Bukovina Germans

The Bukovina Germans (German: Bukowinadeutsche or Buchenlanddeutsche) are a German ethnic group which settled in Bukovina, a historical region situated at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. Their main demographic presence lasted from the last quarter of the 18th century, when Bukovina was annexed by the Habsburg Empire, until 1940, when nearly all Bukovina Germans (almost 100,000 people)[1] were resettled into the Third Reich as a part of the Heim ins Reich National Socialist population transfer policy.[2][3]

According to the 1910 Imperial Austrian census (which recorded inhabitants by language), the Bukovina Germans represented an ethnic minority accounting for approximately 21.2% of the multi-ethnic population of the Duchy of Bukovina (German: Herzogtum Bukowina).[4] Of those 21.2%, a large proportion was represented by German-speaking Jews.[5] By excluding the Jews, however, the Germans in Bukovina constituted a minority of about 73,000 people (or 9.2%).[6]

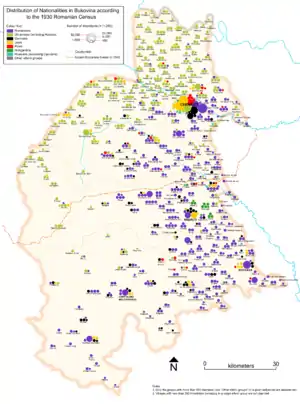

Subsequently, in absolute numbers, 75,533 ethnic Germans (or about 9% of the population) were registered in Bukovina when it was still part of the Kingdom of Romania (as per the Romanian population census of 1930). Historically, some of them developed their own dialect over the course of several hundred years which they called 'Buchenländisch', while others speak a series of other distinct German dialects, depending on their region of origin.[7][8][9][10]

To this day, sparse and very small rural and urban communities of Germans still reside in southern Bukovina (i.e., Suceava County in Romania) and are politically represented by the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania (FDGR/DFDR).[11][12] Lastly, another interesting aspect on the German presence in Bukovina is the fact that the historical/geographic region as a whole has been previously sometimes labeled as 'Switzerland of the East'.[13][14][15]

History

Initial settlement during the Middle Ages (13th century to 14th century)

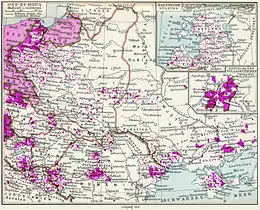

Ethnic Germans known as Transylvanian Saxons (who were mainly craftsmen and merchants stemming from present-day Luxembourg and Rhine-Moselle areas of Western Europe), had sparsely settled in the western mountainous regions of the Principality of Moldavia over the course of the late medieval Ostsiedlung migration (which, in this particular case, took place throughout the 13th and 14th centuries).

These settlers encouraged trade and urban development. Additionally, they founded (and were also briefly in charge under the title of Schultheiß) of some notable medieval settlements such as Baia (German: Stadt Molde or Moldenmarkt), the first capital of the Principality of Moldavia, or Târgu Neamț (German: Niamtz).[16] Subsequently, most of them had been gradually assimilated in these local cultures by the dominant ethnic group of Romanians.

Under the Habsburgs and within the Austrian Empire (1774–1918)

Following the Russo-Turkish War, in 1774–75 the Habsburg monarchy annexed northwestern Moldavia which was predominantly inhabited by Romanians (as many as 85 percent), with smaller numbers of Ukrainians (including Hutsuls and Ruthenians), Armenians, Poles, and Jews.[17]

Since then, the region has been known as Bukovina (German: Bukowina or Buchenland). From 1774 to 1786, the settlement of German craftsmen and farmers in existing villages increased.[18] The settlers included Zipser Germans from the Zips region of Upper Hungary (today mostly Slovakia), Banat Swabians from Banat, and ethnic Germans from Galicia (more specifically Evangelical Lutheran Protestants), but also immigrants from the Rhenish Palatinate, the Baden and Hesse principalities, as well as from impoverished regions of the Bohemian Forest (German: Böhmerwald).[19][20]

Thus, four distinct German linguistic groups were represented as follows:

