1953 in spaceflight

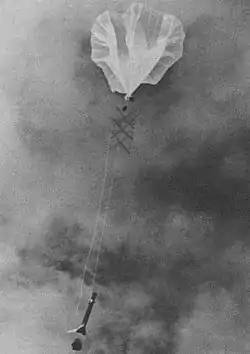

The year 1953 saw the rockoon join the stable of sounding rockets capable of reaching beyond the 100 kilometres (62 mi) boundary of space (as defined by the World Air Sports Federation).[1] Employed by both the University of Iowa and the Naval Research Laboratory, 22 total were launched from the decks of the USS Staten Island and the USCGC Eastwind this year. All branches of the United States military continued their program of Aerobee sounding rocket launches, a total of 23 were launched throughout 1953. The Soviet Union launched no sounding rockets in 1953; however, the Soviet Union did conduct several series of missile test launches.

| |

| Rockets | |

|---|---|

| Maiden flights | |

| Retirements | |

Both the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics continued their development of ballistic missiles: the United States Air Force with its Atlas ICBM, the United States Army with its Redstone SRBM, the Soviet OKB-1 with its R-5 IRBM, and Soviet Factory 586 with its R-12 IRBM. None entered active service during 1953.

The first meeting of the Comité Speciale de l'Année Géophysique Internationale (CSAGI), a special committee of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), began preliminary coordination of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), scheduled for 1957–58.

Space exploration highlights

US Navy

On 25 May 1953, Viking 10, originally planned to be the last of the Naval Research Laboratory-built Viking rockets, arrived at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. A successful static firing on 18 June cleared the way for a 30 June launch date, a schedule that had been made months prior, before the rocket had even left the Glenn L. Martin Company plant where it had been built. At the moment of liftoff, the tail of Viking 10 exploded, setting the rocket afire. Water was immediately flooded into the rocket's base in an attempt to extinguish the fire, but flames continued to burn in the East Quadrant of the firing platform. Half an hour after launch, two of the launch team under manager Milton Rosen were dispatched to put out the fire to salvage what remained of the rocket.

Though successful, these efforts were then threatened by a slow leak in the propellant tank. The vacuum created by the departing fuel was causing the tank to dimple with the danger of implosion that would cause the rocket to collapse. Lieutenant Joseph Pitts, a member of the launch team, shot a rifle round into the tank, equalizing the pressure and saving the rocket. Three hours after the attempted launch, the last of the alcohol propellant had been drained from Viking 10. The launch team was able to salvage the instrument package of cameras, including X-ray detectors, cosmic ray emulsions, and a radio-frequency mass-spectrometer, valued at tens of thousands of dollars, although there was concern that the rocket was irreparable.

A thorough investigation of the explosion began in July, but a conclusive cause could not be determined. In a reported presented in September, Milton Rosen noted that a similar occurrence had not happened in more than 100 prior tests of the Viking motor. It was decided to rebuild Viking 10, and a program for closer monitoring of potential fail points was implemented for the next launch, scheduled for 1954.[2]

American civilian efforts

After the successful field tests of balloon-launched rockets (rockoons) the previous year, a University of Iowa physics team embarked on a second rockoon expedition aboard the USS Staten Island in summer 1953 with improved equipment. The new Skyhook balloons increased the rocket firing altitude from 40,000 feet (12,000 m) to 50,000 feet (15,000 m) affording a peak rocket altitude of 57 miles (92 km). The total payload weights were increased by 2 pounds (0.91 kg) to 30 pounds (14 kg). Between 18 July and 4 September, the Iowa team launched 16 rockoons from a variety of latitudes, 7 of which reached useful altitudes and returned usable data. An NRL team aboard the same vessel launched six rockoons, of which half were complete successes. Data from these launches provided the first evidence of radiation associated with aurora borealis.[3]

Spacecraft development

US Air Force

Development of the Atlas, the nation's first ICBM proceeded slowly throughout 1953. Without firm figures as to the weight and dimension of a thermonuclear device (the US tested its first H-bomb in November 1952, the USSR announced their first successful test in August 1953), it was not known if the Atlas could deliver an atomic bomb payload.

