Flood v. Kuhn

Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that preserved the reserve clause in Major League Baseball (MLB) players' contracts. By a 5–3 margin, the Court reaffirmed the antitrust exemption that had been granted to professional baseball in 1922 under Federal Baseball Club v. National League, and previously affirmed by Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc. in 1953. While the majority believed that baseball's antitrust exemption was anomalous compared to other professional sports, it held that any changes to the exemption should be made through Congress and not the courts.

| Flood v. Kuhn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 20, 1972 Decided June 19, 1972 | |

| Full case name | Curt Flood v. Bowie Kuhn, et al. |

| Citations | 407 U.S. 258 (more) 92 S. Ct. 2099; 32 L. Ed. 2d 728; 1972 U.S. LEXIS 138 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Preliminary injunction denied, 309 F. Supp. 793 (S.D.N.Y. 1970); 316 F. Supp. 271 (S.D.N.Y. 1970); affirmed, 443 F.2d 264 (2d Cir. 1971); cert. granted, 404 U.S. 880 (1971). |

| Holding | |

| Professional baseball is in fact interstate commerce under the Sherman Antitrust Act, but congressional acquiescence in previous jurisprudence to the contrary make it the legislative branch's responsibility to end or modify antitrust exemption unique among professional sports. Second Circuit affirmed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Blackmun, joined by Stewart, Rehnquist (in full); Burger, White (all but part I) |

| Concurrence | Burger |

| Dissent | Douglas, joined by Brennan |

| Dissent | Marshall, joined by Brennan |

| Powell took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

| Laws applied | |

| Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1291–1295 | |

The National League had instituted the reserve clause in 1879 as a means of limiting salaries by keeping players under team control. Under the new system, a baseball team reserved players under contract for a year after the contract expired, limiting them from being taken by other teams in bidding wars. MLB team owners argued that the clause was necessary to ensure a competitive balance among teams, as otherwise wealthier clubs would outbid teams in smaller markets for star players. The reserve clause was not addressed in Federal Baseball, where Ned Hanlon, owner of the rival Federal League's (FL) Baltimore Terrapins, had argued that MLB had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act through anticompetitive practices meant to force the FL out of business. The Supreme Court ruled that baseball did not qualify as interstate commerce for the purposes of the Sherman Act, a ruling that remained even after it denied boxing and American football the same exemption.

In 1969, Curt Flood, a center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals, was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. Flood was unhappy with the trade, as the Phillies had a poor reputation for their treatment of players, but the reserve clause required him to play for Philadelphia. He retained attorney Arthur Goldberg, a former Supreme Court justice, through Marvin Miller and the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) and took the case to court, arguing that the reserve clause was a collusive measure that reduced competition and thus an antitrust violation. The reserve system was upheld by district, appellate, and the Supreme Court under the principle of stare decisis and the precedents set by Federal Baseball and Toolson.

Legal scholars have criticized the Court's decision in Flood both for its rigid application of stare decisis as well as Section I of Harry Blackmun's majority opinion, an "ode to baseball" that contains little legal matter. The reserve clause was settled outside the Supreme Court three years later through the arbitration system created by the collective bargaining agreement between MLB and the MLBPA. Peter Seitz ruled in favor of Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally that their contracts could only be renewed without their permission for one season, after which they became free agents. Free agency in MLB was codified the following year after the 1976 Major League Baseball lockout, while the Curt Flood Act of 1998, signed by Bill Clinton, partially reversed baseball's antitrust exemption as it related to interactions between players and owners.

Background

Reserve clause

William Hulbert, then the president of the National League (NL), instituted the first reserve clause in professional baseball in 1879.[1] Under Hulbert's system, each NL team could "reserve" five players for its roster, and owners from opposing clubs could not offer contracts to reserved players.[2] This provision extended to 11 players per team in 1883, 12 per team in 1885, 14 per team in 1887,[3] and by 1890, all players under active contract with an NL team were subject to the reserve clause.[4] Any player who signed with an NL team was placed under that team's control until they retired, were traded to another club, or were released outright.[5] This latter qualification also made it easier for teams to discipline players by voiding their contracts, and it was sometimes referred to as the "reserve and release" clause.[4] In 1883, the American Association entered into the first national agreement with the NL, extending the reserve system to the Association as well.[6] In 1903, the American League (AL) signed its own national agreement, forming the two-league system known as Major League Baseball (MLB). The reserve clause extended cross-league, with reserved NL players prevented from joining AL teams and vice versa.[7]

The primary rationale for instituting the reserve clause was to limit player salaries for the struggling NL by keeping players under team control.[3] Many of the players that the owners reserved for the 1880 season had been, at the time, the best-paid in the league, such as Cap Anson, Paul Hines, and Tommy Bond, and these players saw their salaries drop once they remained bound to their respective teams.[8] Once the reserve system was extended to all players, those players were categorized into five categories under the Brush Classification System, with each group receiving a salary that ranged between $1,500 and $2,500 annually.[9] While the league owners supported the reserve system as a cost-cutting measure, they also defended its use as a way to ensure a competitive balance in baseball. Without a reserve clause, the wealthiest teams could stockpile star players simply by outbidding smaller teams.[10] This sentiment was echoed by federal district court judge William P. Wallace in 1890, who quoted Albert Spalding in arguing that the rule "takes a manager by the throat and compels him to keep his hands off his neighbor's enterprise".[11] The owners also argued that the reserve clause justified a team's investment in its players, who were drafted with little experience and required years of development to reach the major leagues.[12]

One of the first players to challenge the reserve clause was Sam Wise, who in 1882 left the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the American Association for the NL's Boston Red Caps. The Massachusetts General Court denied Cincinnati's request for an injunction, and Wise spent the remainder of the season with Boston.[13] The reserve clause's most vocal opponent, however, was John Montgomery Ward, known as Monte Ward, who compared the system to slavery in 1885.[14] In 1890, he helped to found the Players' League (PL), which promised a three-year contract to all players and no pay cuts after the first year.[15] Players' salaries were the same as what the NL had paid them in either 1888 or 1889, whichever was higher.[16] Players who had joined the PL, like Jim O'Rourke, were able to convince their colleagues that the reserve clause only prevented players from joining teams in those leagues that had it, and that they were legally free to join teams in new leagues.[17]

When Ward left the New York Giants to join the PL, the team took him to New York Supreme Court[lower-alpha 1] to prevent him from playing with his new club.[16] While Justice Morgan J. O'Brien disagreed with Ward and O'Rourke's assessment that the reserve clause did not apply to the Players' League, the court was most concerned about the vague phrasing of the clause: Ward was technically under contract with the Giants for the 1890 season, but the perpetual reserve clause meant that major aspects of his contract, including his salary, were not addressed, and the court decided that the reserve clause was "too indefinite" to be properly enforced.[16] The decision in Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ward also criticized the uneven system by which a team could hold a player theoretically indefinitely but terminate them with only 10 days' notice.[18][19] This legal victory was not enough to sustain the Players' League, as many of its financial backers pulled out after suffering considerable losses during that premiere season.[20]

Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie was taken to court in 1901 by the Philadelphia Phillies, an NL team, after he joined their crosstown AL rival, the Philadelphia Athletics,[21] who were not yet bound by the reserve clause. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled the next year in Philadelphia Ball Club, Ltd. v. Lajoie[22] that he possessed a unique skill set, much like Johanna Wagner, the defendant in the seminal 1852 English contract law decision Lumley v Wagner.[23] This skill set meant that, while the Phillies could not require Lajoie to play for them, they could prevent him from playing for other teams.[24]

Baseball's antitrust exemption

The United States Congress had enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act which prohibited the type of anticompetitive collusion under which the reserve clause has been argued to fall, in 1890.[11] This policy was extended even further by the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which allowed private parties to sue for damages caused by anticompetitive conduct.[25] The same year that the Clayton Act became law, the Federal League (FL) was created as a challenger to MLB.[26] Despite the new league prohibiting players from signing if they were under contract with a major league team and MLB threatening to blacklist players who defected, players such as Joe Tinker nonetheless left MLB to join the FL, and many of these defections led to litigation. While the lower courts typically ruled in favor of players who joined the Federal League during the offseason, when they were under reserve but not an active contract, the owners did win some cases where players had abandoned their MLB team midseason.[27]

