Clytie (Oceanid)

Clytie (/ˈklaɪtiiː/; Ancient Greek: Κλυτίη), or Clytia (/ˈklaɪtiə/; Κλυτία from ancient Greek κλυτός, meaning "glorious" or "renowned"[1]) was a water nymph, daughter of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys in Greek mythology.[2][3][4] She was one of the 3,000 Oceanids, thus sister to the Potamoi (river-gods). Clytia loved Helios in vain,[5] but he left her for another woman, the princess Leucothoe. In anger and bitterness, she revealed their affair to the girl's father, indirectly causing her doom as the king buried her alive. This failed to win Helios back to her, and she was left lovingly staring at him from the ground; eventually she turned into a heliotrope, a violet flower that gazes at the Sun.

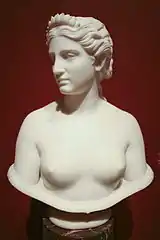

| Clytie | |

|---|---|

| Member of the Oceanids | |

Townley's Clytie | |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Oceanus and Tethys |

| Siblings | The Oceanids, the Potamoi |

| Consort | Helios |

Mythology

She was a lover of Helios, until Aphrodite made him fall in love with a mortal princess, Leucothoe, in order to take revenge on him for telling her husband Hephaestus of her affair with the god of war Ares, whereupon he ceased to care for her. Helios, having loved her, abandoned her for Leucothoe and left her deserted. Angered by his treatment of her, and still missing him, she told Leucothoe's father, Orchamus, about the affair. Since Helios had defiled Leucothoe, Orchamus had her put to death by burial alive in the sands. Helios arrived too late to save the girl, but he did make sure to turn her into a frankincense tree by pouring nectar over her dead body, so that she would still breathe air (in a way).

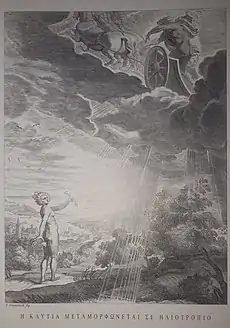

Clytie intended to win Helios back by taking away his new love, but even though "her love might make excuse of grief, and grief may plead to pardon jealous words" her actions only hardened his heart against her, and now he avoided her altogether, never going back to her. In despair, she stripped herself and sat naked, with neither food nor drink, for nine days on the rocks, staring at the sun, Helios, and mourning his departure, but he never looked back at her. After nine days she was transformed into a purple flower, the heliotrope (meaning "sun-turning"[6]), also known as turnsole (which is known for growing on sunny, rocky hillsides),[7] which turns its head always to look longingly at Helios the Sun as he passes through the sky in his solar chariot, even though he no longer cares for her.[8]

Edith Hamilton notes that Clytie's case is unique in Greek mythology, as instead of the typical lovesick god being in love with an unwilling maiden, it's a maiden who is in love with an unwilling god.[9] The episode is most fully told by Roman poet Ovid in his poem the Metamorphoses;[10] Ovid's version is the only surviving narrative of this story, but according to Lactantius Placidus, he got this myth from seventh or sixth century BC Greek author Hesiod.[11] It is possible that originally the stories of Leucothoe and Clytie were two distinct ones before they were combined along with a third story, that of Ares and Aphrodite's affair being discovered by Helios who then informed Hephaestus, into a single one either by Ovid or Ovid's source.[12]

Culture

Similar to the story of Daphne used as an explanation for the plant's prominence in worship, Clytie' story might have been used for similar purposes in connecting the flower she turned into, the heliotrope, to Helios.[13]

An ancient scholiast wrote that the heliotropium that Clytie was turned into was the first preservation of the love for the god.[14]

Modern interpretations

Identity of the flower

Modern traditions substitute the purple[15] turnsole with a yellow sunflower (which is not native to either Greece or Italy, coming from North America[16]), which according to (incorrect) folk wisdom turns in the direction of the sun.[17] The original French form tournesol primarily refers to sunflower, while the English turnsole is primarily used for heliotrope.

