Fugitive Slave Convention

The Fugitive Slave Law Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, August 21–22, 1850.[1][2] Organized to oppose passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 by the United States Congress, participants included Frederick Douglass, the Edmonson sisters, Gerrit Smith, Samuel Joseph May, Theodore Dwight Weld, and others.[2]

The convention opened at the First Congregational Church of Cazenovia (now Cazenovia College's theater building), but because there were too many attendees for that venue, itmoved the next day to "the orchard of Grace Wilson's School, located on Sullivan Street."[2] Although there were in 1850s no railroads in Cazenovia, it was said to have had 2000 to 3000 participants.[2][1]—the population of Cazenovia at the time was 2,000.

The meeting was chaired by Douglass.[1] The local links with the abolitionist movement were Theodore Weld's brother Ezra Greenleaf Weld, who owned a daguerrotype (photography) studio in Cazenovia and to whom we owe a picture of the principal attendees. Even more important, the abolitionist philanthropist Gerrit Smith, one of the Secret Six that years later would finance John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, lived only 10 miles (16 km) away, in more rural Peterboro. The first book on Madison County, of 1899, says much of Smith, but mentions neither the Convention nor Ezra Weld.[3]

John Brown "made a very fiery speech" about his need of funds to buy arms for his and his sons' use fighting slavery in Kansas; funds were contributed on the spot, principally by Gerrit Smith.[4]

A hostile newspaper report refers to the meeting as "Gerrit Smith's Convention".[5]

Call for the convention

The following announcement appeared in the August 1, 1850, issue of the National Anti-Slavery Standard:

- Such persons as have escaped from Slavery, and those who are resolved to stand by them, are invited to meet for mutual counsel and encouragement at Cazenovia, Madison County, New York, on Wednesday, 21st of August, 1850. The assembling will take place at 10 o'clock A. M. in the Independent Church, and the meeting will continue through two days. The object aimed at on the occasion will not be simply an exchange of congratulations and an expression of sympathy, but an earnest consideration of such subjects as are pertinent to the present condition and prospects of the slave and free colored population of the country, and to the relations, which good and true men sustain to the cause of impartial freedom and justice. Friends! shall not this be made a grand event? Shall not the channels of former sympathies be opened anew? Will not they of the “old guard” delight to look each other in the face once more, and renew their vows upon a common altar? Let them come from every quarter—freemen, free women, and fugitives! They are bid a most cordial welcome by the good people of Cazenovia. There are friends, hospitalities, meeting houses, and beautiful groves there! Let all come, who have a heart and can!

- In befalf of the New York State Vigilance Committee,

Gerrit Smith, Prest. [sic]

Charles B. Ray, Sec.[6]

It was promptly reprinted in William Garrison's Liberator[7] and Frederick Douglass's North Star.[8]

According to a newspaper report, about 30 fugitive slaves were in attendance.[9]

Convention proceedings

During the convention, William L. Chaplin was discussed.[10] Chaplin was a radical political abolitionist who helped plan the escape of 77 slaves from Washington, D.C.[11] This plan ultimately failed and later, Chaplin was arrested after he was caught driving a carriage with two escaped slaves.[11] His fiancée, Theodosia Gilbert, attended the convention.[11] There was a resolution by James C. Jackson that was adopted to create a committee to raise money in order to liberate Chaplin.[10] He advised them to raise 20,000 dollars in 30 days.[10] They also called upon the Liberty Party to nominate Chaplin as its candidate in the 1852 presidential election.[12]

An open letter titled “To American Slaves from Those Who Have Fled from American Slavery” was introduced to the attendees by Gerrit Smith.[13] This letter advocated for the abolition of slavery and even the use of violence in order to escape.[13] It also discusses the current situation of the country with the Fugitive Slave Law enacted and presents 17 resolutions which they adopted during the convention.[10] These resolutions outlined the evils of slavery, the greatness of abolitionists like William L. Chaplin, and the convention's commitment to support other organizations and people who support abolition and African-Americans.[10]

Convention leadership and groups

The meeting started out with temporary chairman Samuel Joseph May and temporary secretary Samuel Thomas Jr.[10] May then appointed Samuel Wells, J.W. Loguen, and Charles B. Ray to a committee to nominate official officers.[10] Later in the convention, official officers were appointed by this committee to major positions. Frederick Douglass was appointed to president.[10] Joseph C. Hathaway, Francis Hawley, Chas. B. Ray, and Chas. A. Wheaton were appointed for vice presidents.[10] Charles D. Miller and Anne V. Adams were appointed for secretaries.[10]

Joseph C. Hathaway, William R. Smith, Eleazer Seymour, and James C. Jackson were appointed to nominate people for the “Chaplin Committee”.[10] This committee ended up consisting of around 19 people.[10] Some of the committee members included James C. Jackson, Joseph C. Hathaway, William R. Smith, and George W. Lawson.[10]