Dave Fultz, the president of the Federal League,[28] was primarily focused on improving the working conditions of minor league players and improving player safety. He was not radically against the reserve system, and he feared that eliminating it from his league would incur retribution from MLB. Instead, he proposed that Federal League players remained under reserve for five years, after which owners and players could mutually agree to extend the reserve option.[29]

Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League

In January 1915, the Federal League owners sued the major leagues and three members of the National Commission for antitrust violations, hoping that noted trustbuster Kenesaw Mountain Landis would rule in their favor. Landis, however, announced that "any blows at the thing called baseball would be regarded by this court as a blow to a national institution", and he took the case under advisement for a year to stall any action.[30] Meanwhile, the FL incurred great financial losses that season, and came to a settlement with MLB at the end of the year.[30]

Most FL owners were bought out by MLB teams or allowed to buy interests in existing major league clubs. The one exception was Ned Hanlon of the Baltimore Terrapins. Hanlon and his partners brought an antitrust lawsuit in D.C. District Court, alleging that MLB had colluded to "wreck and destroy" the FL by purchasing and dissolving its teams.[31][32] Judge Wendell Phillips Stafford ruled in Hanlon's favor, agreeing that baseball games constituted interstate trade and commerce under the Sherman Act and that MLB had engaged in impermissibly monopolistic behavior. Hanlon was awarded $80,000 in damages, which was increased to $240,000 ($6.43 million in modern dollars[33]) under the treble-damages provision of the Clayton Act.[34]

On appeal, Judge George W. Pepper of the D.C. Circuit held that sports like baseball, "a spontaneous product of human activity", were "not in [their] nature commerce", and thus not subject to antitrust legislation.[35] The circuit's chief judge, Constantine Joseph Smyth, wrote in his opinion that "sport" such as professional baseball fell outside the realm of business and thus monopoly.[34] Hanlon then brought his claim to the Supreme Court, where former US president and baseball fan William Howard Taft was Chief Justice.[35]

In May 1922, the Court unanimously affirmed the appellate decision in Federal Baseball Club v. National League.[35] The Sherman Act required that businesses be engaged in interstate commerce to incur government intervention,[36] and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. interpreted commerce to include only physical goods. Because baseball exhibitions did not fall under this definition, the sport consisted of "purely state affairs".[37][38][lower-alpha 2]

The next term the Court considered Hart v. B.F. Keith Vaudeville Exchange, a Clayton Act suit brought by a talent agent alleging the defendants had conspired to exclude the plaintiffs' clients from the many theaters they controlled in order to extract large payments to them, arguing that since their productions depended on the interstate transport of sets and costumes, the vaudeville circuit was interestate commerce. It had been filed before Federal Baseball; afterwards, the defendants had argued that their industry, too, was similarly not interstate commerce since its main business activity was selling admission to performances it had arranged rather than transport of goods for sale, with the shipments of materials required for those productions merely an incident to their business, just as with baseball teams' travel. The Southern District of New York agreed and dismissed the case. Justice Holmes wrote for a unanimous Court that reversed the trial court on jurisdictional grounds, holding that a federal question existed over whether the vaudeville circuit was interstate commerce, and that until that question was resolved the case was not to be disposed even if the arguments for federal jurisdiction themselves seemed weak. "[I]t may be that what in general is incidental, in some instances may rise to a magnitude that requires it to be considered independently", Holmes wrote.[41]

Gardella v. Chandler

The case that came closest to overturning the reserve system and antitrust exemption was brought by Danny Gardella, who left the New York Giants in 1946 to play for the Azules de Veracruz of the Mexican League.[42] He returned to New York in 1947 to play in MLB again but found himself blacklisted.[43] Gardella's attorney Frederic Johnson tried to distinguish his client from Nap Lajoie by arguing his client was not an exceptional player or "unique performer", but a standard-quality professional athlete being denied an opportunity to make a living.[44]}}

Judge Henry W. Goddard of the Southern District of New York ruled in favor of the owners, dismissing Gardella's lawsuit under the precedent set by Federal Baseball,[43][45] The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit overturned this decision, however, with Jerome Frank ruling that baseball's television and radio presence made it a matter of interstate commerce that thus fell under the Sherman Act.[46] The case never reached the Supreme Court, as Happy Chandler, then the Commissioner of Baseball, soon reinstated the blacklisted Mexican League players. Gardella settled out of court for $60,000 in damages and a trade to the St. Louis Cardinals.[47]

With Gardella's case settled, there was little pressure on the league to alter the reserve system or any other anticompetitive measures.[48] Some members of Congress, however, were worried about the potential challenge to baseball's antitrust exemption, as well as the instability to the sport caused when Chandler was replaced by Ford Frick.[49] In 1951, four bills were introduced to Congress that would have further codified the antitrust laws concerning baseball.[50]

Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc.

Congress ultimately took no action on the antitrust exemption, as the House Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power decided that enacting official legislation would affect the Supreme Court's decision on another case that had come its way, Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc.[51] George Toolson, a minor league player in the Yankees' farm system, had been reassigned from the Newark Bears, their Triple-A affiliate, to the Low-A Binghamton Triplets in 1949.[52] He refused to report to the new club and brought the reserve clause to court as an antitrust violation.[53] In a 7–2 ruling, the Court upheld the Federal Baseball precedent that the "business of giving exhibitions" was "purely state affairs" and thus exempt from the antitrust protections built into the Sherman Act.[54] The one-paragraph per curiam majority opinion in Toolson[55] held that any changes to the Federal Baseball precedent would have to go through Congress and not the courts.[56] [50] Justice Harold Hitz Burton dissented, arguing that organized baseball was obviously engaged in interstate trade and commerce and thus should be subject to federal antitrust enforcement.[57][58]

After Toolson

The Court did not revisit baseball's antitrust exemption, although other lower courts would. In the years after Toolson, three other antitrust cases involving other industries, including other professional sports, made baseball's exemption problematic when the Court declined to extend the logic of Federal Baseball to them.

Early in 1955, two cases decided the same day involved federal Sherman Act cases against companies alleged to have nearly monopolized theatrical performances and professional boxing. Both defendants had argued that the Federal Baseball precedent applied to them as well since the interstate travel required to stage performances and fights was equally incidental to those events, and judges in the Southern District of New York hearing the cases granted defense motions to dismiss. The government appealed directly to the Supreme Court under the Expediting Act.[59][60]

In both cases, the Court allowed the cases to proceed. The theater case, United States v. Shuster, was decided unanimously. After citing many precedents which had held industries which did not ship goods for sale across state lines to be interstate commerce, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that Federal Baseball and Toolson applied only to baseball and thus Hart controlled in the instant case: "[It] established, contrary to the defendants' argument here, that Federal Baseball did not automatically immunize the theatrical business from the antitrust laws." Any holding that it did required a trial on that question. Justices Burton and Reed referred to their Toolson dissents in statements indicating their concurrence with Warren's opinion.[61]

The two would also join Warren's majority opinion in United States v. International Boxing Club of New York, Inc., where he conceded that "if it were not for Federal Baseball and Toolson, we think that it would be too clear for dispute that the Government's allegations bring the defendants within the scope of the Act." Again he deferred to Congress to resolve the issue if it desired.[62] Justices Felix Frankfurter and Sherman Minton dissented this time, with Minton also joining Frankfurter's dissent.[63]

"It would baffle the subtlest ingenuity to find a single differentiating factor between other sporting exhibitions, whether boxing or football or tennis, and baseball insofar as the conduct of the sport is relevant to the criteria or considerations by which the Sherman Law becomes applicable to a 'trade or commerce'", Frankfurter wrote. "It can hardly be that this Court gave a preferred position to baseball because it is the great American sport. I do not suppose that the Court would treat the national anthem differently from other songs if the nature of a song became relevant to adjudication."[63]

Minton, conversely, believed that the Court should have held boxing equally beyond the reach of antitrust law. Accusing the majority of having misread Toolson, he wrote:[63]

When boxers travel from State to State, carrying their shorts and fancy dressing robes in a ditty bag in order to participate in a boxing bout, which is wholly intrastate, it is now held by this Court that the boxing bout becomes interstate commerce. What this Court held in the Federal Baseball case to be incident to the exhibition now becomes more important than the exhibition. This is as fine an example of the tail wagging the dog as can be conjured up.

