Dresden im Visier der Stasi (2nd ed.). Berlin: Chrisopher Links Verlag (LinksDruck GmbH). p. 253. ISBN 978-3-86153-756-4.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Dennis, Mike (2007). "Behind the Wall: East German football between state and society" (PDF). German as a Foreign Language (GFL). 2007 (2): 67. ISSN 1470-9570. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Gröning, Marion (9 August 2013). "Verpfiffen". Sächsische Zeitung (in German). Dresden: DDV Mediengruppe GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). pp. 149–151. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- Christoph, Dickmann (10 August 2000). "Pfiff löst Aufstand aus: Der Schand-Elfmeter von Leipzig". Zeit Online (in German). No. 33/2000. Hamburg: Zeit Online GmbH. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Leske, Hanns (2012). "Schiedsrichter im Sold der Staatssicherheit". Fußball in der DDR: Kicken im Auftrag der SED (in German) (2nd ed.). Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen. ISBN 978-3-937967-91-2.

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 55. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- Dennis, Mike; LaPorte, Norman (2011). State and Minorities in Communist East Germany (1st ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-85745-195-8.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). p. 150. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- Dennis, Mike (2007). "Behind the Wall: East German football between state and society" (PDF). German as a Foreign Language (GFL). 2007 (2): 66. ISSN 1470-9570. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Leske, Hanns (2004). Erich Mielke, die Stasi und das runde Leder: Der Einfluß der SED und des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit auf den Fußballsport in der DDR (in German) (1st ed.). Göttingen: Verlag Die Werkstatt GmbH. pp. 530–533. ISBN 978-3895334481.

- Münkel, Daniela (2015). State Security: A reader on the GDR secret police (PDF). Berlin: Stasi Records Agency. p. 91. ISBN 978-3-942130-97-4. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Der DDR-Fussball". dfb.de (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Fußball-Bund e.V. 7 May 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Osterhaus, Stefan (22 May 2015). "Ins eigene Knie geschossen". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Zürich: Neue Zürcher Zeitung AG. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Crossland, David (14 January 2016). "Dynamo Berlin: The soccer club 'owned' by the Stasi". CNN International. Atlanta: Cable News Network, Inc. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Andreas Thom über Dynamo und Stasi, Partys mit DDR-Prominenz und seinen Wechsel von Ost nach West". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin: Verlag Der Tagesspiegel GmbH. 8 November 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

Und auf die Schiedsrichter gesetzt? Blödsinn. Zehnmal hintereinander Meister zu werden, das klingt vielleicht komisch, aber da steckt auch Arbeit und Können dahinter. Natürlich gab es auch mal Entscheidungen, über die wir selbst gestaunt haben.

- Lachmann, Michael (7 December 2016). "BFC-Idol Frank Terletzki: "Am schönsten waren immer unsere Siege gegen Union"". B.Z. (in German). Berlin: B.Z. Ullstein GmbH. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

Wenn man zehn Mal in Folge Meister wird, liegt das nicht daran, dass der Schiri mal ein oder zwei Minuten länger spielen ließ. Schauen Sie doch heute in die Bundesliga. Da sind drei, vier Minuten in jedem Spiel an der Tagesordnung.

- Jahn, Michael (10 April 2013). "Der große Fehler". Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Rundschau GmbH. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

'26 Spiele in einer Saison in der DDR-Oberliga kannst du nicht verschieben. Wir hatten zu dieser Zeit die fußballerisch beste Mannschaft.

- Krause, Thomas (19 January 2022). ""Der BFC Dynamo wird immer mein Club sein"". Nordkurier (in German). Neubrandenburg: Nordkurier Mediengruppe GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- "Bernd Heynemann: Momente der Entscheidung". Zeit Online (in German). Hamburg: Zeit Online GmbH. 16 March 2005. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Köster, Philipp (6 February 2012). ""Doch, das kann ich!"". 11 Freunde (in German). Berlin: 11FREUNDE Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Schäfer, Guido (11 October 2017). "Bernd Heynemann im Interview: "Wir brauchen kein Big Brother"". Sportbuzzer (in German). Hannover: Sportbuzzer GmbH. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

Der BFC ist nicht x-mal Meister geworden, weil die Schiris nur für Dynamo gepfiffen haben. Die waren schon bärenstark.

- Luther, Jörn; Willmann, Frank (2003). BFC Dynamo – Der Meisterclub (in German) (1st ed.). Berlin: Das Neue Berlin. p. 75. ISBN 3-360-01227-5.