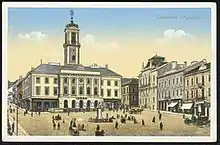

- Austrian High German (Österreichisches Hochdeutsch) was spoken in urban centres like Cernăuți (Czernowitz), Rădăuți (Radautz), Suceava (Suczawa), Gura Humorului (Gura Humora), Câmpulung (Kimpolung), and Siret (Sereth);

- Bohemian-Bavarian German (Deutschböhmisch or Böhmerwäldisch) was spoken by woodsmen in Huta Veche (Althütte), Crăsnișoara Nouă (Neuhütte), Gura Putnei (Karlsberg), Voievodeasa (Fürstenthal), Vadu Negrilesei (Schwarzthal), Poiana Micului (Buchenhain), Dealu Ederii (Lichtenberg), Bori (early colony in Gura Humorului), and Clit (Glitt);[21]

- Palatine Rhine Franconian (Pfälzisch) and Swabian German (Schwäbisch) was spoken in farming villages like Arbore (Arbora), Bădeuți (Deutsch Badeutz), Frătăuții Vechi (Alt Fratautz), Frătăuții Noi (Neu Fratautz), Ilișești (Illischestie), Ițcani (Itzkany), Satu Mare (Deutsch Satulmare) and Tereblestie;[22][23]

- Zipser German (Zipserisch) was spoken by mine workers and their descendants in Cârlibaba (Mariensee or Ludwigsdorf), Iacobeni (Jakobeny), Stulpicani (Stulpikany), and elsewhere.[24]

During the 19th century, the developing German middle class comprised much of the intellectual and political elite of the region; the language of official business and education was predominantly German, particularly among the upper classes. Population growth and a shortage of land led to the establishment of daughter settlements in Galicia, Bessarabia, and Dobruja.

After 1840, a shortage of land caused the decline into poverty of the German rural lower classes; in the late 19th century parts of the German rural population alongside a few Romanians emigrated to the Americas, mainly to the United States (most notably to Ellis and Hays, both located in Kansas) but also to Canada.[25][26][27][28]

Between 1849 and 1851, and from 1863 to 1918, the Duchy of Bukovina became an independent crown land within the Austrian Empire (see also: Cisleithania). However, at this time, in comparison with other Austrian crown lands, Bukovina remained a relatively underdeveloped region on the periphery of the realm, primarily supplying raw materials. This did not prevent it from being called '[the] Switzerland of the Orient' (i.e., of Eastern Europe) or 'Europe in miniature', due to its ethnic and cultural diversity spread over such a small territory.[29]

The Franz-Josephs-Universität (Francisco-Josephina) in Cernăuți (Czernowitz) was founded in 1875, then the easternmost German-speaking university.[30][31] In 1910–11, the Bukovinian Reconciliation (a political agreement between the peoples of Bukovina and their political representatives in the Landtag assembly on the question of autonomous regional administration) took place between the representatives of the nationalities. During the first round of the 20th century, local German-language literature flourished through the writings of Rose Ausländer, Alfred Kittner, Alfred Margul Sperber, or Paul Celan.[32][33][34] Other notable German writers of Bukovina include mixed Ukrainian-German intellectuals Ludwig Adolf Staufe-Simiginowicz and Olha Kobylianska (who was also remotely related to renowned German poet Zacharias Werner).

Early 20th century and Kingdom of Romania (1918–1939)

From 1918 to 1919, following the end of World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bukovina became part of the Kingdom of Romania. At the General Congress of Bukovina held on November 28, 1918,[35] the political representatives of the Bukovina Germans voted and supported the union of Bukovina with the Romanian kingdom, alongside the Romanian and Polish representatives.

From 1933 up until 1940, some German societies and organizations opposed the propaganda of the Third Reich and the National Socialist-aligned so-called 'Reformation Movement'. Beginning in 1938 however, due to the poor economic situation and powerful National Socialist propaganda, a pro-Third Reich mentality developed within the Bukovina German community. Because of this, many increased their preparedness for evacuation.

