Artemy Vedel

Artemy Lukyanovich Vedel (Russian: Артемий Лукьянович Ведель, Ukrainian: Артем Лук'янович Ведель; 13 April 1767 – 26 July 1808), born Artemy Lukyanovich Vedelsky, was a Ukrainian-born Russian Imperial[1][2][3][4][5] composer of military and liturgical music, who made an important contribution in the music history of Ukraine. Together with Maxim Berezovsky and Dmitry Bortniansky, Vedel is recognized as one of the 'Golden Three' composers of 18th century Ukrainian classical music, and one of Russia's greatest choral composers.

Vedel was born in Kyiv, Russian Empire, the son of a wealthy wood carver. He studied at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy until 1787, after which he was appointed to conduct the academy’s choir and orchestra. In 1788 he was sent to Moscow to serve as the assistant choir master for the regional governor, but he returned home (1791) and resumed his career at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. General of the Imperial Russian Army Andrei Levanidov acquired his services to lead the city's regimental chapel and choir—under Levanidov’s patronage, Vedel reached the peak of his creativity as a composer. He moved with Levanidov to the Kharkov Governorate (now Kharkiv, Ukraine), where he helped to organize a new choir and orchestra, and taught as Kapellmeister at the Kharkiv Collegium.

In 1799 Vedel was summoned to St. Petersburg on suspicion of participating in a conspiracy against the Emperor Paul I; after that Vedel's works in churches were banned. Left without a patron, he returned to home to Kyiv. In 1799 he became a novice monk of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra. The monastery authorities discovered handwritten threats about the Russian royal family, and accused Vedel of writing them. He was incarcerated for life as a mental patient, and forbidden to compose. After almost a decade in a Kyiv lunatic asylum, he was allowed by the authorities to return to his father's house to die.

Vedel's music was censored by the authorities in the Imperial Russia (and later by the Soviet Union). More than 80 of his works are known, including 31 choral concertos, but many of his compositions have been lost. The single autograph score by Vedel to have survived includes his Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom; most of his choral music, however, uses texts taken from the Psalms. The style of his compositions reflects the changes taking place in classical music during his lifetime; he was influenced by the Ukrainian baroque traditions, but was also by new West European (in particular Italian) operatic and instrumental styles.

Background

Choral music has a special significance for Ukrainian culture; according to the musicologist Yurii Chekan, "choral music embodies Ukrainian national mentality, and the soul of the people".[6]

The character of Russian and Ukrainian worship derives from performances of the znamenny chant, which developed a tradition that was characterised by seamless lines and a capacity to sustain pitch. The tradition reached its culmination during the 16th and 17th centuries, having taken on its own character in the Russian Empire some three centuries earlier.[7]

The choral music of Ukraine changed during the Baroque era; passion and emotion, contrasting dynamics, timbre and musical texture were introduced, and monody was replaced by polyphony. The new polychoral culture became known as the partesnyy (‘singing in parts’) style.[6] During the 19th century, Znamenny chants were gradually superseded by newer ones, such as the Kyiv chant, which in their turn, were replaced by music that was closer to recitative. Most Znamenny melodies gradually become lost or forgotten.[7]

The most notable name in Russian music during the early part of the 19th century—a period which marked a low ebb in the fortunes of traditional Russian music—was Dmitry Bortniansky, who studied in Venice before eventually becoming the director of music at the court chapel in St Petersburg. Composing in an era when attempts were being made to suppress the Russian Empire's cultural heritage, Bortniansky's choral concertos, set to Russian texts, were modelled on counterpoint, the concerto grosso and Italian instrumental music. Vedel followed Bortniansky in combining the Italian Baroque style to ancient Russian hymnody,[7] at a time when classical influences were being introduced into Ukrainian choral music, such as four-voice polyphony, the soloist and the choir singing at different alternative times, and the employment of three or four sections in a work.[6]

Sources

The original biographical sources for Vedel are a biography about his pupil the composer Pyotr Turchaninov, and an article about Vedel by the historian Viktor Askochensky, who based his information on verbal accounts by Vedel's contemporaries and a biography written by Vedel's pupil Vasyl Zubovsky. The composer Vasyl Petrushevsky's biography of Vedel, published in 1901, used similar sources.[8]

