Occultation (Islam)

Occultation (Arabic: غَيْبَة, ghaybah) in Shīʿa Islam refers to the eschatological belief that the Mahdi, a cultivated male descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, has already been born and subsequently went into occultation, from which he will one day emerge with Jesus (ʿĪsā) and establish global justice.

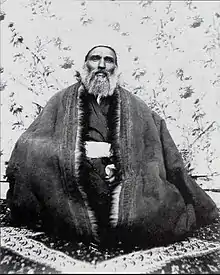

| Part of a series on Islam Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

The branches of Shīʿīsm that believe in it differ on the succession of the Imamah, and therefore which individual is in occultation, with the largest Shia branch holding it is Hujjat-Allah al-Mahdi, the twelfth Imam. The hidden Imam is still considered to be the "Imam of the Era", to hold authority over the Shīʿa community, and to guide and protect individuals and the Shīʿa community.

Twelver Shīʿīsm

In Twelver Shīʿīsm, the largest denomination within the Shīʿa branch of Islam, the twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, is believed to have undergone two occultations: the Minor Occultation, which lasted from when he is five until 874 CE, and the Major Occultation, which began in 874 CE and will last until his return.

Minor Occultation

The Minor Occultation (Arabic: ٱلْغَيْبَة ٱلصُّغْرَىٰ, al-Ghaybah aṣ-Ṣughrā) refers to the period when the Twelver Shīʿas believe the Imam still maintained contact with his followers via deputies (Arabic: ٱلنُّوَّاب ٱلْأَرْبَعَة, an-Nuwwāb al-ʾArbaʿa). During this period, lasting from 874 to 941, the deputies represented him and acted as agents between him and his followers.

Twelver Shīʿas believe that in 873, after the death of his father, the eleventh Imam, Hasan al-Askari, the twelfth Imam was hidden from the authorities of the Abbasid Caliphate as a precaution. His whereabouts were disclosed only to a select few. Four close associates of his father, known as The Four Deputies, became mediators between the hidden Imam and his followers known as Sufara until the year 941. This period is considered by Twelvers to be the first or "Minor Occultation".

When believers faced difficulty, they would write their concerns and send them to his deputy. The deputy would receive the decision of the Imam, endorse it with his seal and signature, and return it to the concerned parties. The deputies also collected Zakat and Khums on his behalf. The idea of consulting a hidden Imam was not something new for Shīʿa Muslims, because the two prior Imams had, on occasion, met with their followers from behind a curtain.

System of the Deputy

According to Twelvers, under the critical situation caused by Abbasids, Ja'far al-Sadiq was the first to base the underground system of communication in the Shīʿa community. By the time of Muhammad al-Jawad, the agents took the tactic of al-Taqiyya to take part in government. From the time of Ali al-Ridha, the Imams were under the direct control of the authorities and the direct contact between the Imam and the community was disconnected. The situation led to the increase in the role of deputies. The deputies undertook the tasks of Imams to release them from the pressure of the Abbasids.[1] Shīʿīte tradition holds that the Four Deputies acted in succession:

- Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Asadi (873–874): He was the first deputy appointed by the twelfth Imam who governed for one year;[2]

- Abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Uthman (874–916): He was the second deputy appointed by the twelfth Imam for forty-two years;[3]

- Abu al-Qasim al-Husayn ibn Ruh al-Nawbakhti (916–937): He was the third deputy appointed by the twelfth Imam for twenty-one years;[4]

- Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Muhammad al-Samarri (937–940): He was the fourth and last deputy appointed by the twelfth Imam for three years.[5]

In 941, the fourth deputy announced information from Imam Hujjat-Allah al-Mahdi that the deputy would soon die and that the deputyship would end, beginning the "Major Occultation".[6] The fourth deputy died six days later, and Twelvers continue to await the reappearance of the Mahdi. In the same year, many notable Shīʿa Muslim scholars such as Ali ibn Babawayh Qummi and Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni, the learned compiler of al-Kāfī, also died.[7]

