CLODO

Committee for Liquidation or Subversion of Computers (CLODO) (French: Comité Liquidant ou Détournant les Ordinateurs; 'clodo' being a slang word for the homeless) was a French neo-Luddite anarchist organization, active from 1979 until 1983, that primarily targeted computer companies. CLODO initially began centered around anti-nuclear protests against the GOLFECH nuclear reactor construction but later expanded into a decentralized anarchist movement focusing on computer companies.

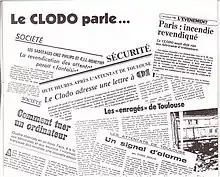

Le Clodo parle (The Clodo speaks) interview from 1983 | |

| Formation | 1979 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1983 |

| Type | |

| Purpose |

|

| Headquarters | Toulouse, France |

Membership | ad hoc, Decentralized affinity group |

CLODO carried out attacks for 4 years primarily in the Toulouse region of France, most notably against U.S. computer manufacturer SPERRY in 1983. As of 1984, CLODO has been classified as inactive by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism and no further activity has since been reported. None of the members of CLODO have been identified.

History

CLODO began in 1979 in protest to the increasing computerized surveillance by national governments and fears of increased oppression as computerization advanced.[1] Those who would eventually form CLODO first united to protest the construction of the GOLFECH nuclear power plant in 1979, during the height of the anti-nuclear movement. Despite efforts to terminate construction on the nuclear power plant, the project continued unabated, prompting CLODO to solidify as an organization and diversify their targets.[2] The first major attack perpetuated by CLODO occurred in 1980, when CLODO carried out arson against the Philips Data System amongst other attacks.[3] CLODO would claim responsibility for multiple sabotages, with others later linked to the organization, and would often employ humorous names and puns when claiming actions.[2] The acronym 'clodo' is a slang term for 'bum' or 'homeless' in French.[2]

In October of 1983, CLODO set fire to the offices of U.S. computer manufacturer SPERRY in protest of Reagan's invasion of Grenada.[2] In total, 7 rooms of the building were damaged and "Reagan attacks Grenada, Sperry a multinational accomplice" was found written inside a vandalized office. The attack was performed in the early morning and no injuries were associated with the event.[4]

In October 1983 following an attack against Sperry-Univac, CLODO sent a manifesto disguised as an interview to the French magazine Processed World. In the manifesto, CLODO rejected the use of computers for the purposes of "surveillance by means of badges and cards, instrument of profit maximization for the bosses and of accelerated pauperization".[2] CLODO additionally stated that, although their future projects were intended to be less spectacular than the firebombing of Sperry-Univac, they planned to carry out actions geared towards an impending telecommunications explosion.[5]

Other attacks

- Between the years 1979 and 1983, CLODO carried out a number of sabotage attacks against companies and government offices involved in the construction of the GOLFECH nuclear power plant.[2]

- In April 1980, CLODO committed arson against Philips Data System's and CII Honeywell Bull's office in Toulouse.[3][6]

- In May 1980, CLODO claimed responsibility for a fire at International Computers Limited.[6]

- In August 1980, CLODO attempted two failed attacks against CII Honeywell Bull in Louveciennes. The first attack failed due to a faulty detonator and the second was diffused prior to detonation.[6]

- In September 1980, CLODO carried out an arson against AP-SOGETI, at the time of SICOB.[6]

- In December 1980, CLODO carried out an arson against Axa's office in the 9th arrondissement of Paris.[6]

- In January 1983, CLODO detonated 3 explosive changes at Computer Center of the Prefecture of Haute-Garonne.[6][3]

- Over the course of several months in 1983, CLODO carried out attacks against Catholic bookstores and religious statues. This included a bust of Pontius Pilate in Lourdes.[2]

- In June 1983, a previously stolen bust of Jean Jaurès, a famous socialist, was found hanging by a noose in front of the city hall in Toulouse, France. The bust was accompanied by a "suicide note" denouncing François Mitterrand for "repressive, authoritarian policies".[2]

- In December 1983, CLODO vandalized the National Cash Register building near Toulouse.[6]