Documents relating to Vedel were accidentally discovered in 1967 by the Ukrainian nationalist Vasyl Kuk when he was researching the Moscow military archives about NKVD operations against the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Today, advocates of Vedel such as Mykola Hobdych, the director of the Kyiv Chamber Choir, and the musicologist Tetyana Husarchuk, continue to research and popularize his music.[9] The task of studying Vedel is made more difficult for historians and musicologists because of the fragmentary and superficial nature of the sources—information about his methods is lacking, and his works cannot always be accurately dated.[10]

Life

Family

_-_cropped.svg.png.webp)

Artemy Lukyanovich Vedel was born in Kyiv in the Russian Empire, probably on 13 April 1767.[11][note 2] He was the only son of Lukyan Vlasovych Vedelsky and his wife Elena or Olena Hryhorivna Vedelsky.[12][13] The family lived in Podil, the old trading and crafts centre of Kyiv, in the parish of the St Boris and St Gleb's Church. Their house stood on what is now the corner between Bratska Street and Andriivska Street; Artemy lived there throughout his childhood.[12] Almost half of the population of Kyiv lived in Podil.[14] which was one of the three walled settlements that formed the city, along with Old Kyiv and Pechersk.[15][note 3]

The Vedelsky family adhered strictly to the Orthodox faith.[8] Lukyan Vlasovich Vedelsky was a wealthy carver of iconostases, who owned his own workshop. The name Vedel, probably an abbreviated form of Vedelsky, was how the composer signed his letters, and named himself in military documents. His father signed himself "Kyiv citizen Lukyan Vedelsky".[12][note 4]

Early years in Kyiv

Vedel was a boy chorister in the Eparchial (bishop's) choir in Kyiv.[17] He studied at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, where his teachers included the Italian operatic composer Giuseppe Sarti,[18] who spent 18 years as a composer in the Russian Empire.[19] By the end of the 18th century, most of the students attending the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy were preparing for the priesthood. It was at that time the oldest and most influential higher education institution in the Russian Empire; most of the country’s leading academics were originally graduates of the academy.[20]

Vedel attended the academy until 1787. After that he studied philosophy and music, and began composing as a student of Potemkin's Musical Academy. Whilst studying the advanced philosophy course, he was appointed as the conductor of the academy’s choir—the academy provided extensive programmes for the training of choral singers[21]—and conducted the student orchestra. He also performed as a solo violinist.[12][19] He studied the academy's theoretical books on music, and became acquainted with the religious works (including cantatas) composed by the academy's students, as well as the spiritual concerts of Andriy Rachynsky, and perhaps also those of Sarti and Maxim Berezovsky.[17]

Moscow

In 1788 Vedel, along with other choristers, was sent by Samuel Myslavsky, the Metropolitan of Kyiv and Halych, and the rector of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, to Moscow.[12] There he served as the assistant choir master and a violinist for Pyotr Dmitrievich Yeropkin, the Governor-General of Moscow[18] and, after 1790, by his successor, Alexander Prozorovsky. The choir was at time an artistically important part of the Russian Imperial Court.[12]

Vedel's talent was recognized by other musicians in Moscow. He probably continued his musical studies at the university.[19] During this period, he had the opportunity to become more familiar with the musical cultures of Russia and Western Europe.[12] However, he did not stay in Moscow for a long time, and resigning his position, he returned home to Kyiv.[19]

Patronage under Andrei Levanidov

In Kyiv, Vedel returned to leading the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy choir. Among the famous choirs in the city at that time was one belonging to General Andrei Levanidov at the Kyiv headquarters of the Ukrainian infantry regiment. From early 1794, Levanidov acquired Vedel's services to lead the regimental chapel and the children's choir. Levanidov, who valued and respected Vedel as a composer and a musician, was able to act as an influential patron—the years from 1794 to 1798 saw the zenith of Vedel's musical creativity.[12][19] From 1793 to 1794 he directed the choirs of both the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and his patron.[22] He was rapidly promoted within the army; on 1 March 1794 he was appointed as a staff clerk, and on 27 April 1795 he became a junior adjutant.[12]