Major Occultation

The Major Occultation (Arabic: ٱلْغَيْبَة ٱلْكُبْرَىٰ, al-Ghaybah al-Kubrā) denotes the second, longer portion of the Occultation, which continues to the present day. Shīʿa Muslims believe, based on the last Saf’ir's deathbed message, that the twelfth Imam had decided not to appoint another deputy. Thus, al-Samarri's death marked the beginning of the second or Major Occultation.[8] According to the last letter of Hujjat-Allah al-Mahdi to Ali ibn Muhammad al-Samarri:

From the day of your death [the last deputy] the period of my major occultation will begin. Henceforth, no one will see me, unless and until Allah makes me appear. My reappearance will take place after a very long time when people will have grown tired of waiting and those who are weak in their faith will say: What! Is he still alive?"[6]

Rest assured, no one has a special relationship with God. Whoever denies me is not from my (community). The appearance of the Relief depends solely upon God. Therefore, those who propose a certain time for it are liars. As to the benefit of my existence in occultation, it is like the benefit of the sun behind the clouds where the eyes do not see it. - Kitab al-Kafi, Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni[6][3]

With regard to advice for his followers during his absence, he is reported to have said: "Refer to the transmitters of our narrations, for they are my Hujjah (proof) unto yo! and I am Allah's Hujjah unto them."[7]

Secular democracy during Occultation

During the first democratic revolution of Asia, the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, the Shia Marja Akhund Khurasani and his colleagues theorized a model of religious secularity in the absence of Imam, that still prevails in Shia seminaries.[9] In absence of the ideal ruler, that is Imam al-Mahdi, democracy was the best available option.[10] He considers opposition to constitutional democracy as hostility towards the twelfth Imam.[11] He declared his full support for constitutional democracy and announced that objection to “foundations of constitutionalism” was un-Islamic.[12] According to Akhund, “a rightful religion imposes conditions on the actions and behavior of human beings”, which stem from either holy text or logical reasoning, and these constraints are essentially meant to prevent despotism.[13] He believes that an Islamic system of governance can not be established without the infallible Imam leading it. Thus the clergy and modern scholars have concluded that a proper legislation can help reduce the state tyranny and maintain peace and security. He said:[14]

Persian: سلطنت مشروعه آن است کہ متصدی امور عامه ی ناس و رتق و فتق کارهای قاطبه ی مسلمین و فیصل کافه ی مهام به دست شخص معصوم و موید و منصوب و منصوص و مأمور مِن الله باشد مانند انبیاء و اولیاء و مثل خلافت امیرالمومنین و ایام ظهور و رجعت حضرت حجت، و اگر حاکم مطلق معصوم نباشد، آن سلطنت غیرمشروعه است، چنان کہ در زمان غیبت است و سلطنت غیرمشروعه دو قسم است، عادله، نظیر مشروطه کہ مباشر امور عامه، عقلا و متدینین باشند و ظالمه و جابره است، مثل آنکه حاکم مطلق یک نفر مطلق العنان خودسر باشد. البته به صریح حکم عقل و به فصیح منصوصات شرع «غیر مشروعه ی عادله» مقدم است بر «غیرمشروعه ی جابره». و به تجربه و تدقیقات صحیحه و غور رسی های شافیه مبرهن شده که نُه عشر تعدیات دوره ی استبداد در دوره ی مشروطیت کمتر میشود و دفع افسد و اقبح به فاسد و به قبیح واجب است.[15]

English: “According to Shia doctrine, only the infallible Imam has the right to govern, to run the affairs of the people, to solve the problems of the Muslim society and to make important decisions. As it was in the time of the prophets or in the time of the caliphate of the commander of the faithful, and as it will be in the time of the reappearance and return of the Mahdi. If the absolute guardianship is not with the infallible then it will be a non-islamic government. Since this is a time of occultation, there can be two types of non-islamic regimes: the first is a just democracy in which the affairs of the people are in the hands of faithful and educated men, and the second is a government of tyranny in which a dictator has absolute powers. Therefore, both in the eyes of the Sharia and reason what is just prevails over the unjust. From human experience and careful reflection it has become clear that democracy reduces the tyranny of state and it is obligatory to give precedence to the lesser evil.”

