Barbara Hammer

Barbara Jean Hammer (May 15, 1939 – March 16, 2019) was an American feminist film director, producer, writer, and cinematographer. She is known for being one of the pioneers[1] of lesbian film genre, whose career spanned over 50 years. Hammer is known for having created experimental films dealing with women's issues such as gender roles, lesbian relationships and coping with aging and family. She resided in New York City and Kerhonkson, New York, and taught each summer at the European Graduate School.[2]

Barbara Hammer | |

|---|---|

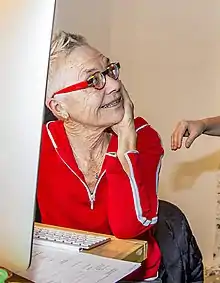

Hammer at the 2014 Art+Feminism Wikipedia Editathon | |

| Born | Barbara Jean Hammer May 15, 1939 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | March 16, 2019 (aged 79) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Filmmaker |

| Years active | 1968–2019 |

| Spouse(s) | Florrie R. Burke |

| Website | Official website |

Life

Hammer was born in Los Angeles and grew up in Inglewood, the daughter of Marian (Kusz) and John Wilber Hammer. She became familiar with the film industry from a young age, as her mother hoped she would become a child star like Shirley Temple, and her grandmother worked as a live-in cook for the American film director D.W. Griffith.[3] Her maternal grandparents were Ukrainian. Her grandfather was from Zbarazh. Hammer was raised without religion, but her grandmother was Roman Catholic.

In 1961, Hammer graduated with a bachelor's degree in psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles and got married to Clayton Ward, on the condition that he take her traveling around the world.[2] She received a master's degree in English literature in 1963.[2] In the early 1970s she studied film at San Francisco State University. This is where she first encountered Maya Deren's Meshes of the Afternoon, which inspired her to make experimental films about her personal life.

In 1974, Hammer was married and teaching at a community college in Santa Rosa, California. Around this time she came out as a lesbian, after talking with another student in a feminist group. After leaving her marriage, she "took off on a motorcycle with a Super-8 camera." That year she filmed Dyketactics, which is widely considered one of the first lesbian films. She graduated with a Masters in film from San Francisco State University.

She released her first feature film, an experimental documentary about the marginalization of LGBT people in the 20th century, Nitrate Kisses in 1992.[2] It was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival. It won the Polar Bear Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Best Documentary Award at the Internacional de Cine Realizado por Mujeres in Madrid. Contrastingly, right-wing organizations labeled the film a “homoerotic film abomination.”[2] She earned a Post Masters in Multi-Media Digital Studies, at the American Film Institute in 1997. In 2000, she received the Moving Image award from Creative Capital and in 2013 she was a Guggenheim Fellow.

She received the first Shirley Clarke Avant-Garde Filmmaker Award in October 2006, the Women In Film Award from the St. Louis International Film Festival in 2006, and in 2009 the Teddy Award for the best short film for her film 'A Horse Is Not A Metaphor' at the Berlin International Film Festival.

In 2010, Hammer published her autobiography, HAMMER! Making Movies Out of Sex and Life, which addresses her personal history and her philosophies on art.

She taught film at The European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland. In 2017, the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University acquired Hammer's archives.

Hammer's film collection, comprising her originals, prints, outtakes, and other material resides at the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles, where a project is in progress to restore her complete film output. As of 2020, the archive has preserved nearly twenty of Hammer's films, including Multiple Orgasm, Sanctus, Menses, and No No Nooky T.V.

After years of short-term relationships, she got married to human rights advocate Florrie Burke until the time of her death, and in 1995 she made a film featuring images of Burke called Tender Fictions.[2] They were partners for thirty-one years.