In March 1796, Levanidov was appointed as the Governor-General of the Kharkov Governorate. The composer moved to Kharkiv, along with his best musicians. In Kharkov (now Kharkiv, Ukraine) Vedel organized a new gubernia (governorate) choir and orchestra, and taught singing and music at the Kharkiv Collegium,[11] which was second only to the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in terms of its curriculum.[21] The music class at the Kharkiv Collegium was first recorded in 1798, when in January that year two canons and a choral concerto by Vedel were performed.[23]

Vedel did much of his composing during this period.[11] Works included the concerts "Resurrect God" and "Hear the Lord my voice" (dated October 6, 1796) and the two-choir concerto "The Lord Passes Me". The composer and his works were highly valued in Kharkiv; his concerts were studied and performed at the Kharkiv Collegium, and they were sung in churches. Bortniansky, who conducted the St. Petersburg State Academic Capella, praised the quality of Vedel's teaching. In September 1796, Vedel was promoted to become a senior adjutant, with the rank of captain.[12][22]

Decline in fortunes

At the beginning In 1797, on the orders of Tsar Paul I, the Kharkov Governorate was abolished (and replaced by the newly-recreated Sloboda Ukrainian Governorate), and Levanidov left Kharkov. After Paul I decreed that all regimental chapels were to be abolished, Vedel resigned from the army in October 1797. He worked as a musician for the governor of the new province, Aleksey Teplov. Teplov, who as a young man had received an excellent musical education, treated Vedel as well as he could.[12]

The tsar's decrees caused the cultural and artistic life of Kharkiv to decline. The city's theatre was closed, and its choirs and orchestras were dissolved. Performances of Vedel's works in churches were now banned,[12] as the tsar prohibited singing in churches of any form of music except during the Divine Liturgy. After 1798, with Levanidov was removed from his post, Vedel was left without a patron. The loss of Levanidov, which coincided with the decree by the tsar of 10 May 1797 concerning the performance of music in churches, caused Vedel to become deeply depressed.[24]

Despite the support he received from Teplov, Vedel distributed his belongings (including all his manuscripts),[17] left Kharkiv at the end of the summer of 1798, and returned to live at his parents' house in Kyiv. There he wrote two choral concertos, "God, the law-breaker of the rebellion against me" (November 11, 1798) and "To the Lord we always mourn". The concertos were performed in the Epiphany Cathedral and St Sophia Cathedral in the city.[12]

Life as a novice

Early in 1799, frustrated by the lack of opportunities to compose and teach and possibly suffering from a form of mental illness at the time, Vedel enrolled as a novice monk at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra.[12][24] He was an active member of the community and was respected by the monks for his asceticism.[24]

According to Turcaninov’s biography, the Metropolitan of Kyiv commissioned Vedel to write a canticle in honour of a royal visit to Kyiv, but Vedel instead wrote a letter to the tsar, probably of a political nature. Vedel was arrested in Okhtyrka, pronounced insane, and returned to Kyiv.[24]

A few months later, not having found peace of mind, Vedel left the monastery and returned home, where, according to the memoirs of his father, he read, played the violin, and composed new works. He may have returned to teach at the Kyiv Academy.[25] By leaving the monastery before his training was completed, Vedel may have angered Hierotheus, the Metropolitan bishop; when the monastery authorities discovered a book containing handwritten insults about the royal family, the Metropolitan accused Vedel of writing in the book. He dismissed Vedel's servants, and personally detained him. On May 25, 1799, Hierotheus declared that Vedel was mentally ill.[12]

Imprisonment and death

According to Kuk, the official documents relating to Vedel's case show that he was never formally arrested or charged, and that he was never questioned by the authorities or given the opportunity to defend himself. Vedel's case was referred in turn from the governor of Kyiv to the governor of Ukraine Alexander Bekleshov, the Attorney General of Russia, and to the tsar. While the case was being dealt with in St. Petersburg, Vedel, then seriously ill, was placed under his father's care in Kyiv.[12][17] He was found guilty, and was incarcerated at the asylum of St. Cyril's Monastery, Kyiv for an indefinite period.[22] In the asylum, he was forbidden to write or compose.[24] When the asylum was closed in 1803, the patients were moved to a new hospital in Kyiv.[26]