— Muhammad Kazim Khurasani

As “sanctioned by sacred law and religion”, Akhund believes, a theocratic government can only be formed by the infallible Imam.[16] Aqa Buzurg Tehrani also quoted Akhund Khurasani saying that if there was a possibility of establishment of a truly legitimate Islamic rule in any age, God must end occultation of the Imam of Age. Hence, he refuted the idea of absolute guardianship of jurist.[17] Therefore, according to Akhund, Shia jurists must support the democratic reform. He prefers collective wisdom (Persian: عقل جمعی) over individual opinions, and limits the role of jurist to provide religious guidance in personal affairs of a believer.[18] He defines democracy as a system of governance that enforces a set of “limitations and conditions” on the head of state and government employees so that they work within “boundaries that the laws and religion of every nation determines”. Akhund believes that modern secular laws complement traditional religion. He asserts that both religious rulings and the laws outside the scope of religion confront “state despotism”.[19] Constitutionalism is based on the idea of defending the “nation’s inherent and natural liberties”, and as absolute power corrupts, a democratic distribution of power would make it possible for the nation to live up to its full potential.[20]

Ismāʿīlīsm

Ismāʿīlīs, otherwise known as Sevener, derive their name from their acceptance of Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar as the divinely appointed spiritual successor (Imam) to Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the 6th Shīʿīte Imam, wherein they differ from the Twelvers, who recognize Mūsā al-Kāẓim, younger brother of Ismāʿīl, as the true Imam.

Sevener Shīʿīsm

Before the rise of the Fatimid Caliphate, a small group of Ismāʿīlīs, the Qarmatians, believed that Muhammad ibn Imam Ismāʿīl had gone into Occultation in the 8th century CE, and were called Seveners to reflect their belief in only seven Imams (Muhammad's father Ismāʿīl being the last until his return). The Qarmatians accepted a Persian prisoner by the name of Abu'l-Fadl al-Isfahani, who claimed to be the descendant of emperors, as the returned Muhammad ibn Imam Ismāʿīl[21][22][23][24][25][26] and also as the Mahdi. The Qarmatians rampaged violently across the Middle East in the 10th century CE, climaxing their bloody campaign with the stealing of the Black Stone from the Kaaba in Mecca in 930 CE under Abu Tahir al-Jannabi. After the arrival of the Mahdi, they changed their qibla from the Kaaba to the Zoroastrian-influenced fire. After their return of the Black Stone in 951 CE and defeat by the Abbasids in 976 CE, they slowly faded out of history and no longer have any adherents.[27]

Musta‘lī Shīʿīsm

According to Ṭayyibi Ismāʿīlīs, during the current Occultation of the 21st Imam, Al-Ṭayyib Abū'l-Qāsim, a Da'i al-Mutlaq ("Unrestricted Missionary") maintains contact with him.[28] The several branches of the Musta‘lī Ismāʿīlīs differ on who the current Da'i al-Mutlaq is.[29]

Nizārī Shīʿīsm

The Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs believe that there is no Occultation at all, and that the Aga Khan IV is the 49th Imam.[30] They believe that the Imam's authority is no different from the authority of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, the first Imam. The Aga Khan IV currently provides guidance to the Nizārī community on worldly and spiritual matters.[29]

Waqifi Shīʿīsm

According to Waqifi Seveners, there are other reasons for the Occultation: the twelfth Imam not being proud of himself and continues to examine world events and make evaluations, only to be loyal and reverent to Allah, which is also in Occultation; the other Muslims sects are to be judged by the Mahdi through the guidance of Allah.

Zaydī Shīʿīsm

The Zaydī Shīʿas, otherwise known as Fivers, believe that there is no Occultation at all, and that any descendant of Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī or Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī could become the twelfth Imam. The twelfth Imam must rise up against oppression and injustice and rule as a visible and just ruler.[31]

Other views

Scholarly observations

Some scholars of Islamic studies, including the British historian Bernard Lewis, point out that the concept of an Imam hidden in Occultation was not new in 873 CE; rather, it was a recurring factor in the history of Shīʿa Islam. Examples of this include the cases of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah (according to the Kaysanites), Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya, Musa al-Kadhim (according to the Waqifite Shīʿas), Muhammad ibn Qasim al-Alawi, Yahya ibn Umar, and Muhammad ibn Ali al-Hadi.[32]

