Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

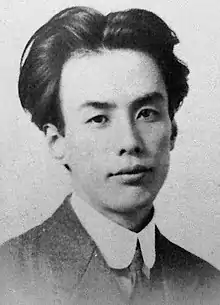

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (芥川 龍之介, Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, 1 March 1892 – 24 July 1927), art name Chōkōdō Shujin (澄江堂主人),[2] was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him.[3] He committed suicide at the age of 35 through an overdose of barbital.[4]

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Native name | 芥川 龍之介 | ||||

| Born | Ryūnosuke Niihara (新原 龍之介) 1 March 1892 Kyōbashi, Tokyo, Empire of Japan | ||||

| Died | 24 July 1927 (aged 35) Tokyo, Empire of Japan | ||||

| Occupation | Writer | ||||

| Language | Japanese | ||||

| Nationality | |||||

| Alma mater | University of Tokyo | ||||

| Genre | Short stories | ||||

| Literary movement | Modernism[1] | ||||

| Notable works | |||||

| Spouse | Fumi Akutagawa | ||||

| Children | 3 (including Yasushi Akutagawa) | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 芥川 龍之介 | ||||

| Hiragana | あくたがわ りゅうのすけ | ||||

| |||||

Early life

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa was born in the Kyōbashi district of Tokyo, the third child and only son of father Toshizō Niihara and mother Fuku Akutagawa. His mother experienced a mental illness shortly after his birth, so he was adopted and raised by his maternal uncle, Dōshō Akutagawa, from whom he received the Akutagawa family name. He was interested in classical Chinese literature from an early age, as well as in the works of Mori Ōgai and Natsume Sōseki.

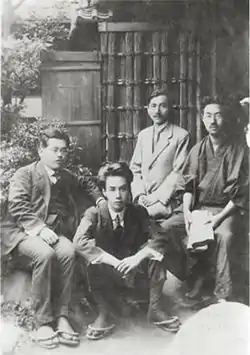

He entered the First High School in 1910, developing relationships with classmates such as Kan Kikuchi, Kume Masao, Yūzō Yamamoto, and Tsuchiya Bunmei, all of whom would later become authors. He began writing after entering Tokyo Imperial University in 1913, where he studied English literature.

While still a student he proposed marriage to a childhood friend, Yayoi Yoshida, but his adoptive family did not approve the union. In 1916 he became engaged to Fumi Tsukamoto, whom he married in 1918. They had three children: Hiroshi Akutagawa (1920–1981) was an actor, Takashi Akutagawa (1922–1945) was killed as a student draftee in Burma, and Yasushi Akutagawa (1925–1989) was a composer.

After graduation, he taught briefly at the Naval Engineering School in Yokosuka, Kanagawa as an English language instructor, before deciding to devote his full efforts to writing.

Literary career

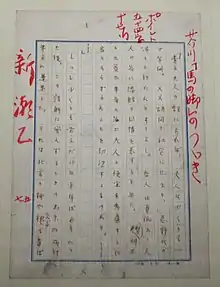

In 1914, Akutagawa and his former high school friends revived the literary journal Shinshichō ("New Currents of Thought"), publishing translations of William Butler Yeats and Anatole France along with their own works. Akutagawa published his second short story Rashōmon the following year in the literary magazine Teikoku Bungaku ("Imperial Literature"), while still a student. The story, based on a twelfth-century tale, was not well received by Akutagawa's friends, who criticized it extensively. Nonetheless, Akutagawa gathered the courage to visit his idol, Natsume Sōseki, in December 1915 for Sōseki's weekly literary circles. In November, he published his short story Rashomon on Teikoku Mongaku, a literary magazine.[2] In early 1916 he published Hana ("The Nose", 1916), which attracted a letter of praise from Sōseki and secured Akutagawa his first taste of fame.[5]

It was also at this time that he started writing haiku under the haigo (or pen-name) Gaki. Akutagawa followed with a series of short stories set in Heian period, Edo period or early Meiji period Japan. These stories reinterpreted classical works and historical incidents. Examples of these stories include: Gesaku zanmai ("A Life Devoted to Gesaku", 1917) and Kareno-shō ("Gleanings from a Withered Field", 1918), Jigoku hen ("Hell Screen", 1918); Hōkyōnin no shi ("The Death of a Christian", 1918), and Butōkai ("The Ball", 1920). Akutagawa was a strong opponent of naturalism. He published Mikan ("Mandarin Oranges", 1919) and Aki ("Autumn", 1920) which have more modern settings.

