Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office (10 U.S.C. § 8033) held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (10 U.S.C. § 151), the CNO is a military adviser to the National Security Council, the Homeland Security Council, the secretary of defense, and the president. The current chief of naval operations is Admiral Michael M. Gilday.

| Chief of Naval Operations | |

|---|---|

Seal of the Chief of Naval Operations | |

Flag of the Chief of Naval Operations | |

| United States Navy Office of the Chief of Naval Operations | |

| Abbreviation | CNO |

| Member of | Joint Chiefs of Staff |

| Reports to | Secretary of the Navy |

| Appointer | The President with Senate advice and consent |

| Term length | 4 years Renewable one time, only during war or national emergency |

| Constituting instrument | 10 U.S.C. § 8033 |

| Precursor | Aide for Naval Operations |

| Formation | 11 May 1915 |

| First holder | ADM William S. Benson |

| Deputy | Vice Chief of Naval Operations |

| Website | www.navy.mil |

Despite the title, the CNO does not have operational command authority over naval forces. The CNO is an administrative position based in the Pentagon, and exercises supervision of Navy organizations as the designee of the secretary of the Navy. Operational command of naval forces falls within the purview of the combatant commanders who report to the secretary of defense.

Appointment, rank, and responsibilities

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is typically the highest-ranking officer on active duty in the U.S. Navy unless the chairman and/or the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff are naval officers.[1] The CNO is nominated for appointment by the president, for a four-year term of office,[2] and must be confirmed by the Senate.[2] A requirement for being Chief of Naval Operations is having significant experience in joint duty assignments, which includes at least one full tour of duty in a joint duty assignment as a flag officer.[2] However, the president may waive those requirements if he determines that appointing the officer is necessary for the national interest.[2] The chief can be reappointed to serve one additional term, but only during times of war or national emergency declared by Congress.[2] By statute, the CNO is appointed as a four-star admiral.[2]

As per 10 U.S.C. § 8035, whenever there is a vacancy for the chief of naval operations or during the absence or disability of the chief of naval operations, and unless the president directs otherwise, the vice chief of naval operations performs the duties of the chief of naval operations until a successor is appointed or the absence or disability ceases.[3]

Department of the Navy

The CNO also performs all other functions prescribed under 10 U.S.C. § 8033, such as presiding over the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV), exercising supervision of Navy organizations, and other duties assigned by the secretary or higher lawful authority, or the CNO delegates those duties and responsibilities to other officers in OPNAV or in organizations below.[1][4]

Acting for the secretary of the Navy, the CNO also designates naval personnel and naval forces available to the commanders of unified combatant commands, subject to the approval of the secretary of defense.[4][5]

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The CNO is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as prescribed by 10 U.S.C. § 151 and 10 U.S.C. § 8033. Like the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the CNO is an administrative position, with no operational command authority over the United States Navy forces.

Members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, individually or collectively, in their capacity as military advisers, shall provide advice to the president, the National Security Council (NSC), or the secretary of defense (SECDEF) on a particular matter when the president, the NSC, or SECDEF requests such advice. Members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (other than the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) may submit to the chairman advice or an opinion in disagreement with, or advice or an opinion in addition to, the advice presented by the chairman to the president, NSC, or SECDEF.

When performing his JCS duties, the CNO is responsible directly to the SECDEF, but keeps SECNAV fully informed of significant military operations affecting the duties and responsibilities of the SECNAV, unless SECDEF orders otherwise.[6]

History

Early attempts (1902–1909)

The earliest attempts to reform the Navy's management structure under a single commissioned officer began in response to President Theodore Roosevelt's massive buildup of naval power, in concert with his "Big Stick" implementation of foreign policy.[7] The closest thing the Navy had to an executive body at the time was the General Board of the United States Navy, established in 1900,[8] but the Board lacked the necessary authority to sufficiently reorganize the Navy.[8] Among the critics of the disorganized command structure and proponents of rapid modernization included Charles J. Bonaparte, Roosevelt's fourth Navy secretary from 1905 to 1906,[9] Reginald R. Belknap,[10] Albert Key, and William Sims, Roosevelt's naval aides from 1905 to 1907 and 1907 to 1909 respectively.[7]

Rear Admiral George A. Converse, commander of the Bureau of Navigation (BuNav) from 1905 to 1906, reported:

