Corp Naomh

The Corp Naomh ([kɔɾˠpˠ n̪ˠiːvˠ], English: Holy or Sacred Body) is a 10th-century Irish reliquary bell-shrine rediscovered before 1682 at Tristernagh Abbey, near Templecross, County Westmeath. It is made from a hollow wooden core lined with bronze and decorated with silver, niello and rock crystal. Built to hold a saint's bell, it is badly damaged, and when discovered a block of wood had been substituted for the bell itself. The original late 10th-century shrine was extensively refurbished in the 15th and 16th centuries when elements such as the central bronze crucifixion of Jesus, the griffin and lion panel, the stamped border panels and the backing plate were added.

| Corp Naomh | |

|---|---|

%252C_argento_e_bronzo_con_cristallo_di_rocca%252C_da_Templecross%252C_co._Westmeath%252C_x_poi_xv_secolo%252C_01.jpg.webp) | |

| Material | Wood, silver, bronze, rock crystal, niello |

| Size | Height: 23 cm (9.1 in)[1] |

| Created | Late-10th century, added to in the 15th and 16th centuries |

| Period/culture | Early Medieval, Insular |

| Place | Templecross, County Westmeath, Ireland |

| Present location | National Museum of Ireland, Dublin |

| Identification | NMI:1887:145 |

Early sections include the semi-circular plate crest on the top, with cleric holding a book, who is surrounded on both sides by horsemen, above whom are large birds seemingly about to take flight. The main panel contains a badly damaged crucifixion and large enamel stud on the lower part of the front which date from at least from the 15th century. The crest is by far the more ornately decorated part of the shrine, and its motifs are continued on the reverse.

The shrine's historical record is incomplete, but suggests that it was kept by a hereditary keeper after the dissolution of Tristernagh Abbey, until sometime after the 15th century, when it came into the possession of the Anglo-Irish owners of the site of the abbey. It was first exhibited in 1853, and acquired from the Royal Irish Academy in 1887 by the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, where it remains on permanent display.

Discovery and provenance

The shrine was rediscovered sometime before 1682[2] on the grounds of the now ruined Tristernagh Abbey (founded 1190) in Templecross, Co. Westmeath,[3] and first mentioned by Henry Piers (1629–1691), the MP, antiquarian and then-owner of the land on which the abbey was located in his '"History of Westmeath". Although recognised as a reliquary, Piers assumed it to have been a container for a manuscript,[4] although when finally opened it was found to contain a block of wood substituting a tubular saint's bell.[5]

Although the shrine's medieval provenance is unknown, it is generally accepted that the 15th and 16th century additions were made at Tristernagh, where it was located when brought to modern attention by Piers. Historians consider it likely that the priory invested in upgrading the shrine to redeem and re-establish itself after it faced charges of treason in 1468 "for joining with Irish enemies and English rebels in raiding and burning the town of Taghmon and in destroying many of the king’s loyal subjects".[3]

Piers recounts that he received the shrine at Tristernagh from an unknown man he described as "a certain gentleman, a great zealot of the romish church". Cautious not to damage the structure, he did not open the shrine (it was not finally opened until the late 19th century), but guessed that it contained "a bible of the smaller volume" (ie a "pocket bible"), and described the outer casing as "laced...of brass, and...studded over on the one side with pieces of crystal all set in silver....on the other side appears a crucifix of brass, and whether it have any thing hidden within it, is known I believe to no man living, but it...is held to this day in great veneration by all of the Romanish persuasion that live hereabout".[2] He continued that the shrine had an on-going tradition of use for swearing oaths, noting how the object was held in such reverence and was of such "peculiar solemnity", that any man who "delivered falsehoods...is sure to be visited in some dreadful manner".[6]

The shrine was first exhibited at the Irish Industrial Exhibition world's fair held in Cork in 1852, where it was shown alongside such works as the Cathach, Saint Manchan's Shrine and the Cross of Cong.[7] It was acquired by the Royal Irish Academy c. 1853, before it was bequeathed to the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin in 1887.[5]

Description

The title Corp Naomh (Sacred or holy body, at one time known as the Corp Nua)[7][4] is modern and based on the large central figure of Christ on the cross.[8] With a height of 23 cm (9.1 in) it is around the size of a pocket bible, and was thus for centuries assumed to have been a container for a manuscript.[6] It is built from a thin slim wooden core, to which various separately cast plates were added, the earliest of which is the 10th century semi-circular crest at the top of the shrine which is 12 cm (4.7 in) high and made from hard yellow bronze. The stamped border panels and backing plate are 15th century, while the central crucifixion and oval crystal at the lower left hand may be from the 16th century.[8][9]

When acquired by the Royal Irish Academy in 1887, it came with its original leather portable case (polaire).[5]

Crest

The crest is decorated on both sides with patterns and figures that are continuous from front to back.