In 1921, Akutagawa interrupted his writing career to spend four months in China, as a reporter for the Osaka Mainichi Shinbun. The trip was stressful and he suffered from various illnesses, from which his health would never recover. Shortly after his return he published Yabu no naka ("In a Grove", 1922). During the trip, Akutagawa visited numerous cities of southeastern China including Nanjing, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Suzhou. Before his travel, he wrote a short story "The Christ of Nanjing"; concerning the Chinese Christian community; according to his own imagination of Nanjing influenced by Classical Chinese literature.[6]

Influences

Akutagawa's stories were influenced by his belief that the practice of literature should be universal and can bring together western and Japanese cultures. This can be seen in the way that Akutagawa uses existing works from a variety of cultures and time periods and either rewrites the story with modern sensibilities or creates new stories using ideas from multiple sources. Culture and the formation of a cultural identity is also a major theme in several of Akutagawa's works. In these stories, he explores the formation of cultural identity during periods in history where Japan was most open to outside influences. An example of this is his story Hōkyōnin no Shi ("The Martyr", 1918) which is set in the early missionary period.

The portrayal of women in Akutagawa's stories was primarily shaped by the influence of three women who acted as his mother figures; most significantly his biological mother Fuku, from whom he worried about inheriting her mental illness. Although he did not spend much time with Fuku, he identified strongly with her and believed that, if at any moment he might go mad, life was meaningless. His aunt Fuki played the most prominent role in his upbringing, controlling much of Akutagawa's life as well as demanding much of his attention, especially as she grew older. Women that appear in Akutagawa's stories, much like the women he identified as mothers, were mostly written as dominating, aggressive, deceitful, and selfish. Conversely, men were often represented as the victims of such women.

Later life

The final phase of Akutagawa's literary career was marked by his deteriorating physical and mental health. Much of his work during this period is distinctly autobiographical, some even taken directly from his diaries. His works during this period include Daidōji Shinsuke no hansei ("The Early Life of Daidōji Shinsuke", 1925) and Tenkibo ("Death Register", 1926).

Akutagawa had a highly publicized dispute with Jun'ichirō Tanizaki over the importance of structure versus lyricism in story. Akutagawa argued that structure, how the story was told, was more important than the content or plot of the story, whereas Tanizaki argued the opposite.

Akutagawa's final works include Kappa (1927), a satire based on a creature from Japanese folklore, Haguruma ("Spinning Gears", 1927), Aru ahō no isshō ("A Fool's Life"), and Bungeiteki na, amari ni bungeiteki na ("Literary, All Too Literary", 1927).

Towards the end of his life, Akutagawa began suffering from visual hallucinations and anxiety over the fear that he had inherited his mother's mental disorder. In 1927 he survived a suicide attempt, together with a friend of his wife. He later died of suicide after taking an overdose of Veronal, which had been given to him by Saito Mokichi on 24 July of the same year. In his will he wrote that he felt a "vague insecurity" (ぼんやりした不安, bon'yari shita fuan) about the future.[7] He was 35 years old.

Legacy

Akutagawa wrote over 150 short stories during his brief life,[8] a number of which were adapted into other art forms: Akira Kurosawa's classic 1950 film Rashōmon retells Akutagawa's In a Grove, with the title and the frame scenes set in the Rashomon Gate taken from Akutagawa's Rashōmon.[9] Ukrainian composer Victoria Poleva wrote the ballet Gagaku (1994), based on Akutagawa's Hell Screen. Japanese composer Mayako Kubo wrote an opera named Rashomon, based on Akutagawa's story. The German version premiered in Graz, Austria in 1996, and the Japanese version in Tokyo in 2002.

In 1930, writer Tatsuo Hori, who saw himself as a disciple of Akutagawa, published his short story Sei kazoku (lit. "The Holy Family"), which was written under the impression of Akutagawa's death[10] and even paid reference to the dead mentor in the shape of the deceased character Kuki.[11] In 1935, Akutagawa's lifelong friend Kan Kikuchi established the literary award for promising new writers, the Akutagawa Prize, in his honor.