[W]ith each year that passes the need is painfully apparent for a military administrative authority under the Secretary, whose purpose would be to initiate and direct the steps necessary to carry out the Department’s policy, and to coordinate the work of the bureaus and direct their energies toward the effective preparation of the fleet for war.[11]

However, proposals to establish a permanent body to manage the disparate bureaus and offices faced vehement disapproval from Congress, partially due to fears of creating a Prussian-style general staff and because several of such proposals granted greater authority to the secretary of the Navy over the officer promotion system, both of which risked infringing on legislative authority.[12] In particular, Senator Eugene Hale, chairman of the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs from 1897 to 1909, disliked reformers like Sims[13] and persistently blocked attempts to bring such ideas for debate, including those of a special board convened by Roosevelt in 1909 which supported immediate change.[14]

Aide for Naval Operations (1909–1915)

To circumvent the opposition, George von Lengerke Meyer, Secretary of the Navy under Roosevelt's successor William Howard Taft implemented a system of "aides" on 18 November 1909,[12] including aides for personnel, material, inspections, and operations.[12][15] These four senior officers, with the rank of rear admiral, did not have command authority and instead served as principal advisors to the Secretary, charged with supervising and coordinating the functions of their respective bureaus.[12] Meyer deemed the aide for operations to be the most important of the four, responsible for devoting "his entire attention and study to the operations of the fleet,"[16] and drafting orders for the movement of ships on the advice of the General Board and approval of the Secretary in times of war or emergency.[16]

The first aide for operations was Rear Admiral Richard Wainwright,[17] who immediately exercised the influence he had to recommend significant reorganization of the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets to better fit contemporary mission needs.[16] The effectiveness of the arrangement factored into Meyer's decision to grant his newly appointed third aide for operations, Rear Admiral Bradley A. Fiske, de facto status as his principal advisor on 10 February 1913.[18] Fiske retained his post under Meyer's successor, Josephus Daniels.[19]

Creation of the office of the Chief of Naval Operations (1915)

It was under Secretary Daniels and Admiral Fiske that efforts to definitively establish a professional head of the Navy began. Daniels and Fiske, however, often clashed, and their contrasting temperaments often led to debates by both Congress and the executive branch as to whose vision for the Navy was more effective based on individual like or dislike for one or the other.[20] Consequently, the legislation providing for the office of "a chief of naval operations" in 1914 was the result of Fiske going behind Daniels' back, frustrated at the Secretary's ambivalence towards his assertions that the Navy was unprepared for the possibility of being "drawn into" World War I.[21] Early forms of the legislation were the product of Fiske's collaboration with Representative Richmond P. Hobson, a retired Navy admiral.[21] The preliminary proposal (passed off as Hobson's own to mask Fiske's involvement), in spite of Daniels' opposition, passed Hobson's subcommittee unanimously on 4 January 1915,[21] and passed the full House Committee on Naval Affairs on 6 January.[20]

Fiske's younger supporters expected him to be named the first chief of naval operations,[22] and his versions of the bill presented for passage in the Senate provided for the minimum of rank of the officeholder to be a two-star rear admiral.[22]

There shall be a Chief of Naval Operations, who shall be an officer on the active list of the Navy not below the grade of Rear Admiral, appointed for a term of four years by the President, by and with the advice of the Senate, who, under the Secretary of the Navy, shall be responsible for the readiness of the Navy for war and be charged with its general direction.[22]

— Fiske's version of the bill

In contrast, Daniels' version, included in the final bill, emphasized the office's subordination to the secretary of the Navy, allowed for the selection of the CNO from officers of the rank of captain, and denied it authority over the Navy's general direction, tantamount to giving the CNO executive authority:[22]

There shall be a Chief of Naval Operations, who shall be an officer on the active list of the Navy appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, from the officers of the line of the Navy not below the grade of Captain for a period of four years, who shall, under the direction of the Secretary, be charged with the operations of the fleet, and with the preparation and readiness of plans for its use in war.[22]

— Daniels' version of the bill

Fiske's "end-running" of the secretary, while successful in enshrining a professional head of the Navy within statutory law, had permanently tarnished him as insubordinate to Daniels, and eliminated any possibility of him being named the first CNO.[22] Nevertheless, Fiske, satisfied with the change he had helped enact, made a final contribution: elevating the statutory rank of the CNO to admiral with commensurate pay.[22][23] The Senate passed the appropriations bill creating the CNO position and its accompanying office on 3 March 1915.[24] Simultaneously, the system of naval aides promulgated under Meyer was also abolished. Fiske himself retired in 1916, after a year's tour at the Naval War College.[25]