- Kopp, Johannes (16 January 2006). "40 Jahre BFC Dynamo – "Wir sind doch sowieso die Bösen"". Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg: DER SPIEGEL GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Stolz, Sascha (7 August 2006). "Berlins große Mannschaften: Der FC Bayern des Ostens - Mit zehn Titeln in Folge stellte der BFC Dynamo in der früheren DDR einen Europa-Rekord auf". Fußball-Woche (de) (in German). Berlin: Fußball-Woche Verlags GmbH. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Dost, Robert (17 January 2011). Written at Berlin. "Der zivile Club - Die gesellschaftliche Stellung des 1.FC Union Berlin und seiner Anhänger in der DDR" (PDF) (in German). Mittweida: Hochschule Mittweida: 37–38. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Stolz, Sascha (7 August 2006). "Interview mit Jürgen Bogs". Fußball-Woche (de) (in German). Berlin: Fußball-Woche Verlags GmbH. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Glaser, Joakim (2015). Fotboll från Mielke till Merkel – Kontinuitet, brott och förändring i supporterkultur i östra Tyskland [Football from Mielke to Merkel] (in Swedish) (1st ed.). Malmö: Arx Förlag AB. p. 153. ISBN 978-91-87043-61-1.

- Gläser, Andreas (21 August 2005). "Willkommen in der Zone". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin: Verlag Der Tagesspiegel GmbH. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Veth, Manuel (27 July 2017). "Dynamo Berlin – The Rise and Long Fall of Germany's Other Record Champion". fussballstadt.com. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Schoen, Herbert (1 April 1999). "Leserbrife: Wieso war der BFC so oft DDR-Meister?". Neues Deutschland (in German). Berlin: Neues Deutschland Druckerei und Verlag GmbH. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

Herbert Schoen: Wo sind denn in dem Artikel von Herrn Wieczorek die vielen Namen von Oberligaklubs und fertigen Oberligaspielern, die in den letzten 10 BFC-Meisterjahren einen »Marschbefehl« erhielten? Selbstverständlich wurden in jungen Jahren auch viele Talente aus der Sportvereinigung Dynamo sowie kleinen Vereinen frühzeitig in den Klub delegiert. Aber außer Lauck und Doll sind keine Spieler aus anderen Oberligavereinen im Kader gewesen.

- Farshi, Sabbagh; Hadi, Mohammad (2010). Written at Hamburg. "Deutsch-Deutsche Transfers: Der Wechsel von Thomas Doll vom BFC Dynamo zum HSV 1990" (PDF) (in German). Mittweida: Hochschule Mittweida: 34–35. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Gartenschläger, Lars (14 January 2016). "50 Jahre BFC Dynamo: "Das ganze Stadion brüllte. Doll, du Schwein"". Die Welt (in German). Berlin: WeltN24 GmbH. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Thiemann, Klaus (August 1988). "Visitenkarte" (PDF). Neue Fußballwoche (de) (in German). Vol. 1988, no. Sonderausgabe. Berlin: DFV der DDR. p. 4. ISSN 0323-6420.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Goldmann, Sven (10 October 2008). "Fußball-Historie: Die Wunde von der Weser". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin: Verlag Der Tagesspiegel GmbH.

- "BFC-Legenden Jürgen Bogs und Frank Rohde erinnern sich – Dynamos Albtraum an der Weser: "Unvergessen"". DeichStube (www.deichstube.de) (in German). Syke: Kreiszeitung Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KGK. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Stier, Sebastian (13 April 2011). "Europapokal-Geschichte: Dann brannte die Tribüne". Zeit Online (in German). Hamburg: Zeit Online GmbH. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Mythos Weserstadion und seine Wunder: Die legendärsten Spiele im Stadion von Werder Bremen". Kreiszeitung (in German). Syke: Kreiszeitung Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Das zweite Wunder von der Weser – 5:0 gegen Dynamo Berlin 1988: Der Wahnsinn geht weiter". DeichStube (www.deichstube.de) (in German). Syke: Kreiszeitung Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KGK. 4 November 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Das zweite Wunder von der Weser". Weser-Kurier (in German). Bremen: WESER-KURIER Mediengruppe Bremer Tageszeitungen AG. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Bellinger, Andreas (11 October 2018). "Werder und das "Wunder von der Weser"". ndr.de (in German). Hamburg: Norddeutscher Rundfunk. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Leske, Hanns (2012). "Von der Stasi in Besitz genommen, vom Fußballvolk missachtet, in der Republik verhasst". Fußball in der DDR: Kicken im Auftrag der SED (2nd ed.). Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen. ISBN 978-3-937967-91-2.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- Stolz, Sascha (7 August 2006). "Interview mit Jürgen Bogs". Fußball-Woche (de) (in German). Berlin: Fußball-Woche Verlags GmbH. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- Feuerherm, Klaus (17 January 1990). "Dynamos bleiben grün". Junge Welt (in German). Verlag Junge Welt GmbH. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

"Wir haben darunter gelitten, daß wir praktisch eine Dreier-Leitung hatten, den DFV, die Zentrale Dynamo-Leitung und das MfS, wobei eine Minderheit über uns herrschte und uns vereinnahmte bzw. sich mit uns schmückte", formulierte Ex-Nationalspieler Noack.