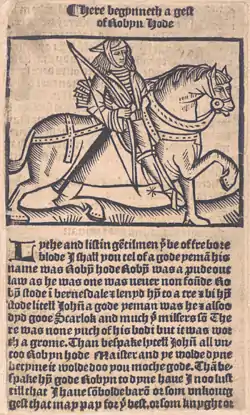

A Gest of Robyn Hode (poem)

A Gest of Robyn Hode (also known as A Lyttell Geste of Robyn Hode, and hereafter referred to as Gest) is one of the earliest surviving texts of the Robin Hood tales. Gest (which meant tale or adventure) is a compilation of various Robin Hood tales, arranged as a sequence of adventures involving the yeoman outlaws Robin Hood and Little John, the poor knight Sir Richard at the Lee, the greedy abbot of St Mary's Abbey, the villainous Sheriff of Nottingham, and King Edward of England.

As a literary work, Gest was first studied in detail by William Hall Clawson in 1909.[1] Research did not resume until 1968, when the medievalist D C Fowler published A Literary History of the Popular Ballad.[2]

Gest as poetry

Written in late Middle English poetic verse, Gest was originally considered an early example of an English language ballad, in which the verses are grouped in quatrains with an abcb rhyme scheme.[3]: ?? However, Douglas Gray, the first J. R. R. Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language at the University of Oxford, considered the Robin Hood and Scottish Border ballads to be poems. He objected to the then-current definitions of a ballad as some ideal form, whose characteristics were distilled from the Child Ballads.[Note 1] When compared to "this notion of a 'pure ballad', the Robin Hood poems seem messy and anormalous", he contended[4]: 9 Therefore, he titled his article The Robin Hood Poems,[4] and not The Robin Hood Ballads.

Gray admitted that the Robin Hood tales, like most popular literature, are sometimes regarded as "sub-literary material", containing formulaic language and a "thin texture", especially "when they are read on the printed page".[4]: 4 Additionally, he argued, that since Child had grouped all the Robin Hood 'ballads' together, some literary studies had "rashly based themselves on all the Robin Hood ballads in the collection"[4]: 9 , instead of discarding those of dubious value. (Maddicott also recognized this issue, and argued that since so little is known about the origins of the ballads from early manuscripts and early printed texts, internal evidence has to be used.[5]: 233 ) Gray further contended that, as oral poetry, each poem should be judged as a performance. He quoted Ruth Finnegan: "This is not a secondary or peripheral matter, but integral to the identity of the poem as actually realized".[4]: 10 In an oral performance, a skillful raconteur can draw his audience in, making them part of his performance. Thus no two oral performances are identical.[4]: 10 Gray points out that one of the characteristics of Gest are scenes with rapid dialogue or conversations, in which the formulaic diction, limited vocabulary, and stereotyped expressions are artfully used to express emotion.[4]: 25 Such scenes lying dully on a page can spring into action when recited by one or two talented minstrels. (See Sung or Recited?.)

The Gest poet

Gest is a compilation of many early Robin Hood tales, either in verse or prose, but most of them now lost.[6]: 25 [7]: 431 [8]: ?? They were woven together into a single narrative poem by an unknown poet (herein called the 'Gest poet'). F C Child, arguing that there was only one poet, described the Gest poet as "a thoroughly congenial spirit."[3]: 49 W H Clawson considered him "to have been exceedingly skillful"[1]: 24 , while J B Bessinger declared him as "original and transitional"[p 43]. Gray thought the weaving to have "been neatly done"[4]: 23 . J C Holt implied that there were two poets: the original poet who compiled the First, Second, and Fourth Fyttes as a single poem; and another less skilled poet who compiled the Third and Fifth Fyttes into the work produced by the original poet.[6]: 22-25 . Others, such as J R Maddicott[5]: 233-234 , [et al.; list them], have considered him as less than adequate. They point to a narrative that is not sequential (it jumps back and forth between the tales); the transitions between tales are not smooth; there are inconsistencies within each tale, and between the tales.