Cleric

%252C_argento_e_bronzo_con_cristallo_di_rocca%252C_da_Templecross%252C_co._Westmeath%252C_x_poi_xv_secolo%252C_01_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The center of the crest contains a figure in full profile holding a book.[10] He is assumed to be an ecclesiastic based on both this clothing and the fact that he is partially bald, which was often contemporary short-hand for indicating clerics and monks,[n 1] while he may been intended to represent an evangelist given his similarities to the four figures in the 11th century front of the Soiscél Molaisse.[12][13] He has whiskers and a curled beard, and wears a full length tunic rendered with cross hatching on enamel, niello and sandals.[14] His head extends beyond the frame and onto the 1.27 cm (0.50 in) wide semi-circular border above him, which is made of bronze and decorated with running-knot interlace patterns and is likely 15th century.[15]

Each of his shoulders have circular ornaments and cross hatchings resembling early versions of Orthodox Crosses. The historian William Frazer describes the designs and their "equal-rayed limbs" as an examples of the then "popular and universally worn" Patrick's Cross type, which he said were "distinctive emblems of Christian teaching...[that were a] recognised badge of those who possessed rank in the Celtic churches".[14] Other early works containing similar designs include figures on a stone cross from Meigle, Scotland, and the 12th-century Irish Saint Manchan's Shrine.[16] Above these designs are triangular shapes, likely representing brooches used to fix his decorated cloak in place.[17]

Horsemen

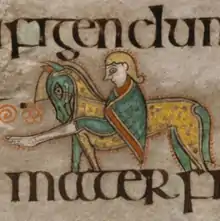

The panels on either side contain rather cramped scenes[13] with riders and horse facing towards him.[9] They are drawn in the a tradition often found on earlier Illuminated manuscripts, high crosses and Insular metalwork, mostly notability on folio 255 of the Book of Kells, after which this so-called "Kells style" tradition has been named.[17] In all examples, the horse is small enough to be a pony, and has a long and thick main, downwards looking eyes and head, and a long and wide tail. Their hind legs are low and underneath their body, while their forelegs are positioned forwards as if about to gallop.[18]

Keeping within the tradition, the Corp Naomh riders hold their hands inside their cloak, and are positioned low on the horses with their legs thrown forward above the horses shoulders. In earlier examples (including the Book of Kells miniature, the late-10th century Clonmacnoise Crucifixion Plaque and warriors on the 11th century shrine of the Stowe Missal), the riders have short fringes, shoulder-length sides and sometimes a bald crown, here and in other later examples their hair is longer and dramatically curls-up at the back.[17][18]

Above the horsemen are two large birds with small curved beaks[10] and long wings that appear as if to take flight. Based on contemporary iconography, Frazer speculates that the birds may represent the martyrdom of the cleric.[14]

.jpg.webp) Horseman in folio 255 (Luke), Book of Kells, 9th century

Horseman in folio 255 (Luke), Book of Kells, 9th century Detail of the horseman on folio 58 of the Book of Kells

Detail of the horseman on folio 58 of the Book of Kells%252C_argento_e_bronzo_con_cristallo_di_rocca%252C_da_Templecross%252C_co._Westmeath%252C_x_poi_xv_secolo%252C_01_(right_hand_cropped).jpg.webp) Rider on the Corp Naomh

Rider on the Corp Naomh

Crucifixion

%252C_argento_e_bronzo_con_cristallo_di_rocca%252C_da_Templecross%252C_co._Westmeath%252C_x_poi_xv_secolo%252C_01_(cropped3).jpg.webp)

The bronze figure of Christ and the silver cross was added in the 15th or 16th centuries but is now badly damaged, while most of the plating around him was 10th century but is now is lost as most of the cross.[19] Equally the 10th century bronze backing is severely damaged especially to the lower right hand side.[8] Christ is naked except for a loincloth and is obviously dead; his eyes are closed, his head droops to the right, his body is rigid and while his ribs are extended, his chest overall is flat.[13] His hands have been lost (and replaced with crudely described rods), while the also damaged horizontal design above his head maybe either a crown or a band of hair.[13]

%252C_argento_e_bronzo_con_cristallo_di_rocca%252C_da_Templecross%252C_co._Westmeath%252C_x_poi_xv_secolo%252C_01_(cropped2).jpg.webp)