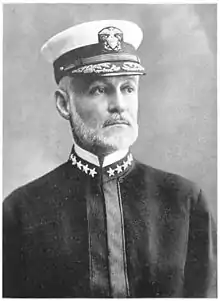

Benson, the first CNO

Captain William S. Benson was promoted to the temporary rank of rear admiral and become the first CNO on 11 May 1915.[24] He further assumed the rank of admiral after the passage of the 1916 Naval Appropriations Bill with Fiske's amendments,[23] second only at the time of passage to Admiral of the Navy George Dewey, and explicitly superior to the commanders-in-chief of the Atlantic, Pacific and Asiatic Fleets.[26]

Early achievements

CNO Benson faced three principal tasks: defining where the chief of naval operations stood within the command hierarchy,[24] forging a productive working relationship with and demonstrating loyalty to Secretary Daniels,[24] and preparing the Navy for potential involvement in World War I without violating the government's official policy of neutrality.[27] Benson thus differed from his predecessor Fiske who campaigned for a powerful, aggressive CNO sharing authority with the secretary of the Navy[24] by demonstrating personal loyalty to the secretary and subordinating himself to civilian control in all matters,[24] thereby alienating reformers like Sims.[28] At the same time, this gave Daniels immense trust in his new CNO, especially in dealing with more troublesome officers like Fiske and Sims on a daily basis,[29] and he rewarded Benson by delegating greater resources and authority to the CNO.[30]

Nevertheless, this did not stop him from maintaining a need for autonomy when he felt it necessary.[28] Benson also intended to disprove those of the officer corps who "spent much of their time criticizing him"[28] for pacifist views perceived to be shared with President Woodrow Wilson, who proclaimed a policy of neutrality in World War I in August 1914.[31]

Among the organizational efforts initiated or recommended by Benson included an advisory council to coordinate high-level staff activities,[32] composed of himself, the SECNAV and the bureau chiefs which "worked out to the great satisfaction" of Daniels and Benson;[32] the reestablishment of the Joint Army and Navy Board in 1918 with Benson as its Navy member;[33][32] and the consolidation of all matters of naval aviation under the authority of the CNO.[32] In all these efforts, Benson remained subordinate to the secretary of the Navy while still being involved in all important decisions affecting the Navy.[23] Benson also had the task of assisting Secretary Daniels with the modernization of the Navy, specifically through advising him of developments in naval technologies and ships.[23]

Most importantly for the future war, Benson revamped the structure of the naval districts,[32] transferring authority for them from SECNAV to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations under the Operations, Plans, Naval Districts division.[34] This enabled closer cooperation between naval district commanders and the uniformed leadership, who could more easily handle communications between the former and the Navy's fleet commanders.[34]

World War I and the establishment of OPNAV

.png.webp)

Early 1916 saw the formal establishment of the CNO's "general staff", the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV), originally called the Office for Operations.[34] Until then, the CNO's office was assigned few personnel: three subordinates (one captain and two lieutenants), no clerical staff, and small, unaccommodating office space on the first day of Benson's tenure.[24] With Hale's retirement from politics in 1911,[35] congressional opinion shifted from fear of a Prussian-style general staff to skepticism of whether the CNO's staff could implement President Wilson's policy of "preparedness" within the limits of official neutrality.[34]

By June 1916, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations was organized into eight divisions: Operations, Plans, Naval Districts;[34] Regulations;[34] Ship Movements;[34] Communications;[34] Publicity;[34] and Materiel.[34] Operations provided a link between fleet commanders and the General Board, Ship Movements coordinated the movement of Navy vessels and oversaw navy yard overhauls, Communications accounted for the Navy's developing radio network, Publicity conducted the Navy's public affairs, providing stories and information to newspapers, and the Materiel section coordinated the work of the naval bureaus.[34]

Until 1918, OPNAV was severely understaffed, numbering only 75 in January 1917, barely adequate for Benson's needs.[36] The office saw a significant increase in size following American entry into World War I, as it was deemed of great importance to manage the rapid mobilization of forces to fight in the war.[37] Among the tasks OPNAV was charged with included specifying the wartime responsibilities of the naval districts,[36] sourcing and producing enough transports for the Army divisions being transferred to the war's western front,[36] and coordinating convoy escorts with the British.[36][38] The 75 initially assigned to OPNAV in 1917 had ballooned to over 1462 by war's end.[39] This caused the CNO and OPNAV to gain great influence over Navy administration but at the expense of the General Board, which had little power to begin with, and more importantly, at the expense of the secretary and naval bureaus.[37]