In spring 1953, Colonel Bernard Schriever, an assistant in development planning at The Pentagon and a proponent of long-ranged ballistic missiles, pushed to obtain accurate characteristics of a nuclear payload. Trevor Gardner, special assistant for research and development to the new Secretary of the Air Force, Harold Talbott, responded by organizing the Strategic Missiles Evaluation Committee or "Teapot Committee" comprising eleven of the top scientists and engineers in the country. Their goal would be to determine if a nuclear payload could be made small enough to fit on the Atlas rocket. If so, the importance of the committee's members would allow such findings to accelerate Atlas development. By October, committee member John von Neumann had completed his report on weights and figures indicating that smaller, more powerful warheads within Atlas' launch capability would soon be available. Pending test verification of von Neumann's theoretical results, the Air Force began revising the Atlas design for the projected nuclear payload.[4]

US Army

The first production Redstone, a surface-to-surface missile capable of delivering nuclear or conventional warheads to a range of 200 miles (320 km), was delivered on 27 July 1953. A Redstone R&D missile was flight tested on 20 August 1953.[5]

Soviet Union

The R-5 missile, able to carry the same 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) payload as the R-1 and R-2 but over a distance of 1,200 kilometres (750 mi)[6]: 242 underwent its first series of eight test launches from 15 March to 23 May 1953. After two failures, the third rocket, launched 2 April, marked the beginning of streak of success. Seven more missiles were launched between 30 October and December, all of which reached their targets. A final series of launches, designed to test modifications made in response to issues with the first series, was scheduled for mid-1954.[7]: 100–101

In his brief tenure as Director of NII-88, responsible for the production of all Soviet ballistic missiles, engineer Mikhail Yangel chafed professionally with OKB-1 (formerly NII-88 Section 3) Chief Designer, Sergei Korolev, whom he had previously reported to as Deputy Chief Designer of the bureau. To relieve this tension, on 4 October 1953, Yangel was demoted to NII-88 Chief Engineer and assigned responsibility for production of missiles at State Union Plant No. 586 in Dnepropetrovsk. This plant under, Vasiliy Budnik, had been tasked on 13 February 1953 with developing the R-12 missile, possessing a performance similar to that of the R-5 (range of 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) vs. 1,200 kilometres (750 mi)) but using storable propellants so that it could be stored at firing readiness for extended periods of time.[7]: 113–114

At the end of 1953, at a meeting of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, it was determined that a transportable thermonuclear device be developed (as opposed to the one detonated in August, which was stationary). It as further determined that an ICBM be developed to carry said bomb. As no ICBMs existed at the time, in reality or even in planning, development of a nuclear capable R-5 (dubbed the "R-5M") was ordered.[6]: 275

The International Geophysical Year

July 1953 saw the first meeting of the Comité Speciale de l'Année Géophysique Internationale (CSAGI), a special committee of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) tasked with coordinating the International Geophysical Year (IGY), set for 1957–58. This international effort would undertake simultaneous observations of geophysical phenomena over the entire surface of the Earth including such farflung regions as the Arctic and Antarctica. At its first meeting, CSAGI invited the world's nations to participate in the IGY. Response from most prominent nations was quick. The National Research Council of the US National Academy of Sciences set up a US National Committee for the IGY, with Joseph Kaplan serving as chairman and Hugh Odishaw as executive director. The only key nation slow in committing to the IGY was Soviet Union, which did not signal its involvement until spring 1955.[3]: 69–70

Launches

February

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 10 February 21:09 |

|||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Mass spectrometry | 10 February | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 137 kilometres (85 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 12 February 07:09 |

|||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Mass spectrometry | 12 February | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 137.3 kilometres (85.3 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 18 February 06:50 |

|||||||

| USASC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 18 February | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 106.2 kilometres (66.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 18 February 17:42 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Rocket performance test | 18 February | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 117.5 kilometres (73.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

March

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 1 March | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 March | Successful[9] | |||

| 5 March | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 5 March | Successful[9] | |||

| 15 March | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 15 March | Partial failure [7] | |||

| Maiden flight of R-5[10] | |||||||

| 18 March | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 18 March | Partial failure [10][7] | |||

| 19 March | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 19 March | Successful[9] | |||

April

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 2 April | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 2 April | Successful | |||

| First successful R-5 launch[10] | |||||||

| 8 April | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 8 April | Partial failure[10] | |||

| 14 April 15:47 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Rocket performance test | 14 April | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 122.3 kilometres (76.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 19 April | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 19 April | Successful[10] | |||

| 23 April 19:33 |

|||||||

| USASC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 23 April | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 124 kilometres (77 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 24 April 10:19 |

|||||||

| USASC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 24 April | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 107.8 kilometres (67.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 24 April | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 24 April | Partial failure[10] | |||

May

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 11 May | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 11 May | Successful[9] | |||

| 13 May | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 13 May | Successful[10] | |||

| 20 May 14:04 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 20 May | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 114.3 kilometres (71.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 21 May 15:47 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 21 May | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 114.3 kilometres (71.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 23 May | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 23 May | Successful | |||

| Contained 4 supplementary combat compartments; end of 1st set of experimental launches[10] | |||||||