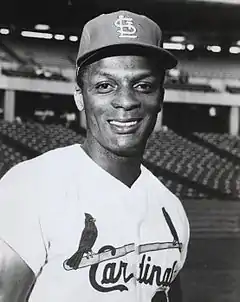

Curt Flood

Charles Curtis Flood was born on January 18, 1938, in Houston, Texas, the youngest of Laura and Herman Flood's six children. The family moved to Oakland, California, two years later in search of the naval jobs that had been created by the United States's pending entry into World War II.[64] Flood began playing baseball around the age of seven or eight, and he joined his first organized team in 1947, catching for Junior's Sweet Shop.[65] In addition to playing American Legion Baseball, Flood attended McClymonds High School with future MLB player Frank Robinson, who was two years his senior. Throughout his adolescence, Flood transitioned from catcher to shortstop and finally center fielder.[66] Outside of baseball, his primary passion was in the visual arts, inspired by his high school art teacher Jim Chambers.[67] Flood knew that he wanted a career in either art or baseball, but he had been warned by coach George Powles that his diminutive size and his race would impede his progression in professional baseball.[68]

On January 30, 1956, three days after graduating from high school, Bobby Mattick, a scout for the Cincinnati Reds, offered Flood a $4,000 contract to join the team.[69] Flood was assigned to the minor league High Point-Thomasville Hi-Toms, where he encountered segregation and racist chants from the fans.[70] He was successful on the field, however, batting .340 with 29 home runs and 128 runs scored, and he was promoted to the Reds as a September call-up.[71] Flood made his major league debut on September 9, pinch running for Smoky Burgess in a 6–5 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.[72]

Once the season ended, Flood met with Reds general manager Gabe Paul, who explained that while the team had been impressed by Flood's performance, they were not in a financial position to increase his salary, which would stay at $4,000 ($39,000 in modern dollars[33]) again for the 1957 season.[73] Flood realized after this meeting the gravity of the reserve system, later saying, "I could only play where they elected to send me. This was baseball law. It was beyond question or dispute. It was taken entirely for granted."[74] The Reds assigned Flood to the Dominican Winter League to teach him third base, which they hoped he would play in the future. When he returned, he was assigned to the Savannah Reds of the South Atlantic League.[75] Flood's batting average fell significantly in Savannah, which Paul used as a reason not to raise his salary for the 1958 season. Paul also informed Flood that he would have to report to the Venezuelan Winter League and learn how to play second base.[76]

On December 5, 1957,[77] the Reds traded Flood and Joe Taylor to the St. Louis Cardinals in exchange for Marty Kutyna, Ted Wieand, and Willard Schmidt,[78] a trade which came with a 25 percent raise.[79] The Cardinals' owner, Gussie Busch, was motivated to acquire more black baseball players to increase the team's local popularity, and he had failed to acquire Willie Mays and Ernie Banks.[80] Flood spent three weeks in the Cardinals' farm system before debuting with his new team on May 2, 1958, where he faced the team that traded him.[81] He did not become an everyday player in St. Louis until midway through the 1961 season, when manager Solly Hemus was fired and replaced by Johnny Keane.[82]

From 1965 to 1967, Flood had a reputation as an all-star defensive center fielder, setting an MLB record for playing 226 consecutive games without making an error in 555 chances.[83] Flood's salary increased throughout this period as well: he made $45,000 in 1966, significantly more than the average MLB player's $13,000 salary.[84] After making $50,000 in 1967, Flood came to offseason negotiations demanding that his salary be doubled for 1968. When general manager Bing Devine refused, Flood threatened to retire from baseball entirely, and the two parties settled on a $72,000 salary.[85] That season, Flood appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated, where he was deemed the best center fielder in baseball.[78]

The Cardinals faced the Detroit Tigers in the 1968 World Series. The matchup was fairly even, and both teams remained scoreless through the first six innings of Game 7. Both Norm Cash and Willie Horton singled for the Tigers in the seventh inning, leaving Cash in scoring position. Next up to bat, Jim Northrup hit a long fly ball to center field. Flood slipped on the wet outfield turf, his stumble causing the ball to miss his glove and roll towards the outfield wall. That error allowed both Cash and Horton to score, putting the Tigers up 2–0. Flood apologized to pitcher Bob Gibson after the inning, but Gibson insisted, "It was nobody's fault."[86] The Tigers won the game 4–1, defeating the Cardinals and becoming World Series champions.[87]

During offseason contract negotiations, Flood rejected the Cardinals' proposed salary of $77,500 ($573,000 in modern dollars[33]) for the 1969 season. He insisted on $90,000, telling Busch that number "is not $77,500 and is not $89,999".[88] Although he acquiesced, Busch was upset that the negotiations had turned sour at all, as he believed he had a good relationship with Flood.[89] Busch was the first to ask Keane to give Flood a regular playing opportunity in the outfield, he had provided Flood's family with financial assistance, and Flood had once painted Busch's portrait.[90]

Overall, the team's relationships with each other and with management suffered in 1969. The on-field camaraderie that Flood had previously praised seemed to have diminished,[91] while the players were unhappy with Busch after he accused them of being greedy for boycotting spring training in the name of higher wages.[92] Also during spring training, Flood had suffered an injury during an exhibition game against the New York Mets, and the sedatives he was provided by a team doctor caused him to sleep through the Cardinals' annual season ticketholder banquet. Flood was fined $250 for missing the banquet, at which point he began to publicly criticize the Cardinals' front office to local news media.[93] On the field, MLB had made several changes that were meant to increase hitting, including lowering the pitcher's mound and expanding the strike zone. While Flood batted .285 for the year, he was no longer one of the top 50 hitters in the league.[91]

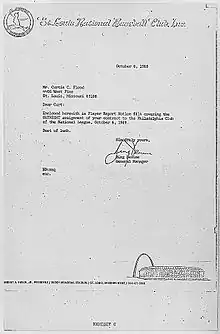

Early one morning in October 1969, a sportswriter notified Flood that he, Tim McCarver, Joe Hoerner, and Byron Browne had been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in exchange for Dick Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson.[94] Shortly afterwards, he received the official phone call from Jim Toomey,[94] an executive for the Cardinals that he later referred to as "a middle-echelon coffee drinker in the front office".[95][96] After hanging up the phone, Flood began to cry, and he spent the remainder of the day waiting for another call with more information.[97]

The next day, Flood, who had been preparing for a vacation in Copenhagen, received a one-sentence letter from Devine saying that he had been traded outright to the Phillies.[98] Flood responded by announcing his retirement from baseball and embarking on his previously scheduled vacation.[96] Devine did not immediately believe Flood, who had previously threatened to retire in order to improve his own salary.[99]

After returning from Copenhagen, Flood scheduled a meeting with Phillies general manager John Quinn, who attempted to convince him that the team was better than its reputation.[100] At the time, the Phillies were known for their lackluster treatment of their players, sending them on red-eye commercial propeller flights where other teams would charter private jets for away games.[101] Flood was particularly concerned about Philadelphia's reputation for mistreating its black players, as Allen had been vocal about the racism he experienced from management, fans, and the press during his time with the Phillies.[99] Flood was not active in the Black Power movement, but he was sympathetic to the cause,[102] and he remained sensitive to the racism and segregation that he had experienced earlier in his baseball career.[103]

Path to the Supreme Court

Initial meetings

After his meeting with Quinn, Flood contacted Allan H. Zerman, the attorney who had helped him set up his photography business in St. Louis, to ask for advice.[104] Zerman suggested that Flood sue, and so he contacted Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA).[105] In their first meeting, Miller explained to Flood and Zerman that Federal Baseball and Toolson had created a precedent that would make it difficult to eliminate the reserve clause, but that Gardella's case had given them an opening.[106] While Miller warned Flood that he would inevitably lose the court decision and his baseball career, he also provided Flood with attorney Arthur Goldberg, a former U.S. Supreme Court justice.[107] Miller and Goldberg had known each other from their time in the United Steelworkers labor union,[108] and Goldberg had written the majority opinion on several Supreme Court cases relating to antitrust, which Miller believed would help Flood's case.[109]

In December 1969, the MLBPA questioned Flood for two hours. Some team representatives, including Los Angeles Dodgers catcher Tom Haller, asked if Flood's case was primarily a race issue, to which Flood responded that his concerns about race were secondary to his belief that there should be a free market of players.[110] Other players worried that Flood was only threatening legal action as a ploy to increase his salary with the Phillies.[108] He assured the union that he was singularly opposed to the reserve clause, promised that he would not drop the case no matter what pressure he received from the owners, and offered to donate any damages he might be awarded to the union.[111] All 25 representatives voted to provide Flood with the funds needed to mount his lawsuit.[107] Despite the unanimous vote, Carl Yastrzemski sent a letter to Miller complaining that his voice had not been heard and fearing legal action would irreparably harm the relationship between owners and players.[112]