Advisor to the president

.jpg.webp)

Benson also demonstrated the usefulness of the CNO as a direct advisor to the President of the United States on matters outside of the United States Navy relating to larger diplomatic and strategic concerns.[39] In 1918, Benson became a military advisor to Edward M. House, an advisor and confidant of President Wilson,[39] joining him on a trip to Europe as the 1918 armistice with Germany was signed.[39] His stance that the United States remain equal to Great Britain in naval power proved very useful to House and Wilson, enough for Wilson to insist Benson remain in Europe until after the Treaty of Versailles was signed in July 1919.[39]

End of tenure

Benson's tenure as chief of naval operations was slated to end on 10 May 1919,[40] but this was delayed by the president at Secretary Daniels's insistence.[40] In the waning years of his tenure, Benson presided over a final reorganization of OPNAV, focusing on preventing feuds between the different divisions and setting regulations for officers on shore duty to have temporary assignments with OPNAV, so as to maintain cohesion between the higher-level staff and the fleet.[41] Thus, Admiral Benson retired on 25 September 1919[42] having reformed the Navy's leadership structure, and with his involvement with President Wilson and House on the Treaty of Versailles demonstrated the usefulness of the CNO as a presidential advisor on strategic and diplomatic matters.[41] Admiral Robert Coontz replaced Benson as CNO on 1 November 1919.

Interwar period (1919–1939)

The CNO's office faced no significant changes in authority during the interwar period, largely due to the secretaries of the Navy opting to keep executive authority within their own office. Innovations during this period included encouraging coordination in war planning process, and compliance with the Washington Naval Treaty[43][44] while still keeping to the shipbuilding plan authorized by the Naval Act of 1916.[45] and implementing the concept of naval aviation into naval doctrine.

CNO Pratt, relationship with the General Board and Army-Navy relations

William V. Pratt became the fifth Chief of Naval Operations on 17 September 1930.[46] He had previously served as assistant chief of naval operations under CNO Benson,[47] and had proven pivotal to bridging the gap between Benson and Daniels with equal experience as a protégé of Vice Admiral Sims, whose outspokenness regarding wartime deficiencies and the power granted to the CNO earned him a poor reputation among higher-ups in the Department of the Navy and OPNAV.[48] A premier naval policymaker and supporter of arms control under the Washington Naval Treaty, Pratt clashed with President Herbert Hoover over building up naval force strength to treaty levels,[49] with Hoover favoring restrictions in spending due to financial difficulties caused by the Great Depression.[50] Under Pratt, such a "treaty system" was intended to maintain a compliant peacetime navy.[49]

Pratt opposed centralized management of the Navy, and encouraged diversity of opinion between the offices of the Navy secretary, CNO and the Navy's General Board.[51] To this effect, Pratt removed the CNO as an ex officio member of the General Board,[51] concerned that the office's association with the Board could hamper diversities of opinion between the former and counterparts within the offices of the Navy secretary and OPNAV.[51] This was in conflict with the powerful Representative Carl Vinson of Georgia, chair of the House Naval Affairs Committee from 1931 to 1947, a proponent of centralizing power within OPNAV who deliberately delayed many of his planned reorganization proposals until Pratt's replacement by William H. Standley to avoid the unnecessary delays that would otherwise have happened with Pratt.[52]

Pratt also enjoyed a good working relationship with Army chief of staff Douglas MacArthur, and negotiated several key agreements with him over coordinating their services' radio communications networks, mutual interests in coastal defense, and authority over Army and Navy aviation.[53]

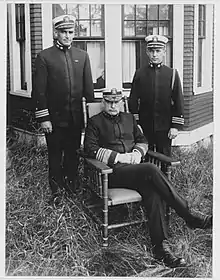

Standley and Leahy, preparing for war

_shakes_hands_with_Admiral_Joseph_M._Reeves_NH_47298.jpg.webp)