June

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 26 June 19:10 |

|||||||

| ARDC / University of Utah | Suborbital | Ionospheric | 26 June | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 135.2 kilometres (84.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 30 June | |||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 30 June | Launch Failure | |||

| Apogee: 0 kilometres (0 mi), tail exploded on launch pad; rocket rebuilt and launched successfully on 7 May 1954 | |||||||

July

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 1 July 17:52 |

|||||||

| ARDC / University of Utah | Suborbital | Ionospheric | 1 July | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 138.4 kilometres (86.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 6 July | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 6 July | Successful[9] | |||

| 14 July 15:30 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Solar UV | 14 July | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 103 kilometres (64 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 18 July 22:27 |

SUI 8 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 18 July | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 19 July 10:30 |

SUI 9 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 19 July | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 19 July 15:53 |

SUI 10 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 19 July | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 19 July 21:57 |

SUI 11 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 19 July | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 23 July 09:47 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 23 July | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 95.6 kilometres (59.4 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 24 July 16:40 |

SUI 12 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 24 July | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 28 July 09:41 |

SUI 13 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 28 July | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 90 kilometres (56 mi)[11] | |||||||

August

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 3 August 18:28 |

SUI 14 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 3 August | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 5 August 21:54 |

NRL Rockoon 1 | ||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 5 August | ||||

| Apogee: 80 kilometres (50 mi);[11] first of six 1953 NRL flights, three of which reached altitude and returned data[3] | |||||||

| 6 August 15:07 |

SUI 15 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 6 August | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 6 August 18:40 |

SUI 16 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 6 August | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 96 kilometres (60 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 8 August 15:09 |

NRL Rockoon 2 | ||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 8 August | ||||

| Apogee: 80 kilometres (50 mi);[11] second of six 1953 NRL flights, three of which reached altitude and returned data[3] | |||||||

| 9 August 05:54 |

SUI 17 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 9 August | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 100 kilometres (62 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 9 August 19:15 |

NRL Rockoon 3 | ||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 9 August | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 38 kilometres (24 mi);[11] third of six 1953 NRL flights, three of which reached altitude and returned data[3] | |||||||

| 11 August 17:09 |

NRL Rockoon 4 | ||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 11 August | ||||

| Apogee: 80 kilometres (50 mi);[11] fourth of six 1953 NRL flights, three of which reached altitude and returned data[3] | |||||||

| 30 August 14:00 |

SUI 18 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 30 August | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 30 August 16:20 |

SUI 19 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 30 August | Launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 11 kilometres (6.8 mi)[11] | |||||||

| 30 August 20:46 |

SUI 20 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 30 August | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 100 kilometres (62 mi)[11] | |||||||

September

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 1 September 05:05 |

|||||||

| USASC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 1 September | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 107.8 kilometres (67.0 mi), final flight of the Aerobee XASR-SC-2[8] | |||||||

| 3 September 09:50 |

SUI 21 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 3 September | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 90 kilometres (56 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 3 September 11:51 |

SUI 22 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 3 September | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 100 kilometres (62 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 3 September 14:05 |

SUI 23 | ||||||

| University of Iowa | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Ionospheric | 3 September | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 100 kilometres (62 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 4 September 03:59 |

NRL Rockoon 5 | ||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 4 September | ||||

| Apogee: 70 kilometres (43 mi);[11] fifth of six 1953 NRL flights, three of which reached altitude and returned data[3] | |||||||

| 4 September 15:51 |

NRL Rockoon 6 | ||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 4 September | ||||

| Apogee: 70 kilometres (43 mi);[11] sixth of six 1953 NRL flights, three of which reached altitude and returned data[3] | |||||||

| 5 September 05:36 |

|||||||

| USASC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 5 September | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 105.5 kilometres (65.6 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 15 September 15:02 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 15 September | Partial launch failure | |||

| Apogee: 32.2 kilometres (20.0 mi) (Early cut-off due to a thrust chamber burn-through; subsequent shots incorporated improved chamber cooling)[8] | |||||||

| 29 September 20:05 |

|||||||

| USASC | Suborbital | Aeronomy | 29 September | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 58 kilometres (36 mi)[8] | |||||||

