Apocalypse of Peter

The Apocalypse of Peter (or Revelation of Peter) is an early Christian text of the 2nd century and an example of apocalyptic literature with Hellenistic overtones. It is not included in the standard canon of the New Testament, but is mentioned in the Muratorian fragment, the oldest surviving list of New Testament books, which also states some among authorities would not have it read in church. The text is extant in two incomplete versions of a lost Greek original, a later Greek version and an Ethiopic version, which diverge considerably.

The Apocalypse of Peter is purportedly written by the disciple Peter and describes a divine vision by Christ. After inquiring for signs of the Second Coming of Jesus (parousia), the work details both heavenly bliss for the saved and infernal punishments for the damned. In particular, the punishments are graphically described in a physical sense, and generally correspond to lex talonis ("an eye for an eye"): blasphemers are hung by their tongues, liars who bear false witness have their tongues set on fire eternally; callous rich people are made to wear rags and be pierced by sharp stones as would beggars; and so on. It is a very early example of the same genre of the more famous Divine Comedy of Dante.

Manuscript history

Before 1886, the Apocalypse of Peter had been known only through quotations and references in early Christian writings. In addition, some common lost source had been necessary to account for closely parallel passages in such apocalyptic Christian literature as the Apocalypse of Esdras, the Apocalypse of Paul, and the Passion of Saint Perpetua, although identification of this lost source with the Apocalypse of Peter was not known.

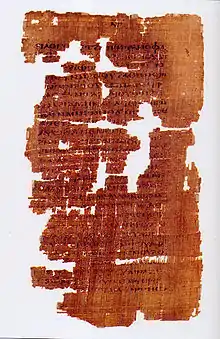

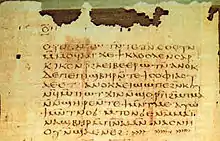

A fragmented Koine Greek manuscript was discovered during excavations initiated by Gaston Maspéro during the 1886–87 season in a desert necropolis at Akhmim in Upper Egypt. The fragment consisted of parchment leaves of the Greek version that was claimed to be deposited in the grave of a Christian monk of the 8th or 9th century.[1] The manuscript is in the Coptic Museum in Old Cairo. A republication of Ethiopic documents from 1907–1910 discovered a strong correspondence with the Akhmim Apocalypse of Peter, causing M. R. James and other scholars to realize that these were Ethiopic versions of the same work; further Ethiopic copies have been discovered since.[2] These Ethiopic versions appear to have been translated from Arabic, which itself was translated from the lost Greek original. Two other short Greek fragments of the work have been discovered: a 5th-century fragment at the Bodleian that had been discovered in Egypt in 1895, and the Rainer fragment which perhaps comes from the 3rd or 4th century.[3][4] These fragments offer significant variations from the other versions.

As compiled by William MacComber and others, the number of Ethiopic manuscripts of this same work continue to grow. The Ethiopic work is of colossal size and post-conciliar provenance, and therefore in any of its variations it has minimal intertextuality with the Apocalypse of Peter which is known in Greek texts.

In general, most scholars believe that the Ethiopic versions we have today are closer to the original manuscript, while the Greek manuscript discovered at Akhmim is a later and edited version.[3] This is for a number of reasons: the Akhmim version is shorter, while the Ethiopic matches the claimed line count from the Stichometry of Nicephorus; patristic references and quotes seem to match the Ethiopic version better; and the Akhmim version seems to be attempting to integrate the Apocalypse with the Gospel of Peter (also in the Akhmim manuscript), which would naturally result in revisions.[5]

Dating

The Apocalypse of Peter seems to have been written between 100 AD and 150 AD. The terminus post quem—the point after which we know the Apocalypse of Peter must have been written—is shown by its use (in Chapter 3) of 4 Esdras, which was written about 100 AD.[3] If the Apocalypse was used by Clement or the author of the Sibylline Oracles, then it must have been in existence by 150 AD.[5]