Outbreak of World War II and Heim ins Reich (1939–1941)

When Nazi Germany signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Soviet Union in 1939 (just before the outbreak of World War II), the fate (unknown to those affected) of the Germans in Bukovina was sealed. In a secret supplementary protocol, it was agreed (among other points) that the northern part of Bukovina would be annexed by the Soviet Union under a territorial re-organization in Central-Eastern Europe, with the German sub-populations therein undergoing compulsory resettlement to other future Nazi-occupied territories.[36] Under this military partitive accord, the Soviet Union occupied northern Romania in 1940.

Consequently, the Third Reich resettled nearly the entire German population of Bukovina (about 96,000 ethnic Germans) to, most notably, Nazi-occupied Poland, where the incoming evacuees were frequently compensated with expropriated farms.[37] From 1941 to 1944, Bukovina was almost entirely Romanian-populated. Additionally, most of the Jewish population (c. 30% of the regional population as a whole) were murdered by the Third Reich in collaboration with fascist Romania under Marshal Ion Antonescu during the Holocaust.

Resettlement in the wake of World War II (1945–1947)

In 1944–45, as the Russian front moved closer, the Bukovina Germans settled in Polish areas (like the remaining German population), fled westward or wherever they could manage. Some remained in East Germany; others went to Austria. In 1945, the 7,500 or so remaining Germans in Bukovina were evacuated to Germany, ending (except for a relatively feeble number of individuals) a significant German presence in Bukovina, Romania after 1940.

During the postwar era, the Bukovina Germans, as other 'homeland refugees', assimilated into the Federal Republic, Austria, or the German Democratic Republic (German: Deutsche Demokratische Republik).[38] Nonetheless, small numbers of ethnic Germans (along with their families) returned to Romania after the resettlement plan failed, most notably the Zipser Germans, but also some Bukovina Germans.[39][40][41][42]

After World War II and life under Communist Romania (1945–1989)

After the end of World War II, the German community of Bukovina declined dramatically in numbers, with only several thousand ethnic Germans still residing in Suceava County (German: Kreis Suczawa) and a few waves of returning expelled Bukovina Germans re-settling the county. As with the rest of the German community in Bukovina, they were constantly harassed by and under the surveillance of the Securitatea, the secret police in Communist Romania, as recorded for the first time in their logs in October 1956.[43]

The documents of the Romanian Communist secret police showcase the fact that many remaining Bukovina Germans expressed their interest to flee the country and immigrate to West Germany. Furthermore, only a few of them had been suspected on the grounds of anti-national sentiment alongside some Ukrainians, as shown by the same reports of the Communist Romanian secret police. In the meantime, mixed Romanian-German families formed in this part of Romania as well, as they have formed prior to the end of World War II and the rise of Communism as well.

In contemporary Romania (1989–present)

During the early 21st century, the German community of Bukovina had dwindled dramatically and is currently on the verge of extinction.[44][45] Nowadays, according to an estimate, the German community in Suceava County represents 0.3% of the total population of the county.[46] Nevertheless, the local branches of FDGR/DFDR in Suceava County are still functional and many local German culture-based festivals (akin to Haferland week of the Transylvanian Saxons) have been held thus far, with numerous members of the Bukovina German diaspora returning home on their occasion, especially in the town of Suceava (German: Suczawa).[47] Furthermore, Germany is also the second most important economic partner and foreign investor of Suceava County, as reported by the prefect of the county in 2021.[48]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 73,000 | — |

| 1930 | 75,533 | +3.5% |

| 1940 | 100,000 | +32.4% |

| 1956 | 3,981 | −96.0% |

| 1966 | 2,830 | −28.9% |

| 1977 | 2,265 | −20.0% |

| 1992 | 2,376 | +4.9% |

| 2002 | 1,773 | −25.4% |

| 2011 | 717 | −59.6% |

| Austrian and Romanian censuses and estimates. After 1940, statistics refer solely to the extent of present-day Suceava County. Source: [49] | ||

The 1930 Romanian census recorded c. 75,000 ethnic Germans in Bukovina.[50] According to another source, namely an article of the Romanian Academy from 2019, there were c. 76,000 ethnic Germans in Bukovina in 1930 and 44% of them lived in urban settlements.[51] Thus, the Bukovina Germans made up 12.46% of the total population of the interwar Suceava County at that time.