It has also been noted that the heliotropium itself poses some difficulties for identification with Clytie's flower; heliotropium arborescens, which is the vivid purple variant, is not native to Europe either, instead coming from the Americas. Native variants of heliotropium or other flowers called "heliotrope" are also the wrong colour, either white (heliotropium supinum) or yellow (vilossum), when Ovid described it as "like a violet" and Pliny "blue".[18] Both however lived in the post-Hellenistic period after the conquests of Alexander the Great, and could have been aware of the heliotropium indicum, a variant that can have a purplish or bluish corolla.[19]

Identity of the god

Much like with Phaethon, another ancient myth featuring Helios, some modern versions connect Clytie and her story to Apollo, but the myth does not actually concern him;[20] Ovid identifies the god Clytie fell in love with as Hyperione nate (the son of Hyperion), and like other Roman authors does not conflate in his poem the two gods, who remain distinct in myth.[21] Clytie's lover whom she was jilted by is also connected to the story of Phaethon, as the boy's father, a distinctly solar but non-Apolline figure, who in turn is not a sun god or given any solar characteristics as far as Ovid is concerned.[12]

Art

Bust (Townley collection)

One sculpture of Clytie, found in the collection of Charles Townley, might be either a Roman work, or an eighteenth century "fake".[22]

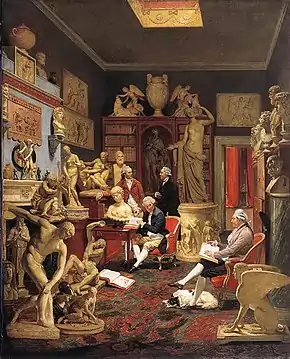

The bust was created between 40 and 50 AD. Townley acquired it from the family of the principe Laurenzano in Naples during his extended second Grand Tour of Italy (1771–1774); the Laurenzano insisted it had been found locally. It remained a favorite both with him (it figures prominently in Johann Zoffany's iconic painting of Townley's library (illustration, right), was one of three ancient marbles Townley had reproduced on his visiting card, and was apocryphally the one which he wished he could carry with him when his house was torched in the Gordon Riots – apocryphal since the bust is in fact far too heavy for that) and with the public (Joseph Nollekens is said to have always had a marble copy of it in stock for his customers to purchase, and in the late 19th century Parian ware copies were all the rage.[23]

The identity of the subject, a woman emerging from a calyx of leaves, was much discussed among the antiquaries in Townley's circle. At first referred to as Agrippina, and later called by Townley Isis in a lotus flower, it is now accepted as Clytie. Some modern scholars even claim the bust is of eighteenth century date, though most now think it is an ancient work showing Antonia Minor or a contemporaneous Roman lady in the guise of Ariadne.

Bust (George Frederick Watts)

Another famous bust of Clytie was by George Frederick Watts.[24] Instead of Townley's serene Clytie, Watts's is straining, looking round at the sun.

Literature

Clytie is briefly alluded to in Thomas Hood's poem Flowers, in the lines "I will not have the mad Clytie,/Whose head is turned by the sun;".[25]

See also

- 73 Klytia, a main-belt asteroid named after this nymph.

- Smilax, another nymph transformed into a plant over love.

- Mecon, a goddess' lover who was transformed into a flower.

- Psalacantha, another nymph transformed into a flower for trying to separate a god from his mortal lover.

- Heliotrope (color)

Notes

- Liddell & Scott (1940), A Greek–English Lexicon, Oxford: Clarendon Press, κλυτός

- Her name appears in the long list of Oceanids in Hesiod, Theogony 346ff.

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface

- Bane, Theresa (2013). Encyclopedia of Fairies in World Folklore and Mythology. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 87. ISBN 9780786471119.

- Two other minor personages name Clytie are noted: see Theoi Project: Clytie.

- Bailly, Anatole (1935) Le Grand Bailly: Dictionnaire grec-français, Paris: Hachette: ἡλιοτρόπιον

- Scholia on in Ovid Metamorphoses 4.267

- Hard, p. 45; Berens, p. 63; March, s.v. Helios; Gantz, p. 34; Tripp, s.v. Helius B; Grimal, s.v. Clytia; Parada, s.v. Leucothoe 2; Seyffert, s. v. Clytia; Cameron, p. 290 writes "Anonymous does not actually name he betrayer of Leucothoë—or Leucothoë's mother (Eurynome in Ovid). Both omissions are probably just consequences of the abridgement."