The Muratorian fragment, the earliest existing list of canonical sacred writings of the New Testament, which is assigned on internal evidence to the last quarter of the 2nd century (c. 175–200), gives a list of works read in the Christian churches that is similar to the modern accepted canon; however, it also includes the Apocalypse of Peter. The Muratorian fragment states: "the Apocalypses also of John and Peter only do we receive, which some among us would not have read in church." (The existence of other Apocalypses is implied, for several early apocryphal ones are known: see Apocalyptic literature.) The scholar Oscar Skarsaune makes a case for dating the composition to the Bar Kochba revolt (132–136).[6]

Content

The Apocalypse of Peter is framed as a discourse of the Risen Christ to his faithful, offering a vision first of heaven, and then of hell, granted to Peter. Theorized as written in the form of a nekyia,[7] it goes into elaborate detail about the punishment in hell for each type of crime and the pleasures given in heaven for each virtue.

In heaven, in the vision,

- People have pure milky white skin, curly hair, and are generally beautiful

- The earth blooms with everlasting flowers and spices

- People wear shiny clothes made of light, like the angels

- Everyone sings in choral prayer

The punishments in the vision each closely correspond to the past sinful actions in a version of the Jewish notion of an eye for an eye, that the punishment may fit the crime.[8] Some of the punishments in hell according to the vision include:

- Blasphemers are hanged by the tongue.

- Women who "adorn" themselves for the purpose of adultery, are hung by the hair over a bubbling mire. The men who had adulterous relationships with them are hung by their feet, with their heads in the mire, next to them.

- Murderers and those who give consent to murder are set in a pit of creeping things that torment them.

- Men who take on the role of women in a sexual way, and lesbians, are "driven" up a great cliff by punishing angels, and are "cast off" to the bottom. Then they are forced up it, over and over again, ceaselessly, to their doom.

- Women who have abortions are set in a lake formed from the blood and gore from all the other punishments, up to their necks. They are also tormented by the spirits of their unborn children, who shoot a "flash of fire" into their eyes. (Those unborn children are "delivered to a care-taking" angel by whom they are educated, and "made to grow up.")

- Those who lend money and demand "usury upon usury" stand up to their knees in a lake of foul matter and blood.

"The Revelation of Peter shows remarkable kinship in ideas with the Second Epistle of Peter. It also presents notable parallels to the Sibylline Oracles[9] while its influence has been conjectured, almost with certainty, in the Acts of Perpetua and the visions narrated in the Acts of Thomas and the History of Barlaam and Josaphat. It certainly was one of the sources from which the writer of the Vision of Paul drew. And directly or indirectly it may be regarded as the parent of all the mediaeval visions of the other world."[10]

The Gospel parables of the budding fig tree and the barren fig tree, partly selected from the parousia of Matthew 24,[11] appear only in the Ethiopic version (ch. 2). The two parables are joined, and the setting "in the summer" has been transferred to "the end of the world", in a detailed allegory in which the tree becomes Israel and the flourishing shoots become Jews who have adopted Jesus as Messiah and achieve martyrdom. It is possible this was edited out of the Greek version due to incipient anti-Jewish tensions in the church; a depiction of Jews converting and Israel being especially blessed may not have fit the mood in later centuries of the Church as some Christians strongly repudiated Jews.[12]

In the version of the text in the 3rd century Rainer Fragment, the earliest fragment of the text, Chapter 14 describes the salvation of those condemned sinners for whom the righteous pray. The sinners are saved out of Hell through their baptism in the Acherusian Lake.[13]

In the Ethiopic sources, there is a section following the main body of The Apocalypse of Peter that scholars like R.B. Bauckham consider to be a separate story written centuries later based on Chapter 14.[14] This separate story explains that in the end God will save all sinners from their plight in Hell:

- "My Father will give unto them all the life, the glory, and the kingdom that passeth not away, ... It is because of them that have believed in me that I am come. It is also because of them that have believed in me, that, at their word, I shall have pity on men... "

Thus, in this additional story, sinners will finally be saved by the prayers of those in heaven. Peter then orders his son Clement not to speak of this revelation since God had told Peter to keep it secret:

- [and God said]"... thou must not tell that which thou hearest unto the sinners lest they transgress the more, and sin".