Career

Hammer's career worked within experimental 16mm film and video spanned 5 decades and her body of work includes almost 100 films.[3] Her early films, made during her time at San Francisco State, depict a distinct Bay Area lesbian experience. Such films embodied the 70s notion of cultural feminism, which led them to be criticized by 3rd wave feminists for not being trans-inclusive.[1] Notable films of her early filmography include: Superdyke, a performative documentary about lesbian militancy,[4][1] Double Strength, a short capturing the highs and lows within a lesbian relationship,[5] and Women I Love, which interweaves fruit imagery with images of her female relationships to create a tantric atmosphere.[6]

Hammer's mid-career films danced between short film and feature length. This part of her career was staged by her decision to move from California to New York, a decision provoked in part by her desire to remove herself from the environment that directed her towards the cultural feminism of her early films that faced such harsh critique.[1] Two important films of this period were Bent Time and Nitrate Kisses. The former bends light within the frame to simulate the theoretical bending of time to explore her decision to relocate to New York City, the place where she remained until her death.[2][3][7] The latter is an unveiling of the marginalization Queer Americans have been subject to since World War 1, and was controversial due to its sex scene featuring older lesbians.[8][3]

Hammer's late career coincides with her rise to public prominence with museum retrospectives and her acquisition of a Guggenheim Fellowship. This section of her body of work focused on the body as it aged, hurt, and moved.[3] This was directly connected to her arduous battle with cancer that began with her diagnosis in 2006.[3] Three emblematic works from this period of her career are Optic Nerve, A Horse is Not a Metaphor, and Evidentiary Bodies. Optic Nerve is a film that uses an optical printer add an additional layer to the film to reflect on her familial relationship to her grandmother and the aging of the body.[9][10][11] A Horse is Not a Metaphor is an autobiographical depiction of Hammer's fight with and the remission of her 3rd stage ovarian cancer.[12] Evidentiary Bodies is her final piece, and it includes a melding of performance, artistic installation, and film, in order to act as a culmination of her involvement with the right to die movement.[3]

Awards

Hammer created more than 80 moving image works throughout her life, and also received a great number of honors.[2]

In 2007, Hammer was honored with an exhibition and tribute in Taipei at the Chinese Cultural University Digital Imaging Center. In New York in 2010, Hammer had a one-month exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art. Additionally, in 2013 she was granted a Guggenheim Fellowship for her film Waking Up Together. She also had exhibitions in London at The Tate Modern in 2012, in Paris at the Jeu de Paume also in 2012, in Toronto for the International Film Festival in 2013 and in Berlin at the Koch Oberhuber Woolfe in both 2011 and 2014.[2]

Hammer received numerous awards during the span of her career. She was chosen by the Whitney Biennial in 1985, 1989, and 1993 for her films Optic Nerve, Endangered and Nitrate Kisses respectively. In 2006, she won both the first ever Shirley Clarke Avant-Garde Filmmaker Award from New York Women in Film and Television as well as the Women in Film Award from the St. Louis International Film Festival.[2]

In 2008, Hammer received The Leo Award from the Flaherty Film Seminar. Her films Generations and Maya Deren's Sink both won the Teddy Award in 2011 for Best Short Films. Her film A Horse Is Not A Metaphor won the Teddy Award for Best Short Film in 2009 it also won Second Prize at the Black Maria Film Festival. It was also selected for several film festivals: the Torino Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Punta de Vista Film Festival, the Festival de Films des Femmes Creteil, and the International Women's Film Festival Dortmund/Koln.[2]

A cumulative list of her acquired awards is available below:

- Stan Brakhage Vision Award, Denver Film Society (2018)

- Temple University Films and Media Arts Tribute Award, Philadelphia, PA (2018)

- Selected Master Filmmaker, Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, Claremont, CA (2018)

- Resisting Paradise, Best Documentary, Memphis Film and Video Festival, Memphis, TN (2018)

- Resisting Paradise, Aesthetic Art Award, Asolo Art Film Festival, Asolo, Italy (2018)

- Resisting Paradise, Southern Circuit Tour (screenings in 7 southern cities) (2018)

- Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Arts, Trinity College (2012)

- The Judy Grahn Award for Lesbian Nonfiction (2011)

- The Publishing Triangle Lambda Award for Best Lesbian Memoir Writing (2011)

- LEO Award for Outstanding Contribution to Film, Flaherty Seminars, Leo Dratfield Endowment and International Film Seminars (2008)

- Platinum Tribute, Outfest (2007)

- Shirley Clarke Avant-Garde Film Award, St. Louis International Film Festival, NYWFT (2006)

- Fulbright Senior Specialist, Academy of Fine Arts and Design Batislava, Slovakiav (2005)