William H. Standley, who succeeded Pratt in 1933, had a weaker relationship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt than Pratt enjoyed with Hoover,[52] and was often in direct conflict with secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson and assistant secretary Henry L. Roosevelt. In fact, Standley's hostility to the assistant secretary was described as "poisonous" on occasion.[52] On the other hand, Standley successfully improved relations with Congress, streamlining communications between the Department of the Navy and the naval oversight committees by appointing the first naval legislative liaisons, the highest-ranked of which reported to the judge advocate general.[54] Most importantly, Standley worked with Representative Vinson to pass the Vinson-Trammell Act, considered by Standley to be his most important achievement as CNO. The Act authorized the President:

“to suspend” construction of the ships authorized by the law “as may be necessary to bring the naval armament of the United States within the limitation so agreed upon, except that such suspension shall not apply to vessels actually under construction on the date of the passage of this act.”[55]

This effectively provided security for all Navy vessels under construction; even if new shipbuilding projects could not be initiated, shipbuilders with new classes under construction could not legally be obliged to cease operations, which consequently allowed the Navy to adequately prepare for World War II without breaking potential limits imposed by future arms control conferences.[55] The Act also granted the CNO "soft oversight power" of the naval bureaus which nominally lay with the secretary of the Navy,[56] as Standley gradually inserted OPNAV into the ship design process.[56] Under Standley, the "treaty system" created by Pratt was followed and eventually abandoned.[50]

William D. Leahy, who would replace Standley as CNO, pursued similar directives.[57] Leahy's close personal friendship with President Roosevelt since his days as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, as well as good relationships with Representative Vinson and Secretary Swanson[58] brought him to the forefront of potential candidates for the post.[57] The incumbent CNO opposed the appointment, as he had previously clashed with Leahy over the CNO's authority over the naval bureaus and even attempted to block Leahy from being assigned a fleet command in retaliation.[58] With Vinson's backing, Leahy oversaw significant reforms to the officer promotion system,[59] which after protracted negotiations with Congress resulted in an increase in available slots for Navy line officers and permitted retirement pensions for senior officers who failed to meet standards for promotion.[60] Even by 1938, however, this failed to increase the selection of officers available for assignment to seaborne command billets.[60]

Leahy retired from the Navy on 1 August 1939 to become Governor of Puerto Rico, a month before the invasion of Poland.[61] The outgoing Commander, Cruisers, Battle Force, Admiral Harold Rainsford Stark replaced him on the same day.

Official residence

Number One Observatory Circle, located on the northeast grounds of the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, DC, was built in 1893 for its superintendent. The chief of naval operations liked the house so much that in 1923 he took over the house as his own official residence. It remained the residence of the CNO until 1974, when Congress authorized its transformation to an official residence for the vice president.[62] The chief of naval operations currently resides in Quarters A in the Washington Naval Yard.

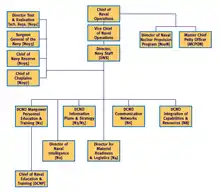

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations presides over the Navy Staff, formally known as the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV).[63][64] The Office of the Chief of Naval Operations is a statutory organization within the executive part of the Department of the Navy, and its purpose is to furnish professional assistance to the secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) and the CNO in carrying out their responsibilities.[65][66]

Under the authority of the CNO, the director of the Navy Staff (DNS) is responsible for day-to-day administration of the Navy Staff and coordination of the activities of the deputy chiefs of naval operations, who report directly to the CNO.[67] The office was previously known as the assistant vice chief of naval operations (AVCNO) until 1996,[68] when CNO Jeremy Boorda ordered its redesignation to its current name.[68] Previously held by a three-star vice admiral, the position became a civilian's billet in 2018. The present DNS is Andrew S. Haueptle, a retired Marine Corps colonel.[69]

List of chiefs of naval operations

(† - died in office)

Aide for Naval Operations (historical predecessor office)

| No. | Portrait | Aide for Naval Operations | Took office | Left office | Time in office | Secretaries of the Navy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rear Admiral Richard Wainwright (1849–1926) | 3 December 1909 | 12 December 1911 | 2 years, 9 days | George von Lengerke Meyer | |

| 2 | Rear Admiral Charles E. Vreeland (1852–1916) | 12 December 1911 | 11 February 1913[70] | 1 year, 61 days | George von Lengerke Meyer | |

| 3 | Rear Admiral Bradley A. Fiske (1854–1942) | 11 February 1913 | 1 April 1915 | 2 years, 49 days | George von Lengerke Meyer Josephus Daniels |