Genre

The Apocalypse of Peter differs from the Apocalypse of John in putting far more stress on the afterlife and divine rewards and punishments than Revelation's focus on a cosmic battle between good and evil. Still, it and other works such as the Apocalypse of Thomas provide an early example of a genre of explicit depictions of heaven and hell. Most famously, Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy would become extremely popular and celebrated in later centuries.[3]

The Apocalypse of Peter, with its Hellenistic Greek overtones, belongs to the same genre as the Clementine literature that was popular in Alexandria. Like the Clementine literature, the Apocalypse of Peter was written for an intellectually simple, popular audience and had a wide readership.

Debate over canonicity

As discussed in dating the Apocalypse of Peter, the Muratorian fragment mentions the Apocalypse, but also states that "some among us would not have read in church." Both the Apocalypse of Peter and Apocalypse of John appear to have been controversial, with some churches of the 2nd and 3rd centuries using them and others not. Clement of Alexandria appears to have considered the Apocalypse of Peter to be holy scripture. Eusebius personally found the work dubious, but his book Church History describes a lost work of Clement's, the Hypotyposes (Outlines), that gave "abbreviated discussions of the whole of the registered divine writings, without passing over the disputed [writings] — I mean Jude and the rest of the general letters, and the Letter of Barnabas, and the so-called Apocalypse of Peter."[15][16] The Stichometry of Nicephorus also lists it as a used if disputed book.[12] Although the numerous references to it attest that it was in wide circulation in the 2nd century, the Apocalypse of Peter was ultimately not accepted into the Christian canon.[17] The reason why is not entirely clear, although considering the reservations various church authors had on the Apocalypse of John (that is, the Book of Revelation), likely similar considerations were in play. As late as the 5th century, Sozomen indicates that some churches in Palestine used it in his time, but by then, it seems to have been considered inauthentic by most Christians.

One hypothesis for why the Apocalypse of Peter failed to gain enough support to be canonized, propounded by Bart Ehrman, is that its view on the afterlife was too aberrant for the views of theologians of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries. A passage of the Apocalypse of Peter found in only one source (the Rainer fragment, which does not include the whole text) writes that dead saints, seeing the torment of sinners and heretics from heaven, could ask God for mercy, and these damned souls could be retroactively baptized and saved. Many Church theologians of the era strongly felt that salvation and damnation were eternal and strictly based on actions and beliefs while alive. However, such a system, where saints could pray their friends and family out of hell, was possibly too arbitrary for their tastes. How often this variant was used is unknown, but the lack of this passage in many versions suggests that the passage itself was not always copied, perhaps by scribes who felt it in error.[18] M. R. James went even further, suggesting that the original Apocalypse of Peter may well have suggested universal salvation after a period of suffering in hell, and that was the reason it was received unfavorably by some.[5]

The Ru'ya Butrus

There are more than 100 manuscripts of an Arabic Christian work entitled the Ru'ya Butrus, which is Arabic for the 'Vision' or 'Apocalypse' of Peter.[19] Additionally, as catalogues of Ethiopic manuscripts continue to be compiled by William MacComber and others, the number of Ethiopic manuscripts of this same work continue to grow. It is critical to note that this work is of colossal size and post-conciliar provenance, and therefore in any of its recensions it has minimal intertextuality with the Apocalypse of Peter, which is known in Greek texts. Further complicating matters, many of the manuscripts for either work are styled as a "Testament of Our Lord" or "Testament of Our Savior". Further, the southern-tradition, or Ethiopic, manuscripts style themselves "Books of the Rolls", in eight supposed manuscript-rolls.