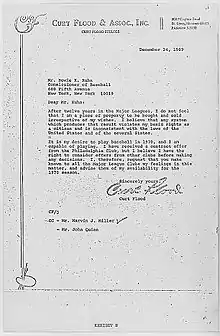

During this time, Paul A. Porter, one of MLB's top lawyers, met with the Players Association and denied any amendments to the reserve clause. When Jim Bouton asked the league's attorneys if they would consider terminating a player's reservation upon their 65th birthday, long after the player would have retired, Louis Carroll replied, "No, next thing you'll be asking for is a fifty-five limit."[113] Meanwhile, in a final effort to avoid legal action, Flood sent a letter to Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn on December 24 petitioning Kuhn to let him become a free agent. Kuhn responded that his contract remained under Philadelphia's control and could not be changed.[14] Shortly after the New Year, Flood appeared on Wide World of Sports for an interview with newscaster Howard Cosell.[114] Cosell asked Flood, "What's wrong with a guy making $90,000 being traded from one team to another? Those aren't exactly slave wages", to which Flood replied, "A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave."[115]

District Court

Flood filed a complaint in federal district court for the Southern District of New York in January 1970. He named Kuhn, the presidents of the NL and AL, and all 24 MLB team presidents as defendants. While Flood did not seriously believe he would be awarded the $1 million in damages that he requested, he was more concerned with having the reserve clause struck down.[116] The following day, Joe Cronin and Chub Feeney, the presidents of the AL and NL, respectively, issued a statement reiterating that the clause was "absolutely necessary", and that without it, "professional baseball would simply cease to exist".[117] Three of the five causes of action in Flood's suit related directly to the reserve system as an antitrust violation. The fourth suggested that the system was a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment, as it "subjects plaintiff to peonage and involuntary servitude".[118] The final cause of action suggested that the Cardinals and Yankees were engaged in additional antitrust violations unrelated to the reserve clause. The Cardinals, owned by Anheuser-Busch, sold only that brewery's products at Busch Stadium, while the Yankees, owned by CBS, only broadcast their games on that network.[119]

At the first hearing, held before Judge Dudley Baldwin Bonsal, the owners were granted an additional two weeks to prepare their reply.[120] Flood sought a preliminary injunction at a February hearing, which Judge Irving Ben Cooper rejected a month later.[121][122] The injunction was the only recourse Flood's attorneys had to block his trade to Philadelphia, making him either a free agent or reverting his rights back to the Cardinals,[123] and so in April, the Phillies placed Flood on the restricted list for failure to report.[121] Flood's attorneys chose not to appeal Cooper's ruling on the injunction, not wanting to delay the trial further.[124]

Flood's federal bench trial began in May.[125] Shortly beforehand, he received a call from Monte Irvin telling him that Kuhn was willing to give Flood a limited free agency where he would be allowed to negotiate a contract with any NL team. Flood rejected the offer, realizing that to accept it would damage his legal argument.[126] Goldberg, meanwhile, had announced his candidacy for Governor of New York earlier that year, and his campaign afforded him little time to prepare for the trial.[121]

Flood was the first to testify. He was nervous on the witness stand and struggled to recall his salaries and playing statistics from previous years, often using his own baseball card, provided by attorney Jay Tompkins, as a reference.[125] Flood said that he wanted to continue playing in St. Louis, where his photography and portrait businesses were located, but fundamentally wanted the option to accept the best deal that any team offered him.[127] When defense attorney Mark Hughes directly asked Flood if he wanted to abolish the reserve clause, as had been his position throughout, Flood misspoke and said he simply wanted it modified.[128] At the end of his testimony, Hughes asked Flood what he believed would happen if every MLB player became a free agent at the end of the season, to which Flood responded, "I think then every ballplayer would have a chance to really negotiate a contract just like in any other business."[129] Cooper asked Goldberg if he would like his client's response struck from the record, to which Goldberg replied, "No, I like that answer."[130]

.jpg.webp)

Miller was the next to testify, arguing to abolish the reserve clause.[125] He referred to it exclusively as the "reserve clause system", as the specific clause was no longer included in contracts but was a fundamental aspect of MLB, and he critiqued the fairness of such a system.[131] Flood and Miller were supported by former baseball players such as Jackie Robinson, who testified that without "some change in the reserve system, I can see nothing else but that the players go on strike".[125] Hank Greenburg, a former Detroit Tiger, recalled that he had been notified of his trade to the Pittsburgh Pirates by telegram,[132] and he testified that the "reserve clause should be eliminated entirely, thereby creating a new image for baseball".[125] The one MLB owner to testify in Flood's favor was Bill Veeck, who declared that every player "at least once in his career should be able to determine his own future and not be held in perpetuity".[133]

Defense witnesses included Kuhn, Feeney, Pro Football Commissioner Pete Rozelle, and several MLB executives.[133] One day of the trial consisted entirely of the testimony of Robert R. Nathan, an economic consultant who said that the reserve system did stifle competition, but that the alternative would lead to smaller-market teams like the Milwaukee Braves being choked out by teams in large markets like Philadelphia and New York.[134] This sentiment was later echoed by team owners including Bob Reynolds of the Los Angeles Angels, Frank Dale of the Cincinnati Reds, John McHale of the Montreal Expos, and Ewing Kauffman of the Kansas City Royals, all of whom insisted that the reserve system was necessary to preserve the "economic health" of their respective franchises.[135] On the sixth day of the trial, Kuhn argued in favor of the historical precedents set by the reserve clause and Supreme Court.[136] He was careful not to criticize Flood personally, instead attacking the MLBPA as acting in bad faith and not committing to "realistic negotiations" with the owners.[137]

The trial ended in June, and both sides were given a month to submit post-trial briefs to Cooper.[138] By this time, Flood appeared to have lost interest in the proceedings. He had been absent from Veeck's testimony, having gone to Shea Stadium to watch Gibson pitch against the New York Mets.[133] Flood's team produced an 88-page document detailing the inconsistencies on baseball's position: while baseball may have been exempted from federal antitrust laws under Federal Baseball and Toolson, it was still subject to state antitrust laws. The 133-page brief from MLB's attorneys, meanwhile, suggested that Flood was acting as a pawn of the Players Association.[139] In August, Cooper delivered a 47-page opinion in which he upheld the reserve clause under the precedent set by Toolson.[133] He also rejected the Thirteenth Amendment cause of action, saying that Flood was under no obligation to actually play for Philadelphia: while retiring from baseball would bring him financial harm, that option was still open.[140][141]

Flood had also argued that if federal antitrust state law did not reach baseball, then equivalent state laws had to. Cooper disagreed, noting that in 1966 the Wisconsin Supreme Court had found that idea "unrealistic" when it ruled against that state's attempt to use those laws to prevent the Milwaukee Braves' move to Atlanta,.[142] Closer to home, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, whose decisions are binding precedent on the Southern District, had likewise in 1970 rejected the same argument made by two AL umpires who alleged they had been fired in retaliation for their union organizing efforts.[143] Noting that the reserve clause had not been at issue in that case, Cooper concluded that "[the] application of various and diverse state laws here would seriously interfere with league play and the operation of organized baseball.[144]

Court of Appeals

Shortly after Cooper rendered his decision, Flood appealed it to the Second Circuit.[145] In April 1971, a unanimous opinion by Judge Sterry R. Waterman upheld Cooper's decision under Federal Baseball and all subsequent rulings on the principle of stare decisis.[146] It also cited the 1957 Supreme Court ruling in Radovich v. National Football League[147] to suggest that while baseball's exemption from the antitrust laws under which other sports leagues fell was "unrealistic", "inconsistent", and "illogical", it was still the Supreme Court's prerogative to overrule it and Toolson.[148] Judge Leonard P. Moore wrote a concurring opinion tracing in greater detail the history of baseball and its antitrust exemption, which he did not believe the Supreme Court would revoke. He concluded that, aside from the Chicago Black Sox scandal baseball had managed to grow and retain the public's interest remarkably well without judicial intervention. "[I] would limit the participation of the courts in the conduct of baseball's affairs to the throwing out by the Chief Justice (in the absence of the President) of the first ball of the baseball season."[149]