In 2020 NHK produced and aired the film A Stranger in Shanghai. It depicts Akutagawa's time in as a reporter in the city and stars Ryuhei Matsuda.[12]

Selected works

| Year | Japanese title | English title | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | 老年 Rōnen | Old Age | Ryan Choi |

| 1915 | 羅生門 Rashōmon | Rashōmon | Jay Rubin |

| 1916 | 鼻 Hana | The Nose | Jay Rubin |

| 芋粥 Imogayu | Yam Gruel | ||

| 手巾 Hankechi | The Handkerchief | Charles De Wolf | |

| 煙草と悪魔 Tabako to Akuma | Tobacco and the Devil | ||

| 1917 | 尾形了斎覚え書 Ogata Ryosai Oboe gaki | Dr. Ogata Ryosai: Memorandum | |

| 戯作三昧 Gesakuzanmai | Absorbed in writing popular novels | ||

| 首が落ちた話 Kubi ga ochita hanashi | The Story of a Head That Fell Off | 2004, Jay Rubin | |

| 1918 | 蜘蛛の糸 Kumo no Ito | The Spider's Thread | Jay Rubin |

| 地獄変 Jigokuhen | Hell Screen | Jay Rubin | |

| 枯野抄 Kareno shō | A commentary on the desolate field for Bashou | ||

| 邪宗門 Jashūmon | Jashūmon | ||

| 奉教人の死 Hōkyōnin no Shi | The Death of a Disciple | Charles De Wolf | |

| 袈裘と盛遠 Kesa to Morito | Kesa and Morito | Takashi Kojima | |

| 1919 | 魔術 Majutsu | Magic | |

| 竜 Ryū | Dragon: the Old Potter's Tale | Jay Rubin | |

| 1920 | 舞踏会 Butou Kai | A ball | |

| 秋 Aki | Autumn | Charles De Wolf | |

| 南京の基督 Nankin no Kirisuto | Christ in Nanking | ||

| 杜子春 Toshishun | Tu Tze-chun | ||

| アグニの神 Aguni no Kami | God of Aguni | ||

| 1921 | 山鴫 Yama-shigi | A snipe | |

| 秋山図 Shuzanzu | Autumn Mountain | ||

| 上海游記 Shanhai Yūki | A report on the journey of Shanghai | ||

| 1922 | 藪の中 Yabu no Naka | In a Grove, also In a Bamboo Grove | |

| 将軍 Shōgun | The General | ||

| トロッコ Torokko | A Lorry | ||

| 1923 | 保吉の手帳から Yasukichi no Techō kara | From Yasukichi's notebook | |

| 1924 | 一塊の土 Ikkai no Tsuchi | A clod of earth | |

| Writer's Craft | Jay Rubin | ||

| 1925 | 大導寺信輔の半生 Daidōji Shinsuke no Hansei | Daidōji Shinsuke: The Early Years | |

| 侏儒の言葉 Shuju no Kotoba | Aphorisms by a pygmy | ||

| 1926 | 点鬼簿 Tenkibo | Death Register | Jay Rubin |

| 1927 | 玄鶴山房 Genkaku Sanbō | Genkaku Sanbo | |

| 蜃気楼 Shinkiro | A Mirage | ||

| 河童 Kappa | Kappa | ||

| 文芸的な、余りに文芸的な Bungeiteki na, amarini Bungeiteki na | Literary, All-Too-Literary | ||

| 歯車 Haguruma | Spinning Gears also Cogwheels | Jay Rubin; Charles De Wolf | |

| 或阿呆の一生 Aru Ahō no Isshō | Fool's Life also The Life of a Fool | Jay Rubin; Charles De Wolf | |

| 西方の人 Saihō no Hito | The Man of the West | ||

| 或旧友へ送る手記 Aru Kyūyū e Okuru Shuki | A Note to a Certain Old Friend |

Selected works in translation

- Tales of Grotesque and Curious. Trans. Glenn W. Shaw. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press, 1930.

- Tobacco and the devil.--The nose.--The handkerchief.--Rashōmon.--Lice.--The spider's thread.--The wine worm.--The badger.--The ball.--The pipe.--Mōri Sensei.