In the first half of the 20th century, Sylvain Grebaut published a French translation, without Ethiopic text, of this monumental work.[20] A little later, Alfons Mingana published a photomechanical version and English translation of one of the monumental manuscripts in the series Woodbrooke Studies. At the time, he lamented that he was unable to collate his manuscript with the translation published by Grebaut. That collation, together with collation to some manuscripts of the same name from the Vatican Library, later surfaced in a paper delivered at a conference in the 1990s of the Association pour l'Etudes des Apocryphes Chretiennes. There seem to be two different "mega-recensions", and the most likely explanation is that one recension is associated with the Syriac-speaking traditions, and that the other is associated with the Coptic and Ethiopic/Ge'ez traditions. The "northern" or Syriac-speaking communities frequently produced the manuscripts entirely or partly in karshuni, which is Arabic written in a modified Syriac script.

Each "mega-recension" contains a major post-conciliar apocalypse that refers to the later Roman and Byzantine emperors, and each contains a major apocalypse that refers to the Arab caliphs. Of even further interest is that some manuscripts, such as the Vatican Arabo manuscript used in the aforementioned collation, contains no less than three presentations of the same minor apocalypse, about the size of the existing Apocalypse of John, having a great deal of thematic overlap, yet quite distinct textually.

Textual overlaps exist between the material common to certain Messianic-apocalyptic material in the Mingana and Grebaut manuscripts, and material published by Ismail Poonawala.[21] The manuscripts having the "Book of the Rolls" structure generally contain a recension of the well-known "Treasure Grotto" text. The plenary manuscripts also generally contain an "Acts of Clement" work that roughly corresponds to the narrative or "epitome" story of Clement of Rome, known to specialists in pseudo-Clementine literature. Finally, some of the plenary manuscripts also contain "apostolic church order" literature; a collation of that has also been presented at a conference of the Association pour l'Etudes des Apocryphes Chretiennes.

Collations of these manuscripts can be daunting, because a plenary manuscript in Arabic or Ethiopic/Ge'ez is typically about 400 pages long, and in a translation into any modern European language, such a manuscript will come to about 800 pages.

Overall, it may be said of either recension that the text has grown over time, and tended to accrete smaller works. There is every possibility that the older portions that are in common to all of the major manuscripts will turn out to have recensions in other languages, such as Syriac, Coptic, Classical Armenian, or Old Church Slavonic. Work on this unusual body of medieval Near Eastern Christianity is still very much in its infancy.

Notes

- Jan N. Bremmer; István Czachesz (2003). The Apocalypse of Peter. Peeters Publishers. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-90-429-1375-2.

- The Ethiopic text, with a French translation, was published by S. Grébaut, Littérature éthiopienne pseudo-Clémentine", Revue de l'Orient Chrétien, new series, 15 (1910), 198–214, 307–23.

- Maurer, Christian (1965) [1964]. Schneemelcher, Wilhelm (ed.). New Testament Apocrypha: Volume Two: Writings Relating to the Apostles; Apocalypses and Related Subjects. Translated by Wilson, Robert McLachlan. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. p. 663–668. Translation from Ethiopian to German by H. Duensing.

- The Greek Akhmim text was printed by A. Lods, "L'evangile et l'apocalypse de Pierre", Mémoires publiés par les membres de la mission archéologique au Caire, 9, M.U. Bouriant, ed. (1892:2142-46); the Greek fragments were published by M.R. James, "A new text of the Apocalypse of Peter II", JTS 12 (1910/11:367-68).

- Elliott, James Keith (1993). The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford University Press. p. 593–595. ISBN 0-19-826182-9.