In July, Flood's attorneys filed a certiorari petition with the clerk of the US Supreme Court, the first step towards asking the Court to hear the case.[150] MLB's attorneys submitted their response to the writ on August 23, and the Court agreed to hear the case on October 19, 1971.[151]

In his absence with the Phillies as the case moved through the courts, Flood's rights returned to the Cardinals, who negotiated another trade with Philadelphia. The Phillies received two minor league prospects and placed Flood on their voluntary retirement list, which meant that he did not count against their 40-man roster, but if he chose to return to baseball, he could only play for Philadelphia.[152] The Washington Senators acquired Flood's rights from Philadelphia partway through the 1971 season, and Flood accepted a one-year, $110,000 contract to recoup the financial losses that came with missing the 1970 season.[145] Senators owner Bob Short promised Flood that accepting a deal with the team would not damage his court case, as he could argue that he had already accrued damages from missing the previous season.[153] Flood played only 13 games with the Senators, quitting on April 28 after performing poorly, and moved to Madrid to distance himself from baseball and the stress of his court case.[154]

Before the Court

Once the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, both sides submitted briefs. Flood's attorneys received a two-week extension from Justice Thurgood Marshall and submitted theirs in December 1971, while MLB responded at the end of January 1972.[151] Goldberg's brief had eliminated the Thirteenth Amendment concerns entirely and focused on how the reserve system had become "drastically more restrictive" since its introduction and previous litigation.[155] Paul Porter and Lou Hoynes responded to Goldberg's antitrust assertions by arguing that Flood's case was a labor dispute that should have been settled in a collective bargaining agreement between league and union, not in court.[156]

Oral arguments

Oral arguments in Flood v. Kuhn were heard on March 20, with both sides allowed to speak for 30 minutes.[156] Goldberg spoke on Flood's behalf first, speaking of the unfairness of the reserve clause and how it had in 1965 been made worse through its extension to rookie players signing their first contracts to play in the minor leagues. He told Justice William J. Brennan Jr. that Flood would oppose the reserve clause even if it had been the result of collective bargaining. Justice Byron White asked if playing baseball was not covered under the labor exemption to antitrust law; Goldberg noted that Kuhn himself had described baseball as entertainment, which the Court had previously ruled was interstate commerce. "Every commentator has said it's an anomaly in the law to adhere to Federal Baseball and Toolson as wrongly decided", Goldberg concluded, commenting that if the steelworkers union, a former client, had agreed to similar terms with any employers binding a member or members to them for his entire working life, that contractual provision would clearly be seen as a per se violation of the law.[157]

Paul A. Porter came next, arguing for Kuhn and MLB in rebuttal that baseball was unique, even compared to other sports, in the antitrust context because of the portion of its revenues invested in player development through their extensive farm systems. Louis Hoynes, counsel for the NL, argued MLB's case. He placed great emphasis on the MLBPA, which he said "has in fact controlled this litigation from beginning to end", to suggest that the real goal of the lawsuit was to make far more sweeping changes to the business aspect of baseball, and that these matters were far better addressed at the bargaining table.[157]

Deliberations

Following oral arguments, the Court took an unofficial voice vote in order of seniority.[158] Chief Justice Warren E. Burger began by admitting that "Toolson is probably wrong", but he did not say whether he believed the lower courts' rulings should be reversed.[159] William O. Douglas voted to reverse the previous decisions and wanted to remand the case to district court for a new trial.[158] Brennan agreed that Toolson should be overturned, but he also believed that Flood was primarily a labor dispute that should remanded for a new trial that did not focus on antitrust concerns.[160] Justice Potter Stewart voted to uphold the lower courts' rulings under Congress's explicit decision to exempt baseball from antitrust laws, and his position was joined by Marshall and Justice Byron White. Justice Harry Blackmun also saw the case as a labor dispute and tentatively voted to affirm.[161] Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. recused himself, as he owned stock in Anheuser-Busch.[162] While waiting for confirmation that the Cardinals were a subsidiary of the company,[163] he stated in a voice vote that he believed the lower courts' rulings should be reversed, as it made "no sense" that baseball received different treatment in antitrust cases than other sports such as football.[161] Justice William Rehnquist, the last to vote, affirmed the decision of the lower courts.[161]

Without Powell, the court remained at a 4–4 deadlock until Burger changed his vote in favor of MLB.[162] On June 19, 1972, the Court delivered its decision,[156] with both parties notified by telegram that the lower courts' rulings had been upheld by a 5–3 margin. Blackmun, Stewart, Rehnquist, Burger, and White formed the majority, with Douglas, Marshall, and Brennan dissenting.[164] Had the 4–4 tie remained, the decision of the lower courts would have been affirmed, but the Court would not have published any opinions.[165] None of the opinions specifically addressed the reserve clause; all instead focused on baseball's antitrust exemption.[166]

Decision

Blackmun's opinion

Stewart had been asked to select the writer for the majority, a duty which he imparted on Blackmun, a noted baseball fan and the only member of the majority whose opinions seemed to have wavered on the case.[167] Stewart told Blackmun to "do it very briefly ... Write a per curiam and we'll get rid of it".[168] Blackmun's draft was over 20 pages long and divided into five sections.[162] Rather than rewriting the majority opinion after seeing a draft of the dissenting opinions, as is custom, Blackmun's only major alteration between his first and second drafts was in expanding his list of notable baseball players from 74 to 88.[169]

Section I of Blackmun's opinion[170] has been described as an "ode to baseball".[162] The first three paragraphs detail the history of the sport, beginning with the first organized game in 1846 and continuing through the formation of the MLBPA in 1966. This is followed by a list of 88 players he considered great.[171] Some of them were beyond an average fan's knowledge, including Heinie Groh, Dan Brouthers, and Chief Bender.[172] While Blackmun never explicitly cited the origins of his list, he kept a copy of the Encyclopedia of Baseball on his chambers desk, and many of the players he lists are found in The Glory of Their Times by Lawrence Ritter.[173] It is rumored that Marshall called Blackmun after seeing the original draft of the opinion to ask why no black players were included. Blackmun responded that there were no great black players in the golden age of baseball, but he ultimately included Jackie Robinson, Satchel Page, and Roy Campanella.[174] Blackmun denied this rumor, saying that Campanella had been on his original list, and he later said that the one player he had forgotten was Mel Ott.[172] Section I concludes with various baseball arcana, including Ring Lardner's reference to the "World Serious", a line from the poem "Baseball's Sad Lexicon", and quotes from George Bernard Shaw, Franklin Pierce Adams, and "Casey at the Bat".[175]

The remainder of Blackmun's opinion proceeds as standard. Section II, titled "The Petitioner", outlines Flood's career, salary history, and the trade that had provided the impetus for the lawsuit.[176] Section III, titled "The Present Litigation", summarized Flood's lawsuit.[177][162] Section IV discusses the legal precedents set by Federal Baseball and Toolson.[178][179] Finally, Section V presents the rationale of the court, with eight specific findings concluding that baseball, while a type of interstate commerce, is also a unique industry exempt from antitrust laws.[180][181] Blackmun's opinion focuses primarily on stare decisis, conceding that while the decision in Federal Baseball to exempt the sport from antitrust status was an "anomaly", its precedent was sufficient that changes could only be made through Congress.[182][183]

Concurrences

White and Burger both wrote short concurring opinions, noting that they exempted Section I. White, a former football star at the University of Colorado, believed that Blackmun's rambling ode to baseball was demeaning to the Court.[184] Burger, meanwhile, showed his sympathy for Douglas's dissent but argued that Toolson had been precedent for so long that he could not support Flood and the upheaval that would cause.[167] Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong's 1979 Supreme Court biography, The Brethren, claimed that many justices were embarrassed by Section I's overt sentimentality.[153]

Dissenting opinions

Two dissenting opinions were provided by the three remaining justices. One was written by Douglas, with Brennan concurring.[185] Douglas directly critiqued the assertion that baseball had remained the same in the 50 years following the decision in Federal Baseball, and that the sport had become "big business that is packaged with beer, with broadcasting, and with other industries".[185] He particularly rebuked Blackmun's assurance that Congress would handle any alterations to the antitrust exemption, writing that they had not done so to this point.[186] Douglas was the only member of the Court who had also been on the bench for the Toolson decision, in which he had voted in favor of upholding Federal Baseball. He used his dissent in Flood to express his regret for that decision, writing that "the unbroken silence of Congress should not prevent us from correcting our own mistakes".[184]