Chief of Naval Operations

| No. | Portrait | Chief of Naval Operations | Took office | Left office | Time in office | Background | Secretaries of the Navy | Secretaries of Defense | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Admiral William S. Benson (1855–1932) | 11 May 1915 | 25 September 1919 | 4 years, 137 days | Battleships | Josephus Daniels | None | ||

| Position vacant (25 September 1919 – 1 November 1919) | |||||||||

| 2 | Admiral Robert E. Coontz (1864–1935) | 1 November 1919 | 21 July 1923 | 3 years, 262 days | Battleships | Josephus Daniels Edwin C. Denby | None | ||

| 3 | Admiral Edward W. Eberle (1864–1929) | 21 July 1923 | 14 November 1927 | 4 years, 116 days | Battleships | Edwin C. Denby Curtis D. Wilbur | None | ||

| 4 | Admiral Charles F. Hughes (1866–1934) | 14 November 1927 | 17 September 1930 | 3 years, 3 days | Battleships | Curtis D. Wilbur Charles F. Adams III | None | ||

| 5 | Admiral William V. Pratt (1869–1957) | 17 September 1930 | 30 June 1933 | 2 years, 286 days | Battleships | Charles F. Adams III Claude A. Swanson | None | ||

| 6 | Admiral William H. Standley (1872–1963) | 1 July 1933 | 1 January 1937 | 3 years, 184 days | Battleships | Claude A. Swanson | None | ||

| 7 | Admiral William D. Leahy (1875–1959) | 2 January 1937 | 1 August 1939 | 2 years, 211 days | Battleships | Claude A. Swanson Charles Edison | None | ||

| 8 | Admiral Harold R. Stark (1880–1972) | 1 August 1939 | 2 March 1942 | 2 years, 213 days | Battleships/Cruisers-Destroyers | Charles Edison Frank Knox | None | ||

| 9 | Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King (1878–1956) | 2 March 1942 | 15 December 1945 | 3 years, 288 days | Aviation | Frank Knox James Forrestal | None | ||

| 10 | Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (1885–1966) | 15 December 1945 | 15 December 1947 | 2 years, 0 days | Submarines | James Forrestal John L. Sullivan | None James Forrestal | ||

| 11 | Admiral Louis E. Denfeld (1891–1972) [lower-alpha 1] | 15 December 1947 | 2 November 1949 | 1 year, 322 days | Submarines | John L. Sullivan Francis P. Matthews | James Forrestal Louis A. Johnson | ||

| 12 | Admiral Forrest P. Sherman (1896–1951) [lower-alpha 2] | 2 November 1949 | 22 July 1951 † | 1 year, 262 days | Battleships/Cruisers-Destroyers | Francis P. Matthews | Louis A. Johnson George C. Marshall | ||

| - | Admiral Lynde D. McCormick (1895–1956) Acting | 22 July 1951 | 16 August 1951 | 25 days | Battleships/Cruisers-Destroyers | Francis P. Matthews Dan A. Kimball | George C. Marshall | ||

| 13 | Admiral William M. Fechteler (1896–1967) | 16 August 1951 | 17 August 1953 | 2 years, 1 day | Battleships/Cruisers-Destroyers | Dan A. Kimball Robert B. Anderson | George C. Marshall Robert A. Lovett | ||

| 14 | Admiral Robert B. Carney (1895–1990) | 17 August 1953 | 17 August 1955 | 2 years, 0 days | Battleships/Cruisers-Destroyers | Robert B. Anderson Charles S. Thomas | Charles Erwin Wilson | ||

| 15 | Admiral Arleigh A. Burke (1901–1996) | 17 August 1955 | 1 August 1961 | 5 years, 349 days | Cruisers-Destroyers | Charles S. Thomas Thomas S. Gates Jr. William B. Franke John Connally | Charles Erwin Wilson Neil H. McElroy Thomas S. Gates Jr. Robert McNamara | ||

| 16 | Admiral George W. Anderson Jr. (1906–1992) [lower-alpha 3] | 1 August 1961 | 1 August 1963 | 2 years, 0 days | Aviation | John Connally Fred Korth | Robert McNamara | ||

| 17 | Admiral David L. McDonald (1906–1997) | 1 August 1963 | 1 August 1967 | 4 years, 0 days | Aviation | Fred Korth Paul Nitze | Robert McNamara | ||

| 18 | Admiral Thomas H. Moorer (1912–2004) [lower-alpha 4] | 1 August 1967 | 1 July 1970 | 2 years, 334 days | Aviation | Paul R. Ignatius John Chafee | Robert McNamara Clark Clifford Melvin Laird | ||