- Selected Master Filmmaker, Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, Claremont, CA (2005)

- Resisting Paradise, Southern Circuit Travel Award (2004)

- History Lessons, Documentary Award, Athens International Film/Video Festival (2003)

- Resisting Paradise, Close-up: Visionaries of Modern Cinema Award, Frameline (2003)

- Peace Prize, 1st Global Peace Film Festival (2003)

- Tribute, U.S.A. Film Festival (2003)

- Career Honor from Mayor of Philadelphia, International Gay-Lesbian Film Festival (2001)

- Frameline Award, Career Honor, Frameline International Film Festival (2000)

- Devotion, Jurors’ Merit Award, Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival (2000)

- Tender Fictions, Awarded Best Documentary Cash Prize, Immaginaria Festival (1998)

- Tender Fictions, Documentary Competition, Yamagata International Doc Film Festival (1997)

- Tender Fictions, Director's Choice, Charlotte Film Festival (1996)

- Documentary Competition, Sundance Film Festival (1996)

- The Forum, Berlin International Film Festival (1996)

- Isabel Liddell Art Award, Ann Arbor Film Festival (1996)

- Cineprobe, Museum of Modern Art, NYC (1995)

- Nitrate Kisses, Audience Award for Best Documentary, International Festival of Women Directors (1994)

- Polar Bear Award for Lifetime Contribution to Lesbian/Gay Cinema, Berlin International Film Festival (1993)

- Cineprobe, Museum of Modern Art, NYC (1993)

- Vital Signs, Excellence Award, California State Fair (1992)

- Best Experimental Film, Utah Film Festival (1992)

- Juror's Award, Black Maria Film Festival (1992)

- Society for the Encouragement of Contemporary Art Video Award (1992)

- The John D. Phelan Award in Video (1991)

- Sanctus, Special Award, Ann Arbor Film Festival (1991)

- Second Prize, Experimental Film, Baltimore Film Festival (1991)

- Endangered, First Prize, Atlanta Film Festival (1991)

- First Prize, Black Maria Film Festival (1991)

- First Prize, Buck's County Film Festival (1991)

- The Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial (1991)

- Cineprobe, Museum of Modern Art, NYC (1991)

- The Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial (1989)

- Endangered & Optic Nerve (1988)

- The John D. Phelan Award in Film (1988)

- Place Mattes, First Prize Animation, Marin Country Film Festival (1988)

- No No Nooky T.V., Second Prize, Ann Arbor Film Festival (1987)

- First Prize, Humboldt Film Festival (1987)

- Optic Nerve, First Prize, Ann Arbor Film Festival (1986)

- First Prize, Onion City Film Festival (1986)

- Optic Nerve, Cineprobe, Museum of Modern Art, NYC (1985)

- The Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial (1985)

Style and reception

Hammer was an avant-garde filmmaker and focused a large sum of her films on feminist or lesbian topics. Through the use of experimental cinema, Hammer exposed her audiences to feminist theory. Her films, she said, are meant to promote “independence and freedom from social restriction.” [13]

Her films were regarded as being controversial because they focused on feminine taboo topics such as menstruation, the orgasm from the female perspective, and lesbianism. Hammer experimented with different film gauges in the 1980s, especially with 16mm film. She did this in order to show just how fragile film itself is.[2] One of her most well-known films, Nitrate Kisses, “explores three deviant sexualities–S/M lesbianism, mixed-race gay male lovemaking, and the passions and sexual practices of older lesbians.”[14]

Hammer's film Dyketactics (1974) illustrates the importance of the female body to her work, and is shot in two sequences. In the first sequence, the film depicts a group of nude women gathering in the countryside to dance, bathe, touch one another, and interact with the environment. In the second sequence, Hammer herself is filmed sharing an intimate moment with another woman within a Bay Area house. Between the two sequences, Hammer aimed to create an erotic film that used different film language than the mainstream, heterosexual erotic films of the time.[15] She called it a "lesbian commercial".[16]

Hammer's early films utilized natural imagery, such as trees and fruit, to be associated with the female body.[15] Nitrate Kisses (1992) was her longest film to date when it was completed. The film comments on how members of the LGBT community are often left out of history and simultaneously works to remedy the problem by offering some of this lost history to its viewers.[17][18]