- "The Christ of Nanking" (Nankyo no Kirisuto). Trans. Ivan Morris. In The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature, Volume 1: From Restoration to Occupation, 1868-1945. New York: Columbia University Press (2005).

- Fool's Life. Trans. Will Peterson Grossman (1970). ISBN 0-670-32350-0

- Kappa. Trans. Geoffrey Bownas. Peter Owen Publishers (2006) ISBN 0-7206-1200-4

- Hell Screen. Trans. H W Norman. Greenwood Press. (1970) ISBN 0-8371-3017-4

- Mandarins. Trans. Charles De Wolf. Archipelago Books (2007) ISBN 0-9778576-0-3

- Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories. Trans. Jay Rubin. Penguin Classics (2004). ISBN 0-14-303984-9

- Travels in China (Shina yuki). Trans. Joshua Fogel. Chinese Studies in History 30, no. 4 (1997).

- TuTze-Chun. Kodansha International (1965). ASIN B0006BMQ7I

- La fille au chapeau rouge. Trans. Lalloz ed. Picquier (1980). in ISBN 978-2-87730-200-5 (French edition)

References

- "Akutagawa Ryunosuke and the Taisho Modernists". aboutjapan.japansociety.org. About Japan. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- 戸部原, 文三 (2015). 一冊で名作がわかる 芥川龍之介(KKロングセラーズ). PHP研究所. ISBN 978-4-8454-0785-9.

- Jewel, Mark. "Japanese Literary Awards" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Retrieved 2014-06-25. - Books: Misanthrope from Japon Monday, Time Magazine. Dec. 29, 1952

- Keene, Donald (1984). Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 558–562. ISBN 978-0-03-062814-6.

- 関口, 安義 (2007). 世界文学としての芥川龍之介. Tokyo: 新日本出版社. p. 223. ISBN 9784406050470.

- "芥川龍之介 或旧友へ送る手記". www.aozora.gr.jp.

- Peace, David (27 March 2018). "There'd be dragons". The Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Arita, Eriko, "Ryunosuke Akutagawa in focus", Japan Times, 18 March 2012, p. 8.

- "堀辰雄 (Hori Tatsuo)". Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- Watanabe, Kakuji (1960). Japanische Meister der Erzählung (in German). Bremen: Walter Dorn Verlag.

- World-Japan, Nhk (2019-12-03). "A Stranger in Shanghai, Dramatic Film that Captures Tumult of 1920's Shanghai, Makes International Broadcast Premiere on NHK WORLD-JAPAN December 27, 28". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

English

- Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West. Columbia University Press; (1998). ISBN 0-231-11435-4

- Ueda, Makoto. Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature. Stanford University Press (1971). ISBN 0-8047-0904-1

- Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories - the Chronology Chapter, Trans. Jay Rubin. Penguin Classics (2007). ISBN 978-0-14-303984-6

Japanese

- Nakada, Masatoshi. Akutagawa Ryunosuke: Shosetsuka to haijin. Kanae Shobo (2000). ISBN 4-907846-03-7

- Shibata, Takaji. Akutagawa Ryunosuke to Eibungaku. Yashio Shuppansha (1993). ISBN 4-89650-091-1

- Takeuchi, Hiroshi. Akutagawa Ryunosuke no keiei goroku. PHP Kenkyujo (1983). ISBN 4-569-21026-0

- Tomoda, Etsuo. Shoki Akutagawa Ryunosuke ron. Kanrin Shobo (1984). ISBN 4-906424-49-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ryūnosuke Akutagawa |

Works related to Ryūnosuke Akutagawa at Wikisource

Works related to Ryūnosuke Akutagawa at Wikisource- Works by Ryunosuke Akutagawa at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ryūnosuke Akutagawa at Internet Archive

- Works by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Short works in English translation (from Asymptote (journal)).

- Short stories in English translation (from The Yale Review).

- Akutagawa Ryunosuke on aozora.gr.jp (complete texts with furigana)

- Akutagawa Ryunosuke on Amazon Kindle Store (Japanese texts with furigana)

- Literary Figures from Kamakura

- Ryunosuke Akutagawa's grave

- Petri Liukkonen. "Ryūnosuke Akutagawa". Books and Writers

- Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories

- J'Lit | Authors : Ryunosuke Akutagawa | Books from Japan (in English)