Ericka Huggins

Ericka Huggins (née Jenkins;[2] born January 5, 1948)[3] is an American activist, writer, and educator. She is a former leading member of the Black Panther Party (BPP).

Ericka Huggins | |

|---|---|

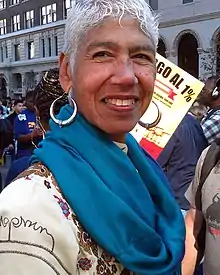

Huggins in 2011 | |

| Born | Ericka Jenkins January 5, 1948[1] Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Education | Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, Lincoln University |

| Occupation | Activist, educator |

| Years active | 1967–present |

| Known for | New Haven Black Panther Trials |

| Political party | Black Panther Party |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Partner(s) | James Mott (1971–1972) |

| Children | 3 |

Early life and education

Born Ericka Jenkins in Washington, D.C.,[4] Huggins was the middle child of three. After graduating high school in 1966, Huggins attended Cheyney State College (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania). She attended Lincoln University studying education, and left after her junior year to join the Black Panther Party.[5] Lincoln University is also where she met her future husband John Huggins, they were married in 1968.[6]

She holds a master's degree in Sociology from.

Career

In 1972, she moved to California and became an elected member of the Berkeley Community Development Council.[7] From 1973 to 1981, Huggins was the Director of the Black Panther Party's Oakland Community School.[3] She also ran the BPP free breakfast program.[8]

Huggins worked in the Peralta Community College District as a professor of sociology and African American studies from 2008 to 2015; teaching at both Laney College and at Berkeley City College.[9][10][11] In addition, she has lectured at Stanford University, Cornell University, and University of California, Los Angeles.[10]

Black Panther Party

After joining the party in 1968,[6] Ericka Huggins became a leader in the Los Angeles chapter and later led the Black Panther Party chapter in New Haven, Connecticut, along with two other women, Kathleen Neal Cleaver and Elaine Brown.[12]

Her husband John Huggins, was a leader in the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party.[6][3] John Huggins was assassinated on January 17, 1969, on the UCLA campus[13] because of a feud between the Black Panther Party and a Black Nationalist group, US Organization, that was fueled by the COINTELPRO program, a series of covert and illegal projects conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting American political organizations.[14] Ericka Huggins attended the burial of her husband in his birthplace of New Haven.

New Haven Black Panther trials

In 1969, members of the New Haven Black Panthers tortured and murdered Alex Rackley, whom they suspected of being an informant. Along with Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale, Huggins was charged with murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy.[15] Huggins was heard speaking on a tape recording of Rackley's interrogation that was played during the trial.[16] The trial sparked protests across the country about whether the Panthers would receive a fair trial and the jury selection would become the longest in state history. In May 1971 the jury deadlocked 10 to 2 for Huggins' acquittal, and she was not retried.[17]

Personal life

Ericka Huggins married John Huggins in 1968.[6] Ericka gave birth to their daughter, Mai Huggins, at the age of 20.[18][19] Within three months of their daughter's birth, Ericka became a widow when John Huggins was killed on the UCLA campus in January 1969.

Huggins has two sons. One of her sons is Rasa Sun Mott,[18] which she had with James Mott, lead singer of the Lumpen, the Black Panthers singing group.[20][21]

References

- Bloom, Joshua; Martin, Waldo E. Jr (January 14, 2013). Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95354-3.

- "Film/Documentary/TV", Valerie C. Woods website.

- Shih, Bryan; Williams, Yohuru (September 13, 2016). The Black Panthers: Portraits from an Unfinished Revolution. PublicAffairs. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-56858-556-7.

- Scheffler, Judith A. (June 16, 1986). Wall Tappings: An Anthology of Writings by Women Prisoners. Northeastern University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-55553-042-6.

- Gore, Dayo F.; Theoharis, Jeanne; Woodard, Komozi (2009). Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. NYU Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8147-8314-6.

- Hine, Darlene Clark (2005). Black Women in America: A-G. Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-19-515677-5.

- "Black Panthers Win Elections in Berkeley", Jet, June 29, 1972, p. 7.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (2006). Creating Black Americans: African-American History and Its Meanings, 1619 to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-19-513756-9.

- "Huggins, Ericka". Archives at Yale.

- "bio cont'd". Erickahuggins.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- "A conversation with leading Black Panther Party member, human rights advocate and poet Ericka Huggins". USC Annenberg. April 19, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- Hine, Darlene (1998). A Shining Thread of Hope. New York, NY: Broadway Books. pp. 298. ISBN 0-7679-0111-8.

- "Are We Better Off? | The Two Nations Of Black America | FRONTLINE". PBS. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- Gentry, Curt, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets. W. W. Norton & Company (2001), p. 622.

- Alan Lenhoff (March 20, 1971). "Testimony Continues in Seale, Huggins Trial". Michigan Daily.

- Paul Bass, Black Panther Torture "Trial" Tape Surfaces, New Haven Independent, February 21, 2013.

- Paul Bass; Douglas W. Rae (2006). Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, And the Redemption of a Killer. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-06902-6.

- Williams, Lena (March 28, 1993). "Revolution Redux?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- "Former Black Panther Visits UK | UK College of Arts & Sciences". As.uky.edu. March 23, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- Wall, Alix (November 30, 2001). "Black Panther son opening Rasa Caffe in Berkeley". Berkeleyside. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- "Rasa Mott unites his local roots and world travels in South Berkeley cafe". Berkeleyside. February 15, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ericka Huggins. |