After the death of Paul I in 1801, the new tsar, Alexander I, proclaimed an amnesty for unjustly imprisoned convicts, and many prisoners were released.[25] Alexander ordered that Vedel's case should be re-examined, but Vedel was again declared insane and remained an inmate.[13] The tsar wrote of Vedel on May 15, 1802: "… leave in the present captivity".[17]

After 9 years' imprisonment, and by now mortally ill, Vedel was allowed to return home to his father's house in Kyiv. Shortly before his death there on 14 July 1808, he is said to have stood and prayed in the garden.[13]

There was uncertainty about the exact date of Vedel's death, until his death certificate was found in 1910.[27] The cause of Vedel's death was never revealed by the authorities.[17] His friend Ioann Levanda, the archpriest of Kyiv Cathedral and a well-known preacher, obtained permission for a proper funeral, even though Vedel had been incarcerated in an asylum. A large number of mourners attended Vedel's funeral, including students from the Academy.[13][17] He was buried in the Shchekavytsia cemetery. When the area was redeveloped In the 1930s, the cemetery was destroyed.[13][22] The location of Vedel's grave is now lost.[12]

Appearance and character

No portrait of Vedel has survived, but he was described by friends as being gentle, calm, friendly, and with “beautiful radiant eyes, burning with a special fire of great spiritual nobility and inspiration”.[17] His letters to Turchaninov reveal a care for oppressed people—reflected in his choice of themes for his concertos—and his opposition towards serfdom, which had been established in the Ukraine by Catherine the Great.[27]

Music

Compositions

.jpg.webp)

Vedel was almost entirely a liturgical composer of the a cappella choral music sung in Orthodox churches.[11][note 5] As of 2011, more than 80 of his compositions have been identified, including 31 choral concertos and six trios, two liturgies, an All-night vigil,[11][12] and three irmos cycles.[28] An edition of Vedel's works was published by Mykola Hodbych and Tetiana Husarchuk in 2007.[11]

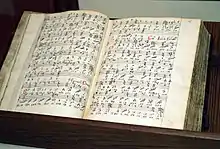

Many of Vedel's works have been lost.[17] The V.I. Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine holds the only existing autograph score by the composer, the "Score of Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom and Other Compositions". The score consists of 12 choral concertos (composed between 1794 and 1798),[17] and the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom. The ink varies in colour, which suggests that Vedel worked on the compositions at different times.[29] It was acquired by Askochensky, who bequeathed it to the Kyiv Academy.[17][30]

Musical style

Musicologists consider him to the archetypal composer of Ukrainian music from the Baroque era. An outstanding tenor singer, Vedel was one of the best choral conductors of his time. He helped to raise the standard of Ukrainian choral singing to previously unknown levels.[6]

Vedel was considered to be traditional and conservative composer, unlike than his older contemporaries Berezovsky and Dmitry Bortniansky. Unlike Vedel, they composed secular, non-spiritual works; although he was a famous violinist, no music by Vedel for the violin is documented. His works, perhaps even more than those of Berezovsky or Bortnyansky, represented a development in Ukrainian musical culture.[9] According to Koshetz, Vedel's music was based on Ukrainian folk melodies.[28]

Vedel’s music was written at a time when Western music was emerging from the Renaissance and Baroque eras. The style of his compositions, which reflect the changes taking place in Western music during this period, was influenced by the baroque traditions of the Ukrainian hetman culture (see: Ukrainian Baroque), but was also influenced by West European operatic and instrumental styles of the time.[31]

Legacy

Censorship and revival

Performances of Vedel's music were censored and the publication of his scores was prohibited during most of the 19th century. Distributed in secret in manuscript form, they were known and performed, despite the ban.[12] Hand-written variations of Vedel's music appeared,[10] as conductors amended the scores to make them more suitable for unauthorized performances. Tempi were changed and modal textures, the level of complexity of the music, and the formal structure were all altered.[32] The hand copying of Vedel's music led to the creation of versions that were notably different from his original scores.[25]