Marshall wrote the other dissenting opinion, again with Brennan concurring.[185] Marshall's dissent was a reversal of his voice vote, in which he had implied that he would affirm the appellate ruling on the basis of Congress's antitrust exemption for baseball. Marshall focused his dissent on the issue of Flood as an individual, whose rights he believed were impinged upon by a system that held players in perpetuity.[187] He used the opinion to attack the precedents set by Federal Baseball and Toolson, arguing that he would have overruled both and reversed the appellate court's decision.[184] He explicitly invoked Radovich and United States v. International Boxing Club of New York, Inc., two cases in which antitrust exemptions had not been applied to other sports, as cause for the Supreme Court to reverse their rulings on baseball to consistently apply antitrust legislation across all professional athletics.[188] Marshall did clarify, however, that he believed the particulars of Flood's case belonged at the level of the district courts as a labor dispute, where that lower court could investigate whether the antitrust violations practiced by MLB circumvented the league's collective bargaining agreement with the Players Association.[166]

Aftermath

The ruling in Flood v. Kuhn came as a surprise to many sportswriters and scholars who were following the case. Harold Spaeth, a political scientist at Michigan State University, had predicted that Flood would prevail either unanimously or with Rehnquist as the sole dissent. Sportswriter Tom Dowling, who had been present for the oral arguments, believed that the case would be remanded, Flood awarded damages, and Kuhn would have to create a free agency system with the players.[189] Despite the owners' legal victory, popular opinion had turned against the league, with some polls showing baseball fans in favor of Flood by an 8:1 margin.[190]

At no point after the ruling did Flood return to professional baseball. He lived in Spain for a period of four years, where he owned a bar and worked as a carpet layer.[166] Upon his return to the United States, he spent time as an announcer for his hometown Oakland Athletics, as a Little League Baseball coach, and as commissioner of a senior baseball league.[191] The Gold Glove Award which he had won for the 1969 season but had not formally received due to his legal dispute was presented to him in 1994.[191] Flood was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1996, and he died of pneumonia at a Los Angeles hospital on January 20, 1997.[192] The year after his death, he was posthumously elected to the Baseball Reliquary, which honors players both for their on-field statistics and for their off-field character.[193]

The breakdown of Busch's relationship with Flood was compounded by the Cardinals' decision to terminate Harry Caray's announcer contract. These upheavals left Busch emotionally disturbed, with his son Adolphus Busch IV later writing, "[s]omething had occurred that made him question whether he should stay on as CEO of the company or retire".[194] In 1975, his other son, August Busch III, began a boardroom coup to oust his increasingly erratic father out of Anheuser-Busch.[195] While August took over the brewing industry, he allowed Gussie to remain president of the Cardinals as long as he accepted his son's usurpation and publicly announced that he was retiring of his own accord.[196] Busch died of pneumonia and congestive heart failure on September 29, 1989.[197]

Subsequent developments

Seitz decision

Their loss in Flood signalled to the MLBPA that any serious revisions to the league's operations could not go through the courts.[198] The original collective bargaining agreement between the league and Players Association had created an arbitration system through which labor disputes were handled.[199] Miller used arbitration to the players' advantage, encouraging them not to sign contracts and to take their salary disputes to this new third party.[200] MLB's first official free agent was Catfish Hunter, who in 1974 took the Oakland Athletics to arbitration for a straightforward breach of contract. Arbitrator Peter Seitz declared Hunter's contract with the Athletics to be void and that Hunter was free to sign with whatever team he wished. His subsequent $5.5 million contract with the New York Yankees was at the time the largest of any major league player.[201]

Also in 1974, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith, who had led the NL in wins that season, asked owner Walter O'Malley both for a raise and for a no-trade clause added to his 1975 contract. While O'Malley granted Messersmith the raise, he could not offer a no-trade contract, arguing that it was against league rules.[202] Messersmith refused to sign his contract until the clause was added, and the Dodgers renewed his previous contract without his consent.[203] When O'Malley refused to include a no-trade clause again at the end of the 1975 season, Messersmith met with Miller to discuss future options.[204] Miller connected him with Dave McNally, who had retired partway through the previous season after he was traded from the Baltimore Orioles to the Montreal Expos.[204] If McNally ever chose to unretire from baseball, the reserve system meant that he would have to play for the Expos. McNally, a strong union supporter, joined Messersmith to ensure the case went to arbitration rather than letting the Dodgers negotiate independently.[205]

In October 1975, the MLBPA filed two grievances on behalf of Messersmith and McNally, arguing that their contracts with the Dodgers and Expos had expired after the 1975 season, leaving both players essentially free agents.[206] The central argument around Messersmith's case regarded the Uniform Player's Contract of the Basic Agreement, which stated that "the Club shall have the right ... to renew his contract for the period of one year on the same terms".[207] Messersmith understood the contract to mean that the Dodgers had the right to extend his contract unilaterally for the 1975 season, but now that the season had passed, he was no longer under contract with the team. The Dodgers front office argued that renewing Messersmith's contract also renewed the one-year option, and that they could continue to extend his contract in perpetuity.[208]

On December 23, 1975, Seitz ruled in favor of the two pitchers that the Basic Argument only allowed unilateral extensions for a period of one year. Moments after issuing his ruling, the owners fired him as an arbitrator.[209] Seitz's decision was based on the question of whether the reserve clause extended to players whose contracts had expired. Rule 4-A(a) suggested that reservations only applied to players under active contract, while Major League Rule 3(g) prohibited opposing owners from approaching reserved players regardless of their contract status.[210] Seitz rested his decision on the Cincinnati Peace Compact that had united the National and American Leagues in 1903, which applied the reserve clause only to players under active contract.[211]

Seitz at no point addressed the antitrust exemption in his ruling, focusing his decision on the collective bargaining agreement. The Second Basic Agreement of 1970 included in Article XIV that, "Regardless of any provision herein, this Agreement does not deal with the reserve system."[212] Because the collective bargaining agreement did not directly deal with the system, any challenges to it were allowed to pass through arbitration.[213] After Seitz's ruling, the owners challenged his decision in the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri before John Watkins Oliver. Oliver cited a series of Supreme Court cases known as the Steelworkers Trilogy, which limited the power of the courts to overrule an independent arbitrator's decision.[214] Seitz and Oliver's decision was upheld again by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, and the owners decided against taking their case to the Supreme Court.[215]

1976 collective bargaining agreement

Kuhn did not consider the Flood decision to be a victory for MLB's ownership, as it made the reserve clause a target for future collective bargaining negotiations.[216] The MLB collective bargaining agreement made its first amendment to the reserve system after the 1973 Major League Baseball lockout. The "Curt Flood rule" provided that any player with 10 years of major league service, five of which had been with their current team, could veto a proposed trade.[217] This collective bargaining agreement expired on December 31, 1975, which required the owners and players to create a new Basic Agreement.[215] After clashing over many aspects of this agreement, the owners instituted another lockout in March 1976. A new agreement did not come to fruition until July 12, 1976.[218]

Under the 1976 agreement, players who had signed a contract with their team before August 9, 1976, would become free agents at the end of that season. The club was allowed to extend their contract for one year, at which point the player would enter free agency in 1977.[219] All players who signed contracts after that date would automatically reach free agency after six years of major league service. Any player with five seasons of service, meanwhile, could demand a trade of their owner and provide a list of teams to whom he did not wish to be traded. If that player was not moved to an agreeable team by March 15, he would also become a free agent.[218]

Legislative action

While Congress responded to Flood by introducing two bills that would have repealed baseball's antitrust exemption, the bills were unpopular among legislators, and the only immediate legal effect was a 1973 bill expanding the broadcast of sold-out regular-season professional sporting events.[220] Their next move was to create the Select Committee on Professional Sports in May 1976, which was presided over by California Democrat B. F. Sisk.[221] The Sisk Committee explored several contemporary issues in professional sports, including baseball's antitrust exemption. The league argued that the exemption was necessary to maintain a competitive balance among teams, and the Committee was also tempted to uphold the exemption through veiled promises that new MLB franchises would expand into their districts. While the Sisk Committee ultimately ruled that there was no adequate justification for baseball's antitrust exemption and recommended that it be lifted accordingly, no legislation was ever brought before Congress to enact such a reversal.[222] The committee also recommended a successor committee be established on sports antitrust law, but the committee never convened. The most that came to fruition was a study on the matter which was prepared and published in 1981.[223] Representative Gillis Long attempted to pass a bill that would strip MLB of its "favorite son treatment", which he announced in a hearing with Larry O'Brien, the Commissioner of the NBA, but the bill died in committee.[223]