Gest poet's sources

Child was one of the first to recognize that Gest contains ballads from two different traditions: the Barnsdale tradition (found in the First, Second, and Fourth Fyttes), and the Nottingham tradition (found in the Third, Fifth, and Sixth Fyttes).[3]: 51 Clawson then attempted to identify the source ballads.[1]: 125-7 J C Holt considers Clawson work as fundamental to a careful study of Gest, and admits there is no consensus on how many underlying tales were used, or which lines can be considered the work of the Gest poet. In contrast to Clawson, who struggled mightily to connect Gest with existing outlaw ballads, Holt's study indicated that none of the sources have survived, that the tales were not necessarily in verse form, and that the source tales come from several traditions.[6]: 36 Why the Gest poet used these particular tales to construct this epic-length poem is unknown.

- Tale A, Episode 1 (First Fytte)

- The First Fytte begins with a now-lost light-hearted tale about Robin Hood and a poor knight.[9]: lines 65-244 [1]: 24, 125 The original tale was obviously part of a Barnsdale tradition of Robin Hood, based upon the numerious references to local landmarks. When the Knight is accosted in Barnsdale, he mentions that he planned to spend the night in either Blyth or Doncaster[9]: line 108 .

The remainder of the First Fytte[9]: lines 245-324 [1]: 125 is based on a 'Miracle of the Virgin Mary' story. The 'Miracle' was a moral story often told during religious services, and these stories were very popular. They generally concerned the Virgin Mary (or any of the Saints) being invoked as surety for a loan. The most common ending of a Miracle described an actual miracle to repay the loan. There was also a humorous ending where the repayment money is taken from a person in a religious order who in some way represented the Virgin or Saint. In this ending, this person is regarded as the messenger sent by the Virgin or Saint to repay the debt.[1]: 25-38 The First Fytte ends with Robin Hood and his men outfitting the poor knight in a manner befitting a messenger of the Virgin Mary.[9]: lines 303-4

- Tale A, Episode 2 (Second Fytte)

- This Fytte has a darker tone. The first part of the Second Fytte appears to be based on another now-lost tale, where a knight repays his debt to an Abbot with money received from Robin Hood. Parts of the original tale remain, even though they do not fit with the end of the First Fytte. In the original tale, the Knight is away on an overseas military campaign[9]: lines 353-6 , but unexpectedly re-appears[9]: lines 383-4 . He orders his men to put on their ragged travelling clothes before approaching the abbey[9]: lines 385-8 . His men and the horses are led to the stables, as the Knight, also in ragged clothes, enters the great hall[9]: lines 390-404 . Note that Little John is never mentioned, nor is the Abbey named. Near the end of the Fytte, the Knight resumes his good clothing, leaving his ragged clothes at the abbey.[9]: lines 499-500 [1]: 42-5

- The rest of this Fytte appears to be fragments of other tales, perhaps compiled by the Gest poet. The light-hearted fragment describing how the Knight prepares to repay Robin Hood[9]: lines 501-536 has an internal consistency, and is reminiscent of the opening lines of the First Fytte. The fair at Wentbridge[9]: lines 537-568 may have been taken from another tale[1]: 47 to be used as a plot device to delay the Knight, thus preparing for the tale of Robin Hood and the Monk in the Fourth Fytte.

- Tale B, Episode 1 (Third Fytte)

- This episode probably consists of three or four now-lost tales. The light-hearted opening scene at the archery shoot[9]: lines 577-600 could have be borrowed from any of the then-popular tales. After which the Gest poet inserted two quatrains which refer to Little John's courteous master from whom the Sheriff must secure permission.[9]: lines 601-608 The second now-lost tale[9]: lines 613-760 is definitely low comedy. The audience is told that Little John is seeking vengeance on the Sheriff for some unspecified action.[9]: lines 613-616 When Little John is denied breakfast because he slept in, the subsequent action of "exuberant rough-house" "turns into a scene of total destruction"[4]: 28 , as Little John picks a fight with the butler. The tale then assumes "an air of carnival 'justice'"[4]: 28 , when he breaks into the pantry to eat and drink his fill.