Vedel's compositions were rediscovered during the early 20th century by the conductor and composer Alexander Koshetz, at that time the leader of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy's student choir, and himself a student.[17] They were first published in 1902.[33] Koshetz, one of the earliest Ukrainian conductors to attempt to revive performances of Vedel using the autograph scores, noted that “the great technical difficulties of solo parts... and the need for large choruses" made his works difficult to perform in public.[32] Koshetz toured Europe and America, conducting the Ukrainian Republican Chapel in performances of Vedel.[9]

Koshetz's revival of Vedel's music was banned by the Soviets after Ukraine was absorbed into the Soviet Union.[17] Unlike much of the sacred works written by Western composers, Orthodox sacred music is sung in the vernacular, and its religious nature is visible and tangible to Orthodox Christians. Because of this, Soviet anti-religious legislation prohibited Russian and Ukrainian sacred music from being performed in public from 1928 until well into the 1950s, when Khrushchev Thaw occurred, and Vedel's works were once again heard by Soviet audiences.[34]

The gap of nearly two centuries when Vedel's music was forgotten adversely affected the development of church music in Ukraine. The lack of manuscripts and primary sources about Vedel led to a lack of awareness of his significance in the development of music in the late 18th century.[28] Early attempts to produce a narrative of Vedel’s life and work based on the recollections of his contemporaries were only begun after they themselves had died, and this led to contradictory accounts of his life. The most important studies about Vedel produced in 19th and early 20th century belonged to musicologists as Askochensky, Vasily Metalov, Vladimir Stasov, and Pyotr Turchaninov. Some of these authors such as Askochensky belonged to representatives of the Russian national movement, howether, according to Igor Tylyk and Oksana Dondyk the historical studies of these authors were distorted to suit their particular views about the politics and music of Ukraine.[10]

Recognition

Vedel, Berezovsky and Bortniansky are recognized by modern scholars as the 'Golden Three' composers of Ukrainian classical music during the end of the 18th century,[35] and the outstanding composers at a time when church music was reaching its peak in eastern Europe.[8] They composed some of Russia's greatest choral music.[21]

Vedel made an important contribution in the music history of Ukraine,[36][37] and musicologists consider him to the archetypal composer of the baroque style in Ukrainian music.[11] Koshetz stated that Vedel should be seen as "the first and greatest spokesperson of the national substance in Ukrainian church music".[28] According to the ethnomusicologist Taras Filenko, Vedel's works were part of the foundation on which the Ukrainian liturgical and secular musical culture of the 19th century continued to develop, and his ability to compose choral works, combined with innovations in adapting the particularities of Ukrainian melody, make his works a unique phenomenon in the context of world musical culture.[38] According to Chekan, Vedel’s texture is "at times monumental and at others subtly contrasted, strikingly showing the possibilities of the a cappella sound".[6]

A memorial plaque to Vedel was made by the sculptor Igor Grechanyk in 2008. The plaque is located on the wall of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.[39] The Vedel School in Lviv, a school of contemporary music founded in 2017 by the musician Mikhail Balog, was named in honour of the composer.[40] There are streets named after the composer in Kyiv and Kharkiv.[26][41]

In 2016 the Ukrainian government announced its intention to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Vedel's birth in 2017.[42]

Notes

- Monodies were written in a particular way using symbols called znameny ("banner" symbols) to represent how the music was sung.[6]

- The date of Vedel's birth is not known for certain. Using the Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendar, a child's baptism name was given in honour of the saint whose day falls closest to the date of birth of the child. The martyrs Artemon and Artemison were commemorated on 13 April and 29 April (Old Style).[12]

- Most of Podil was destroyed by a fire in 1811, after which the area was redeveloped and a new street layout was built.[16]

- The name Vedel is not itself of Slavic origin, but is common in western Europe, especially in northern Germany, Denmark and Norway.[8]

- In Orthodox Christianity, musical instruments are not used, and singing is an essential ingredient in church services.[21]

References

- Bertil van Boer: Historical Dictionary of Music. Scarecrow, 2012. P. 577.