Baháʼí views

The Baháʼí Faith is a distinct monotheistic universal Abrahamic religion that developed in 19th-century Persia, originally derived as a splinter group from Bábism, another distinct monotheistic Abrahamic religion, itself derived from Twelver Shīʿīsm.[33][34] In the Baháʼí Faith, which regards the Báb as the "spiritual return" of the Mahdi,[35] Bahá'u'lláh and `Abdu'l-Bahá considered the story of the Occultation of the twelfth Imam in Twelver Shīʿīsm to have been a pious fraud conceived by a number of the leading Shīʿa clergymen in order to maintain the coherence and continuity of the Shīʿa movement after the death of the 11th Imam, Hasan al-Askari.[36] Bahá'ís believe that Sayyid Ali Muhammad Shirazi, known as the Báb, is the "spiritual return" of the twelfth Imam, the Mahdi, who had already made his advent and fulfilled all the prophecies. Multiple sources claim that the Báb recanted his claim under trial,[37][38] which is rejected by his followers.[39] The Báb was publicly executed on 9 July 1850.[40] The Báb repeatedly talked about a messianic figure in his writings, called "He Whom God shall make manifest", that would appear after him and would be the origin of all divine attributes.[41] Baháʼís and Bábis don't consider themselves as Muslims, since both of their religions have superseded Islam, and aren't considered as such by Muslims either; rather, they are seen as apostates from Islam.[33][34] Since both Baháʼís and Bábis reject the Islamic dogma that Muhammad is the last prophet, they have suffered religious discrimination and persecution both in Iran and elsewhere in the Muslim world due to their beliefs.[34] (See: Persecution of Baháʼís).

Druze views

The Druze are a distinct monotheistic Abrahamic religion and ethno-religious group that developed in the 11th century CE originally as an offshoot of Ismāʿīlīsm.[42] The Druze believe the Imam Al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh went into the Occultation after he disappeared in 1021 CE, followed by the four founding divine callers (da‘wat at-tawḥīd) of the Druze religion, including Hamza ibn ʾAlī ibn Aḥmad, leaving the leadership to a fifth leader called Bahāʾ al-Dīn. The Druze refused to acknowledge the successor of Al-Ḥākim as an Imam but accepted him as a caliph.[43] The Druze faith further split from Ismāʿīlīsm as it developed its own unique doctrines, and finally separated from both Ismāʿīlīsm and Islam altogether;[42] these include the belief that Al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh was God incarnate.[44] In fact, the Druze don't identify themselves as Muslims,[42] and aren't considered as such by Muslims either.[42]

See also

Bibliography

- AḴŪND ḴORĀSĀNĪ, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (March 2015). Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815633884. OCLC 931494838.

- Sayej, Caroleen Marji (2018). Patriotic Ayatollahs: Nationalism in Post-Saddam Iraq. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 67. doi:10.7591/cornell/9781501715211.001.0001. ISBN 9781501714856.

- Hermann, Denis (1 May 2013). "Akhund Khurasani and the Iranian Constitutional Movement". Middle Eastern Studies. 49 (3): 430–453. doi:10.1080/00263206.2013.783828. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 23471080.

- Bayat, Mangol (1991). “Iran's First Revolution: Shi'ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909”. Studies in Middle Eastern History. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506822-1.

References

- Hussain, Jassim M. (1982). The occultation of the Twelfth Imam. London, England: Muhammadi Trust. ISBN 978-0-907794-01-1.

- Mohammed Raza Dungersi. A Brief Biography of Imam Muhammad bin Hasan (a.s.): al-Mahdi. Bilal Muslim Mission. pp. 19–21.

- Association of Imam Mahdi. Special Deputies.

- Zahra Ra'isi (2013). "The Special Deputies of Imam Mahdi (as)" (PDF). Message of Thaqalayn. 14 (1): 80.

- Ronen A. Cohen (12 February 2013). The Hojjatiyeh Society in Iran: Ideology and Practice from the 1950s to the Present. p. 15. ISBN 9781137304773.

- Zahra Ra'isi. The Special Deputies of Imam Mahdi (as) (PDF). p. 82.

