Self-cannibalism

Self-cannibalism is the practice of eating oneself, also called autocannibalism,[1] or autosarcophagy.[2] A similar term which is applied differently is autophagy, which specifically denotes the normal process of self-degradation by cells. While almost an exclusive term for this process, autophagy nonetheless has occasionally made its way into more common usage.[3]

Among humans

As a natural occurrence

A certain amount of self-cannibalism occurs unknowingly, as the body consumes dead cells from the tongue and cheeks.

As a disorder or symptom thereof

Fingernail-biting that develops into fingernail-eating is a form of pica. Other forms of pica include dermatophagia,[4] and compulsion of eating one's own hair, which can form a hairball in the stomach. Left untreated, this can cause death due to excessive hair buildup.[5]

Self-cannibalism can be a form of self harm and a symptom of mental illnesses such as personality disorders, psychosis, or drug addiction.[6]

As a choice

Some people will engage in self-cannibalism as an extreme form of body modification, for example ingesting their own blood or skin.[3] Others will drink their own blood, a practice called autovampirism,[7] but sucking blood from wounds is generally not considered cannibalism. Placentophagy may be a form of self-cannibalism.

As a crime

Forced self-cannibalism as a form of torture or war crime has been reported. Erzsébet Báthory allegedly forced some of her servants to eat their own flesh in the early 17th century.[8] Incidents were reported in the years following the 1991 Haitian coup d'état.[9] In the 1990s, young people in Sudan were forced to eat their own ears.[10]

Among animals

The short-tailed cricket is known to eat its own wings.[11] There is evidence of certain animals digesting their own nervous tissue when they transition to a new phase of life. The sea squirt (with a tadpole-like shape) contains a ganglion "brain" in its head, which it digests after attaching itself to a rock and becoming stationary, forming an anemone-like organism. This has been used as evidence that the purpose of brain and nervous tissue is primarily to produce movement. Self-cannibalism behavior has been documented in North American rat snakes: one captive snake attempted to consume itself twice, dying in the second attempt. Another wild rat snake was found having swallowed about two-thirds of its body.[12]

References in myth and legend

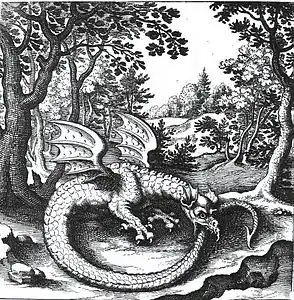

The ancient symbol Ouroboros depicts a serpent biting its own tail.

Erysichthon from Greek mythology ate himself in insatiable hunger given him, as a punishment, by Demeter.

In an Arthurian tale, King Agrestes of Camelot goes mad after massacring the Christian disciples of Josephus within his city, and eats his own hands.

Notes

- "Man-eaters: The Evidence for Coastal Tupi Cannibalism" mei(sh) dot org

- Mikellides AP (October 1950). "Two cases of self-cannibalism (autosarcophagy)". Cyprus Med J. 3 (12): 498–500. PMID 14849189.

- Benecke, Mark "First report of non-psychotic self-cannibalism (autophagy), tongue splicing and scar patterns (scarification) as an extreme form of cultural body modification in a Western civilization"

- Hayden, Danielle (5 November 2018). "What to Know About Dermatophagia, the 'Skin-Eating' Disorder That Causes Me to Gnaw at My Own Fingers".

- Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH (2008). "Trichotillomania" (PDF). Dermatol Ther. 21 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00165.x. PMID 18318881.

- Yilmaz, Atakan; Uyanik, Emrah; Şengül, Melike C. Balci; Yaylaci, Serpil; Karcioglu, Ozgur; Serinken, Mustafa (August 2014). "Self-Cannibalism: The Man Who Eats Himself". The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 15 (6): 701–2. doi:10.5811/westjem.2014.6.22705. PMC 4162732. PMID 25247046.

- NCBI PubMed

- Adams, Cecil "Did Dracula really exist?" The Straight Dope

- Chin, Pat. "Behind the Rockwood case" Workers World, April 6, 1996

- Lambeth Daily News 6 August 1998

- Taber, Stephen Welton (2005) Invertebrates Of Central Texas Wetlands, page 200.

- Mattison, Chris (2007). The New Encyclopedia of Snakes. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-691-13295-2.