A group of women including Mrs. F. Rice, Phebe Hathaway, and Louisa Burnett were appointed to nominate a committee of females.[10] This committee would obtain a silver pitcher and two silver goblets to present them to William C. Chaplin, in honor of “his distinguished services in the cause of humanity.”[10]

Subsequent meetings

Further meetings were announced in Canastota (October 23), Cazenovia (October 25), Hamilton (October 30), and Peterboro (November 1).[14]

Many of the participants of this convention were also involved in a later anti-fugitive slave law meeting in Syracuse, New York, on Tuesday, January 7, 1851.[15]

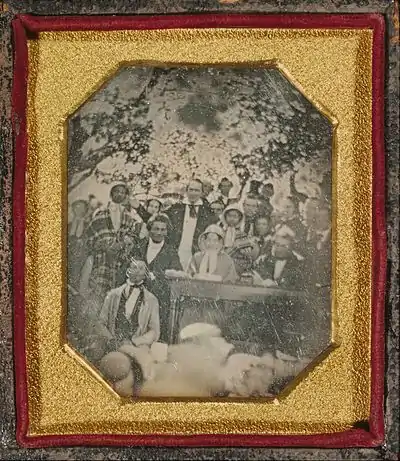

The daguerreotype

There is one and only one visual image of the meeting, in the daguerreotype held by the Madison County Historical Society, with a copy (image flipped) in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. It was taken by Ezra Greenleaf Weld, Theodore's brother, who owned a daguerrotype studio in Cazenovia.

Daguerrotypes could not be taken casually, as those being photographed had to hold themselves immobile for some seconds. That of the Cazenovia Convention is a formal group picture, outdoors because of the sunlight. It was intended for the eyes of William L. Chaplin, in jail in Washington for having assisted two slaves in an unsuccessful escape attempt. Chaplin's future wife, Theodosia Gilbert Chaplin, is seated at the table with pen and paper in hand, documenting through the picture that "the document" was indeed prepared by the group. To her left is Frederick Douglass; to her right, also with pen, is Joseph Hathaway; behind her stands Gerrit Smith,[16] flanked by the Edmonson sisters. One of the sisters, probably Mary, addressed the crowd. One audience member described her as a "young and noble-hearted girl", using "words of simple and touching eloquence".[17]

External links

References

- Baker, Robert A. (4 February 2005). "Cazenovia convention: A meeting of minds to abolish slavery". The Post-Standard. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Weiskotten, Daniel H. (25 May 2003). "The 'Great Cazenovia Fugitive Slave Law Convention' at Cazenovia, NY, August 21 and 22, 1850". RootsWeb. Ancestry.com. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Smith, John E. (1899). Our country and its people; a descriptive and biographical record of Madison County, New York. Boston: Boston History Company.

- "Old John Brown". Herald of Freedom (Lawrence, Kansas). October 29, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Gerrit Smith's Convention". Lehigh Register (Allentown, Pennsylvania). August 29, 1850. p. 2 – via Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive.

- "Liberty—Equality—Fraternity!!! Fugitives from the Prison-House of Southern Despotism with their friends and protectors in council!". National Anti-Slavery Standard. August 1, 1850. p. 39 – via accessible-archives.com.

- "Liberty—Equality—Fraternity!!! Fugitives from the Prison-House of Southern Despotism with their friends and protectors in council!". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. August 9, 1850. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Liberty—Equality—Fraternity!!! Fugitives from the Prison-House of Southern Despotism with their friends and protectors in council!". The North Star. Rochester, New York. August 15, 1850. p. 2.

- "Abolition Convention". Carlisle Herald (Carlisle, Pennsylvania). August 28, 1850. p. 2 – via Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive.

- Foner, Philip S., ed. (1979). Proceedings of the Black State Conventions, 1840-1865: Volume 1. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 43–53.

- Harrold, Stanley. "The Cazenovia Convention". Historians Against Slavery. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "The fugitive slaves who are this day assembled in Cazenovia, N.Y." (September 5, 1850). "To the Liberty Party". The North Star. Rochester, New York. p. 3.

- "Site of Fugitive Slave Law Convention". Freethought Trail. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "5000 Men and Women Wanted". Madison County Whig. Cazenovia, New York. October 16, 1850. p. 5 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- "Anti-Fugitive Slave Law State Convention". New York Daily Tribune. January 9, 1851. p. 4.

- Culclasure, Scott P. (1999). "Chapter 7: Interpreting the Past with Light and Shadow". The Past as Liberation from History. Counterpoints, 63. Peter Lang. pp. 123–139, at p. 132. ISBN 9780820438405. JSTOR 42975609.

- "The Edmonson Sisters" (PDF). Saving Washington: The New Republic and Early Reformers, 1790–1860. Women and the American Story. New York Historical Society. 2017.