This style of filmmaking was met with mixed reactions. In a review of Hammer's films Women I Love (1976) and Double Strength (1978), critic Andrea Weiss noted, "It's become fashionable for women's bodies to be represented by pieces of fruit," and criticized Hammer for "adopting the masculine romanticized view of women.".[19] According to Michael Schell "her relentless pursuit of an artistic vision, informed by the American tradition of experimental cinema, whose integrity was personal, not simply political, can pose a challenge to the assumptions of both sub- and mainstream cultures".[18]

Grants

In 2017, the first Barbara Hammer Lesbian Experimental Filmmaking Grant was awarded, to Fair Brane.[20]

The SFSU Queer Cinema Project supports Queer filmmakers through the annual Barbara Hammer Awards for SFSU students by granting two students funding towards the completion of a Queer focused project.[2]

In 2020, Filmmaker Lynne Sachs created the Ann Arbor Festival award for the creation of a film that best conveys Hammer's celebration of female experience.[2]

Feminist and lesbian works impact

Through her controversial work, Hammer is considered as a pioneer of queer cinema.[2] Her goal through her film work was to provoke discourse on those who are marginalized, and more specifically, lesbians who are marginalized. She felt that making films that show her personal experience renaming herself as lesbian will help start the conversation on lesbianism and get people to stop ignoring its existence.[21]

Illness, right to die activism, and death

In 2006, Hammer was diagnosed with stage 3 ovarian cancer. After 12 years of chemotherapy, she fought for the right of self-euthanasia. She referenced this in her works, such as her 2009 film A Horse is Not a Metaphor, in which she expressed the ups and downs of a cancer patient. Through her experience, she became an advocate for Right to Die and fought for the New York Medical Aid in Dying Act.[22]

On October 10, 2018, Hammer presented "The Art of Dying," a performative lecture at the Whitney Museum of Art.[23]

Hammer died from endometrioid ovarian cancer on March 16, 2019, at the age of 79. She had been receiving palliative hospice care at the time of her death.[23][24][25]

Filmography

- Contribution to Light (1968)

- The Baptism (1968)

- White Cassandra (1968)

- Schizy (1968)

- Clay I Love You II (1968–69)

- Aldebaran Sees (1969)

- Barbara Ward Will Never Die (1969)

- Cleansed II (1969)

- Death of a Marriage (1969)

- Elegy (1970)

- Play or ‘Yes’, ‘Yes’, Yes’ (1970)

- Traveling: Marie and Me (1970)

- The Song of the Clinking Cup (1972)

- I Was/I Am (1973)

- Sisters! (1974)

- A Gay Day (1973)

- Yellow Hammer (1973)

- Dyketactics (1974)

- X (1974)

- Women's Rites, or Truth is the Daughter of Time (1974)

- Menses (1974)

- Jane Brakhage (1975)

- Superdyke (1975)

- Psychosynthesis (1975)

- Superdyke Meets Madame X (1975)

- San Diego Women's Music Festival (1975)

- Guatemala Weave (1975)

- Moon Goddess (1975) – with G. Churchman

- Eggs (1972)

- Multiple Orgasm (1976)

- Women I Love (1976)

- Stress Scars and Pleasure Wrinkles (1976)

- The Great Goddess (1977)

- Double Strength (1978)

- Home (1978)

- Haircut (1978)

- Available Space (1978)

- Sappho (1978)

- Dream Age (1979)

- Take Back the Night March on Broadway 1979 (1979)

- Our Trip (1980)

- Lesbian Humor: Collection of short films (1980–1987)

- Pictures for Barbara (1980)

- Machu Picchu (1980)

- Natura Erotica (1980)

- See What You Hear What You See (1980)

- Our Trip (1981)

- Arequipa (1981)

- Pools (1981) – with B. Klutinis

- Synch-Touch (1981)

- The Lesbos Film (1981)

- Pond and Waterfall (1982)

- Audience (1983)

- See What You Hear What You See (1983)

- Stone Circles (1983)

- New York Loft (1983)

- Bamboo Xerox (1984)

- Pearl Diver (1984)

- Bent Time (1984)

- Doll House (1984)

- Parisian Blinds (1984)