- Oscar Skarsaune (2012). Jewish Believers in Jesus. Hendrickson Publishers. pp. 386–388. ISBN 978-1-56563-763-4. Skarsaune argues for a composition by a Jewish-Christian author in Israel during the Bar Kochba revolt. The text speaks of a single false messiah who has not yet been exposed as false. The reference to the false messiah as a "liar" may be a Hebrew pun turning Bar Kochba's original name, Bar Kosiba, into Bar Koziba, "son of the lie".

- The Apocalypse of Peter was presented as a nekyia, or journey through the abode of the dead, by A. Dieterich, Nekyia (1893, reprinted Stuttgart, 1969); Dieterich, who had only the Akhmim Greek text, postulated a general Orphic cultural context in the attention focused on the house of the dead.

- Pointed out in detail by David Fiensy, "Lex Talionis in the 'Apocalypse of Peter'", The Harvard Theological Review 76.2 (April 1983:255–258), who remarks "It is possible that where there is no logical correspondence, the punishment has come from the Orphic tradition and has simply been clumsily attached to a vice by a Jewish redactor." (p. 257).

- Specifically Sibylline Oracles ii., 225ff.

- Roberts-Donaldson introduction.

- The canonic New Testament context of this image is discussed under Figs in the Bible; Richard Bauckham, "The Two Fig Tree Parables in the Apocalypse of Peter", Journal of Biblical Literature 104.2 (June 1985:269–287), shows correspondences with wording of the Matthean text that does not appear in the parallel passages in the synoptic gospels of Mark and Luke.

- Ehrman, Bart (2012). Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics. Oxford University Press. p. 457–465. ISBN 9780199928033.

- R. B. Bauckham, The Fate of the Dead: Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses, BRILL, 1998, p. 145.

- Bauckham, The Fate of the Dead, p. 147. Bauckham writes that in the Ethiopic manuscripts, the Apocalypse of Peter forms the first part of the work called "The Second Coming of Christ and the Resurrection of the Dead." He explains that in the Ethiopic sources, the complete story of the Apocalypse of Peter "is readily distinguishable from the secondary continuation which has been attached to it and which begins: "Peter opened his mouth and said to me, 'Listen, my son Clement.'" [Its] relevance... is that [it refers] to the secret mystery revealed by Christ to Peter, of the divine mercy to sinners secured by Christ's intercession for them at the Last Judgment. In particular this is the central theme of the... work, 'The second coming of Christ and the resurrection of the dead,' and was presumably inspired by the passage about the salvation of the damned in ApPet 14..."

- Eusebius of Caesarea (2019) [c. 320s]. "Book 6, Chapter 14". The History of the Church. Translated by Schott, Jeremy M. Oakland, California: University of California Press. p. 297. ISBN 9780520964969.

- Clement 41.1–2 48.1 correspond with the Ethiopian text M. R. James in introduction to Translation and Introduction to Apocalypse of Peter. The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924)

- Perrin, Norman The New Testament: An Introduction, p. 262

- Ehrman, Bart (January 30, 2019). "The Aberrant View of the Afterlife in the Apocalypse of Peter". The Bart Ehrman Blog: The History & Literature of Early Christianity. Retrieved January 27, 2022.. See also the earlier post Finally. Why Did the Apocalypse of Peter Not Make It Into the Canon?

- These may be found in Georg Grag, Die Arabische Christliche Schriftsteller, in the Vatican series Studi e Testi.

- Grebaut [title]

- Poonawala, "Shi'ite Apocalyptic" in M. Eliade, ed., Encyclopedia of World Religions

Further reading

- Eileen Gardiner, Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante (New York: Italica Press, 1989), pp. 1–12, provides an English translation of the Ethiopic text.

External links

- The Apocalypse of Peter Online translation of the work.

- The Apocalypse of Peter (Greek Text) transcribed by Mark Goodacre from E. Klostermann's edition (HTML, Word, PDF)

- Pardee, Cambry. “Apocalypse of Peter.” e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha

- Development of the Canon of the new testament: Apocalypse of Peter

- M. R. James' 1924 introduction

- Bibliography on the Apocalypse of Peter.