Anomodont

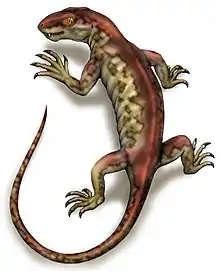

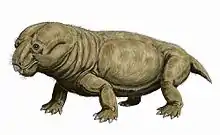

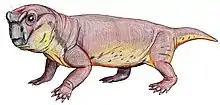

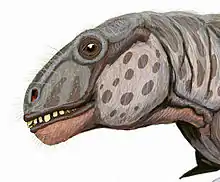

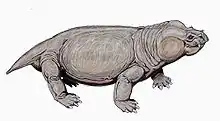

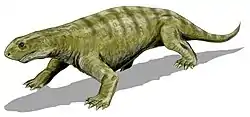

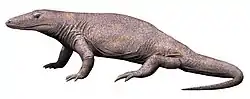

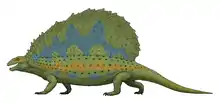

Anomodontia is an extinct group of non-mammalian therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods.[1] By far the most speciose group are the dicynodonts, a clade of beaked, tusked herbivores.[2] Anomodonts were very diverse during the Middle Permian, including primitive forms like Anomocephalus and Patranomodon and groups like Venyukovioidea and Dromasauria. Dicynodonts became the most successful and abundant of all herbivores in the Late Permian, filling ecological niches ranging from large browsers down to small burrowers. Few dicynodont families survived the Permian–Triassic extinction event, but one lineage (Kannemeyeriiformes) evolved into large, stocky forms that became dominant terrestrial herbivores right until the Late Triassic, when changing conditions caused them to decline, finally going extinct during the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event.

| Anomodonts Temporal range: Middle Permian-Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of Lystrosaurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia Owen, 1859 |

| Subgroups | |

Classification

Taxonomy

- Order Therapsida

- Suborder Anomodontia

- Biseridens

- Patranomodon

- clade Anomocephaloidea

- Superfamily Venyukovioidea

- Family Otsheridae

- Family Venyukoviidae

- Clade Chainosauria

- Galechirus

- Galeops

- Galepus

- Infraorder Dicynodontia

Phylogeny

Cladogram modified from Liu et al. (2009):[1]

| Therapsida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Below is a cladogram from Kammerer et al. (2013).[3] The data matrix of Kammerer et al. (2013), a list of characteristics that was used in the analysis, was based on that of Kammerer et al. (2011), which followed a comprehensive taxonomic revision of Dicynodon.[4] Because of this, many of the relationships found by Kammerer et al. (2013) are the same as those found by Kammerer et al. (2011). However, several taxa were added to the analysis, including Tiarajudens Eubrachiosaurus, Shaanbeikannemeyeria, Zambiasaurus and many "outgroup" taxa (positioned outside Anomodontia), while other taxa were re-coded. As in Kammerer et al. (2011), the interrelationships of non-kannemeyeriiform dicynodontoids are weakly supported and thus vary between the analyses.[3]

| 1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Liu, J.; Rubidge, B.; Li, J. (2009). "A new specimen of Biseridens qilianicus indicates its phylogenetic position as the most basal anomodont". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1679): 285–292. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0883. PMC 2842672. PMID 19640887.

- Chinsamy-Turan, A. (2011) Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation - Histology - Biology, p.39. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253356970. Retrieved May 2012

- Kammerer, C. F.; Fröbisch, J. R.; Angielczyk, K. D. (2013). Farke, Andrew A (ed.). "On the Validity and Phylogenetic Position of Eubrachiosaurus browni, a Kannemeyeriiform Dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e64203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064203. PMC 3669350. PMID 23741307.

- Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Fröbisch, J. (2011). "A comprehensive taxonomic revision of Dicynodon (Therapsida, Anomodontia) and its implications for dicynodont phylogeny, biogeography, and biostratigraphy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (Suppl. 1): 1–158. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.627074. S2CID 84987497.

.jpg.webp)