- Tourist (1984–85)

- Optic Nerve (1985)

- Hot Flash (1985)

- Would You Like to Meet Your Neighbor? A New York Subway *Tape(1985)

- Bedtime Stories (1986)

- The History of the World According to a Lesbian (1986)

- Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of AIDS (1986)

- No No Nooky T.V. (1987)

- Place Mattes (1987)

- Endangered (1988)

- Drive, She Said (1988)

- Two Bad Daughters (1988)[28]

- Still Point (1989)

- T.V. Tart (1989)[28]

- Sanctus (1990)

- Vital Signs (1991)

- Dr. Watson's X-Rays (1991)

- Nitrate Kisses (1992)

- Save Sex (1993)

- Shirley Temple and me (1993)*Out in South Africa (1994)

- Tender Fictions (1996)

- The Female Closet (1997)

- Blue Film No.6: Love is Where You Find It (1998)

- Devotion: A Film About Ogawa Productions (2000)

- History Lessons (2000)[28]

- My Babushka: Searching Ukrainian Identities (2001)

- Our Grief is Not a Cry for War (2001)

- Resisting Paradise (2003)

- Love/Other (2005)

- Dying Women of Jeju-Do (2007)

- Fucking Different New York (2007) (segment "Villa Serbolloni")

- A Horse is not a Metaphor (2009) (Teddy Award)

- Generations (2010)

- Maya Deren's Sink (2011)

- Welcome to this House (2015)

- Lesbian Whale (2015)

- Evidentiary Bodies (2018)

Retrospectives

- La Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona (9 June 2020 – October 18, 2020)

- “Barbara Hammer: In This Body,” Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University (2019)

- Color Me Barbara, Retrospective at NewsFest, New York (2019)

- Museum of the Moving Image, Queens (2019)

- Austrian Film Museum, Vienna (2018)

- Whitney Museum of Art, New York City (October 10, 2018)

- Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, New York City (2017)

- National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (2015)

- Kunsthall Oslo, Norway (2013)

- Toronto International Film Festival Cinematheque Free Screen (Winter 2013)

- Jeu de paume, Paris (June 12 – July 1, 2012)

- Tate Modern, London (February 3 – 26, 2012)

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City (September 15 – October 13, 2010)

- XII Muestra Internacional de Cine Realizado por Mujeres, Zaragosa, Spain (2009)

- Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain (2008)

- Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan (2007)

- Turin International Gay & Lesbian Film Festival, Italy (2006)

- Mar del Plata International Film Festival, Mar del Plata, Argentina (2005)

- Irish Film Centre, Dublin, Ireland (2004)

- Australia Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Australia (2003)

- Seoul Art Cinema, Korea (2002)

- Women Make Waves Film/Video Festival, Taipei, Taiwan (2002)

- Women Make Waves Film/Video Festival, Taipei, Taiwan (2000)

- Immaginaria, 6th Women's Film Festival, Bologna, Italy (1998)

- yyz Gallery, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1997)

- Out in South Africa Film Festival, Johannesburg/Capetown, South Africa (1994)

- Film Forum, Director's Guild of America, LA, CA (1993)

- Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska, Lincoln NE (1993)

- Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, Univ. of Nebraska, Lincoln (1992)

- Retrospective: Film Forum, Directors Guild of America, Los Angeles (1991)

- Panorama, The Berlin International Film Festival, Berlin, Germany (1986)

- Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France (1985)

See also

References

- Youmans, Greg (2012). "Performing Essentialism: Reassessing Barbara Hammer's Films of the 1970s" (PDF). Camera Obscura. 27 (3): 100–135. doi:10.1215/02705346-1727473.

- "Barbara Hammer-Biography". barbarahammer.com.

- White, Patricia (December 1, 2021). "Introduction: Late Hammer". Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies. 36 (3): 84–87. doi:10.1215/02705346-9349371. ISSN 0270-5346. S2CID 244534382.