| 19 | Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt (1920–2000) | 1 July 1970 | 29 June 1974 | 3 years, 363 days | Cruisers-Destroyers | John Chafee John Warner J. William Middendorf | Melvin Laird Elliot Richardson James R. Schlesinger | ||

| 20 | Admiral James L. Holloway III (1922–2019) | 29 June 1974 | 1 July 1978 | 4 years, 2 days | Aviation | J. William Middendorf W. Graham Claytor Jr. | James R. Schlesinger Donald Rumsfeld Harold Brown | ||

| 21 | Admiral Thomas B. Hayward (1924–2022) | 1 July 1978 | 30 June 1982 | 3 years, 364 days | Aviation | W. Graham Claytor Jr. Edward Hidalgo John Lehman | Harold Brown Caspar Weinberger | ||

| 22 | Admiral James D. Watkins (1927–2012) [lower-alpha 5] | 30 June 1982 | 30 June 1986 | 4 years, 0 days | Submarines | John Lehman | Caspar Weinberger | ||

| 23 | Admiral Carlisle A.H. Trost (1930–2020) | 1 July 1986 | 29 June 1990 | 3 years, 363 days | Submarines | John Lehman Jim Webb William L. Ball Henry L. Garrett III | Caspar Weinberger Frank Carlucci Dick Cheney | ||

| 24 | Admiral Frank B. Kelso II (1933–2013) [lower-alpha 6] | 29 June 1990 | 23 April 1994 | 3 years, 298 days | Submarines | Henry L. Garrett III Sean O'Keefe John H. Dalton | Dick Cheney Leslie Aspin William J. Perry | ||

| 25 | Admiral Jeremy M. Boorda (1939–1996) [lower-alpha 7] | 23 April 1994 | 16 May 1996 † | 2 years, 23 days | Cruisers-Destroyers | John H. Dalton | William J. Perry | ||

| 26 | Admiral Jay L. Johnson (born 1946) [lower-alpha 8] | 16 May 1996 | 21 July 2000 | 4 years, 66 days | Aviation | John H. Dalton Richard Danzig | William J. Perry William Cohen | ||

| 27 | Admiral Vernon E. Clark (born 1944) | 21 July 2000 | 22 July 2005 | 5 years, 1 day | Cruisers-Destroyers | Richard Danzig Gordon R. England | William Cohen Donald Rumsfeld | ||

| 28 | Admiral Michael G. Mullen (born 1946) [lower-alpha 4] | 22 July 2005 | 29 September 2007 | 2 years, 130 days | Cruisers-Destroyers | Gordon R. England Donald C. Winter | Donald Rumsfeld Robert Gates | ||

| 29 | Admiral Gary Roughead (born 1951) | 29 September 2007 | 23 September 2011 | 3 years, 359 days | Cruisers-Destroyers | Donald C. Winter Ray Mabus | Robert Gates Leon Panetta | ||

| 30 | Admiral Jonathan W. Greenert (born 1953) | 23 September 2011 | 18 September 2015 | 3 years, 360 days | Submarines | Ray Mabus | Leon Panetta Chuck Hagel Ash Carter | ||

| 31 | Admiral John M. Richardson (born 1960) | 18 September 2015 | 22 August 2019 | 3 years, 338 days | Submarines | Ray Mabus Richard V. Spencer | Ash Carter Jim Mattis | ||

| 32 | Admiral Michael M. Gilday (born 1962) | 22 August 2019 | Incumbent | 2 years, 249 days | Cruisers-Destroyers/Cyberspace | Richard V. Spencer Kenneth Braithwaite Carlos Del Toro | Mark Esper Lloyd Austin | ||

See also

Notes

- "Chief of Naval Operations". United States Navy. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "10 USC 5033. Chief of Naval Operations". Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- "10 USC 5035. Vice Chief of Naval Operations". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "10 USC 165. Combatant commands: administration and support".

- "10 USC 5033. Chief of Naval Operations". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Hone & Utz, p. 8.

- Hone & Utz, p. 2.

- Hone & Utz, p. 6-7.

- Hone & Utz, p. 5.

- Hone & Utz, p. 7-8.

- Hone & Utz, p. 10.

- Hone & Utz, p. 9.

- Hone & Utz, p. 3.

- "Navy - Chief of Naval Operations". International Military Digest. 1 (1): 68. June 1915.

- Hone & Utz, p. 11.