- However, the third tale[9]: lines 761-796 has a somber tone, as Little John lures the Sheriff into an ambush. Instead of killing them all, Robin makes the Sheriff and his men endure a night on the cold wet ground, wearing nothing but a green mantle.

- The last few lines of the Fytte[9]: lines 797-816 were probably written by the Gest poet. The Sheriff's complains that he would rather have Robin "smite off mine head"[9]: line 799 than spend another night in the greenwood. Robin then demands the Sheriff swear an oath on Robin's sword not to harm Robin or his men[9]: lines 805-806, 813 . This little scene is a foreshadow of the scene in Tale B, Episode 3 (Sixth Fytte), where Robin Hood uses his sword to decapititate the Sheriff as punishment for breaking his oath[9]: lines 1389-1396 .

- Tale A, Episode 3a (Fourth Fytte)

- The Second Fytte ended with the Knight being delayed at the fair at Wentbridge. The Fourth Fytte opens with Robin Hood worrying about the Knight's late arrival.[9]: lines 821-828 It's not about the money; he is fretting about why the Virgin Mary is upset with him. This is the Gest poet's introduction to yet another now-lost tale about Robin and the Monk.[9]: lines 829-1040 This tale is also the ending of the Miracle story, as Little John recognizes that the Monk carries the debt repayment which was ensured by the Virgin Mary.

At the beginning of the Monk tale, there is another inconsistency. When first spotted by Little John, there were two monks.[9]: line 851 Later, at the feast, there is only one monk mentioned.[9]: lines 897-1040

- Tale A, Episode 3b (Fourth Fytte)

- The last part of the Fytte[9]: lines 1041-1120 is the ending of Tale A. This reunion and reconciliation of Robin and the Knight was most probably original material written by the Gest poet.

- Tale B, Episode 2 (Fifth Fytte)

- The original now-lost tale probably consisted of the archery match, the subsequent attack by the Sheriff's men, the wounding of Little John, and the flight into the greenwood.(lines ) No parallels have been found among the extant contemporary tales. The remainder of the Fytte was composed by the Gest poet.[1]: 80-3

- Tale B, Episode 3 (Sixth Fytte)

- The original now-lost tale probably consisted of the sheriff capturing a gentle knight, taking him to Nottingham, the knight's wife begging Robin to save her husband, the subsequent skirmish, and the rescued knight becoming a fugitive in Robin's group.[9]: lines 1321-1408 Once again, there are no parallels to be found among the extant contemporary tales. The remainder of the Fytte was composed by the Gest poet.[1]: 84-91

- Tale C, Episode 1 (Seventh Fytte)

- Separately from the Robin Hood ballads, Child discussed the "King and Subject" ballad tradition, in which the King (in disguise) meets with one of his Subjects.[Child, V, pt 1] He mentions in passing that the Seventh and Eighth Fyttes of Gest contains such a tale.[p 69] Both Child and Clawson dismiss The King's Disguise, and Friendship with Robin Hood (Child 151), (the only extant Robin Hood ballad involving the king) as being an 18th century paraphrase of Gest. Curiously, both also discuss two tales, King Edward and the Shepherd[Rochester] and The King and the Hermit,[Rochester] as being very similar to the original ballad underlying the Seventh Fytte, but never make the connection.[1]: 106-7, 127 Clawson simply remarks that "tales like this are common and popular the world over".[1]: 103 However, Thomas Ohlgren considers the parallels between the two tales as part of the evidence supporting his assertion that "our comely king" in Gest was Edward III.[8]: 9-12 (See Historical Analysis)

- Tale C, Episode 2 (Eighth Fytte)

- Both Child and Clawson are silent on possible sources for this Fytte.