According to the 2011 Romanian census, the German minority in southern Bukovina makes up only 0.11% of the total population (including Zipsers and smaller numbers of Regat Germans in Fălticeni).[52] Consequently, the rural and urban settlements of Suceava County, where small German communities still live to this day, are the following ones (according to the 2011 Romanian census):

- Suceava (German: Suczawa): 0.18%

- Rădăuți (German: Radautz): 0.27%

- Gura Humorului (German: Gura Humora): 0.52%

- Câmpulung Moldovenesc (German: Kimpolung): 0.25%

- Fălticeni (German: Foltischeni): 0.02%

- Mănăstirea Humorului (German: Humora Kloster): 1%

- Vatra Moldoviței (German: Watra): 0.25%

- Cârlibaba (German: Ludwigsdorf/Mariensee): 5.06%

- Solca (German: Solka): 0.63%

- Siret (German: Sereth): 0.42%

- Vatra Dornei (German: Dorna-Watra): 0.23%

Organisations

The political representation of the Bukovina Germans (and of all other German-speaking groups in contemporary Romania) is the DFDR/FDGR (German: Demokratisches Forum der Deutschen in Rumänien, Romanian: Forumul Democrat al Germanilor din România) which has a local branch operating in Suceava County with headquarters in the city of Suceava (German: Suczawa).[53] The regional president of FDGR/DFDR Bucovina/Buchenland is Josef-Otto Exner, who is also in charge of the ACI Bukowina Stiftung, a cultural foundation aiming to enhance ties between Romania and Germany.[54]

After World War II, the Bukovina Germans who settled in West Germany founded the Landsmannschaft der Buchenlanddeutschen im Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Homeland Association of the Bukovina Germans in the Federal Republic of Germany). Others, who decided to settle in Austria, founded the Landsmannschaft der Buchenlanddeutschen in Österreich (Homeland Association of the Bukovina Germans in the Federal Republic of Austria).[55]

Gallery

Notable people

- Elisabeth Axmann, writer

- Olha Kobylianska (partly Bukovina German), writer

- Otto Babiasch, Olympic boxer

- Viktor Pestek, Auschwitz guard who helped a prisoner escape, for which he was executed in 1944

- Alfred Kuzmany, Nazi general

- Eduard Neumann, Luftwaffe officer

- Stefan Baretzki, Auschwitz guard who murdered more than 8,000 people

- Ewald Burian, military officer

- Franz Des Loges, former mayor of Suceava

- Alfred Eisenbeisser, professional footballer

- Stefan Hantel (partly Bukovina German), musician

- Anton Keschmann, politician in the Imperial Austrian Parliament

- Roman Neumayer, inductee into German Ice Hockey Hall of Fame

- George Ostafi, abstract painter

- Francisc Rainer, physiologist and anthropologist

- Ludovic Iosif Urban Rudescu, biologist

- Gregor von Rezzori (partly Bukovina German), writer[56]

- Roman Sondermajer (partly Bukovina German), physician, surgeon, and associate professor

- Constantin Schumacher (partly German), professional footballer

- Ludwig Adolf Staufe-Simiginowicz (partly Bukovina German), poet and educator

- Joseph Weber, Roman Catholic prelate

- Lothar Würzel, journalist, linguist, and politician

- Hugo Weczerka, regional historian

- Erich Beck, researcher and academician, Doctor Honoris Causa of Ștefan cel Mare University of Suceava[57]

See also

References

- Jachomowski, Dirk (1984). Die Umsiedlung der Bessarabien-, Bukowina- und Dobrudschadeutschen (in German). R. Oldenbourg. pp. 88–95. ISBN 9783486524710.