- "The Chiefs of Naval Operations and Admiral's House, Volume 2". 1969. p. 11.

- Thomas C. Hone and Curtis A. Utz. "History of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1915-2015" (PDF). p. 12. "On 10 February 1913, with just three weeks remaining to the Taft presidency, Meyer appointed Rear Admiral Bradley A. Fiske his Aide for Operations, and he “made the Aide for Operations his liaison man with all the offices and bureaus of the department.”

- Hone & Utz, p. 12.

- Hone & Utz, p. 14-15.

- Hone & Utz, p. 14.

- Hone & Utz, p. 15.

- Hone & Utz, p. 32.

- Hone & Utz, p. 25.

- "Bradley Allen Fiske". www.arlingtoncemetery.net.

- Hone & Utz, p. 34.

- Hone & Utz, p. 25-26.

- Hone & Utz, p. 29.

- Hone & Utz, p. 47-48.

- Hone & Utz, p. 48.

- Glass, Andrew (8 August 2009). "U.S. proclaims neutrality in World War I, August 4, 1914". Politico.

- Hone & Utz, p. 31.

- the final form of which was agreed by Daniels and the secretary of war, Newton D. Baker

- Hone & Utz, p. 33.

- "Hale Soon to Retire". California Digital Newspaper Collection. Stockton Independent. 20 April 1910.

- Hone & Utz, p. 36.

- Hone & Utz, p. 44.

- Paul E. Fontenoy, "Convoy System", The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History, Volume 1, Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 312–14.

- Hone & Utz, p. 45.

- Hone & Utz, p. 46.

- Hone & Utz, p. 47.

- "Admiral William S. Benson, First Chief of Naval Operations (May 11, 1915–September 25, 1919)". Naval History and Heritage Command.

- Hone & Utz, p. 73.

- Hone & Utz, p. 83.

- Hone & Utz, p. 57.

- "Admiral William V. Pratt, Fifth Chief of Naval Operations (September 17, 1930–June 30, 1933)". Naval History and Heritage Command.

- Hone & Utz, p. 28.

- Hone & Utz, p. 41.

- Hone & Utz, p. 93.

- Hone & Utz, p. 94.

- Hone & Utz, p. 99.

- Hone & Utz, p. 100.

- Hone & Utz, p. 101.

- Hone & Utz, p. 109.

- Hone & Utz, p. 106.

- Hone & Utz, p. 107.

- Borneman, p. 258.

- Borneman, p. 239-240.

- Hone & Utz, p. 116.

- Hone & Utz, p. 117.

- Borneman, p. 280.

- "The Vice President's Residence". The White House. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- navy.mil Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Chief of Naval Operations − Responsibilities. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- "10 U.S. Code § 5033 - Chief of Naval Operations: general duties". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "10 U.S. Code § 5031 - Office of the Chief of Naval Operations: function; composition". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "10 U.S. Code § 5032 - Office of the Chief of Naval Operations: general duties". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "10 U.S. Code § 8036 - Deputy Chiefs of Naval Operations". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Swartz, p. 51.

- "Biography - Andrew S. Haeuptle" (PDF). U.S. Navy. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- "Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships". Google Books. 1959. p. 563.

Non-footnotes

- Relieved by Secretary Matthews for his role in the Revolt of the Admirals.

- Died in office of a heart attack.

- Relieved by Secretary of Defense McNamara for insubordination during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

- Appointed as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- Served as U.S. Secretary of Energy from 1989 to 1993.

- Resigned due to controversy surrounding the Tailhook scandal.

- Died in office due to suicide by gunshot.

- Served as acting CNO in capacity as Vice Chief of Naval Operations from 16 May 1996 to 2 August 1996.

References

- "Chief of Naval Operations". Lists of Commanding Officers and Senior Officials of the US Navy. Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- Swartz, Peter. "Organizing OPNAV (1970 - 2009)" (PDF). U.S. Navy. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Thomas C. Hone and Curtis A. Utz. "History of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1915-2015" (PDF). Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.'

- Borneman, Walter R. (2012). The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King – The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-09784-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chiefs of Naval Operations. |

- Official website – Chief Naval Operations

- Office of the Chief of Naval Operations organization

_Adm._Mike_Mullen_meets_with_former_Navy_Chiefs_at_a_CNO_Conference_at_the_Pentagon.jpg.webp)

%252C_1902.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_Adm._Gary_Roughead.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_150917-N-AT895-703_(26207156950).jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)