In January 1995, a bill that would have eliminated baseball's antitrust exemption was introduced to the Senate, where it died in committee soon after the resolution of the 1994–95 MLB strike. Orrin Hatch reintroduced the bill the day after Flood's death as the "Curt Flood Act of 1997". The purpose of the bill was to "clarify that major league baseball players and owners have the same legal rights, and the same restrictions, under the antitrust laws as the players and owners in other professional sports leagues".[224] The bill was voted out of committee that October and was approved by Congress the following January. President Bill Clinton signed the Curt Flood Act of 1998 into law on October 28, 1998.[225] While the relationships between players and ownership now fell under federal antitrust protections, other aspects of professional baseball, including franchise expansion, relocation, ownership, and ownership transfers, as well as "the marketing and sales of the entertainment product", remained exempt.[226]

Analysis

Blackmun's opinion was immediately unpopular among sportswriters such as Arthur Daley of The New York Times, who decried it as revealing "a total lack of logic".[153] It has retrospectively been criticized by legal scholars as well, who are unhappy both with the rigid application of stare decisis and with the continued exemptions received by baseball for its reputation as the "national pastime".[227]

William Eskridge has referred to Flood v. Kuhn and the other cases in the "baseball trilogy" as "the most frequently criticized example of excessively strict stare decisis" among legal scholars.[228] For Kevin D. McDonald, the case is both "indefensible as a matter of fact or policy" and "an embarrassment to the Court".[229] Roger Ian Abrams wrote that the Court had "boxed itself in" by insisting on upholding Federal Baseball in Flood despite acknowledging the different circumstances regarding those two cases.[230] David Snyder went so far as to say that in arguing Flood, "the Supreme Court had completely lost sight of the factual, legal and conceptual underpinnings of Federal Baseball".[231] Morgen Sullivan notes that there is a contradiction in the Flood ruling, as the opinion explicitly states that baseball's antitrust exemption is limited to the reserve system, but ends by quoting a line in Toolson that expands the exemption to "the business of baseball".[232] Mitchell Nathanson, meanwhile, states that the Supreme Court "finally acknowledged the absurdity of Holmes' contention ... but then inserted its own absurdity when it concluded that the fact that baseball is engaged in interstate commerce was nevertheless irrelevant".[233]

Of particular contention to scholars is the Court's assertion that Congress would undo baseball's antitrust exemption. Citing their previous inaction, Abrams argues that Congress had sufficiently demonstrated its refusal to act, leaving the matter to the Courts.[234] William Basil Tsimpris has contrasted the application of stare decisis in Flood with the Court's ruling in Helvering v. Hallock, in which it was stated that Congress was unlikely to take action on a precedent, giving the Court the burden of self-correction.[235] For McDonald, the decision to leave baseball's antitrust status to Congress was a poor interpretation of Federal Baseball, as Holmes never specified that legislation was the only pathway to undo his ruling.[40]

In attempting to understand why MLB repeatedly enjoyed antitrust exemptions not afforded to other sports, scholars have largely targeted baseball's romantic reputation in American culture.[236] Abrams wrote that Blackmun "may have confused the business of baseball with the glorious game of baseball, thus explaining the sentimentality of Section I,[182] which has been criticized as "rambling and syrupy", "juvenile", and even "bizarre".[237] Savanna Nolan observed that even "the more serious elements of the opinion have a touch of ridiculousness" due to Blackmun's feelings towards the sport.[238] Stephen Ross takes a slightly more positive view, justifying Section I as a means "to establish the unique role that baseball plays in American culture", but nevertheless rationalizes that romantic picture influenced the Court's decision to exempt baseball from other business rules.[239]

See also

- 1972 in baseball

- Baseball law

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Burger Court

- Bosman ruling – 1995 European Court of Justice decision that allowed unrestricted free agency in the European Union

Notes

- Not New York's highest court

- Although the decision did not explicitly exempt baseball from antitrust regulation, saying only that its nature did not fall under the Sherman Act, Federal Baseball has become known as "baseball's antitrust exemption".[39] The understanding that baseball was exempt from the antitrust laws regarding other sports did not come into effect until the 1950s, when sports such as boxing and football lost cases that would have given them the same protections.[40]

References

- Thornton 2012, p. 158.

- Abrams 1998, pp. 45–46.

- Duquette 1999, p. 5.

- Goldman 2008, p. 32.

- Abrams 1998, p. 47.

- Duquette 1999, p. 6.

- Duquette 1999, p. 8.

- Banner 2013, p. 5.

- Abrams 1998, p. 18.

- Banner 2013, p. 9.

- Abrams 1998, p. 48.

- Banner 2013, pp. 9–10.

- Abrams 1998, p. 20.

- Thornton 2012, p. 166.

- Lowenfish 2010, pp. 35–36.

- Abrams 1998, p. 19.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 41.

- Goldman 2008, p. 34.

- Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ward, 24 Abb. N. Cas. 393, 414 (Sup.Ct.N.Y. New York 1890).

- Lowenfish 2010, pp. 47–50.

- Banner 2013, p. 20.

- Philadelphia Ball Club, Ltd. v. Lajoie, 51 A. 973 (Pa. 1902).

- Lumley v Wagner, 64 ER 1209 (C.Ch 1852).

- Goldman 2008, pp. 37–38.

- Abrams 1998, pp. 48–49.

- Abrams 1998, p. 53.

- Abrams 1998, p. 54.

- Lowenfish 2010, pp. 78–79.

- Lowenfish 2010, pp. 81–82.

- Abrams 1998, p. 55.

- Kutcher 2014, p. 241.

- Abrams 1998, p. 56.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- Goldman 2008, p. 45.

- Abrams 1998, p. 57.

- Abrams 1998, p. 58.

- Tehranian 2018, p. 961.

- Goldman 2008, p. 46.

- Banner 2013, p. 88.

- McDonald 2005, p. 9.

- Hart v. B.F. Keith Vaudeville Exchange, 262 U.S. 271 (1923).

- Banner 2013, p. 97.

- Duquette 1999, p. 45.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 161.

- Banner 2013, p. 98.

- Banner 2013, p. 99.

- Duquette 1999, p. 46.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 168.

- Duquette 1999, pp. 45–47.

- Abrams 1998, p. 61.

- Duquette 1999, p. 48.

- Kutcher 2014, p. 242.

- Abrams 1998, p. 60.

- Thornton 2012, p. 159.

- Banner 2013, p. 119.

- Toolson v. New York Yankees, 346 U.S. 356 (1953).

- Abrams 1998, pp. 60–61.

- Toolson, 357–365

- United States v. Shuster, 348 U.S. 222 (1955).

- United States v. International Boxing Club of New York, Inc., 348 U.S. 236 (1955).

- Shuster, 229–231

- International Boxing Club, 240–243

- International Boxing Club, 248–251

- Goldman 2008, p. 15.

- Belth 2006, pp. 11–12.

- Belth 2006, p. 21.

- Weiss 2007, p. 20.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 16–17.

- Weiss 2007, p. 24.

- Belth 2006, p. 33.

- Belth 2006, p. 35.

- Belth 2006, p. 36.

- Belth 2006, pp. 37–38.

- Goldman 2008, p. 17.

- Weiss 2007, pp. 42–43.

- Weiss 2007, p. 45.

- Weiss 2007, p. 47.

- Thornton 2012, p. 162.

- Belth 2006, p. 43.

- Goldman 2008, p. 19.

- Goldman 2008, p. 21.

- Belth 2006, p. 63.

- Snyder 2006, p. 5.

- Belth 2006, p. 98.

- Belth 2006, p. 120.

- Belth 2006, pp. 130–131.

- Belth 2006, p. 131.

- Knoedelseder 2012, p. 110.

- Knoedelseder 2012, pp. 110–111.

- Weiss 2007, p. 119.

- Goldman 2008, p. 1.

- Knoedelseder 2012, pp. 109–111.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 1–2.

- Snyder 2006, p. 1.

- Knoedelseder 2012, p. 111.

- Thornton 2012, p. 163.

- Weiss 2007, p. 135.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 2–3.

- Belth 2006, p. 143.

- Goldman 2008, p. 3.

- Snyder 2006, p. 13.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 208.

- Thornton 2012, pp. 159–161.

- Snyder 2006, pp. 14–15.