October

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 1 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 October | Successful[12] | |||

| 1 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 October | Successful[12] | |||

| 1 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 October | Successful[13] | |||

| 1 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 October | Successful[13] | |||

| 7 October 17:00 |

|||||||

| ARDC | Suborbital | Solar | 7 October | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 99.8 kilometres (62.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 10 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 10 October | Successful[13] | |||

| 16 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 16 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 17 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 17 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 19 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 19 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 20 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 20 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 24 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 24 October | Successful[13] | |||

| 26 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 26 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 27 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 27 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 28 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 28 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 28 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 28 October | Successful[9] | |||

| 30 October | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 30 October | Successful | |||

| Beginning of 2nd stage of experimental launches[10] | |||||||

November

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 1 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 November | Successful[12] | |||

| 1 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 November | Successful[12] | |||

| 1 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 November | Successful[12] | |||

| 1 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 1 November | Successful[12] | |||

| 2 November 18:32 |

|||||||

| ARDC / University of Utah | Suborbital | Ionospheric | 2 November | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 120.7 kilometres (75.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 3 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 3 November | Successful[10] | |||

| 3 November 18:15 |

|||||||

| ARDC / University of Utah | Suborbital | Ionospheric | 3 November | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 121.5 kilometres (75.5 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 12 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 12 November | Successful[9] | |||

| 15 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 15 November | Successful[12] | |||

| 15 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 15 November | Successful[9] | |||

| 17 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 17 November | Successful[10] | |||

| 19 November 22:40 |

|||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Solar | 19 November | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 112.6 kilometres (70.0 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 21 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 21 November | Successful[10] | |||

| 24 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 24 November | Successful[9] | |||

| 25 November 15:46 |

|||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Solar | 25 November | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 95.1 kilometres (59.1 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 26 November | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 26 November | Partial failure[10] | |||

December

| Date and time (UTC) | Rocket | Flight number | Launch site | LSP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payload | Operator | Orbit | Function | Decay (UTC) | Outcome | ||

| Remarks | |||||||

| 1 December 15:30 |

|||||||

| NRL | Suborbital | Aeronomy / Solar | 1 December | Successful | |||

| Apogee: 129.6 kilometres (80.5 mi)[8] | |||||||

| 5 December | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 5 December | Successful[10] | |||

| 9 December | |||||||

| OKB-1 | Suborbital | Missile test | 9 December | Successful | |||

| End of second experimental flight series[10] | |||||||

Suborbital launch summary

By country

| Country | Launches | Successes | Failures | Partial failures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | 32 | 13 | 1 | ||

| 42 | 37 | 0 | 5 | ||

By rocket

| Rocket | Country | Launches | Successes | Failures | Partial failures |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viking (second model) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Aerobee RTV-N-10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Aerobee XASR-SC-1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Aerobee XASR-SC-2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Retired | |

| Aerobee RTV-A-1a | 13 | 12 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Deacon rockoon (SUI) | 16 | 7 | 9 | 0 | ||

| Deacon rockoon (NRL) | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| R-1 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R-2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R-5 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 5 | Maiden flight |

See also

References

- Bergin, Chris. "NASASpaceFlight.com".

- Clark, Stephen. "Spaceflight Now".

- Kelso, T.S. "Satellite Catalog (SATCAT)". CelesTrak.

- Krebs, Gunter. "Chronology of Space Launches".

- Kyle, Ed. "Space Launch Report".

- McDowell, Jonathan. "Jonathan's Space Report".

- Pietrobon, Steven. "Steven Pietrobon's Space Archive".

- Wade, Mark. "Encyclopedia Astronautica".

- Webb, Brian. "Southwest Space Archive".

- Zak, Anatoly. "Russian Space Web".

- "ISS Calendar". Spaceflight 101.

- "NSSDCA Master Catalog". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

- "Space Calendar". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- "Space Information Center". JAXA.

- "Хроника освоения космоса" [Chronicle of space exploration]. CosmoWorld (in Russian).

Footnotes

- Voosen, Paul (24 July 2018). "Outer space may have just gotten a bit closer". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau8822. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Milton W. Rosen (1955). The Viking Rocket Story. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 204–221. OCLC 317524549.

- George Ludwig (2011). Opening Space Research. Washington D.C.: geopress. pp. 18–32. OCLC 845256256.

- John L. Chapman (1960). Atlas The Story of a Missile. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 71–73. OCLC 492591218.

- "Installation History 1953 – 1955". U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Life Cycle Management Command. 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Boris Chertok (June 2006). Rockets and People, Volume II: Creating a Rocket Industry. Washington D.C.: NASA. OCLC 946818748.

- Asif A. Siddiqi. Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974 (PDF). Washington D.C.: NASA. OCLC 1001823253.

- Wade, Mark. "Aerobee". Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Wade, Mark. "R-1 8A11". Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Asif Siddiqi (2021). "R-5 Launches 1953-1959". Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- Wade, Mark. "Deacon Rockoon". Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- Wade, Mark. "R-1". Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Wade, Mark. "R-2". Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2021.