- Dowley, Tim: Christian Music: A global history. Fortress Press 2018

- Goncharuk A. Y. Socio-pedagogical foundations of the theory and history of musical art (Гончарук А. Ю. Социально-педагогические основы теории и истории музыкального искусства). Moscow 2015. P. 196.

- Razumovsky D. V. Church singing in Russia (Разумовский Д. В. Церковное пение в России). Moscow 2013. P. 13.

- Askochensky V. Russian composer Artemy Vedelev (Аскоченскій В. Русский композиторъ А. Л. Веделевъ. — Газета «Кіевские губернские вѣдомости»). Kiev 1854, № 10.

- Chekan, Yurii (15 October 2012). "A Millennial Tradition: the Choral Art of Ukraine". International Choral Bulletin. Translated by Kohut, Myroslaw. International Federation for Choral Music. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- Quantrill, Peter (2021). "Russian Orthodox Choral Music" (Compact disc notes). Brilliant Classics.

- Sonevytsky 1966, p. 161.

- "Television "through the eyes of culture" – No 28 Non-world Artem Knowledge". Lviv Polytechnic National University. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- Tylyk & Dondyk 2018, pp. 58–59.

- Sonevytsky, Ihor; Stech, Marko Robert. "Vedel, Artem". Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Ведель Артем Лук'янович – композитор, диригент, співак, скрипаль" [Artem Lukyanovich in charge: composer, conductor, singer, violinist]. History of the Academy (in Ukrainian). National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Grinevich, Victor (10 July 2008). "Артемій Ведель помер, молячись у батьківському саду" [Artemiy Vedel died praying in his parents' garden]. Gazetta (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- Hamm 1993, p. 10.

- Hamm 1993, pp. 19–21.

- Hamm 1993, p. 19.

- Yatsenko, Andriy. "Artemy Lukyanovich Vedel". Ukrainian Radio Station of Classical Music. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- van Boer 2012, p. 577.

- Sonevytsky 1966, p. 162.

- Magocsi 2010, p. 301.

- Magocsi 2010, p. 302.

- Katchanovski et al. 2013, p. 734.

- Korniy 1998, p. 675.

- Sonevytsky 1966, p. 163.

- Filenko 2018, p. 5.

- Rudyachenko, Alexander (9 August 2019). "Боголюбий меланхолік: Згадуємо Артемія Веделя — одного з фундаторів української національної музики" [God-loving melancholic: We remember Artemy Wedel – one of the founders of Ukrainian national music]. The Day (Kyiv) (in Ukrainian, Russian, and English). Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- Sonevytsky 1966, p. 164.

- Filenko 2018, p. 3.

- "Score of Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom and Other Compositions by Artemiĭ Vedelʹ". Library of Congress. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Sonevytsky 1966, p. 165.

- Tylyk 2016, pp. 193–194.

- Filenko 2018, p. 6.

- Sonevytsky 1966, pp. 164–165.

- Fairclough 2012, p. 69.

- "Artem Vedel: Twelve Sacred Choral Concerti & Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom". Leaf Music Inc. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- van Boer 2012, p. 619.

- Ritzarev 2016, p. 298.

- Filenko 2018, p. 10.

- "Artemiy Vedel". Igor Grechanyk. 28 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- "Музыкант Михаил Балог о школе современной музыки Vedel School" [Musician Mikhail Balog and the Vedel School, a school of contemporary music]. Vogue Ukraine (in Russian). 6 September 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Artema Vedelia St, Kharkiv, Kharkivs'ka oblast, Ukraine, 61000". Google Maps. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- "On the celebration of memorable dates and anniversaries in 2017". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

Sources

- van Boer, Bertil (2012). Historical Dictionary of Music. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81087-183-0.

- Fairclough, Pauline (2012). ""Don't Sing It on a Feast Day": The Reception and Performance of Western Sacred Music in Soviet Russia, 1917–1953". Journal of the American Musicological Society. University of California Press. 65 (1): 67–111. doi:10.1525/jams.2012.65.1.67. JSTOR 10.1525/jams.2012.65.1.67.