Above Christ's left arm is an embossed (ie the metal was hammered into shape from the back) silver panel showing a dragon or griffin and lion confronting each other in symmetrical poses. This was likely one of a series of similar plates surrounding the length of his body, but are now lost.[8] In the panel, the hindlegs of both animals are extended as if they about are about to attack each other.[13] Confronted griffin and lions were a common motif in 15th century Irish art, notably on the c 1493 wooden Dunvegan Cup, a fact that has been used to date the additions to the main panel.[20] The examples from from this period are so similar that a number of art historians have suggested they were copied or based upon die-stamps. The art-historian Susanne McNab speculates that the design on the Corp Naomh comes from the same stamp as the 14th century addition to the Cathach's shrine.[20]

The remnants of other embossed plates survive, including a strip of dotted tetrahedra (triangular pyramidal shapes) lining the left margin, while a floral pattern runs along the top border, but is badly damaged.[13]

Reverse

The back of the 10th century crest is as equally decorated as the front part.[21] The reverse of the lower part contains a grid of small interlinked openwork crosses set on a damaged bronze plate.[8][22] Its crosses are similar to the 15th patterns found on the reverse of the Soiscél Molaisse – an Irish cumdach (book shrine).[17]

It is unknown how the front and reverse originally fitted together; they may have been individually laid over the main sides of a bell, or, as most art historians believe, have formed part of a box-like container for a bell, in a shape similar to the c. 1100 St. Patrick's Bell Shrine, and thus are now missing their side panels which would have been also decorated.[23]

Gallery

%252C_argento_e_bronzo_con_cristallo_di_rocca%252C_da_Templecross%252C_co._Westmeath%252C_02_sacco_in_cuoio_del_xv_sec.jpg.webp) The shrine's portable leather cover

The shrine's portable leather cover Drawing of the reverse with damaged cross, Margaret Stokes, 19th century

Drawing of the reverse with damaged cross, Margaret Stokes, 19th century.jpg.webp) Drawing of the reverse of the Soiscél Molaisse

Drawing of the reverse of the Soiscél Molaisse

Notes

- Semi-bald clerics also appear on the 9th century Book of Kells, the Kells Crozier and Saint Manchan's Shrine, amongst others.[11]

References

- Overbey (2012), p. XII

- Overbey (2012), p. 139

- Overbey (2012), p. 140

- Betham (1826), p. 21

- Frazer (1899), p. 35

- Tristernagh (1846), p. 395

- Overbey (2012), p. 26

- Overbey (2012), p. 137

- Frazer (1899), p. 36

- Overbey (2012), p. 142

- Overbey (2012), p. 62

- Moss (2007), p. 63

- De Paor (1977), p. 182

- Frazer (1899), p. 37

- De Paor (1977), p. 181

- Frazer (1899), p. 38

- Overbey (2012), p. 141

- McNab (2001), p. 178

- Ó Floinn; Wallace (2002), p. 314

- McNab (2001), p. 305

- Ó Floinn; Wallace (2002), p. 272

- Crawford (1923), p. 77

- Overbey (2012), p. 137, 139

Sources

- Betham, William. Irish Antiquarian Researches, 1826. Republished by Palala Press in 2015.

- Crawford, Henry. "A Descriptive List of Irish Shrines and Reliquaries. Part I". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, sixth series, volume 13, No. 1, 30 June 1923. JSTOR 25513282

- De Paor, Marie. "The Viking Impact". In: Treasures of Early Irish Art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.. NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977. ISBN 978-0-8709-9164-6

- Frazer, William. "On "Patrick's Crosses": Stone, Bronze and Gold". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, fifth series, volume 9, No. 1, March 31, 1899

- Henry, Françoise. Irish Art during the Viking Invasions (800–1020 A.D.). London: Methuen & Co, 1967

- McNab, Susanne. Celtic Antecedents to the Treatment of the Human Figure in Early Irish Art. In: Hourihane, Colum (ed.). "From Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian to the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context". Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-6910-8824-2

- Moss, Rachel. Medieval c. 400—c. 1600: Art and Architecture of Ireland. London: Yale University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-3001-7919-4

- Moss, Rachel. Making and Meaning in Insular Art: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Insular Art. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-8518-2986-6

- Ó Floinn, Raghnall; Wallace, Patrick. Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities. Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7171-2829-7

- Overbey, Karen. Sacral Geographies: Saints, Shrines and Territory in Medieval Ireland. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012. ISBN 978-2-503-52767-3

- "Tristernagh". The Parliamentary gazetteer of Ireland (1814-45). Dublin: A. Fullarton and Co., 1846

External links

- The Bells of the Irish Saints, 2021 video lecture by Cormac Bourke of the National Museum of Ireland