Narrative arc

The sequence of the tales and episodes in Gest is confusing to most modern readers acccustomed to novels with chronological chapters. Maddicott referred to this confusing sequence as the "disjointed lack of artistic unity" resulting from "a medley of material from various now vanished ballads or tales".[1978_Maddicott, p 233] However, this view does not recognize that the people listening to the tales knew them by heart. Langland and the Scottish chroniclers all remark on the extreme popularity of the RH rhymes(see here). Perhaps the Gest poet purposefully retained what Gray referred to as "loose ends"[4]: 23 — the awkward transitions between episodes, the inconsistencies, the jumping back & forth between tales. Perhaps the Gest poet wanted his audience to recognize the original tales (similar to the old game show Name That Tune), because the he wanted his changes to stand out. According to Clawson, Francis B Gummere coined the phrase "leaping and lingering"[10]: 352 to describe the technique used in many ballads to skip over unimportant events or details in order to dwell on the important ones. The Gest poet leapt from one well-known tale to another in order to dwell on scenes in which he could show who Robin Hood really was. Only the episodes of Tale A are provided here as examples.

- Tale A, Episodes 1, 2, and 3

Character descriptions

Most of the main characters are described in 52 lines at the beginning of the poem.[9]: lines 1-20, 29-60 Thus the Gest poet immediately draws attention to the purpose of his work. Gest's scenes are constructed to show the difference in the behavior of good and wicked characters. Goodness (referred to as "Courtesy") is displayed as ethical or moral qualities, such as kindness, generosity, truthfulness, and personal loyalty. "Courtesy" (the word occurs 17 times in Gest) is the opposite of injustice.[4]: 30

- Robin Hood

- good yeoman

See Historical Analysis section for a fuller description of yeoman as used in Gest.

- proud outlaw

This is the only time 'proud' is applied to Robin Hood; but it is applied to the Sheriff of Nottingham 20 times throughout the Gest. The word is being used in 2 different senses (meanings). When applied to the Sheriff, proud means 'haughty, arrogant'. When applied to Robin, proud means 'brave, bold, valiant', or 'noble in bearing or appearance'.[11]

- courteous outlaw

In Middle English, courtesy meant 'refined, well-mannered, polite' and 'gracious, benevolent, generous, merciful'.[12] Robin repeatedly exhibits all these traits.

- devout

Robin hears three masses a day, and has a special devotion to the Virgin Mary. The latter is a strong motivator for him in Tale A.

- leadership

Robin is able to impose a code of conduct upon his fellow outlaws. He insists that they can do "well enough"[9]: line 50 by not waylaying farmers, yeomen, or any knight or squire who is a "good fellow".[9]: line 55 He singles out bishops and archbishops for beatings. Robin has a particularly strong hostility for the Sheriff of Nottingham.

- Little John

- He defers to Robin by calling him "Master",[9]: lines 19, 41 and serves as Robin's right-hand man. But he is not reluctant in letting Robin know how he feels about following his orders. He agrees to follow Robin's code of conduct for the fellowship, but shows his concern (or irritation) when Robin insists on finding a stranger for dinner so late in the day.

- Much, the miller's son

- Apparently of short stature, Much is praised as every "inch of his body ... worth a man".[9]: lines 15-16 In Tale B, Much saves a wounded Little John by carrying him on his back.

The remaining characters are described when they appear in the tale. Each character is described by one or more of their ethical or moral qualities. There are only three characters who are given a physical description.

- The Sorrowful Knight

- The Gest poet spends eight lines describing his physical appearance.[9]: lines 85-92 Little John, a good judge of people, calls him "gentle", "courteous", & "noble".[9]: lines 95, 98 These qualities the Knight demonstrates repeatedly in Tales A and B.