- Snyder 2006, pp. 15–16.

- Belth 2006, pp. 146–147.

- Thornton 2012, p. 164.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 209.

- Belth 2006, p. 155.

- Thornton 2012, p. 165.

- Goldman 2008, p. 4.

- Goldman 2008, p. 5.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 210.

- Snyder 2006, p. 103.

- Knoedelseder 2012, p. 113.

- Thornton 2012, p. 167.

- Belth 2006, p. 160.

- Goldman 2008, p. 10.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 10–11.

- Goldman 2008, p. 11.

- Thornton 2012, p. 168.

- Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F.Supp 793 (S.D.N.Y. 1970).

- Snyder 2006, p. 126.

- Goldman 2008, p. 13.

- Thornton 2012, p. 169.

- Lowenfish 2010, pp. 210–211.

- Goldman 2008, p. 73.

- Belth 2006, p. 168.

- Belth 2006, pp. 168–169.

- Belth 2006, p. 169.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 73–74.

- Goldman 2008, p. 76.

- Thornton 2012, p. 170.

- Goldman 2008, p. 77.

- Goldman 2008, p. 81.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 79–80.

- Goldman 2008, p. 80.

- Belth 2006, p. 171.

- Snyder 2006, p. 191.

- Goldman 2008, p. 83.

- Flood v. Kuhn, 316 F.Supp 271 (S.D.N.Y. 1970)., hereafter Flood I

- State v. Milwaukee Braves, 31 Wisc. 2d 699, 730 (Wisc. 1966) ("We deem it unrealistic to interpret these decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States plus the silence of Congress as creating a mere vacuum in national policy, leaving the states free to regulate the membership of the baseball leagues").

- Salerno v. American League of Professional Baseball Clubs, 429 F.2d 1003, 1005 (2nd Cir. 1970) ("[T]he ground upon which Toolson rested was that Congress had no intention to bring baseball within the antitrust laws, not that baseball's activities did not sufficiently affect interstate commerce.").

- Flood I, at 280

- Thornton 2012, p. 171.

- Flood v. Kuhn, 443 F.2d 264 (2nd Cir. 1971)., hereafter Flood II

- Radovich v. National Football League, 352 U.S. 445 (1957).

- Goldman 2008, p. 96.

- Flood II, 268–273

- Goldman 2008, p. 102.

- Goldman 2008, p. 104.

- Goldman 2008, p. 91.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 213.

- Thornton 2012, pp. 171–172.

- Goldman 2008, p. 105.

- Thornton 2012, p. 172.

- "Flood v. Kuhn Oral Argument - March 20, 1972". Oyez Project. March 20, 1972. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- Goldman 2008, p. 112.

- Banner 2013, p. 205.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 112–113.

- Goldman 2008, p. 113.

- Thornton 2012, p. 173.

- Snyder 2006, p. 286.

- Goldman 2008, p. 114.

- Banner 2013, p. 212.

- Thornton 2012, p. 176.

- Crepeau 2007, p. 187.

- Banner 2013, p. 207.

- Banner 2013, pp. 210–211.

- Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258, 260–264 (1972)., hereafter Flood III

- Snyder 2006, p. 294.

- Goldman 2008, p. 115.

- Abrams 2007, pp. 186–191.

- Abrams 1998, p. 66.

- Snyder 2006, p. 295.

- Flood III, 264–66

- Flood III, 266–69

- Flood III, 269–82

- Thornton 2012, pp. 173–174.

- Thornton 2012, p. 174.

- Flood III, 282–85

- Abrams 1998, p. 67.

- Flood III, at 284

- Thornton 2012, p. 175.

- Goldman 2008, p. 117.

- Snyder 2006, p. 298.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 117–118.

- Tsimpris 2004, pp. 78–79.

- Goldman 2008, p. 120.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 214.

- Thornton 2012, p. 177.

- Goldman 2008, p. 138.

- Goldman 2008, p. 139.

- Knoedelseder 2012, pp. 111–113.

- Knoedelseder 2012, p. 135.

- Knoedelseder 2012, p. 137.

- Knoedelseder 2012, p. 249.

- Tsimpris 2004, p. 79.

- Abrams 1998, p. 119.

- Banner 2013, p. 221.

- Thornton 2012, p. 179.

- Thornton 2012, p. 180.

- Thornton 2012, pp. 180–181.

- Thornton 2012, p. 181.

- Abrams 1998, p. 124.

- Thornton 2012, pp. 182–183.

- Abrams 1998, p. 118.

- Abrams 1998, pp. 118–119.

- Thornton 2012, pp. 183–185.

- Abrams 1998, pp. 125–126.

- Abrams 1998, p. 126.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 211.

- Abrams 1998, p. 125.

- Thornton 2012, pp. 188–189.

- Thornton 2012, p. 189.

- Crepeau 2007, p. 189.

- Lowenfish 2010, p. 217.

- Thornton 2012, p. 190.

- Duquette 1999, p. 70.

- Martin 1976, p. 280.

- Duquette 1999, pp. 70–71.

- Duquette 1999, p. 71.

- Duquette 1999, p. 72.

- Goldman 2008, p. 133.

- Goldman 2008, pp. 134–135.

- Goldman 2008, p. 134.

- Goldman 2008, p. 124.

- Eskridge 1988, p. 1380.

- McDonald 2005, p. 10.

- Abrams 1998, pp. 68–69.

- Snyder 2008, p. 199.

- Sullivan 1999, p. 1275.

- Nathanson 2006, p. 79.

- Abrams 1998, p. 68.

- Tsimpris 2004, p. 75.

- Tehranian 2018, pp. 963–964.

- Tehranian 2018, p. 957.

- Nolan 2020, p. 384.

- Ross 1994, p. 174.

Works cited

- Abrams, Roger I. (1998). Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-599-2.

- Roger I. Abrams, Blackmun's List, 6 Virginia Sports and Entertainment Law Journal 181-208 (2007)

- Banner, Stuart (2013). The Baseball Trust: A History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993029-6.

- Belth, Alex (2006). Stepping Up: The Story of Curt Flood and His Fight for Baseball Players' Rights. New York, NY: Persea Books. ISBN 0-89255-321-9.

- Crepeau, Richard (2007). "The Flood Case". Journal of Sport History. 34 (2): 183–191. JSTOR 43610015.

- Duquette, Jerold J. (1999). Regulating the National Pastime: Baseball and Antitrust. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96535-X.

- William N. Eskridge Jr., Overruling Statutory Precedents, 76 Georgetown Law Review 1361–1440 (1988)

- Goldman, Robert M. (2008). One Man Out: Curt Flood versus Baseball. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1603-9.

- Knoedelseder, William (2012). Bitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America's Kings of Beer. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-200927-2.

- D. Logan Kutcher, Overcoming an 'Aberration': San Jose Challenges Major League Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption, 40 The Journal of Corporation Law 233–258 (2014)

- Lowenfish, Lee (2010). The Imperfect Diamond: A History of Baseball's Labor Wars. Lincoln, NB: Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-3360-7.

- Philip L. Martin, The Aftermath of Flood v. Kuhn: Professional Baseball's Exemption from Antitrust Regulation, 3 Western State University Law Review 262–283 (1976)

- Kevin D. McDonald, There's No Tying in Baseball: On Illinois Tool and the Presumption of Market Power in Patent Tying Cases, 5 The Antitrust Source 1–20 (2005)

- Nathanson, Mitchell (2006). "Gatekeepers of America: Ownership's Never-ending Quest for Control of the Baseball Creed". NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture. 15 (1): 68–87. doi:10.1353/nin.2006.0050.

- Nolan, Savanna L. (2020). "Inside Baseball: Justice Blackmun and the Summer of '72". Green Bag Almanac & Reader. 10 (2): 383–393.

- Stephen F. Ross, Reconsidering Flood v. Kuhn, 12 U. MIA Ent. & Sports L. Rev. 169 (1994)

- Snyder, Brad (2006). A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood's Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports. New York, NY: Viking. ISBN 0-670-03794-X.

- David L. Snyder, Anatomy of an Aberration: An Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball through Flood v. Kuhn (1972), 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 177 (2008)

- Morgen A. Sullivan, Derelict in the Stream of the Law: Overruling Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 48 Duke L.J. 1265 (1999)

- John Tehranian, It'll Break Your Heart Every Time: Race, Romanticism and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Litigating Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 46 Hofstra L. Rev. 947 (2018)