- Hamilton 2012, p. 275.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.192–270

- Lactantius Placidus, Argumenta 4.5

- Fontenrose, Joseph. The Gods Invoked in Epic Oaths: Aeneid, XII, 175-215. The American Journal of Philology 89, no. 1 (1968): pp 20–38.

- Κακριδής et al. 1986, p. 228.

- Scholia on Ovid's Metamorphoses 4.256; Cameron, p. 8

- In fact, Ovid doesn't name the flower Clytie turned into, but explicitly describes it as violet in colour.

- Flora of North America: Common sunflower, United States Department of Agriculture, Helianthus annuus L.

- Folkard, p. 336

- Bright 2021, pp. 96-97.

- McMullen 1999, p. 219.

- MacDonald Kirkwood, p. 13

- Grummel, William C. “CLYTIE AND SOL.” The Classical Outlook 30, no. 2 (1952): pp 19–19.

- Trustees of the British Museum – Marble bust of 'Clytie' Archived 2012-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Trustees of the British Museum – Parian bust of Clytie Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- The Victorian Web – Clytie George Frederick Watts, R.A., 1817–1904

- Bulfinch, p. 83

References

- Berens, E. M., The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome, Blackie & Son, Old Bailey, E.C., Glasgow, Endinburgh and Dublin. 1880.

- Bright, Henry Arthur (2021). A Year in a Lancashire Garden. Litres. ISBN 9785040620067.

- Bulfinch, Thomas, Greek and Roman Mythology: The Age of Fable, Dover Publications, 2000, unabridged, ISBN 978-0-486-41107-1.

- Cameron, Alan, Greek Mythography in the Roman World, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-517121-7. Google books.

- Folkard, Richard (1884), Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics: Embracing the Myths, Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-Lore of the Plant Kingdom, Folkard & Son.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Grimal, Pierre, A Concise Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1990. ISBN 0-631-16696-3.

- Hamilton, Edith (2012). Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes. London: Hachette. ISBN 978-0-316-03216-2.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Lateinische Mythographen: Lactantius Placidus, Argumente der Metamorphosen Ovids, erstes heft, Dr. B. Bunte, Bremen, 1852, J. Kühtmann & Comp.

- McMullen, Conley K. (1999). Flowering Plants of the Galápagos. Comstock Publishing Associates. ISBN 0-8014-3710-5.

- MacDonald Kirkwood Gordon, A Short Guide to Classical Mythology. Cornell University. 2000. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc, ISBN 0-86516-309-X. Google books

- March, Jennifer R., Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Illustrations by Neil Barrett, Cassel & Co., 1998. ISBN 978-1-78297-635-6.

- Parada, Carlos, Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, Jonsered, Paul Åströms Förlag, 1993. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- Publii Ovidii Nasonis Opera omnia: IV. voluminibus comprehensa : cum integris Jacobi Micylli, Herculis Ciofani, et Danielis Heinsii notis, et Nicolai Heinsii curis secundis, et aliorum singulas partes, partim integris, parti excerptis, adnotationibus, vol. II. Google books.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses. Hugo Magnus. Gotha (Germany). Friedr. Andr. Perthes. 1892. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publis Ovidius Naso. Metamorphoses, Volume I: Books 1-8. Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library No. 42. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1977, first published 1916. ISBN 978-0-674-99046-3. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Seyffert, Oskar, A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, Mythology, Religion, Literature and Art, from the German of Dr. Oskar Seyffert, S. Sonnenschein, 1901.

- Tripp, Edward, Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology, Thomas Y. Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970). ISBN 069022608X.

- Κακριδής, Ιωάννης Θ.; Ρούσσος, Ε. Ν.; Παπαχατζής, Νικόλαος; Καμαρέττα, Αικατερίνη; Σκιαδάς, Αριστόξενος Δ. (1986). Ελληνική Μυθολογία: Οι Θεοί, τόμος 1, μέρος Β΄. Athens: Εκδοτική Αθηνών. p. 228. ISBN 978-618-5129-48-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clytie. |

- Images of Clytie in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database

- CLYTIE from The Theoi Project

- CLYTIE from greekmythology.com