- The Greedy Abbot and the Kind-hearted Prior

- The qualities of these two characters are revealed during their conversation at dinner, while awaiting the arrival of the Knight.[9]: lines 341-362 The Abbot compounds his wickedness with a lie by calling the Knight "false".[9]: line 455

- The Chief Steward

- He is introduced as "a fat-headed monk",[9]: line 363-4 emphasizing the fat cheeks and neck under his monk's tonsure. Little John calls him "a churl monk";[9]: line 873 insulting the monk twice with a single word. In Middle English it meant a person lacking in courtesy, or a person of low birth.

- Sheriff of Nottingham

- He is the stereotypical wicked villain with no redeeming qualities. He lies when he tells the King that the Knight is a traitor,[9]: lines 1293-1296 but later becomes a traitor himself by breaking his oath to Robin.[9]: lines 1391-1396

- King Edward

- See Historical Analysis section for a fuller description of the character of "our comely King".[9]: line 1412

Notes

- There is an unresolved debate among those who study the history of ballads. Those who favor the position that ballads originated as communal songs and dances are known as communalists; those who support the opposing position that ballads were written by individual authors are known as individualists. (See the Composition section under Ballad.) This debate involved questions that have since been "discarded as subjects for fruitful inquiry" (see Roger D Abrahams' review of Anglo-American Folksong Scholarship since 1898 by D K Wilgus). The current consensus is that, since so little is known about the origins of the earliest ballads, their origins can only be deduced from clues within the texts themselves; that is, on a case-by-case basis. It was advocated by the English historian J R Maddicott in a series of articles in the journal Past & Present (1958-61) and re-iterated in 1978 in his "Birth and Setting of the Ballads of Robin Hood".

Independent support for minstrel origins was offered by historian Maurice Keen in the Introduction to his second edition (1977) of The Outlaws of Medieval Legend. Keen stated that criticism forced him to abandon his original arguments that the ballad form of the Robin Hood stories indicated a primitive popular origin.(p xiii) He now supported the position that the narrative ballads were minstrel compositions. Unfortunately, he never revised the pertinent chapters (XI and XIV) to reflect his new position.

References

- Clawson, William Hall (1909). The gest of Robin Hood (1 ed.). Toronto CA: University of Toronto library. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Fowler, D C, ed. (1968). A Literary History of the Popular Ballad (1 ed.). Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- Child, Francis James, ed. (1888). "117 A GEST OF ROBYN HODE". The English and Scottish popular ballads. Vol. 3, part V (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin. p. 39. Archived from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- Gray, Douglas (1999). "The Robin Hood Poems". In Knight, Stephen (ed.). Robin Hood: An Anthology of Scholarship and Criticism (1 ed.). Cambridge, England: D S Brewer. pp. 3–37. ISBN 0 85991 525 5.

- Maddicott, J R (1999). "Birth and Setting of the Ballads of Robin Hood". In Knight, Stephen (ed.). Robin Hood: An Anthology of Scholarship and Criticism (1 ed.). Cambridge, England: D S Brewer. ISBN 0 85991 525 5.

- Holt, J. C. (1996) [1989]. Robin Hood Revised and enlarged edition. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- Jones, H S V (1910). "Review: The Gest of Robin Hood by W. H. Clawson". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 9 (3): 430–432. JSTOR 27700048. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Ohlgren, Thomas (January 2000). "Edwardus redivivus in a "Gest of Robyn Hode"". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 99 (1): 1–28. JSTOR 27711904. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- "A Gest of Robyn Hode". The Robin Hood Project. University of Rochester. 2021. Archived from the original on 14 Nov 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- Clawson, William Hall (1908). "Ballad and Epic". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 21 (82): 349–361. JSTOR 534582. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Middle English Dictionary". Middle English Compendium. University of Michigan Library. 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- "Middle English Dictionary". Middle English Compendium. University of Michigan Library. 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.