- Allen E. Konrad (March 2012). "Southern Bukovina German Villages – 1940" (PDF). DAI Microfilm T-81; Roll 317; Group 1035; Item VOMI 933; Frames 2448462-2448468. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Țurcaș, Ioan; Lucian, Macarie. "German Language and Culture in Southern Bukovina. The Disappearance of a Cultural Enclave" (PDF). PhD Thesis on the Germans in Bukovina. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Martin Mutschlechner. "The German-Austrians in the Habsburg Monarchy". The World of the Habsburgs. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Martin Mutschlechner. "At the Margins of the Empire: Galicia and Bukovina". The World of the Habsburgs. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Ștefan Purici. "Habsburg Bukovina at the Beginning of the Great War. Loyalism or Irredentism?" (PDF). Ștefan cel Mare University, Suceava. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Oguy Oleksandr Dmytrovyci. "Interferențe lexicale Ucraineano-Româno-Germane în Bucovina la sfârșitul sec. XVIII – începutul sec. XX: (determinarea coeficientului lor)" (PDF). Studia Linguistica. Випуск 5/2011 (in Romanian). Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Interview mit Prof. Dr. Oleksandr Oguy aus Czernowitz an der Interkulturellen Germanistik Göttingen". Seminar für Deutsche Philologie, Universität Göttingen (in German). Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Oleksandr Oguy (2011). "Interkulturelle Diskurskontakte Deutsch vs. Buchenlaendisch - Ukrainisch (bzw. ihr Interferenzgrad) in der Bukowina (1900-1920)". Central and Eastern European Online Library (in German). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Luzian Geier (19 February 2016). "Authentische buchenlanddeutsche Mundartproben". ADZ-Online (in German). Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Forumul regional Bucovina". FDGR.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Forumul Democrat al Germanilor din România. "Raport de activitate al Forumului Democrat al Germanilor din România pe anul 2016" (PDF). www.just.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Sophie A. Welsch (March 1986). "The Bukovina-Germans During the Habsburg Period: Settlement, Ethnic Interaction, Contributions" (PDF). Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Gaëlle Fisher (20 November 2018). "Looking Forwards through the Past: Bukovina's "Return to Europe" after 1989–1991". Lean Library. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- David Rechter (16 October 2008). "Geography is destiny: Region, nation and empire in Habsburg Jewish Bukovina". Taylor & Francis Online. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Hugo Weczerka, Das mittelalterliche und frühneuzeitliche Deutschtum im Fürstentum Moldau, München 1960

- Keith Hitchins. The Romanians 1774-1866. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1996), pp. 226

- Iulian Simbeteanu (12 December 2018). "The Duchy of Bukovina - Demographic change, under Austrian rule". Europe Centenary. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Sophie A. Welsch (March 1986). "The Bukovina-Germans During the Habsburg Period: Settlement, Ethnic Interaction, Contributions" (PDF). Immigrants & Minorities, vol. 5, no. 1. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Consiliul Județean Suceava. "Germanii din Bucovina" (PDF). Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Sophia A. Welisch, PhD. "Faith of our Fathers, Ethos and Popular Religious Practices among the German Catholics of Bukovina in the early Twentieth Century". Bukovina Society of the Americas. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Josef Talsky (3 April 2004). "The Regional Distribution of the Germans in Bukovina". Bukovina Society of the Americas. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Irmgard Hein Ellingson. "Galicia: A Multi-Ethnic Overview and Settlement History with Special Reference to Bukovina" (PDF). Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Willi Kosiul, Die Bukowina und ihre Buchenlanddeutschen (2012, ISBN 3942867095), volume 2

- "Bukovina Society of the Americas Home Page". Bukovinasociety.org. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Bukovina Germans". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Bukovina Immigration to North America". Bukovinasociety.org. Archived from the original on 2012-06-09. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "1789-1850: Nemții noștri bucovineni". Drăgușanul.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Prefectura Suceava. "Minorități din Județul Suceava - Prefectura Judeţului Suceava". Yumpu (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- "1876: Bucovina, între Mesia din Sadagura și Universitatea germană". Drăgușanul.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Geschichte der deutschen Vertriebenen und ihrer Heimat - Die Buchenlanddeutsche". ZgV - Zentrum gegen Vertreibungen (in German). Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Eine Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Literaturen Südosteuropas". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 1 June 1998. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Nikolaus Berwanger – Leben und Schaffen eines Rumäniendeutschen" (PDF). Universität Wien, Diplomarbeit (in German). May 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Petro Rychlo. ""Sprache, du heilige": Sprachreflexionen in der deutschen Dichtung der Bukowina" (PDF). Der literarische Zaunkönig Nr. 3/2018: Forschung und Lehre (in German). Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Irina Livezeanu (2000). Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building & Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930. Cornell University Press. pp. 59–. ISBN 0-8014-8688-2.

