Hōei eruption

The Hōei eruption of Mount Fuji started on December 16, 1707 (23rd day of the 11th month of the year Hōei 4) and ended February 24, 1708. It was the last confirmed eruption of Mount Fuji, with three unconfirmed eruptions being reported from 1708 to 1854.[2] It is well known for the immense ash-fall it produced over eastern Japan, and subsequent landslides and starvation across the country. Hokusai's One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji includes an image of the small crater at a secondary eruption site on the southwestern slope. The area where the eruption occurred is called Mount Hōei because it occurred in the fourth year of Hōei era.[3] Today, the crater of the main eruption can be visited from the Fujinomiya or Gotemba Trails on Mount Fuji.

| Hōei eruption | |

|---|---|

Map of volcanic ash fall during the Hoei eruption | |

| Volcano | Mount Fuji |

| Start date | December 16, 1707[1] |

| End date | February 24, 1708[1] |

| Type | Plinian eruption |

| Location | Chūbu region, Honshu, Japan 35.3580°N 138.7310°E |

| VEI | 5[1] |

Extent of eruption

Three years prior to eruption, rumbling began in 1704 from February 4 to February 7. One to two months prior to the eruption earthquakes could be felt around the base of the volcano, with magnitudes reaching as high as 5.[4] The event was characterized as a plinian eruption, with pumice, scoria, and ash being shot into the stratosphere and raining down far east of the volcano. Landslides soon followed the eruption due to heavy rainfall and flooding in the area.

The eruption happened on Mount Fuji's east–northeast flank and formed three new volcanic vents, named No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 Hōei vents. The catastrophe developed over the course of several days; an initial earthquake and explosion of cinders and ash was followed some days later with the more forceful ejections of rocks and stones.[3] The Hōei eruption is said to have caused the worst ash-fall disaster in Japanese history.[5]

Although it brought no lava flow, the Hōei eruption released some 800 million cubic metres (28×109 cu ft) of volcanic ash, which spread over vast areas around the volcano, even reaching Edo almost 100 kilometres (60 mi) away. Cinders and ash fell like rain in Izu, Kai, Sagami, and Musashi provinces, and ash fall was recorded in Tokyo and Yokohama to the east of the volcano.[6][7] In Edo, the volcanic ash was several centimeters thick.[8] Ash that was released from the eruption fell to the earth and covered many crops in the area, stunting growth. There is no estimate for how many deaths were a result of the eruption. The eruption is rated a 5 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.[2]

Effect on local communities

The Hōei eruption, from 1707–1708 had a disastrous effect on the people living in the Fuji region. The tephra released from the volcano caused an agricultural decline, leading to many in the Fuji area to starve to death.[9]

Volcanic ash fell and widely covered the cultivated fields east of Mount Fuji. To recover the fields farmers cast volcanic products out to dumping-grounds making piles. The rain washed material from the dumping grounds away to the rivers and made some of the rivers shallower, especially into the Sakawa River, into which huge volumes of ash fell, resulting in temporary dams. Heavy rainfall on 7–8 August 1708, the year following the Hōei eruption, caused an avalanche of volcanic ash and mud, breaking the dams and flooding the Ashigara plain.[10]

Many of the casualties caused by the Hoei eruption were due to flooding, landslides, and starvation after the fact. As ash fell after the eruption, crops began to fail, leading to mass amounts of starvation in the Edo (renamed Tokyo in 1869) area.[11] Due to debris that included large rocks, floodwater, and ash, people could also not move easily to other places, which lead to further starvation in the Edo area.[12]

Tectonic setting and the threat for more eruptions

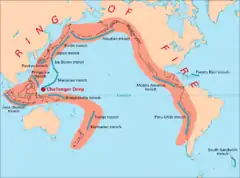

Japan is located in the most geologically active region of Earth, called The Ring of Fire. This region is known for its many volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. The Hōei eruption was preceded by a massive magnitude 8.6 earthquake, just 49 days before the eruption.[13] Many volcanologists believe that this earthquake was likely the cause of the eruption.[14]

Based on the internal pressure inside the volcano that scientists have recently measured, speculation of a possible eruption is high. Damage is estimated to cost Japan over US$25 billion.[15] It is assumed that, much like the 1707 Hōei eruption, the volcano would almost certainly erupt if there was another earthquake such as the 1707 Hōei earthquake. A repeat of the 1707 Hōei eruption is also said to impact over 30 million people in the highly populated areas of eastern Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba and parts of Yamanashi, Saitama, and Shizuoka.[16] The volcano would most heavily affect Tokyo, and would likely cause power outages, water shortages, and malfunctions in the highly technical city.[17]

References

- "Fujisan". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- "Fuji — Eruption History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Smith, Henry (1988). Hokusai: One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. p. 197.

- Chesley, C. J.; La Femina, P. C.; Puskas, C. M.; Kobayashi, D. (2012-12-01). "The 1707 M8.7 Hoei Earthquake Triggered the Largest Historical Eruption of Mt. Fuji". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2012: NH11A–1547. Bibcode:2012AGUFMNH11A1547C.

- Miyaji, Naomichi; Kan'no, Ayumi; Kanamaru, Tatsuo; Mannen, Kazutaka (2011-10-15). "High-resolution reconstruction of the Hoei eruption (AD 1707) of Fuji volcano, Japan". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 207 (3): 113–129. Bibcode:2011JVGR..207..113M. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.06.013. ISSN 0377-0273.

- Miyaji, Naomichi & Kan'no, Ayumi & Kanamaru, Tatsuo & Mannen, Kazutaka. (2011). High-resolution reconstruction of the Hoei eruption (AD 1707) of Fuji volcano, Japan. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 207. 113–129. 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.06.013.

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 416.

- Archived March 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Most Recent Eruption of Mount Fuji". National Geographic Society. 2020-07-21. Retrieved 2021-10-15.

- "A Premodern History of the Odowara". Zombie Zodiac. November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- T., Kaneko. "Fujisan" (PDF). Fujisan.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Myiaji, Naomichi (January 2002). "The 1707 Eruption of Fuji Volcano and Its Tephra". ResearchGate.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Mt Fuji volcano eruptions – eruptive history, info / VolcanoDiscovery". www.volcanodiscovery.com. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- Society, National Geographic (2020-07-21). "Most Recent Eruption of Mount Fuji". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- Blackstone, Samuel. "Experts Predict Japan's Mount Fuji Will Erupt Soon". Business Insider. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- Review, Asia Insurance. "Volcanoes: Modelling the Unimaginable: The risk of catastrophic volcanic eruption". Asia Insurance Review. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- Osaki, Tomohiro (2020-01-03). "After 300 years, is majestic Mount Fuji 'on standby' for next eruption?". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

External links

- 富士山火山防災協議会 (Council for Fuji volcano disaster reduction)

- 富士山宝永噴火(1707)後の土砂災害(PDF) (Distribution of sediment disasters after the 1707 Hoei eruption of Fuji Volcano in central Japan, based on historical documents)