- Hussain, Hussain M. (1982). The Holy Qur'an. The Muhammadi Trust of Great Britain & Northern Ireland. 0-907794-01-7. Archived from the original on 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- "The Occultation of the Twelfth Imam (A Historical Background)". Al-Islam.org. Archived from the original on 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- Ghobadzadeh, Naser (December 2013). "Religious secularity: A vision for revisionist political Islam". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 39 (10): 1005–1027. doi:10.1177/0191453713507014. ISSN 0191-4537.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 152.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 159.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 160.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 161.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 162.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص ۲۱۴-۲۱۵، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Hermann 2013, pp. 434.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 220.

- Hermann 2013, pp. 436.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 166.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 167.

- Abbas Amanat, Magnus Thorkell. Imagining the End: Visions of Apocalypse. p. 123.

- Delia Cortese, Simonetta Calderini. Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam. p. 26.

- Abū Yaʻqūb Al-Sijistānī. Early Philosophical Shiism: The Ismaili Neoplatonism. p. 161.

- Yuri Stoyanov. The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy.

- Gustave Edmund Von Grunebaum. Classical Islam: A History, 600-1258. p. 113.

- Yuri Stoyanov. The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy.

- "Qarmatiyyah". Archived from the original on 2007-04-28. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- 'Aqeedat ul-Muwahhedeen wa Muzehato Maraatib Ahl id-Deen: 8th Da’i-e-Mutlaq Saiyedna Husain bin Saiyedna Ali bin Mohammad al-Waleed (d. 667 AH/1269 AD)

- Cornell, Vincent J. (2007). Voices of Islam. Praeger (December 30, 2006). ISBN 978-0275987329.

- Essential Islam: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice. Praeger (November 12, 2009). 2010. ISBN 978-0313360251.

- Islamic Dynasties of the Arab East: State and Civilization during the Later Medieval Times by Abdul Ali, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., 1996, p97

- The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam, Bernard Lewis, pp. 23, 35, 49.

- Cole, Juan (30 December 2012) [15 December 1988]. "BAHAISM i. The Faith". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III/4. New York: Columbia University. pp. 438–446. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_6391. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Osborn, Lil (2021). "Part 5: In Between and on the Fringes of Islam – The Bahāʾī Faith". In Cusack, Carole M.; Upal, M. Afzal (eds.). Handbook of Islamic Sects and Movements. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 21. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 761–773. doi:10.1163/9789004435544_040. ISBN 978-90-04-43554-4. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Cole, Juan. "I am all the Prophets". Juan Cole's homepage at the server of University of Michigan. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- Momen, Moojan. Shi`i Islam and the Baháʼí Faith Archived 2014-01-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Browne, Edward Granville (1918). Materials for the Study of the Babi Religion. Cambridge [Eng.] The University Press Publication. ISBN 1152573691.

- Ali, Muhammad (1997). History and Doctrines of the Babi Movement. USA: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam (Lahore). pp. 7–8. ISBN 0913321478.

- MacEoin, Dennis (2000). "The trial of the Bab: Shi'ite orthodoxy confronts its mirror image". In Hillenbrand, Carole (ed.). Studies in Honour of Clifford Edmund Bosworth Vol II. The Sultan's Turret: Studies in Persian and Turkish Culture. EJ Brill. pp. 272–317. ISBN 978-9004110755.

- Nabil. The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl's Narrative of the Early Days of the Baháʼí Revelation. p. 515. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- Buck, Christopher (2004). "The eschatology of Globalization: The multiple-messiahship of Bahā'u'llāh revisited". In Sharon, Moshe (ed.). Studies in Modern Religions, Religious Movements and the Bābī-Bahā'ī Faiths. Boston: Brill. pp. 143–178. ISBN 90-04-13904-4.

- Timani, Hussam S. (2021). "Part 5: In Between and on the Fringes of Islam – The Druze". In Cusack, Carole M.; Upal, M. Afzal (eds.). Handbook of Islamic Sects and Movements. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 21. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 724–742. doi:10.1163/9789004435544_038. ISBN 978-90-04-43554-4. ISSN 1874-6691.

- The Druzes: An Annotated Bibliography by Samy Swayd, Kirkland WA USA: ISES Publications(1998). ISBN 0-9662932-0-7.

- Poonawala, Ismail K. (July–September 1999). "Review: The Fatimids and Their Traditions of Learning by Heinz Halm". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 119 (3): 542. doi:10.2307/605981. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 605981. LCCN 12032032. OCLC 47785421.