- Filenko, Taras (2018). Artem Vedel: Twelve Sacred Choral Concerti & Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (PDF) (in English and Ukrainian). Halifax, Canada: Leaf Music Inc.

- Hamm, Michael F. (1993). Kiev: a portrait, 1800–1917. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-14008-5-151-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Katchanovski, Ivan; Kohut, Zenon E.; Nebesio, Bohdan Y.; Yurkevich, Myroslav (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ukraine (2nd ed.). Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-08108-7-847-1.

- Korniy, Lydia Pylypyvna (1998). Історія української музики [History of Ukrainian Music] (in Ukrainian). Vol. 2. Kharkiv; New York: P. Kotz. OCLC 978701286.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-14426-1-021-7.

- Ritzarev, Marina (2016). Eighteenth-century Russian Music. Abingdon, UK; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-3466-9.

- Sonevytsky, Igor (1966). Artem Vedelʹ i ĭoho muzychna spadshchyna [Artem Vedel and his Musical Heritage] (in Ukrainian). New York: Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States. OCLC 12901903.

- Tylyk, Igor (2016). "Khronotopichno-stylovi parametry tvorchosti Artemiia Vedelia" [Chronotopic and stylistic parameters of Artemy Vedel's work]. Scientific Herald of Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine (in Ukrainian) (117): 181–194.

- Tylyk, Igor; Dondyk, Oksana (2018). "Формування науково-аналітичних параметрів вивчення творчості Артема Веделя крізь призму музикознавчо-текстологічних досліджень другої половини ХІХ – середини ХХ століття" [Formation of scientific and analytical parameters of studying the work of Artem Wedel through the prism of musicological and textological research of the second half of the XIX – middle of the XX century]. Scientific Notes (in Ukrainian and English). Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University. 2 (39): 57–66. ISSN 2411-3271.

Further reading

- In English

- Kostyuk, Nataliya (2016). "The Kiev Theological Academy Choir: Organization, Tradition and Experimentation". Journal of the International Society for Orthodox Church Music. 2: 44–50. ISSN 2342-1258.

- Kovalchuk, Natalia; Zosim, Olga; Ovsiankina, Liudmyla; Lomachinska, Irina; Rykhlitska, Oksana (2022). "Features of Sacred Music in the Context of the Ukrainian Baroque". Religions. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 13 (88): 88. doi:10.3390/rel13020088.

- Tylyk, Ihor (2019). "Specificity of the Figurative-dramaturgic Interaction of the Musical and Verbal-text Concepts in the Works of Artemy Vedel". Bulletin of Kyiv National University of Culture and Arts. Series in Musical Art. 2 (2): 140–150. doi:10.31866/2616-7581.2.2.2019.187439. S2CID 213899222.

- In Ukrainian or Russian

- Askochensky, Victor Ipatievich (1863). Protoiyerey Petr Ivanovich Turchaninov [Archpriest Peter Ivanovich Turchaninov] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Edward Weimar.

- Husarčuk, Tetjana Volodymyrivna (2019). Артемій Ведель: постать митця у контексті епох [Artemiy Vedel: the artist in the context of his age] (in Ukrainian). Kyïv: Muzyčna Ukraïna. ISBN 978-966-8259-87-6.

- Karas, Ganna (2018). "Постать Артемія Веделя В Культурно-Мистецьких Рефлексіях Української Діаспори" [Artemy Vedel and the Culture and Art of the Ukrainian Diaspora]. Scientific Herald of the Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine (in Ukrainian) (121). doi:10.31318/2522-4190.2018.121.133109.

- Semion, Viktoriia.V. (2019). "Народнопісенні Витоки Хорової Поліфонії Артемія Веделя" [The Folk Song Roots of Artemy Vedel’s Choir Polyphony] (PDF). Young Scientist. Kharkiv National Kotlyarevsky University of Arts. 69 (5): 101–105. doi:10.32839/2304-5809/2019-5-69-21. S2CID 198037196.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Artemy Vedel. |

- Free scores by Artemy Vedel at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- "Artemi Vedel". Discogs. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Information about Vedel's compositions from the online Orthodox Sacred Music Reference Library

- Free sheet music of works by Vedel at iKliros (in Russian)