- Tiberiu Cosovan (24 February 2016). "Lansarea volumului „Deportarea germanilor bucovineni în Uniunea Sovietică"". Monitorul de Suceava (in Romanian). Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "Comunitatea germană din Mitocu Dragomirnei". Primăria Mitocu Dragomirnei (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Welisch Sophie (1984). "The Second World War resettlement of the Bukovina‐Germans". Immigrants. 3: 49–68. doi:10.1080/02619288.1984.9974569.

- Alfred Wanza (25 October 2019). "Die Geschichte einer Deutschen in der Bukowina". Bukowina Freunde (in German). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Luigi Bărăgoiu. "Nea Adolf din Voievodeasa, botezat în urmă cu 77 de ani de Adolf Hitler". Monitorul de Suceava (in Romanian). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Dănuț Zuzeac (28 January 2018). "Povestea lui 'nea Adolf, românul botezat de Hitler: "Mama a dat foc certificatului meu de naştere de frica ruşilor"". Ziarul Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Sandrinio Neagu (6 August 2016). "Reportaj: Hitler i-a chemat acasă şi sovieticii i-au trimis în Siberia. Povestea neromanţată a etnicilor germani din perioada celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial". Monitorul de Suceava (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Problema „minorităţi etnice" în fondul Documentar Suceava" (PDF). Arhivele CNSAS (in Romanian). 16 October 1956. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Victor Rouă (9 August 2020). "The Bukovina Germans: A Community On The Verge Of Extinction". The Dockyards. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Redacția SV News (4 March 2013). "Numărul etnicilor germani a scăzut cu peste 1.000 în ultimii nouă ani". SV News (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Priest Mihai Cobziuc (19 July 2021). "Comunități etnice din Bucovina – germanii". Arhiepiscopia Sucevei și Rădăuților (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- CJ Suceava. "Germanii din Bucovina" (PDF). Materialele oficiale ale Consiliului Județean Suceava (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Redacția News Bucovina (9 July 2021). "Prefectul de Suceava, Iulian Cimpoeșu, la cea de-a 24-a sesiune a Comisiei guvernamentale româno-germane: Germania se situează pe locul doi, ca investitor în județul Suceava". News Bucovina (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- "Populaţia după etnie la recensămintele din perioada 1930 - 2002, pe judeţe" (PDF) (in Romanian). Institutul Naţional de Statistică. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- Hannelore Baier, Martin Bottesch, u. a.: Geschichte und Traditionen der deutschen Minderheit in Rumänien (Lehrbuch für die 6. und 7. Klasse der Schulen mit deutscher Unterrichtssprache). Mediaș 2007, S. hier 19-36.

- Mathias Beer, Sorin Radu, and Florian Kührer-Wielach (2019). "Germanii din România: Migrație și patrimoniu cultural după 1945" (PDF). Academia Română: Migrații, politici de stat şi identități culturale în spațiul românesc şi european volumul II, coordonator Victor Spinei (in Romanian). Retrieved 19 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rezultatele finale ale Recensământului din 2011: „Tab8. Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Institutul Național de Statistică din România. (July, 2013) - http://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/sR_Tab_8.xls Archived 2016-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Alin Dima (10 August 2015). "Spiritul autentic german a dominat la ceas de sărbătoare Suceava". Crain Nou (in Romanian). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Buchenland". Demokratisches Forum der Deutschen in Rumänien (in German). 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "Landsmannschaft der Buchenlanddeutschen in Österreich". Verband der deutschen altösterreichischen Landsmannschaften in Österreich (VLÖ) (in German). Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Dr. Markus Fischer (14 November 2013). "Gregor von Rezzori auf der Spur". Allgemeine Deutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Mihai Iacobescu. "Erich Beck și Bucovina" (PDF). Atlas USV. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

External links

- Bukovina Society of the Americas

- Das Mädchen aus dem Wald by Claus Stephani

.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)