- "UbuWeb Film & Video: Barbara Hammer - Superdyke (1975)". ubu.com. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "UbuWeb Film & Video: Barbara Hammer - Double Strength (1978)". ubu.com. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- "UbuWeb Film & Video: Barbara Hammer - Women I Love (1976)". ubu.com. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- "BENT TIME". Barbara Hammer. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "UbuWeb Film & Video: Barbara Hammer - Nitrate Kisses (1992)". ubu.com. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- "OPTIC NERVE". Barbara Hammer. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- "UbuWeb Film & Video: Barbara Hammer - Optic Nerve (1985)". ubu.com. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- Osterweil, Ara (April 9, 2010). "A Body Is Not a Metaphor: Barbara Hammer's X-Ray Vision". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 14 (2–3): 185–200. doi:10.1080/10894160903196533. ISSN 1089-4160. PMID 20408011. S2CID 6728666.

- "UbuWeb Film & Video: Barbara Hammer - A Horse Is Not A Metaphor (2008)". ubu.com. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- Harper, Glenn (April 1998). Interventions and Provocations: Conversations on Art, Culture, and Resistance. discoverE: SUNY Press. pp. 147–159. ISBN 0-7914-3726-4.

- Juhasz, Alexandra (2001). Women of Vision: Histories in Feminist Film and Video. Vol. 9 (NED - New ed.). JSTOR: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 77–91. ISBN 9780816633715. JSTOR 10.5749/j.cttts8r3.

- Youmans, Greg (September 2012). "Performing Essentialism: Reassessing Barbara Hammer's Films of the 1970s". Camera Obscura. 27 (3): 101–135. doi:10.1215/02705346-1727473.

- Radical light : alternative film & video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-2000. Anker, Steve, 1949-, Geritz, Kathy, 1957-, Seid, Steve. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2010. p. 195. ISBN 9780520249103. OCLC 606760462.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Willis, Holly; Hammer, Barbara (1994). "Uncommon History: An Interview with Barbara Hammer". Film Quarterly. 47 (4): 7–13. doi:10.2307/1212978. JSTOR 1212978.

- Schell, Michael. "Barbara Hammer remembered in Seattle". Schellsburg. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- Weiss, Andrea (1981). "Women I Love, Double Strength: Lesbian Cinema and Romantic Love". Jump Cut.

- Durón, Maximilíano (December 5, 2017). "Queer-Art Names Inaugural Recipient of Barbara Hammer Lesbian Experimental Filmmaking Grant".

- Harper, Glenn (1998). Interventions and Provocations: Conversations on Art, Culture, and Resistance. discoverE: SUNY Press. pp. 147–159. ISBN 0-7914-3726-4.

- "Right To Die Advocate: 'Living Has Been Terrific' But Now She Wants Control Over When It Ends". February 6, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Whitney Museum of American Art (October 18, 2018), The Art of Dying or (Palliative Art Making in the Age of Anxiety) | Live from the Whitney, retrieved March 13, 2019

- Greenberger, Maximilíano Durón and Alex (March 16, 2019). "Barbara Hammer, Pioneering Queer Experimental Filmmaker, Dead at 79".

- Richard Sandomir (March 20, 2019). "Barbara Hammer, Filmmaker of Lesbian Sexuality Dies at 79". The New York Times. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

Further reading

- Kleinhans, Chuck (2007). "Barbara Hammer: Lyrics and History". In Robin Blaetz (ed.). Women's Experimental Cinema. Duke University Press.

- Epstein, Sonia (2016). "Barbara Hammer and the X-rays of James Sibley Watson." Sloan Science & Film.

- Alexandra Juhasz, editor (2001). Women of Vision: Histories in Feminist Film and Video. University of Minnesota Press.

- White, Patricia (December 1, 2021). "Introduction: Late Hammer". In Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies. 36 (3): 84–87. doi:10.1215/02705346-9349371. ISSN 0270-5346.

- Osterweil, Ara (April 9, 2010). "A Body Is Not a Metaphor: Barbara Hammer's X-Ray Vision". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 14 (2–3): 185–200. doi:10.1080/10894160903196533. ISSN 1089-4160. PMID 20408011.

External links

- Official Website

- Barbara Hammer at IMDb

- Barbara Hammer at UbuWeb Experimental Film Archive

- Barbara Hammer at Women Make Movies website

- Barbara Hammer in the collection of MoMA

- "Barbara Hammer's Exit Interview," Masha Gessen, New Yorker, February 24, 2019.

- Barbara Hammer Papers. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.