Ideology

CLODO placed emphasis on targeting computer technology and neo-Luddite ideals, but claimed to function as an ad hoc group with no formal organization or leadership.[7][2] CLODO considered themselves “the visible tip of the iceberg”, citing increasing public distrust in computer software and increased worried about the potential implications technology had on limiting people's freedoms. This, more specifically, centered around the fears of government oppression and increased surveillance as computers became more ubiquitous.[1] CLODO's neo-luddite beliefs have been compared to the 1980 writings of Douglas Hofstadter, in which he echoed similar concerns about the “subcognition” of rapidly advancing` technology.[8][9] In 1980, after a series of attacks in the Toulouse area, CLODO released a statement to the French media in which they explained their motives. It read,[10]

"We are workers in the field of dp (data processing) and consequently well place to know the current and future dangers of dp and telecommunications. The computer is the favorite tool of the dominant. It is used to exploit, to put on file, to control, and to repress."

At the time of the Toulouse attacks in 1980, French police were convinced that CLODO was simply an outgrowth of Action Directe, a libertarian communist group. This was later corrected following analysis by National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, who concluded "Although no proof has ever been established that CLODO was affiliated with Action Directe, it seems likely that they had some linkages, but that CLODO was focused more on an anarchist worldview, as opposed to a Marxist-Leninist philosophy."[11] The attacks happened in a wider context of similar attacks throughout Toulouse at the same time.[12]

Legacy

While CLODO's actions never achieved major political victory, their actions raised awareness that European computers were vulnerable to attack. CLODO's attacks, along with other contemporary anarchist groups, prompted the Swedish Defense Ministry to recommend new guidelines around monitoring computer security.[1]

Since 1984, CLODO has no longer been classified as 'active' by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism.[11] None of the members of CLODO have been identified.[13]

A 2022 experimental documentary named 'Machines in Flames' helped spark renewed interest in the group.[14]

References

- Littleton, Matthew J. (1995-11-30). "Information Age Terrorism: Toward Cyberterror - Chapter 4: Shift toward information warfare across the conflict spectrum". Homeland Security Digital Library. Naval Postgraduate School (U.S.).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "CLODO Speaks". www.processedworld.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- "The conditions of operation, intervention and coordination of the police and security services engaged in the fight against terrorism , report of the senatorial commission of inquiry". archive.wikiwix.com. May 17, 1984. p. 23. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- "Grenada News Briefs". UPI. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- Holz, Maxine (February 1984). "CLODO Speaks: Interview with French saboteurs". Processed World. No. 10. San Francisco, California, USA. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- Raufer, Xavier. "ATTENTATS DU GROUPE CLODO". www.xavier-raufer.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- Scritch, Da (2016-09-29). "Ex0036 C.L.O.D.O. et autres néo-luddites". cpu.dascritch.net (in French). Archived from the original on 2022-02-14. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- Stadler, Max (2017). Man not a machine: Models, minds, and mental labor, c.1980. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 233. pp. 73–100. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2017.03.001. ISSN 1875-7855. PMID 28826515.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Vital Models: The Making and Use of Models in the Brain Sciences. Academic Press. 2017-08-15. ISBN 978-0-12-812558-8.

- "CLODO Communique following attack on Colomiers (FR) data-processing centre (1983)". The Anarchist Library. Archived from the original on 2022-01-17.

- "Terrorist Organization Profile: Committee for Liquidation of Computers (CLODO)". MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- raufer, xavier. "ATTACKS COMMITTED BY THE TOULOUSAN ANARCHIST MILIEU (1979-1985)". www.xavier-raufer.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- Cadot, Julien (2017-11-16). "Club Internet #5 : où l'on envisage de détruire les ordinateurs". Numerama (in French). Archived from the original on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- "Machines in Flames". machinesinflames.com. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

External links

- Holz, Maxine (February 1984). "CLODO Speaks: Interview with French saboteurs". Processed World. No. 10. San Francisco, California, USA. Retrieved 25 March 2021. - interview for the Processed World magazine

- Terrorist organization profile - National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism

- The Anarchist Library - Author: C.L.O.D.O